Aaron Decker: Julia Maria Künnap is an Estonian artist whose work I can only characterize with the word ‘wonder.’ Striving for perfection, she utilizes techniques that are time consuming, laborious, and intensely meticulous. Her work bridges the gap between the instantaneous and infinity, catching time like a snapshot in a material as eternal as stone. Not looking for words to describe her work, she hopes viewers see it in person, but not just see but look and let the work hit them at their core. Julia Maria Künnap is a graduate from the Estonian Academy of Arts and a practicing artist in Tallinn, Estonia.

Aaron Decker: Julia Maria Künnap is an Estonian artist whose work I can only characterize with the word ‘wonder.’ Striving for perfection, she utilizes techniques that are time consuming, laborious, and intensely meticulous. Her work bridges the gap between the instantaneous and infinity, catching time like a snapshot in a material as eternal as stone. Not looking for words to describe her work, she hopes viewers see it in person, but not just see but look and let the work hit them at their core. Julia Maria Künnap is a graduate from the Estonian Academy of Arts and a practicing artist in Tallinn, Estonia.

Aaron Decker: When did you start with jewelry?

Julia Maria Künnap: I remember making different kinds of tiny objects through all my childhood. During my initial studies when I was young, I learned to draw, paint, and sculpt in a Tallinn art school. I also attended some pre-courses at the Estonian Academy of Arts. During this time, I had to decide the department in which I wanted to study. I had never thought about it really, so I asked, ‘can I tell you tomorrow?’ (Laughs.) I was interested in three-dimensional art. I remember I was pretty good in sculpture. At the same time, sculpture seemed too abstract and too heavy. That is why I chose jewelry. When I made my decision, the secretary said, ‘ah, the metal department, then?’ Now they are calling it the jewelry department, but back then it was the metal department (by name, not by essence). I had thought that jewelry could be made out of anything.

So, what was your education like at the Estonian Academy of Arts?

Julia Maria Künnap: Well, I think it is a very good school, and that is the reason it was very interesting. I think the tasks we were given were often too complicated, but I’m glad that they were. To complete the tasks, you always had to jump higher, every time going further than the last. Now, more than 10 years later, I sometimes recall a situation and have a feeling that’s like…boom…now I get the point of some task or some teacher’s comment at a presentation. Back then, I didn’t get much of it. I was very slow in my personal development. In the beginning, many people try to please their teachers or their parents I think, but it was impossible to figure out how to please the teachers at the academy. I remember in my first year, after the presentations, I saw that the second and third year students weren’t making things technically well, but their work got a very good response. And I thought, ‘oh! I should try this. This is where the creativity is.’ And the following spring I made some ethnographic jewelry, a series of enameled tubes that were made really poorly. I got a 10 out of 10 points. (Laughs) Of course, things were not that simple, though I think some of the contemporary jewelers still think and work that way.

So, for creativity’s sake you worked like that?

Julia Maria Künnap: Yes, but the pieces were made in a way worse than I would usually make my work.

Interesting. Did you spend your whole education in Estonia?

Julia Maria Künnap: A bunch of our students had a co-project with Christer Jonsson. I had a discussion with him, and he said, ‘if you want to study at Konstfack, then just talk to Kadri and come to Stockholm.’ I was so shy. After a month or two, I told this to my fellow students and they convinced me to talk to our professor Kadri Mälk about this. So, I worked up the courage and asked Kadri. She said, ‘Hmmmm. Interesting. Let’s see after the presentations.’ And after the presentations she said, ‘ok, go.’ And I spent half a year at Konstfack. It was an interesting experience. It was very different.

Technically, I received a really good education there (at Konstfack). Bigger scale metal work, lets say. I learned how to weld and to use the lathe and milling machines. I have been using these skills a lot since then. At the same time, I didn’t have good contact with other students, with the creative side of the school, or with Sweden in general. It was very different, but a valuable experience. In our (Estonian) academy, the technical education was very good. We learned many old techniques, but somehow the jewelers’ focus was on smaller scale work.

And was Konstfack where you earned your masters?

Julia Maria Künnap: No, I did my masters in Estonia.

Then you spent some time afterwards at Alchimia?

Julia Maria Künnap: Yes. I got the Ruth Reisert-Hafner Stipendium and went to Alchimia to be the artist in residence.

So, how would you describe your work, aesthetically, conceptually?

Julia Maria Künnap: People ask about your work so often, don’t they? I am always asked, for example, is it wearable? And I say, ‘well, it depends on the wearer.’ A lot of ethnic jewelry doesn’t seem to be wearable, but people wear it every day.

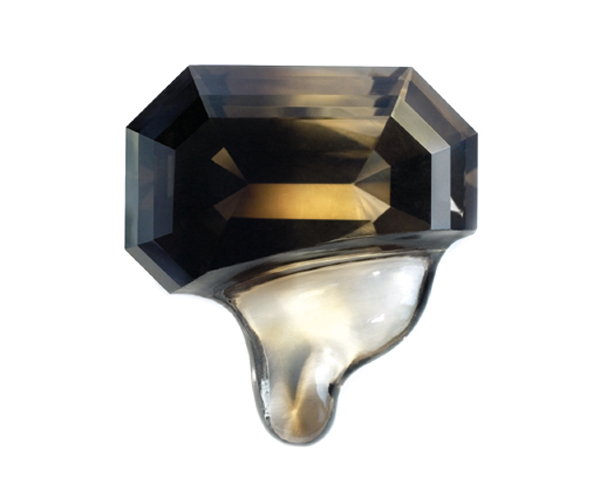

If I have to describe my jewelry, I would say, ‘if it is describable, it’s not worth making.’ So, you have to see it. Saying it’s made of smoky quartz and gold doesn’t say much about the work.

How would you describe your form language?

Julia Maria Künnap: I try to go toward simplicity in form. How can I say something with the smallest amount of words? It would be better to say something without words. That is where I try to reach.

Like reducing?

Julia Maria Künnap: Yes. Reducing is definitely important. I’d be so happy to reduce and even eliminate myself from my work. To become a medium.

For your process, where do you usually begin, and then where does it end? What is your process like?

Julia Maria Künnap: I start from vision. I am very lazy. (Laughs) So lazy. I want to make things that follow my vision. I wonder if it is worth bringing to life. Will the result be interesting enough to look at? Would it be attractive to me? This is where it usually starts. As I work, I go through different materials and different forms. I can say that I am not scared of any technical difficulties. If the idea is interesting enough, I just find a way to do it. I start working.

Instead of planning, are you more of an intuitive worker?

Julia Maria Künnap: I try to be. There is so much of this ’intelligent’ art, which is often a kind of mathematical equation. You have a task, a problem, and you solve it. You put the description on the wall, and you see these mathematical formulas. If I want to experience the beauty of mathematical formulas, I look at an equation. There’s so much beauty in them, too. For example, I could listen to my father talking about the mathematical constant E for hours. Art is meant for other organs than just the brain. You should be able to touch it, feel it, and sense it.

So, more along the emotional and the physical connection rather than just the intellectual connection?

Julia Maria Künnap: It should go straight to your heart and your spine—to your body without the brain. You shouldn’t need a written explanation.

Julia Maria Künnap: Unfortunately, I’ve seen it too much. And not just in jewelry, but in all fields of art. I think it has some Anglo-American roots. If you are taught to make a research book every time you get a task in a college, and the thicker the book, the better the research and therefore the result—full of continuity and cause-and-effect nightmare—it might be a good way of documenting a process and a good way to evaluate students and their amount of work, but it has to be got over one day. If you use the same pattern of research, you get the same kinds of results. If you take the same path, you reach the same place. The results of this type of work are a bit boring.

I think what you are getting at is that art is not a straight line, not equational, but more complex and often unexplainable. Is that correct?

Julia Maria Künnap: Even this complex system, this grabbing from here and there, is very commonly used. The book of research I described before is usually full of fragments. I try to avoid this way of working. I am more interested in the idea that comes in a short period of time, not really something thought through with intense pressure, but if you are ready for it, it comes to you in a flash! That is the work I admire, and how I try to work myself. The methods I use in making jewelry are slow. From one moment on, an idea has so many ways to be developed, so many outputs and options. You can never do them all. You do some, and then you have something new that comes to mind. Each rises out of each other.

From where did your more recent work develop, or was it just your basic interest in stone carving?

Julia Maria Künnap: Crystals are so beautiful. I feel guilty every time I start powdering them, but I try to give the stones qualities that they never had. For example the quartz can never be melted like I force it to be. So that was the idea. It is undercutting what the stone actually is—solid but appears to be liquid.

Can you comment on the juxtaposition of the facets with the parts that appear melted or in liquid form?

Julia Maria Künnap: There is a large contrast in many ways. The stones cannot melt like this. The drop could not freeze like this. Even if you could melt quartz, it would be so wrong. Gems just don’t melt. Glass does. It is trying to capture a moment in something so eternal as stone.

I would definitely say that your work looks like a snapshot, capturing the moment!

Julia Maria Künnap: One piece I have appears to be a faceted gem splashing like water. This is definitely something that draws me to work, this visual metaphor.

Do you think there is a strong Estonian influence in your work?

Julia Maria Künnap: I feel it more in how I think. I have made many decisions to avoid a visual language that is already present, especially next to you. There is no point in copying someone big or famous. You need your own language, and developing that requires time and a clear mind. That is why I think many works that seem to be visually distant actually could be very close in mentality and vice versa.

Do you think there is a strong Estonian mentality and aesthetic?

Julia Maria Künnap: Yes! I think the visual language has quite a large variety, but there is something that unites us, and I think that is the spirit. Maybe the school does unify us, because there is only one school to learn jewelry here. We have been taught not to become like others. We are not influenced that much by the international mainstream. Estonia is still a distant forest in the north. One thing that does influence us is the internet, which gives you all the information you need and even more. The other thing is to walk down the street in the city every day. We are like wild animals here, and I like it. It seems our jewelers have survived ‘Euro-fication’ now. Also, Estonian contemporary jewelry is not that commercialized because we don’t have a strong market for it here. There are good opportunities for artists to get support from the Cultural Endowment for exhibitions, and it is widely used.

I have observed that air of freedom here. You are really going for your vision. That comes first.

Julia Maria Künnap: Yes. That’s how we were brought up.

What do you think of the work of jewelers just coming up?

Julia Maria Künnap: Estonian or international?

Either.

Julia Maria Künnap: I see new possibilities in the work because of updated technology, and that (technology) has not unsharpened the young brains. The works I’ve seen from younger people are very interesting. I see a lot of figurative elements. One of the reasons young artists like them is just due to the time period—the pendulum swings back and forth—but it also happens due to our good old-fashioned fine art background. These artists still know how to draw and how to sculpt.

In the world in general, I hope this period in art—when artists make things everybody could make—is coming to an end. I mean, readymade scrap badly glued together forming a potato-shaped object as a result. The same thing is happening in knitting, for example. My grandmother was a professional knitter, technically very talented, and she taught me how to knit. Most of the knitting I see exhibited is so bad. You can tell it’s the first time the artist has held the needles. It is not interesting, especially when everyone can see (via the internet, for example) that there is a parallel world of great craftsmen and craftswomen who make miracles, but their paths rarely cross with the art world.

What are some of your inspirations, or what are you inspired by?

Julia Maria Künnap: I am inspired by imperfection.

Imperfection?

Julia Maria Künnap: Yes.

Can you talk more about that?

Julia Maria Künnap: It is a strong source of motivation. If I see a perfect thing—an artwork, a poem—I just breathe in and breathe out. It just comes and then goes. But if I see something that irritates me, I start analyzing. Why am I irritated? Why isn’t it perfect? Where is the ‘mistake’ made? Usually, once I have deconstructed the whole piece in my mind, I already have so many good ideas. In the end, these ideas don’t have much to do with the source of inspiration.

Well, Julia, thank you very much for your interview. I really enjoyed your work. It was extremely fascinating.

Julia Maria Künnap: Thank you!