Deganit Stern Schocken: How Many Is One: Jewellery/Objects/Installations, Stuttgart: arnoldsche Art Publishers, 2021.

Like her jewelry, the title of Deganit Stern Schocken’s monograph, How Many Is One, is intriguing, stimulating, not easily unraveled, but rewarding when you pry deeper. Even the first word “How” in the unpunctuated title is challenging as it can be read as a positive endorsement or as an implied question.

This is not a book for the casual reader, but for someone willing to spend the time to trace a career forged in a country where political controversies affect every aspect of life, including aesthetics. Although synonymous with Israeli contemporary jewelry, Schocken has established an international reputation, and this is underscored by this volume in English, with no text in Hebrew.

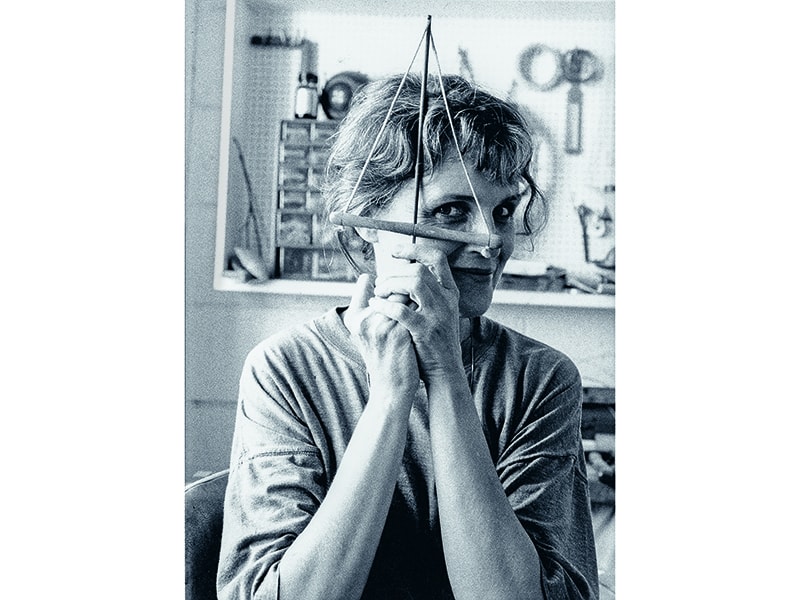

This well-structured publication is a welcome addition to the modest number of in-depth monographs on Israeli art jewelers. For more than 40 years, Schocken has influenced Israel’s small but vibrant art jewelry world as both artist and teacher. She has achieved international recognition as a probing jeweler unafraid to challenge and provoke her audience.

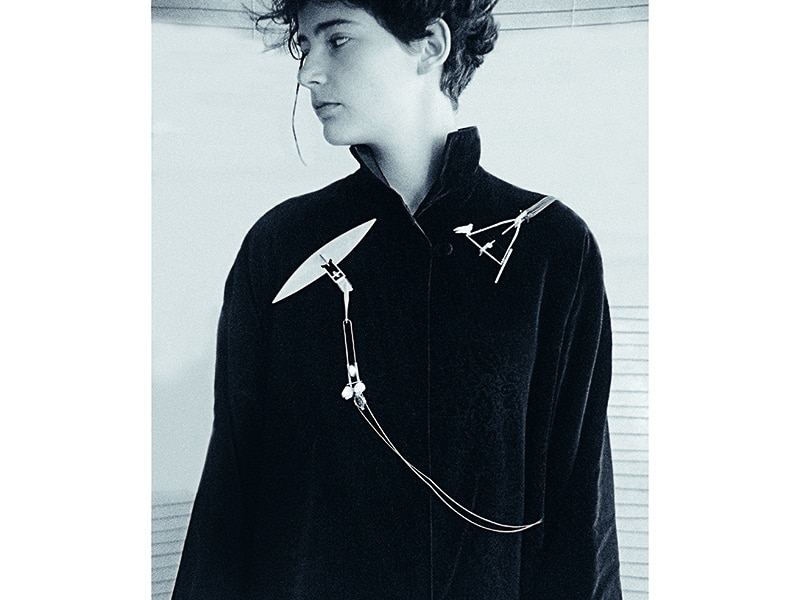

The book’s 327 pages are filled with full-page color and black and white photographs of Schocken’s jewelry, many worn on the body, together with installation shots. The abundant illustrations cover the breadth of Schocken’s achievements, but it is not always easy to connect the photographs with explanatory texts. The layout highlights the artist’s creativity and prolific production over her long career. With its unconventional essays by writers from diverse backgrounds in anthropology, psychology, philosophy, and poetry, this is no ordinary jewelry book. Schocken chose these authors because their insights and unique perspectives reflect the sophisticated intellect with which she approaches her work. She expects the reader to follow the explorations of her keen mind. I found the experience rewarding.

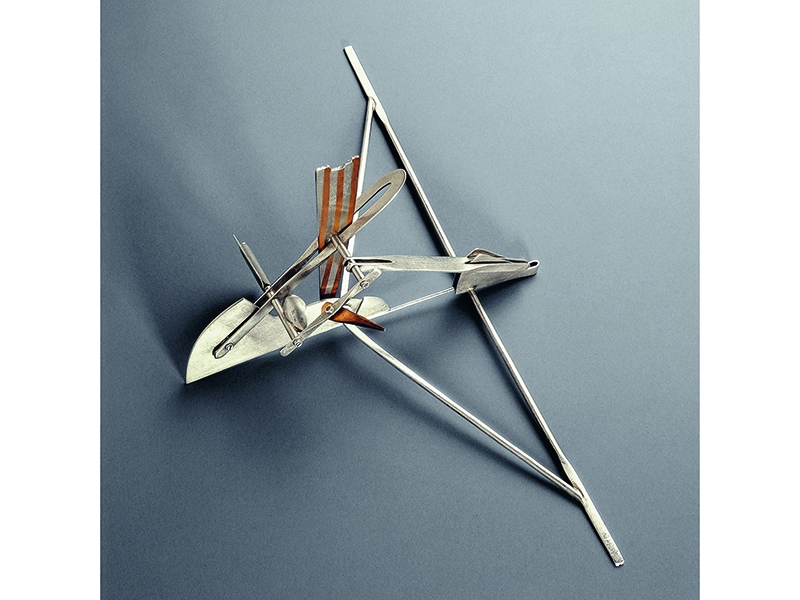

The book covers Schocken’s oeuvre beginning with her early work from the 1980s, when she concentrated on function and structure. Executed predominantly in fine silver, these designs are aligned to some degree with earlier European jewelry, particularly that of Scandinavia in the 1960s and 1970s. Her work also recalls modernist American jewelers working in a reductivist style, but with greater emphasis on an architectural approach. Schocken’s exceptionally strong voice is reflected most fervently in later work where the stressful and emotionally charged sociopolitical existence in her native country is conveyed.

In the Introduction, Israeli art historian and curator Iris Fishof sets forth a clear and lively chronology of Schocken’s impressive oeuvre using helpful page references to illustrate her discussion. Fishof guides the reader through the artist’s evolving themes and approaches marked by key events and exhibitions. Many of these serve as guideposts to the twists and turns of a remarkably inquisitive mind. Fishof shows Schocken as an artist with the ability to transform her responses to what was happening around her into deeply felt and provocative jewelry.

The majority of the book consists of four chapters, based on single words from the title: “How,” “Many,” “Is,” and “One.” Each chapter discusses a different aspect of Schocken’s work.

The “How” chapter, subtitled “Function as Expression—Expression as Function,” focuses on the influence of her studies of architecture. It contains many examples of works that deliberately expose the normally hidden functional elements, notably the fibula based on the safety pin principle and originally used to fasten Greek and Roman garments. This chapter consists of a dialogue between Schocken and design anthropologist Jonathan Ventura, with pages filled with numerous works that illustrate the balance she sought between function and aesthetics.

The next chapter, “Many,” is subtitled “How Many Is One/Ants.” It conveys Schocken’s views of the reciprocal relationship between jewelry made as craft versus those pieces made as industrial products. The three essays are by Meira Yagid Haimovici, senior curator and head of architecture and design at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art; Uriel Miron, professor at Shenkar College of Engineering, Design and Art; and Itzhak Carmel, clinical psychologist. The chapter contains photographs of the brilliantly designed 2003 exhibition How Many Is One, at the Tel Aviv Museum, which demonstrates how an industrial object can be individualized through permutations of multiple castings of the same piece. The chapter concludes with numerous views of Ants, a 2009 installation in which Schocken generated a colony of insect-like creatures, created from outdated castings, marching along the length of the Petah Tikva Museum of Art. As Miron observes, it represents “an in-depth investigation of an industrial process and its intersection with art and design.”

The “Is” chapter deals with the concept of value in jewelry-making and object design. The sole essay, The Fisherman’s Equipment, is by Dutch art historian and curator Liesbeth den Besten. She traces the elusive character of Schocken’s decades of jewelry-making and her ability to transform everyday things into humanistic jewelry that connects people.

The fourth chapter, “One,” subtitled “Local/Political,” deals with Schocken’s deep concern for social and ecological issues and the complex reality of life in Israel. The first of its two essays, The Apparatus, is by Israeli art critic and philosopher Gideon Ofrat. He takes the reader on a philological and historical exploration of the many meanings of an apparatus. Illustrated abundantly, the section conveys the ways Schocken transforms found objects. It also explores how she inserts texts and labels to create vibrant jewelry and objects that are alive with incisive and often provocative or subversive messages.

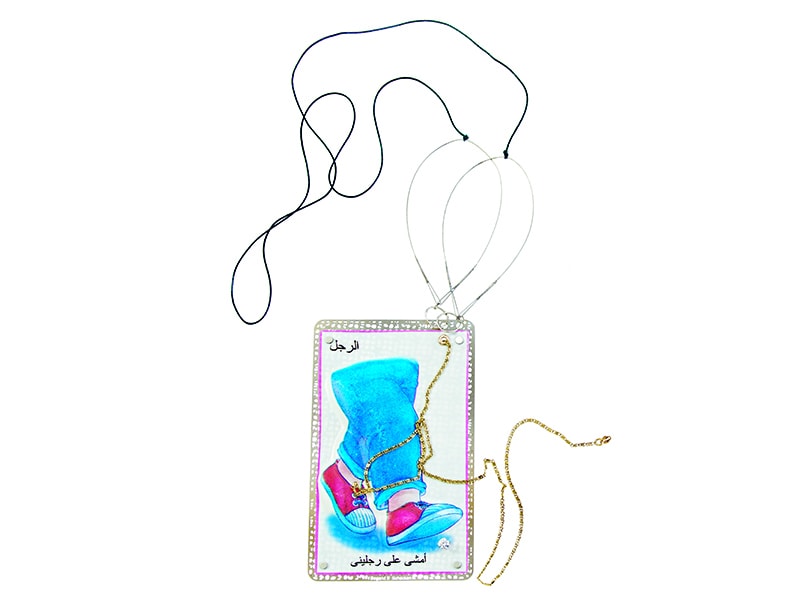

Ofrat mentions the tension Schocken exposes between the individual and society, particularly the relations between the Israelis and Palestinians who live alongside and apart from each other. In her 2009 Figure of Speech series, she added gold and silver chains and cubic zircons to the simple plastic boards used in schools to teach Arabic. The work serves as a concealed message demanding a willingness to accept the other.

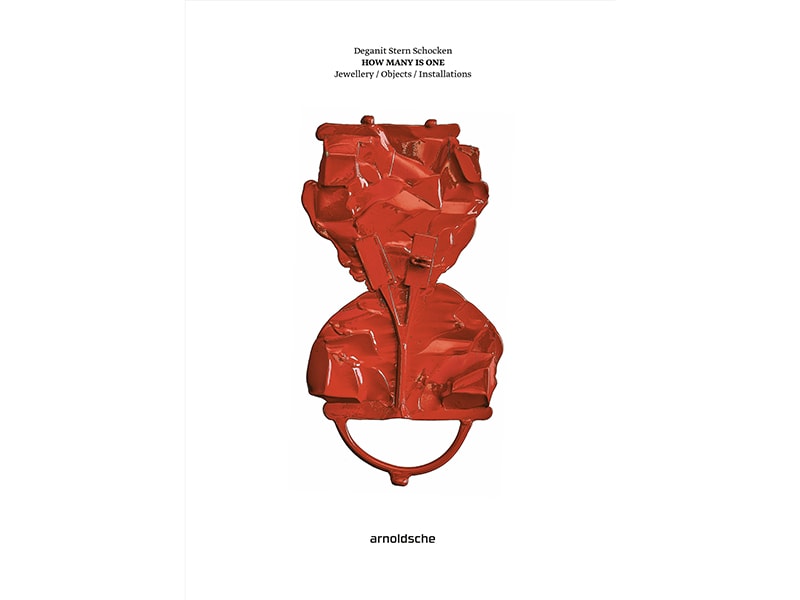

To my mind, there are no more potent sociopolitical images than those in the 2007 series, Qalandia Checkpoint, which features crushed beverage cans with Arabic labels that serve as a metaphor for the crushing of a people’s rights. Setting the cans with diamonds or cubic zircons transforms the casually discarded objects into wearable pieces, reinventing them to intensify her powerful message.

Multidisciplinary jewelry artist Helen Britton authored the next essay, Urban Jewellery Event. She takes us on an imaginary walk through a city that analogizes the body as “a cityscape, punctuated by jewelry events that are portals to ideas.” The wearer completes the “event” by donning the jewelry piece whose structural components, whether visible or concealed beneath the façade, express Schocken’s idea of “function as expression.” Britton notes that Schocken’s work incorporates her architectural foundation but evolves into works that span cultural, social, and political concerns.

The concluding essay, How Many Is Deganit? is a tribute to the artist by prominent Israeli poet Aharon Shabtai. He uses the world of Greek mythology to open unexpected perspectives into jewelry in general and Schocken’s work in particular. With keen observations on the jewelry that bring a number of Greek myths to life, Shabtai illustrates the daimonic power of jewelry, which lies in its dual overt and covert nature. In arguing that jewelry can conceal (or deceive) but can also expose and uncover, he conveys a deep appreciation for how Schocken’s work both reveals and conceals its maker. Seen through Shabtai’s Greek ideal prism, Schocken’s jewelry “conceptually illustrates the ethical beauty of the concept of the body perceived as a geometric, calculated, architectural form comprised of organs held together by hinges that allow movement and action.”

Schocken’s curriculum vitae completes the book. It covers her birth in a kibbutz in Israel’s far north; her BFA degree from Bezalel Academy of Art, in Jerusalem; and the MA from Middlesex University, in London. Then there is her long and distinguished career at the Shenkar College of Engineering and Design, where Schocken served as the head of its master’s degree program. She also founded the Inyanim Group of Israeli jewelry artists. Her impressive list of exhibitions, participation in symposia, and appearances in major collections occupies more than six pages.

For those familiar with Schocken, the book provides the definitive examination of her career. For those new to her work, it is an eye-opening introduction to an important international artist who creates jewelry from many diverse approaches, using a keen intellect and mastery of materials to realize its power and potential.

To purchase this monograph, visit Charon Kransen Arts.