45 Stories in Jewelry: 1947 to Now

February 13, 2020–April 10, 2022

Museum of Arts and Design, New York City, NY, US

The Museum of Arts and Design in New York City has organized an exhibition featuring 105 works from their permanent jewelry collection of over 950 pieces. Curated thematically, the showcases are designed to tell “45 stories” that illustrate significant developments in the studio jewelry movement from 1947 to the present. The exhibition traces the growth of international contemporary jewelry by focusing on select artists, each a pioneer in the field because of their innovative approach, concepts, and/or techniques. Each showcase, within which the jewelry is presented, stands in for one of the 45 permanent visual storage drawers that will ultimately house each presentation. Accompanying the exhibition is a companion book, titled Jewelry Stories: Highlights from the Permanent Collection 1947–2019. Edited by curator Barbara Paris Gifford, it delves into the stories with illuminating texts, as well as scintillating images.

What follows is a dialogue between the two Pratt students who co-authored this review, their musings about the exhibition interspersed with context of the history and foundation of the international studio jewelry movement, formatted in boldface type.

Abigail Ellen Pontefract: Let’s think about how the curators chose to install the exhibition. It’s important to mention that the drawers symbolize the stories being told by each artist. Drawers are where we keep our personal belongings, too. I imagine the curators are trying to shine a spotlight on the more intimate and deeper opinions and stories, which belong to the artists, through their work in studio jewelry. From any artist’s or designer’s point of view, a sketchbook is also a very personal form of storage. Within some of the showcases you can see photos of the creators and their work being modeled, and/or their initial sketches. I think this could relate back to the idea of personal opinions being brought out of the drawers.

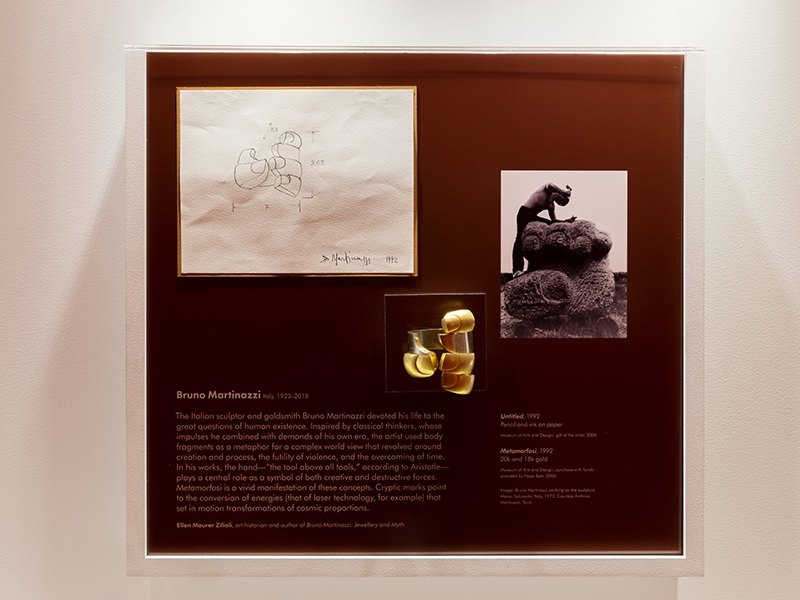

Alexandra Moreno: Yes, for example, in Bruno Martinazzi’s “drawer” the curators included one of his preliminary sketches for the bracelet Metamorfosi, together with a photo of him working on a sculpture outdoors in Italy. (Both display the recurring motif of a hand). In another, Charles Loloma’s bracelet has a mirror placed beneath the piece so viewers can see the underside.

Abigail Ellen: It’s a clever way to show not only the back of a piece, but some hidden techniques. Loloma’s bracelet has turquoise stones inlaid on the inside of the cuff to create a secret connection between him, as the maker, and the wearer.

Alexandra: Another revealing aspect of each “drawer” is the enclosed text written by a specialist or someone particularly knowledgeable about the artist or movement in question. This gives us more information about why this artist and their work is an important part of the development of the studio jewelry movement. The “drawers,” in essence, function as snapshots of the history and evolution of the field.

Abigail Ellen: Most exhibitions have a strict beginning and end, usually to elucidate the premise. 45 Stories in Jewelry goes against this norm. It presents the work in a thematic order. I found myself beginning in the middle of the room and moving back and forth between the different thematic strategies of the exhibition.

Alexandra: One of the strengths of the exhibition is its fluidity, reinforced by video interviews with four of the participating artists—Joyce Scott, Otto Künzli, Bruno Martinazzi, and Ramona Solberg—playing continuously.

Alexandra: Two works stand out from the structure of the exhibition: Lauren Kalman’s video, Tongue Gilding (the only non-physical jewelry included in the exhibition), and Arline Fisch’s Body Ornament (a large body piece presented on an armature, as if it were being worn on a body). I believe this underlines the fact that jewelry artists have, throughout the development of the field and still today, expanded the boundaries of what jewelry is and can be. Some believe jewelry must be worn, while others explore the opposite—jewelry as an autonomous object.

The companion book explains that the two large oval structures forming the exhibition echo the ellipse in the Tiffany Jewelry Gallery, as well as mimicking a communal dining table, framing personal and professional relationships formed within the jewelry field. There are reminders of this throughout the exhibition.

The friendship between Art Smith and Joyce Scott exemplifies this. They met about 50 years ago at Haystack Mountain School of Crafts, in Deer Isle, ME. As one of the first African American studio jewelers to open a shop in Greenwich Village, Smith played a huge role in the history and development of the art and design community. Scott expresses this in her caption for his “drawer.” Scott is represented in the exhibition by one of her more political neckpieces, Voices. It’s the first work one sees coming up the stairs, at the entrance to the show.

Otto Künzli and his former student, David Bielander (both originally from Switzerland), communicate their relationship in jewelry by sharing a “drawer.” The primary theme explored in this case is the question of value. Bielander’s work imitates corrugated cardboard and steel staples by using yellow and white gold, respectively, to create his trompe-l’oeil “cardboard” crown.

Künzli has spent a large part of his practice questioning the value and meaning of gold as well. Gold Macht Blind (Gold Makes You Blind), a black rubber bangle with a gold ball hidden inside, challenges the perception of value as “it was time for gold to return to the darkness.” Künzli’s intention, with the unlimited-edition piece, was to question the attitude toward value if the most valuable part is not visible.

Alexandra: Greenwich Village was the hub for studio jewelry in New York City, beginning in the 1940s with the icons Art Smith and Sam Kramer, among others. You and I are in NYC as students from Europe, learning about the history of the jewelry field here, so it has been enlightening to walk around the formative areas and then see the actual works in this exhibition.

Abigail Ellen: Greenwich Village was a mecca for jewelers as well as other artists. It was also the East Coast locus of the Beat Generation. This made it the perfect place for Kramer to sell his work, as the area was so full of life.

Kramer was phenomenal at marketing. Aware that his audience consisted mostly of the bohemian avant-garde, he promoted his work as “Fantastic Jewelry for People Who Are Slightly Mad.” People bought his jewelry to be part of a “tribe.” It was politically progressive and celebrated the hand of the artist, rather than the value of the materials. Kramer delighted in playing mind games with prospective buyers. This sometimes took the form of public performances, such as sending models adorned in his jewelry—and otherwise costumed as “Space Girls”—around Greenwich Village on mopeds, handing out flyers advertising his shop.

Abigail Ellen: Kramer and contemporary German jeweler Karl Fritsch share a “drawer” in the show. It may seem unexpected. However, both were labeled as radicals and renegades in the jewelry world. The two aimed to have their work provoke in a surrealist fashion. In that way, they’re in sync. Kramer and Fritsch also shared the intention to make us think about what a jewel could really be, conceptually and technically.

Alexandra: Kramer’s “Space Girls” and futuristic theme reminds me of Gijjs Bakker and Emmy van Leersum, who were also working in the outer space context, but two decades later, and in Europe. They presented their work like a fashion show, with women wearing spandex suits and futuristic jewelry.

Frequent subjects in the studio jewelry field, such as politics and the use of common materials and found objects, are represented in 45 Stories in Jewelry, too. The exhibition displays pieces created during anti-Vietnam War protests. At the time, J. Fred Woell made his pendant The Good Guys, which is included in the show. The piece mimics religious icons but with cartoon characters standing in for the Holy Trinity. He was questioning mainstream American values and also helping lead jewelry in an innovative direction. After pinning a nail to a shoe, J. Fred Woell had had a realization. He ditched his Scandinavian aesthetic and used found objects in his practice instead.

This technique of working with readymades has continued to influence artists who came later, giving objects a new purpose and alternative meanings. MJ Tyson, a contemporary jeweler likewise featured in the show, is expanding the subject of found object jewelry today. But unlike Woell, she follows a nostalgic path, merging childhood and household items by casting them into jewelry that blurs the lines between materiality and personal value.

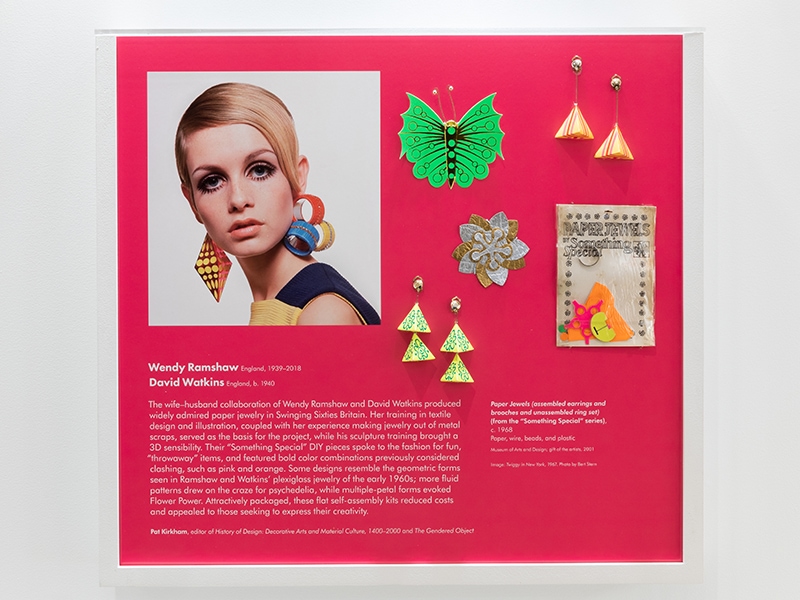

Abigail Ellen: Although studio jewelry in the US really took off after World War II, there was considerable experimentation with plastics, aluminum, and paper during the war years, as these materials were readily available and compensated somewhat for the shortage of metal. Even after the war contemporary jewelers have continued to experiment with these mass-produced materials, along with other common ones. Wendy Ramshaw and David Watkins created a collection of plastic jewelry, followed by their Something Special DIY paper jewelry line (featured in the 45 Stories show), which was popular in the late 1960s.

Alexandra: Also due to World War II, many Europeans—particularly Germans— came to the US to escape the Nazis. The US didn’t have European-style apprenticeships and hadn’t offered many opportunities to learn jewelry-making. Many budding jewelers were self-taught. Upon coming to the US, European artists started to teach at arts and crafts institutions. This really expanded the field, and can be seen in some of the jewelry that was made during this time.

Abigail Ellen: Yes, Margaret De Patta’s work was made following her studies with Hungarian Constructivist Lázló Moholy-Nagy at his School of Design, in Chicago. Moholy-Nagy, who had been a professor at the Bauhaus, in Germany, passed on his aesthetic to De Patta. She adapted his innovative uses of visual effects, such as light, image reflection, and magnification for her work, achieving it through screening techniques of the crystals and eccentrically cut stones. She played with shape, structure, and optical illusion. Her pendant made from rock crystal and diamonds, featured in 45 Stories, exemplifies this.

As one leaves the space, it’s clear that it is not the complete story of studio jewelry. When the exhibition closes, the drawers will be put back into their dedicated space on the second floor of the museum, allowing them to live on and let future visitors discover the ever-growing collection. It leaves one wondering about the future and what responsibilities current jewelry artists might have in doing their part to fill these gaps. The storytelling will continue with innovators finding new concepts, techniques, and relationships, guided by jewelers of the past.

Note: This exhibition was accompanied by a catalog. The exhibition’s current iteration as 45 Stories in Jewelry closes April 10, 2022. It will return in the full gallery as Jewelry Stories, running July 12, 2022–April 16, 2023. It will be in the drawer cabinet only, its final resting place in the Tiffany Jewelry Gallery, May 10, 2023–an unspecified date. The Museum of Arts and Design’s exhibition page for Jewelry Stories is here.