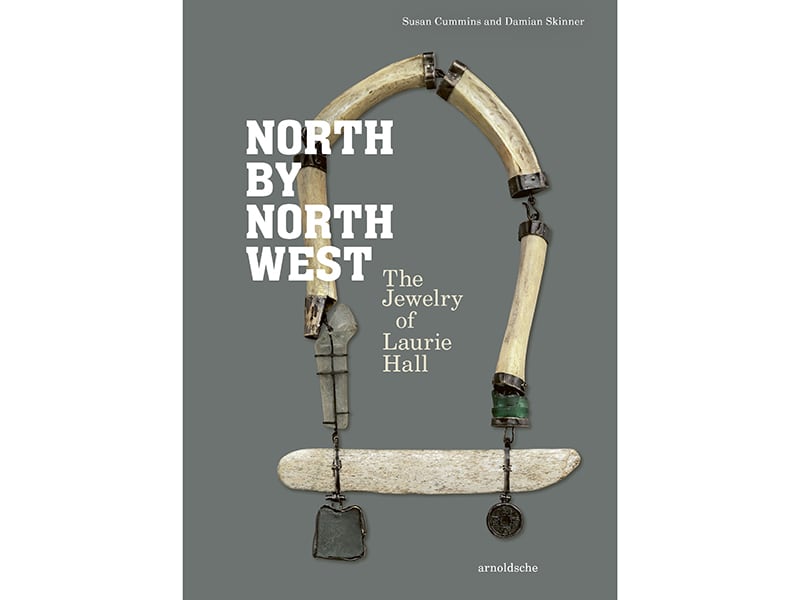

- The book North By Northwest is engaging, informative, and very ably researched, with a lively graphic design

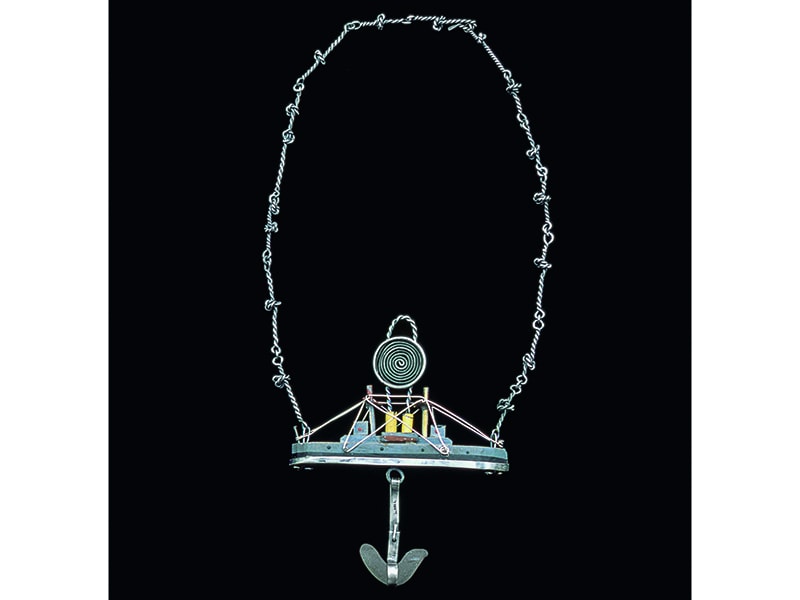

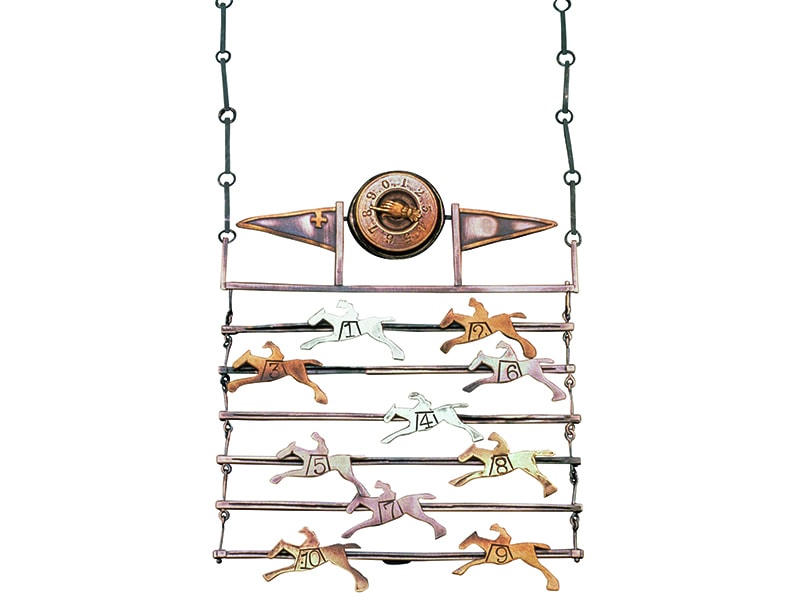

- Its large format is well-suited to presenting Laurie Hall’s work, which often consists of big narrative neckpieces with many components

- The authors present individual pieces with relevant backstories, personal circumstances, and useful explanations about social and historical references to effectively tease out and describe the meanings of the work

- The book was produced through AJF’s fiscal sponsorship program

Susan Cummins and Damian Skinner, North By Northwest: The Jewelry of Laurie Hall. Stuttgart: Arnoldsche Art Publishers, 2022.

Following the publication of In Flux: American Jewelry and the Counterculture, the art historian Damian Skinner and the gallerist, collector, and jewelry advocate Susan Cummins released North By Northwest: The Jewelry of Laurie Hall. In Flux (written with curator Cindi Strauss) was extremely broad in scope and will continue to serve as an important source of biographical and historical information about American studio jewelry that would otherwise be lost as jewelers, collectors, and advocates from the 1960s and 70s grow older. But monographs on single artists are another important part of preserving the history of the field and advocating for the strength and importance of jewelry as an expressive form of craft. (In the interest of full disclosure, I would like to note that Cummins and Skinner are currently working with me on a book about my own work. When I expressed concern about writing this review under those circumstances, Skinner simply replied “be critical.”)

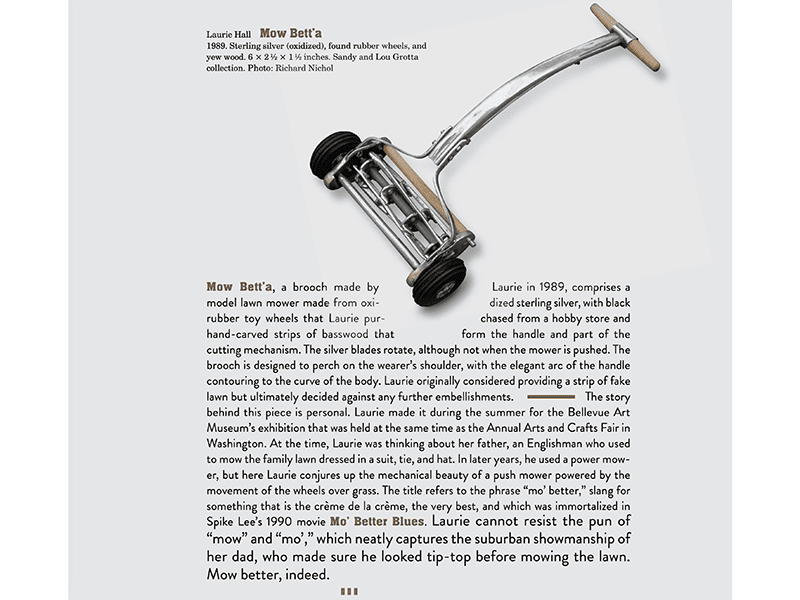

North by Northwest attempts to thoughtfully present and contextualize Hall’s work at both a personal and a social level. Hall (b. 1944) began her career as a jeweler in the 1960s, overlapping with the era covered by In Flux. At 11½ x 8½ inches, the large format of the book is well-suited to presenting Hall’s work, which often consists of large narrative neckpieces with many components. The graphic design is lively and engaging, with just enough quirkiness to complement the playfulness of the jewelry while still remaining readable. The designer’s decision to occasionally break up sentences with images, however, can be disruptive.

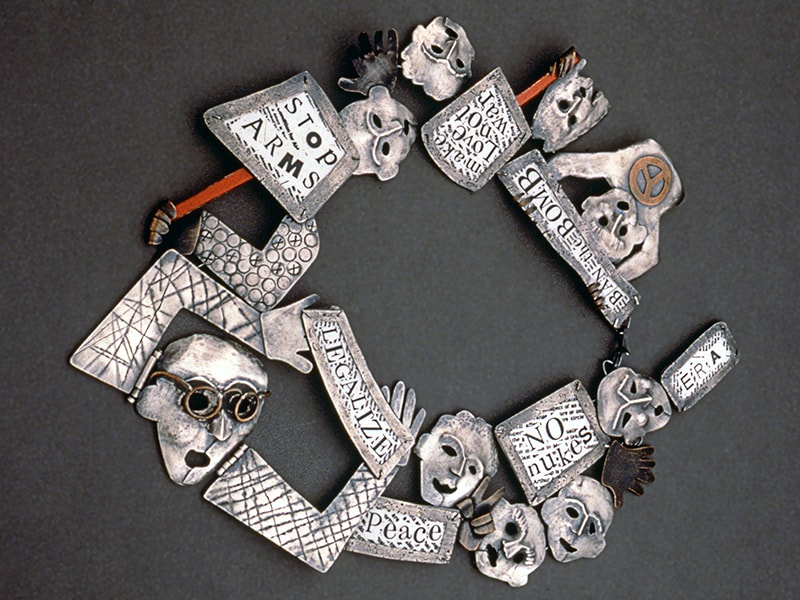

Hall’s work is quirky, playful, and humorous—often relying on puns and word associations for its impact and meaning. It is also self-consciously unrefined in its approach. Hall utilizes found objects and reference points like folk art and what she calls “camp craft”: the untutored and technically unsophisticated sorts of objects that she remembers making in summer camp. Her work also very significantly helped define the possibilities and set the parameters for a distinctly American approach toward jewelry as narrative and embedded in the personal.

Eschewing a chronological approach, the authors present Hall’s work thematically. They deal in turn with her personal tendencies and approaches to work, her deep associations with the landscape and history of the Pacific Northwest, her long experience as a secondary-school art teacher, and her identity as a member of the so-called “Northwest School of Jewelry.” The final chapter attempts to both synthesize the overall content of Hall’s work and sensitively raise some important and broadly relevant issues regarding the ways that social changes can expose unquestioned or outdated notions and biases in an artist’s work. This thematic approach works extremely well, allowing the authors to better explore the resonance between pieces made decades apart.

Great efforts are made to present individual pieces with relevant backstories, personal circumstances, and useful explanations about social and historical references. Hall herself is quoted frequently, giving the reader direct and intimate access to her thoughts and creative practice.

The authors strive to place Hall’s work in the context of what has come to be known as the Northwest School of Jewelry, which is broadly considered to consist of narratively driven work which to varying degrees utilizes found objects, straightforward and unfussy technique, social commentary, and humor. It stems from the Seattle-based influences of Ruth Pennington (1905–1998) and Ramona Solberg (1921–2005) as well as from “Ellensburg Funky,” which was based in Eastern Washington and centered on the jeweler Ken Cory. The approach also encompasses a number of other jewelers who were drawn to some of the same technical strategies and who often utilized found objects (such as wooden rulers) as well as various forms of humor and wordplay, ranging from the broad to the sly.

For Hall, Solberg was the most influential mentor, not only because she was generous with her time and feedback, but also because her collages of items collected on her travels suggested numerous expressive possibilities unburdened by the constraints of traditional jewelry forms and materials.

Cummins and Skinner do an exceptionally good job of characterizing the work of the three jewelers most closely associated with Solberg: Kiff Slemmons (b. 1944), Ron Ho (1936–2017), and Hall herself. The book explores their relationships with Solberg while carefully distinguishing between their divergent artistic goals. As the authors note, Solberg, while appreciative of the origins of her found objects, treated them primarily as design elements, grouping them formally rather than conceptually or culturally. Hall, meanwhile,used found materials to tackle contingency, memory, and anecdotal experience. In contrast, Ho engaged with issues of identity and origin, and Slemmons with taxonomy, systems, measurement, and scrutiny.

The authors briefly contrast Hall’s use of humor in jewelry from that of Merrily Tompkins (1947–2018), who was closely associated with Ken Cory. But they miss the opportunity to more fully explore the reciprocal influences between the three female jokesters of Northwest jewelry: Hall, Tompkins, and Nancy Worden (1954–2021). There is a great deal of strategic overlap in the use of humor between these three important jewelers, and teasing out the distinctions between Hall’s gentle puns, Tompkins’s bawdiness, and Worden’s confrontational sarcasm would be a task worth exploring.

The large number of pieces pictured and described allows the viewer to reflect on the specific ways that Hall’s jewelry functions on the body. In discussing Hall’s neckpiece The Protestors, the authors note how this depiction of protest signs and faces causes the wearer to become “immersed in the crowd, surrounded by the demonstrators.” This leveraging of the site of the body—and the relative positions of wearers and viewers—to stretch single-point representation into multi-point narrative is masterfully managed by Hall on a number of occasions and effectively demonstrates the underdiscussed and underexplored potential of jewelry for expressiveness unattainable in other art forms.

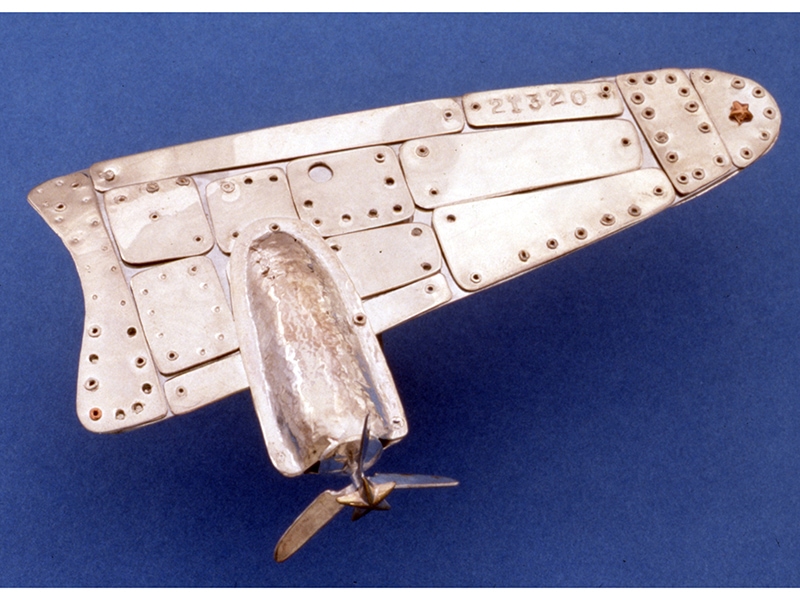

In one case, Hall places toylike airplane wings, referencing the Gulf War, onto the shoulders as epaulettes, thus both infantilizing and personalizing the urge to fight. She uses interlocking jigsaw pieces and riveted plates to reinforce the wings’ respective titles of Puzzling and Riveting, referencing opinions about the war. In the neckpieces Help, Help, House on Fire and Rah, Rah, Sis Kum Bah!, she cinematically extends an instant into an event by utilizing both the front and back of the body, significantly enhancing the impact and meaning of the pieces.

Underappreciated in the usual discussion of Hall’s work is her remarkable ability to create dynamic formal arrangements that help support the conceptual interplay of components and complement/compensate for her generally casual technique. Pieces like Stanley Helps You Do Things Right?! and Cubist Café are miracles of taut, compelling balance and energy.

However, while effectively teasing out and describing the meanings of the work, the authors occasionally try a bit too hard to make the case for pieces that are far less successful than others. Hall doesn’t always strike the right balance among her recurrent strategies of evocative found objects, dynamic placement, unfussy “honest/direct” craft, and verbal/visual humor.

Pieces like Steal and Scarecrow squat rather awkwardly, and discussion of why some pieces function better than others would have been a welcome addition to the book and would help introduce more critical discernment to the field. Whether objects succeed in their goals—and precisely how they function—is rarely discussed. Reviewers and supporters tend to grant too much significance to what an artist intended to say, rather than to what they actually managed to induce the object to mean.

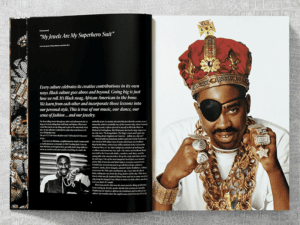

Hall works in a very personal and nostalgic way, drawing on her family background, her life experiences, her responses to found materials, and her identification with the Pacific Northwest. Not surprisingly, that means that the work reflects her identity as a middle-class white woman born in the 1940s. Consequently, some of the work—and perhaps her way of working itself—can be seen as somewhat dated and as reinforcing aspects of power and privilege. This includes occasionally utilizing cultural appropriation and touching on race in ways that have not aged well.

Pieces like Silver Salmon Ceremony and Chief Bone Gone Fishin’ Bone Fish rely on stereotypical physical depictions and social notions of Native Americans that we now understand as forms of othering and mythologizing. We have been slowly reckoning with this, including in heated discussions about sports mascots and team names, and we can see the same forces at work in the book.

Even Hall’s reliance on folk-art strategies and camp craft can be seen as a kind of “class tourism,” dipping into the visual production of other socioeconomic groups and reductively reaching for some kind of visual “honesty” and “directness.” The very structure of summer camp was—perhaps still is—embedded in this kind of founding-mythwishery: getting “back to nature,” “roughing it,” making “native-style” objects, learning “woodcraft,” etc. But of course at the end of the week Dad picked you up in the station wagon and you got to have a milkshake on the way home …

This is not intended as an indictment of Hall, but rather as a reminder that work can carry unintended meanings and that as it passes through time some of those embedded and unrecognized meanings come into focus. In my own case, I felt this recently while reviewing some of my own work from 20+ years ago. That particular work dealt with the notion of sexual emancipation. I came to realize that it relied heavily on the gender binary as a conceptual anchor and thus had aged very poorly indeed! Rather than being as maximally inclusive as I intended, the work has come to read as exclusionary and narrow. Society moves faster than objects do.

It was gratifying to see Skinner and Cummins grapple head-on with these issues in their last chapter. Without diminishing Hall’s considerable accomplishments as a jeweler, they explore and contextualize her occasional use of themes and reference points that have grown more problematic over time. They compare them to similar efforts by J. Fred Woell and Ken Cory, and do not shy away from pointing out the social meanings and assumptions embedded in the work.

As a counter to these concerns, Hall’s work forthrightly reflects her personality, her humor, and her capaciousness. What never seems to appear in her work is any conscious hostility, anger, disrespect, diminishment, or impatience. This, in itself, makes the instances where she falls back on questionable social tropes worth thinking about without rancor or blame. It allows what now may seem inappropriate to be contextualized within a larger body of work that is wry, joyful, engaging, and kind.

In ending the final chapter with a small number of pieces that incorporate cross-cultural influences (perhaps appropriation), the authors seem to offer the reader an opportunity not only to compare those works to the rest of Hall’s oeuvre but to interrogate their own assumptions and privileges.

North By Northwest is engaging, informative, and very ably researched. It gives the reader significant insights into Hall’s work and adds to a deeper understanding of the influences that impacted her and other jewelers in the Pacific Northwest, as well as to the broad impact that her work has had on expanding the language and potential of jewelry.

© 2023 Art Jewelry Forum. All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. For reprint permission, contact info (at) artjewelryforum (dot) org