Moniek Schrijer is a jeweler based in New Zealand. Having first trained in jewelry design and manufacturing, she then spent several years working in a metal arts foundry before obtaining her graduate diploma in jewelry and print making from Whitirea. She has been the 2015 Françoise van den Bosch Artist in Residence at Studio Rian de Jong, and was honored with the Herbert Hofmann prize this year for her pendant Tablet Of. Her current exhibition, Double Happiness, at The National, operates at the intersection of print and jewelry, transcending media, process, and scale. The show is accompanied by a catalog and an essay written by Sian van Dyk.

Katja Toporski: Your diploma is in jewelry and printmaking. Where does your interest in print making come from, and where do you see overlaps with the jewelry you make? I’m asking this especially since some of the work in Double Happiness is very graphic and two-dimensional.

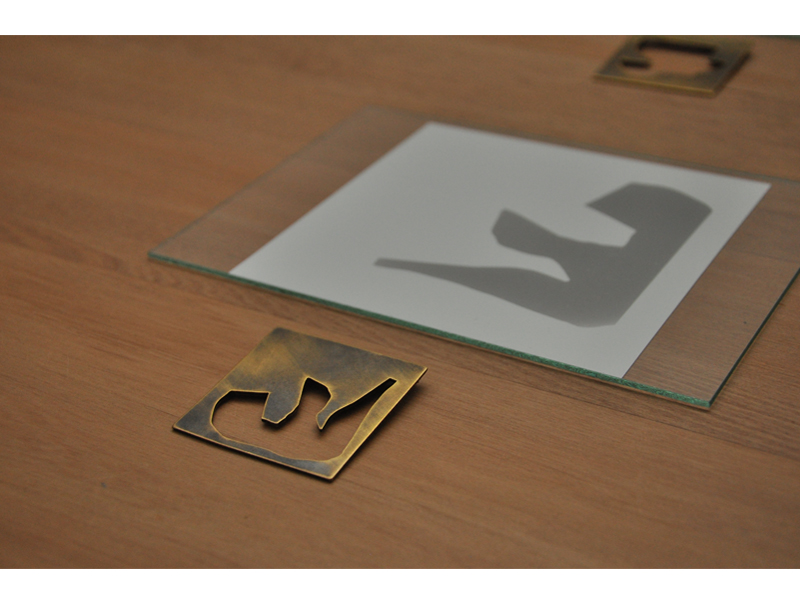

Moniek Schrijer: During my final year at Whitireia, I needed to a select a paper, so I elected to create a “special topic,” to invent my own paper, so to speak; the idea was to combine jewelry with traditional printmaking, printing etched metal and carved wood before they were further composed into adornment. It came to be because I was thinking about the crossover of skills, techniques, and process, particularly between printmakers and jewelers. Printmaking is quite heavy with its artist proofs and edition numbers … I distorted this, to take it to my own place by creating my own process. I treat the plate equal to the print: no editions … just one final print, and one jewel; they sit side by side. I like the duality, I like the synthesis, I like the conversation, and the souvenir.

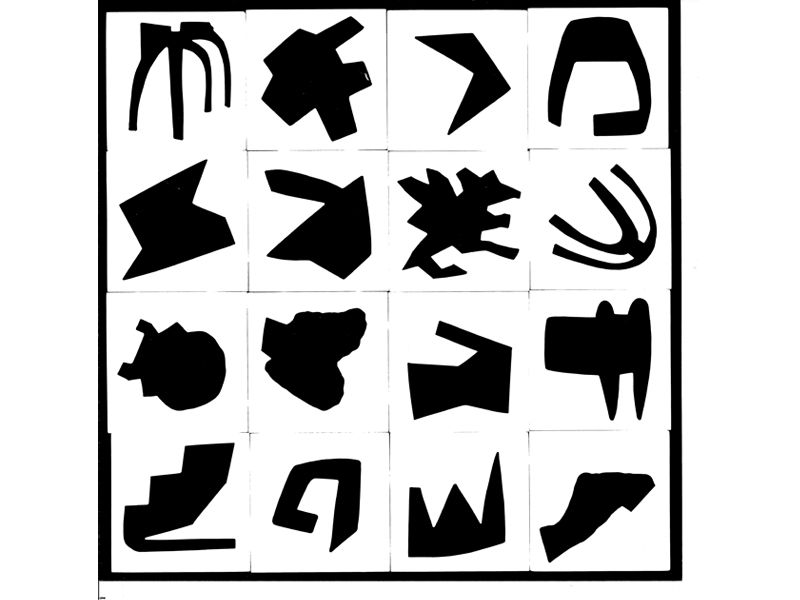

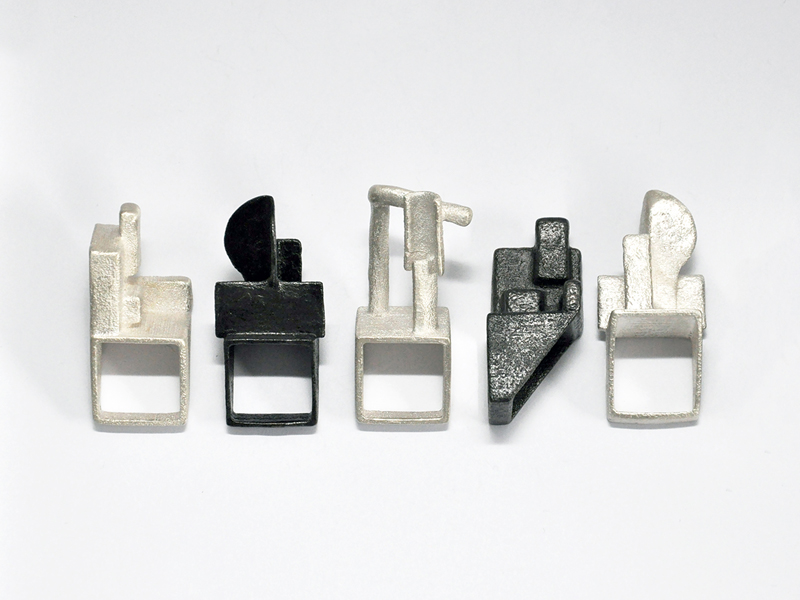

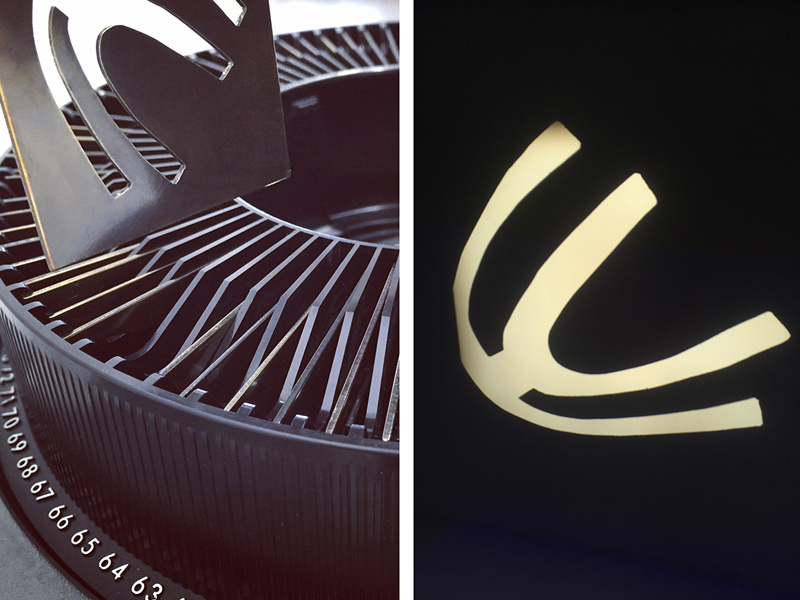

My exhibition Double Happiness is a continuation and an expansion on this, the two-dimensional being the pendant slides. Each slide has a corresponding photographic print, which I generated in a darkroom. The three-dimensional aspect consists of the sculptures which were scanned, scaled down, and 3D printed, creating a group of shrunken rings in silver and bronze.

Your work is very conceptual and driven by the symbolic power of the objects you work with. Do you have any favorite jewelry-making processes that you keep returning to, or do you consider process subservient to concept?

Moniek Schrijer: Concept and process occur concurrently. My making methodologies are in constant flux but also somehow resurface in a cyclical manner. I return to them and extend upon them, just as I return to materials and shift with them. Materials and objects have their own readings, histories, personal and cultural associations, all which support and fuel my thinking. Recently, and predominately within Double Happiness, I have reunited with the simple technique of piercing.

The exhibition includes a number of nonjewelry exhibits such as photograms, small sculpture, and a slide show (in which square pierced brass pendants serve as slides), all of which seemingly relate to one another. Can you talk about your creative process and explain how each informs the other in bringing together the show?

Moniek Schrijer: The creative approach alters depending on my desired outcome. If I am making a new thought, the sister to the work may not appear for a year, and there may be cousin in between. The elements in Double Happiness seemed to me quite disparate for a while. It was not until I abstracted and distilled my thinking, by going back to my workbook, examining my prime thoughts and sketches, that the works united and began to sing to one another.

The initial foundation of the exhibition was the projector and the square.

First the square appeared in the slide pendants leading to the square format of the correlating photographic prints. The square shape—again—of the black floating plinths, on which the three zinc-like sculptures sit, directed me toward the use of the square as the face or platform of the rings.

The jewelry pieces are composed of symbols that could be letters of a foreign language, or a short history of humanity as reduced to a number of basic shapes, like simulacra devoid of an original. Where do those symbols come from? They seem very enigmatic; does it matter whether viewers associate a specific meaning with them, or may they act as a blank slate, a place for projection, each viewer’s individual Rosetta Stone?

Moniek Schrijer: The symbols did have an original recognizable association, as I knew I would need a starting point to develop from. My aim was to denote an idea, quality, or state rather than a concrete object. In the course of making, this was fulfilled, with each of the 80 slides acquiring their own quality, directing the viewer to generate their own connections, as others’ interpretations of the work are essentially the most interesting part in art.

The new series of symbols, such as the piece that earned you the Hofmann prize in Munich, focuses on a fictional cultural obsolescence: You place invented characters into apparently anachronistic technological devices, like the slide projector with brass slides or the porcelain slate Tablet Of. Is your position on communication more romantic or nihilistic in nature?

Moniek Schrijer: The demise and imitation of technologic products form the basis of a small, slowly expanding group of works that have revealed themselves over the last five years: a series of diskettes covered in barnacles, set with jewels and shapes in aluminum; an oxidized brass credit card form riveted in ancient bronze coins; painted aluminum compact disk shapes possessing scratched barbed wire and tears; a mirrored glass brooch that is in the structure of a smart phone; right up to the tablet of porcelain slate, engraved with emojis and presently, in Double Happiness, cut-out brass slides, pendants, and brooches that have an uncanny link to Instagram… All of these technologies are examples of communication during my lifetime, devices that oscillate between different states.

The jewelry in your exhibition is embedded in the complex and indirect display setup you provide (slide show, etc.). How do you see the role of the individual piece after it has left the exhibition? Does it carry this context with it?

Moniek Schrijer: As the works depart, become divided and taken by owners into their new spaces, the individual pieces will take on their own narrative, just as all jewelry generally does. The works, I feel, will still contain their original essence, even though some of them—like the slides and shrunken rings—were part of a bigger picture once upon a time.

The slide pendants, once strung on silk and worn in the world, if held at the right angle in the sun, will continue to project light, emitting their unique hieroglyphics onto earth. The rings worn on the finger independent from their companion sculptures draw you into a bijou world of brutalist architecture and Eastern European monuments … so I reckon the pieces are safe on their own.

Your exhibition is titled Double Happiness. Could you explain the choice of title in the context of your work?

Moniek Schrijer: The title of the show did not take a linear path. I fought with many bleak ideas, as I found it extremely difficult to determine a title that captured the vibe of the work … but as deadlines loomed, something had to solidify… Double Happiness locked in… It was the double feature, the dual qualities of the slide and print, the sculpture and shrunken replica, traditional and futuristic, title discovered = happiness.

Do you have the next project brewing in the back of your head? Is there any topic you want to explore next, and is your direction toward more sculptural and installation work?

Moniek Schrijer: Crates of champagne full … no, there are a few things brewing, but nothing set in stone right now, as I need to resolve a motley mix that has been sitting on my desk and in my head so I can move forward … but as always the orientation is undetermined.

Where do you dream to be with your work in the future? Where is the perfect place for both of you?

Moniek Schrijer: I don’t expect to be in a perfect place … but I do dream … not really one to share my dreams… Here are a few thoughts … future wise… Collaboration with an artist/artists in different fields… Residencies, as they are such an excellent way to make and reflect … extend and deepen my knowledge/practice… Inspire others through guest workshops… Move into the fourth dimension… A solo show outside of New Zealand would be excellent, too.

Has anything you’ve recently seen/read/watched outside of the jewelry field moved you?

Moniek Schrijer: The spectacular New Zealand poet Hera Lindsay Bird.

Which artist do you admire, and why?

Moniek Schrijer: Another New Zealander, Jess Johnson. Her work is amazing.

Thank you!

INDEX IMAGE: Exhibition detail: projected Slides, Moniek Schrijer, Double Happiness, 2016, The National Christchurch, photo: The National