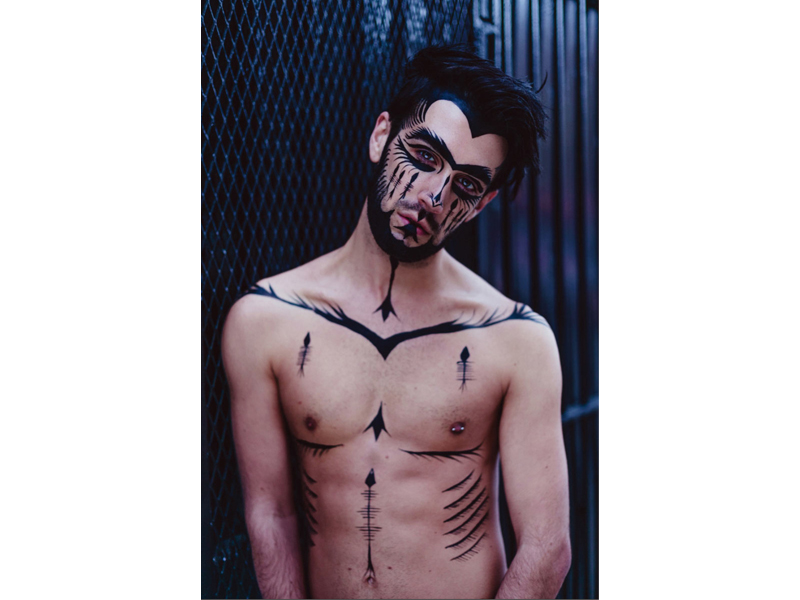

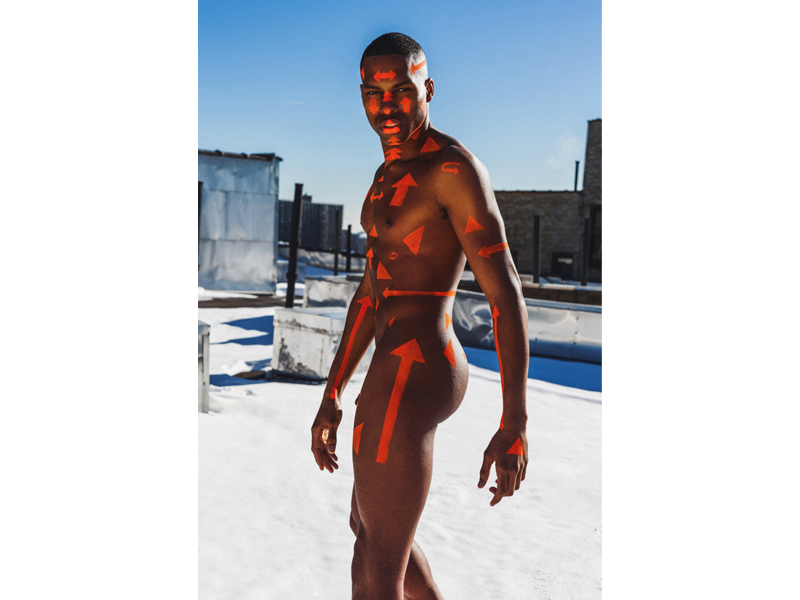

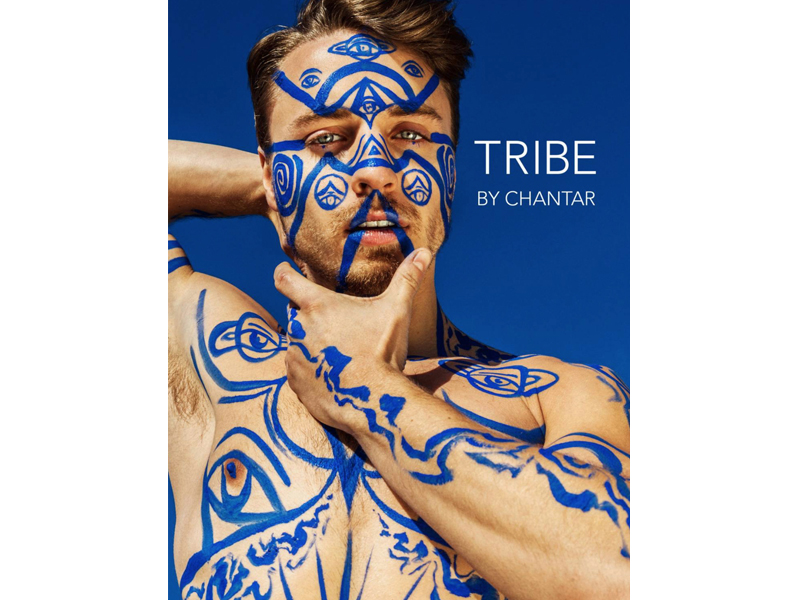

Cut flowers are an iconic representation of ephemerality, the cycle of beauty and the process of death. Flowers and Tribes, two photographic series by New-York-based Travis Chantar, depict young, nude sitters adorned with ephemeral petal arrangements and body-paintings. I was interested in having a chat with him for three reasons: His work blurs the lines between fashion, performance documentation, and portraiture; he recasts the viewer as a voyeur of what seem like the intimate rituals of fictional tribes; he pushes adornment in a space that is queer, but only exists as a fleeting, fragile moment. He kindly agreed to answer my questions.

Matt Lambert: Tell us a little bit about your personal background. Where were you born, and what memories remain significant about growing up?

Travis Chantar: This subject is a bit complicated. My ethnicity is mixed, Thai/white (Irish, German, French). I was born in Downey, California, and raised in Pocatello, Idaho, by my two (lesbian) mothers. My favorite childhood memories include a great deal of camping and exploring nature in Idaho, as well as making a big deal of every holiday. My mother had a rough childhood, and wanted to make sure I was able to experience “normal” family life … as much as possible. I also got to visit my Thai father in L.A. throughout my upbringing, and have always been fond of the big city and culture therein.

Where did you learn the techniques and skills to produce your work? Are they, as I imagine, largely self-taught?

Travis Chantar: When I was young, I suffered from drastic asthma symptoms. This kept me sitting still, painting, drawing, and creating random paper decorations. So I think an affinity for all things artistic grew naturally. I loved crafts, and decorating people is actually quite similar.

What feeds your inspiration? What do you look at when starting a new body of work? Lets start with the series Flowers.

Travis Chantar: Growing up, I was obsessed with plants and took apart all the flowers to see what was inside. What struck me was the detail and symmetry in nature. The patterns continue through to the cellular level and beyond. Life grows in beautiful structure. As far as inspiration goes, I think you can catch it from literally anywhere, you just have to be paying attention. Even an off-handed comment from a passerby can strike a match in your brain, firing up a memorable image, a staggering question, your next brilliant idea.

How do you connect with your models? Do you seek them out, do you already know them, or is it more of an open casting call?

Travis Chantar: Often they are friends, people I meet through work, or creatives reaching out to me via social media (often for head shots or portfolio work). As a young artist in NYC, I have to make a living as well as pursue my art. Therefore I try to add creativity to everything I do, allowing me to make something I can “use” for art from every shoot I do, no matter how banal.

In regards to your Tribe series, an article in OUT magazine states that you paint your models to match their auras. How do you connect with your model to know their aura? Does this same concept apply to how you choose species and placements of flora and fauna in your Flowers series?

Travis Chantar: I believe the best way to make art is to set the subconscious to work. If one attempts to consciously decide exactly how the image should look, beforehand, it really doesn’t allow space for the genius of the moment. My favorite work is absolutely surprising to me, and when I finish, I think, “How did I even come up with that?” Well, I didn’t. I allowed the personality of my subject, as well as mood, weather, and the situation, influence my work. Flowers is a very similar process.

The Tribes and Flowers series find similarities in tribal body painting from around the world, in particular African tribes from the Lomo region, in Ethiopia, who use both plants and paint. I see a connection there, but I also see differences: Your “tribe” does not exist prior to your photographing it. One could say that you “invented” it. Is that the case?

Travis Chantar: Everything has been done before, so I could never take credit for inventing anything. However, I am particularly interested in universal elements of humanity, and ritualistically decorating bodies is essential to human cultural development. I think decorated images of humans resonate with cultural significance, and my goal is to create culture we can all relate to as humans, regardless of ethnicity or social class.

![(left) Hans Silvester, Natural Fashion No. 113, 2007, from the series Natural Fashion-Tribal Decoration from Africa, C-print, 100 x 69.9 cm, edition of 10; (right) Jimmy Nelson, Arago, Korcho Village, Omo Valley, Ethiopia, 2011, from the series Before They Pass Away [this second picture has been cropped from the original]](/sites/default/files/7.16_AINT_MLAMBERT_Chantar_4_600x800px.jpg)

How does the photograph fit into your process? Do you see it as an object itself, or does it function more as a documentation of ephemeral mark-making on the body? How different are the Tribe or Flowers images from a fashion shoot?

Travis Chantar: Photography is a tool in the image-making process. I imagine many of my portraits more as paintings, as far as composition and colors go. The difference between my art series and fashion? Clothing, mainly. 😉

How much postproduction editing do you do?

Travis Chantar: The editing is yet another brush in my tool kit. That being said, I like the images to retain photographic integrity as opposed to an actual digital painting. So the decorations are all done in real life.

How important is the element of ephemerality to your work?

Travis Chantar: Personally, I like fantasy and transformation. I am a dreamer, and I like to create dreamy work, with vague context. I think this encourages viewers to come up with their own interpretations.

In an interview with Logo Magazine, you state “adding decoration and ritual transcends money.” I am wondering if you could expand on this thought? Does it mean that these images exist outside a market of exchange and payment?

Travis Chantar: This is actually an integral part of my work, and goes back to how it differs from fashion. When I first moved to New York, I was in a magazine shop doing research. Every artsy magazine, featuring an aesthetic interesting to me, was fashion. Fashion is a commercial venture (with artistic value), but it’s selling a product. It often feels as though the quality of images is judged by how “expensive” they look. Well, I wanted to create images to challenge this idea, by using free materials. In my mind, art trumps money. That’s why art is used to sell everything, and the most “priceless” objects in the world tend to be art. Whether it’s the Mona Lisa or a pyramid, we value aesthetic creations above almost all else, and travel the world just to see them.

In a lot of your images there is a tone of sensuality or eroticism. How does this element function in your work?

Travis Chantar: I think so much of humanity goes back to sex. It really is one of our main biological goals in life and we can’t escape it. However, I believe nudity isn’t inherently sexual, so most of my work isn’t particularly sexualized, and sex isn’t the main focus. The beauty and characteristic individuality of my subject is the focus, and that can sometimes be the sexiest thing.

How does the idea of queerness function in your work? What other queer work being made today do you feel your work has a dialogue or relationship with?

Travis Chantar: I struggle with the categorical groupings of race, sexual orientation, and gender forced down our throats by limited societal narrative. My understanding of queerness is the space between these ideas, which are all spectrums, furthering the diversity of life on Earth. Queer work is any work furthering this idea, and we are all united in overturning the oppression of a hierarchical system, in place to keep power in the hands of the greediest and wealthiest. I have respect for anyone who creates work powerful enough to open minds.

Ideas and traditions of decoration and ritual heavily surround jewelry. How do you see the relationship between jewelry and how you adorn bodies with paint or flowers? Do you think that jewelry is part of the wider conversation on gender?

Travis Chantar: Jewelry is a powerful identifier of gender, culture, and social class. I find it interesting how American culture feminizes all decoration (in my opinion to frame women as objects of beauty and men as consumers of that beauty). However, all over the world, elaborate jewelry is worn by both men and women. I wish our culture were not afraid to decorate men, and I honestly believe everyone should be forced to try drag at least once! 😉

Where can we see more of your work? Do you have any upcoming projects on the horizon that we should be looking out for?

Travis Chantar: My most current platform is Instagram (@chantar). I have so many ideas I would love to turn into their own series, but I need to figure out a way to be financially stable in New York first. Next I will release a book of my work with flowers on people, which will be accessible to buy via my website.

What has your interest at present? What was the last thing you read or saw that captivated your attention?

Travis Chantar: #blacklivesmatter, trans rights, and basically fighting dehumanization of cultural and racial “others” often captures my attention. Also, I am extremely vigilant about the importance of dismantling insecurities, because they do nothing but keep us from our own goals. Artist who I love on Instagram: @heyrooney, @thismintymoment, @buttonfruit, @ryanpfluger, @isamayaffrench, and—guilty pleasure—@portiswasp1.