When you’re born with the name Ulysses Grant Dietz, you just might have come into this world with a penchant for leadership. Luckily for the art jewelry community, Ulysses turned his attention not to military or political affairs, but to a life’s mission of preserving, protecting and defending his nation’s artistic heritage.

As senior curator and Curator of Decorative Arts at the Newark Museum, with its 80 galleries of display space, he oversees a collection that begins with jewelry but ranges out to ceramics and silver as well. In other interviews, both in print and on video, Ulysses has been labeled a ‘national resource,’ a man with ‘encyclopedic knowledge (who) has helped put the Newark Museum on the map as a vanguard of modern decorative arts.’ When you talk to Ulysses, it’s clear that he carries a love for the objects in his collection almost as much as the attachment for his own children. That’s why he refers to museums as the proper home for things of fragile beauty, because ‘it’s safe.’ Protecting the precious, whether infants or aged art jewelry, is a mark of the character of Ulysses Grant Dietz.

In 2009, Elise Winters asked him about his background as a curator.

Elise Winters: Where were you before Newark?

Ulysses Dietz: My training as a decorative arts curator began in 1978 with a graduate program through the University of Delaware. I was a graduate fellow at the Winterthur Museum outside of Wilmington, starting at the Newark Museum in 1980 with a special interest in the nineteenth century and then expanding since then to the present day. I’ve been particularly interested in jewelry more recently, especially as it connects to the decorative arts.

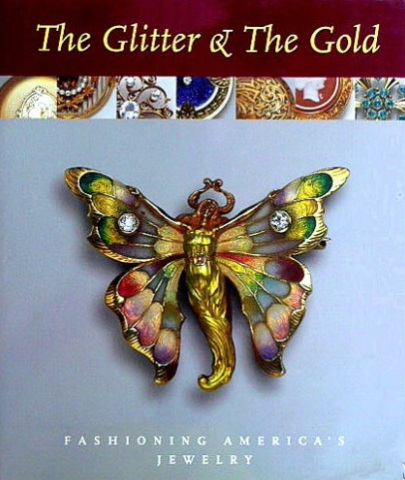

That goes back about a dozen years to the 1997 show, The Glitter and the Gold, an exhibition I co-curated with Janet Zapata about the gold jewelry industry in Newark. A lot of people might still be unaware that Newark was the center of solid-gold jewelry manufacturing from the 1850s to the 1950s. For decades, there wasn’t a jewelry store in America that didn’t carry Newark’s goods. As long as there was this kind of industry in America, Newark was its capital, producing 90 per cent of the gold jewelry in this country at its peak. For instance, there was Krementz and Company, the last survivors. They didn’t sell under their own name, but manufactured for Cartier and Tiffany in their Newark factory. It was a kind of industry practice to remain anonymous in favor of the retailers. In our newest gallery today, there’s a section on Newark jewelry.

I’d like to know more about the new gallery.

We’ve just opened this last August. It is called the Lore Ross Jewelry Gallery. Mrs. Ross left the museum a large bequest and we named a permanent jewelry gallery in her honor. In the gallery we have jewelry from the 1600s to the present day. Even without extensive publicity, people in the jewelry world have come to see the collection and learn about it. In the museum, we’ve created a context for Newark’s jewelry, but have long had a focus in acquiring European and American work as well. For instance, we bought two pieces of George Jensen jewelry back in 1929.

How does your jewelry collection serve your local community in Newark?

We think of our local community as all of the 2.5 million people in northern New Jersey. And yes, we think that jewelry is of interest to everybody and that the interest is endless.

Why would the Newark Museum be an attractive venue for jewelry donations? If somebody is interested in donating, there are so many other prominent places that would come to mind.

Well, let me admit that the Metropolitan Museum in New York City does have glamour that we can’t match and frankly, it can get anything that it wants. But really, what can you give them that they don’t already have? I can make a clear claim that we are more committed to jewelry than most other American museums, including the Met, are. Our dedication to jewelry as a medium is well established with the galleries we have built.

Collectors have donated to the Museum of Art and Design, but MAD’s interest centers on contemporary studio jewelry, both wearable and unwearable. For me, wearability is crucial; I can’t buy a piece of jewelry that can’t be worn.

To us, contemporary art jewelry fits in as a component of our larger vision about what constitutes the decorative arts. The way my department collects is to document interaction between design and production in daily life. This is a museum of objects that interact with the way people live. And I believe that when people visit the Newark Museum they come to see jewelry that informs, that sheds light on history.