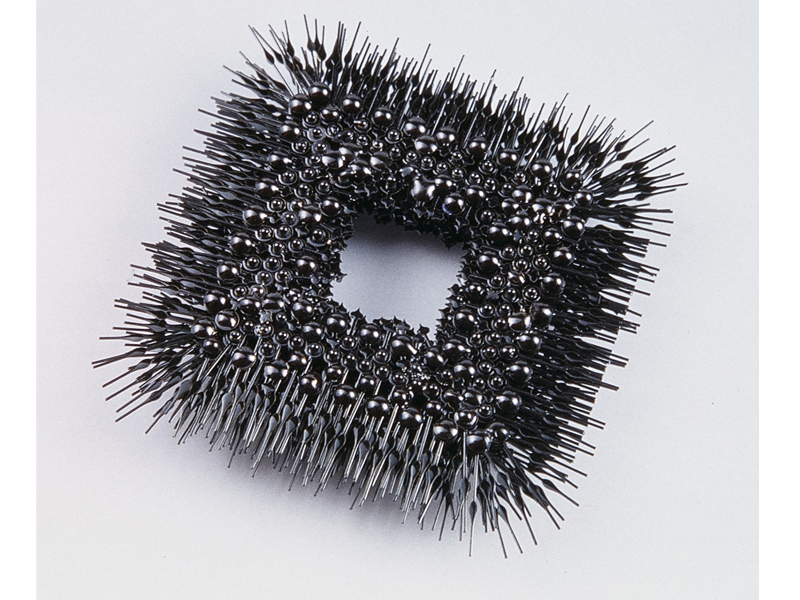

Sergey Jivetin is recognized for masterfully manipulating unlikely materials—such as watch hands, eggshells, needles, and steel jeweler’s saw blades—into poetically articulated forms exhibiting a softness contradictory to their brittle materials. In 2005, Art Jewelry Forum awarded Jivetin the Emerging Artist Award (now called the AJF Artist Award) to celebrate and support his creative research. Jivetin’s recent projects continue this playful approach, incorporating performance and engaging the community. In this interview, he discusses two recent collaborations, Furrow and Spectacle, which engage with the processes of food production and consumption. AJF is pleased to present his continued research to inspire and engage young makers in anticipation of the next AJF Artist Award application process, which will be open for applications in Summer 2017.

Adriane Dalton: Where are you from, and where do you currently reside?

Sergey Jivetin: I was born in Uzbekistan, but have lived in the US since 1992. I currently reside in the Lower Hudson Valley, in New York state.

What initially drew you jewelry and metalsmithing as a mode of expression?

Sergey Jivetin: I was drawn to three-dimensional miniatures from an early age. Common, easily workable metals (I started with aluminum foil and lead) were one type of material I embraced. Jewelry was the most direct and universally recognizable format to apply that passion to, so I decided to explore that avenue.

Recycled, repurposed, and alternative materials feature prominently in your oeuvre. Describe your relationship to these materials and what compels you to work in this way.

Sergey Jivetin: For some projects, the fact that a material is recycled adds a layer of meaning and purpose, and while this dimension is intentional, it’s not exclusive. If a project conceptually calls for commercially available raw stock, I will use that, or will work with a manufacturer to customize it—like sourcing the 85,000 watch hands used in the Time Structure series. Some projects develop directly as a consequence of the recycled origin of the material itself. In Chalice, a speck of gold dust is fashioned into a tiny vessel with a volume of one drop of water. The fact that the gold was mined in the Sierras, now suffering from the effects of climate change, underlines the conceptual emphasis of the entire piece.

Do you happen upon the materials which then shape your creative practice, or do you seek them out intentionally based upon an idea?

Sergey Jivetin: My thinking behind the application of materials toward the idea has been evolving. In the work made soon after grad school, from around 2003 ’til 2007, I prioritized material exploration for aesthetic purpose, only tepidly testing materials’ potential to carry complex meaning. Afterward, it became a much more integrated process, where a material I’ve previously worked in would seem to befit the new idea, or I would start engaging with a new material after selecting it for an idea out of many options.

I now aim for projects where concept, materials, technique, and aesthetics are so naturally integrated that a question of which goes first won’t arise.

Reincarnated is the most recent attempt. It’s a permanent installation that came together conceptually and physically as a result of a problem I was asked to address: a bullet hole in a stained glass window of a former church. In the solution, a forensically reconstructed bullet slug became the physical and conceptual structure for the tiny precious stone-studded rose window plug.

Your conceptual tableware series entitled Spectacle combines antique lenses with cutlery for the Dutch company Steinbeisser’s Experimental Gastronomy project. How did this collaboration come about?

Sergey Jivetin: Out of the blue. I was contacted by the organizer, who mentioned seeing my work at a group project in the Netherlands several years before.

What inspired these objects? Is the tableware functional or purely decorative?

Sergey Jivetin: The inspiration actually came from my garden and personal culinary experiences. I would often inspect fine elements of plants before preparing dishes. The pieces from the Spectacle series are fully functional in their ability to transport food bites from a plate to the mouth, but their optical components ask the diner to pause, inspect, play, and wonder at the marvels of nature and culinary skill before consuming the food.

Describe for our readers what a day in your studio is like. What’s your work environment, and under what circumstances does your practice thrive?

Sergey Jivetin: The layout of my studio, tools, processes, materials, and work schedule morph from project to project. My studio has lots of high- and low-tech equipment, but the majority of space is taken up by piles of materials and half-realized projects. I often feel that most of the time I’m simply shuffling things from one pile to another. But interesting thoughts develop during those transplants.

In a 2005 interview, upon receiving the AJF Emerging Artist Award, you spoke at length about the financial constraints of working conceptually in jewelry. You cited the economic challenges of creating work that isn’t always directly marketable. Does this still resonate for you 15 years later? How do you navigate these issues as your career progresses?

Sergey Jivetin: I still believe it’s next to impossible to subsist on making non-market-oriented jewelry, or any innovative and challenging art in any format for that matter. I know of only a few experimental artists whose full-time practice can be considered a sustainable career. So some time ago I stopped imagining that my art can officially be called a career. But it still took me 20 years of struggle to get to the point of not holding my breath for work to sell. The moment of liberation came only when I found a skilled labor gig that paid well and yet didn’t take too much of my time.

This brings me to your current project, Furrow, for a residency at CHRCH Project Space in upstate New York in collaboration with the Hudson Valley Seed Library. Can you begin by talking about the inspiration and purpose of this community-engaged project?

Sergey Jivetin: The Furrow project engages in the debate of the very complex motives and consequences of plant domestication. Seeds are a powerful metaphor containing a wealth of histories and associations. In this first installment of the project, along with seeds, many participants bring and share stories of the connection of particular seeds to their lives. Through dialogue, we arrive at a specific motif for micro-engraving their personal seed. Afterward, participants can decide if they want to plant and document the development of the seed as a condition for getting it free of charge, or keep it as an artwork, in which case they opt to purchase it as a product.

Please describe the technical aspects of your micro-engraving process for our readers. I’m especially curious about the equipment you use!

Sergey Jivetin: Individual pieces of equipment, like the stereo microscope, the fine pneumatic engraver, and the jewelry micro-motor, are commercially available but their customization and integration into a mobile hospital cart makes this project unique. I also needed to design and manufacture a set of work-holding devices to accommodate a variety of seed sizes and shapes. The camera connected to the scope projects the live feed onto a large screen. In many cases, audience members appear mesmerized watching the seed being engraved.

What advice do you have for emerging and jewelry artists early in their careers who wish to nurture the conceptual aspects of their practice?

Sergey Jivetin: It’s good to know and address the history of the field, but I believe it’s just as important to draw inspiration for the work from outside jewelry, whether it be from contemporary art or culture, or life in general. And never stop questioning every aspect of what you’re making and how you’re thinking about it as well.

Who are some artists you admire?

Sergey Jivetin: Environmental art projects by Maya Lin, Tomás Saraceno, Andy Goldsworthy, Basia Irland, and Luke Stettner; objects by Tim Hawkinson and Peter Eudenbach; public sculpture by Aaron Stephan.

Tell us about some compelling media you’ve consumed lately, such as books, articles, or films.

Sergey Jivetin: My recent focus has been on the history of plant domestication and, in particular, its application in art. Green Light is a thoughtful book on the subject.

I’m currently reading Seedtime, a book I somehow manage to miss when doing my main research for Furrow. It was later recommended to me by a friend who is a farmer and a poet.

What’s next for you?

Sergey Jivetin: Taking the Furrow project on the road. The Hudson Valley Seed Company will host seed engraving sessions at the Philadelphia Flower Show next spring.

Later this year I will also be doing a performance engraving little furrows into topsoil to the rhythm of poetry at an organic farm in Delaware County in collaboration with the farmer and poet I mentioned.