Known for his fondness for blending humor, found objects, and traditional craft, Kevin Hughes is an American studio artist who strives to make work with the form and depth of jazz. With an MFA from the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), Hughes has exhibited internationally, from Germany to Spain to Sweden. I talk with the artist about the inspiration behind his upcoming exhibition at Four in Sweden.

Olivia Shih: In the past, you’ve said that, “Art should be like a great jazz album—containing form, depth, emotion, rhythm, wit.” Do you have a background in music? If so, how does music inform your jewelry work? Do you think in terms of syncopation, bridges, and solos?

Kevin Hughes: I, unfortunately, have no education or talent in music, but have a great appreciation and admiration for music so, no, I wouldn’t say I really think in specific musical terms. I listen to a lot of music when I’m working—Miles Davis, Art Pepper, Chet Baker. I still remember the first jazz album I ever bought: Thelonious Monk’s Underground. I think my work, or at least the collection from Fickle Sonance, reflected the concepts of improvisation and rhythm though material, color, and form.

Could you give an example of jewelry art that is like a great jazz album and explain how it accomplishes “form, depth, emotion, rhythm, wit”?

Kevin Hughes: My goal for each collection of work is for it to feel like a great jazz album. Each song in the album is different but together they tell a complete story. I focus on each piece, but it is also important for me how they all sit together in the end—rhythm. Often the different materials in a piece feel like different instruments or musicians playing together—occasionally in harmony, occasionally clashing. And also I try to infuse a bit of wit and humor, but it’s always a bit understated, much like the wit and humor in the energy of jazz music.

How did you first meet the four cofounders of Four? And what was the joint process of putting this exhibition together like?

Kevin Hughes: I worked mostly with Karin Roy Andersson for the exhibition. Karin had seen my work before at Klimt02 in Barcelona, and we had met via Skype through a mutual friend. Afterward, I had sent her some images of work and it progressed from there. It has been great working with Karin and Four. She was very open to letting me explore this latest body of work. One of my favorite parts of putting together exhibitions is being able to meet gallerists, artists, and students. It’s always really fun and exciting.

The title of your exhibition, The Good Old Boys, recalls a golden age, tradition, and camaraderie among men. What inspired this nostalgic choice of title?

Kevin Hughes: I feel like there’s a lot of noise and excitement surrounding new materials and techniques. Often traditional materials and techniques are overlooked. But there’s a lot of really interesting things that can still happen with them and I was interested in exploring the possibilities. So for me the “good old boys” refers to that classic gentleman, traditional mentality—Marlon Brando, John Wayne—but also to the classic materials of metal and wood.

What does it mean to invoke male role models from the 50s in a profession that is engaging more and more with issues of gender roles? Gender in jewelry has been explored by a range of artists, from Iris Eichenberg to Jessica Calderwood to Vincent Pontillo-Verrastro.

Kevin Hughes: It’s really interesting, because I don’t really consider “gender” as an issue I explore in my work, but it’s something that has been questioned by a lot of people recently. I base my work on my interest, and my work is a direct reflection of my personality. I’ve always been really interested in the past, nostalgia, the cleaner more minimalistic style of the 50s, and more recently I’ve been very interested in that no-nonsense, no-bullshit mentality that I find personified in those male role models from the 50s. I’m pretty surprised about the questions about gender that arose from the concept of my show, and I really hope people aren’t looking at this work expecting some big statement about gender. Gender is such a big topic, and I admire the work of artists like Iris Eichenberg, etc., but it’s definitely not a direction I was exploring … at least not yet.

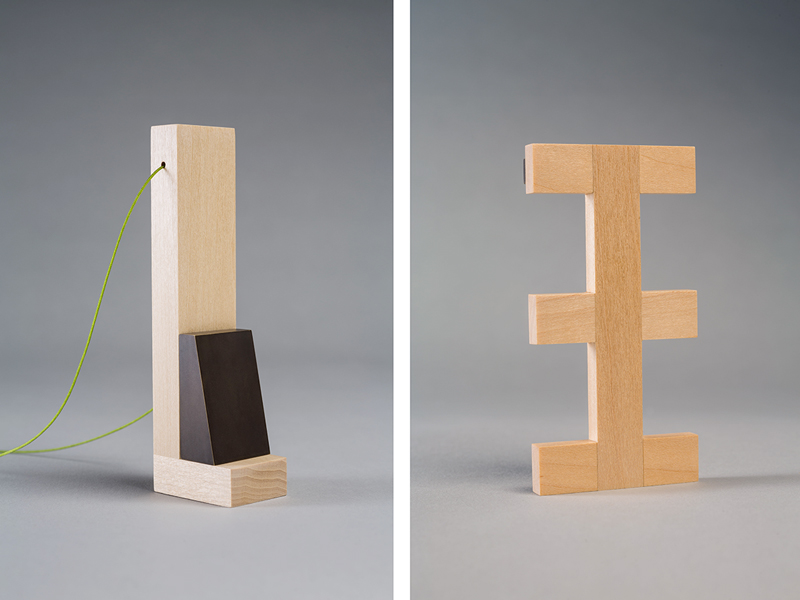

Another reference in this exhibition is the carpentry world of mortise and tenons. The works that mix wood and metal do so with a sober architect’s eye for construction and detail. Why the introduction of this “seriousness”?

Kevin Hughes: I wouldn’t necessarily consider this work as “serious.” In some of my past work I had explored a lot of difficult, serious concepts like fear, but for this collection I was more interested in craft and technique.

My father came from a position at Wedgwood fine china and porcelain in England to work at Lenox, here in the States. He’s retired now, but he was the director of 3D design. I spent a few summers working for him at Lenox while I was at Tyler School of Art. The work there is very traditional, to say the least, but the experience was very educational. During that time I also assisted Peter Handler, a furniture maker out of Philadelphia. All of the furniture was made of anodized aluminum and I learned a lot about joints, construction, machinery … it was all very precise.

They were, now that I think of it, a pretty solid group of “good old boys” themselves, who helped me hone in on a lot of skills and concepts in craftsmanship. I’ve always been interested in a lot of these traditional woodworking and architectural details.

But I think I met my most influential mentor at RISD. While I was there getting my graduate degree, I had the opportunity to assist Louis Mueller, who was the former head of the jewelry department. At that time, he was making large-scale metal sculptures. While my education at RISD really dove deep into concept, my work with Louis really helped me hone in on some technical skills that are really important in my work now. While I obviously gained a lot from my formal education, the chance I had to work with other artists and makers really helped me find my voice and perfect certain skills that I find really essential in my work.

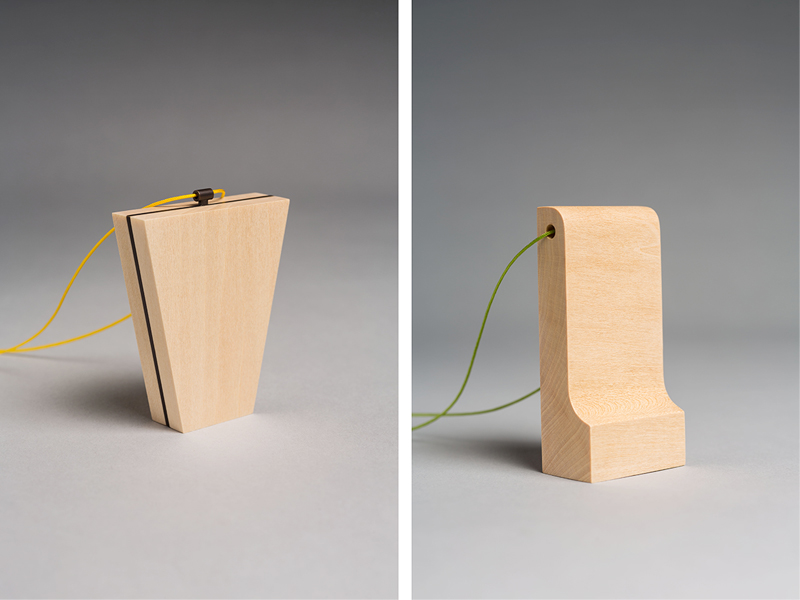

Your previous work blended traditional craft and materials with bold plastic additions. Are these colorful additions fabricated or found? Is it ever a struggle to reconcile these disparate elements?

Kevin Hughes: The plastic pieces in my previous work were all found objects that I’ve been collecting from toy stores, flea markets, and antique stores. The plastic’s artificial color and surface creates a conflict with the natural wood and metal, which I find really exciting. Although the work in my current exhibition is all metal and wood, I’m not sure I’m quite done working with plastic.

Humor often plays an essential role in your work. What do you think humor brings to jewelry?

Kevin Hughes: Humor plays an essential role in my life! It’s very easy to start to take yourself too seriously and your work too seriously. I want the viewer or wearer to have a good time with my work. I want people to smile when they see it. I also think that sometimes art can be a little inaccessible to a lot of people—a little too austere or exclusive. Humor gives art jewelry a bit of levity, which I believe helps connect it to the audience.

Could you describe a day in your studio for us?

Kevin Hughes: Usually I spend most evenings and weekends in my studio, which luckily is in my house. I just shut myself in, a cold beer, good music, and just focus. I’m a bit meticulous with my work, so I work slowly, one piece at a time, but I’m trying to change this and to work on multiple pieces at once.

You earned both your BFA and MFA in the United States, but you often exhibit in Europe and are represented by galleries in Sweden and Spain. How would you characterize art jewelry in the United States in relation to those in Europe?

Kevin Hughes: Although we only have a few galleries that are devoted to art jewelry, they are very energetic and enthusiastic about showing art jewelry. There are also a lot of interesting art fairs and events. Unfortunately, I think the general public is a little slow to appreciate art jewelry in the States in comparison to countries in Europe. But you can definitely see a shift happening, so I feel pretty positive about where we’ll be in the future. Also, we live in such a global online world right now, so the lines between the US, Europe, and Asia are all starting to blur.

Do you have any stimulating advice for emerging artists in the contemporary jewelry field?

Kevin Hughes: Your peers are one of the most valuable assets you can have. Keep in touch, compare work, compare experiences, share opportunities. Seek advice, talk about art, go see shows together. Just because you’re no longer in an academic setting doesn’t mean you can’t still have the same camaraderie and learning experiences.

Have you seen, heard, or read anything of interest recently?

Kevin Hughes: Lately I’ve been really interested in the work of Ron Nagle. There’s a lot of elements in his work—color, humor—that I find really intriguing.

Thank you.

The works in this exhibition are priced between US$500 and $2,000.

INDEX IMAGE: Kevin Hughes, Dovetail, 2016, pendant, black patina on brass, basswood, 30 x 15 x 90 mm, photo: Karen Phillipi