Sham Patwardhan Joshi is a contemporary jeweler from Pune, India, who moved to Germany in 1987, at the age of 23. Joshi studied jewelry at Hildesheim, under Professor Georg Dobler. His works have been shown at several international exhibitions, including Schmuck, in Munich.

Project Bawra: How and when did you arrive at making jewelry?

Sham Patwardhan Joshi: It started as a hobby. Around 2002, I wanted to make a traditional necklace of 17th-century Shivaji coins that I owned (editor’s note: Shivaji was an Indian warrior king). I made this at a goldsmith’s studio in Bielefeld. This is where I learned jewelry basics, which were later useful in applying for jewelry school. At the time, I was a freelance interpreter in Germany, working for Indian companies in the leather and automotive industries. Due to economic shifts, the market for my services was declining. So I applied to Hildesheim. I was 42 and the oldest student in class.

What’s your current employment?

Sham Patwardhan Joshi: I teach casting for the experimental jewelry program in Hildesheim, which is for students from all other faculties. Working at the university allows me to explore my ideas, in terms of a place to make work and also financially.

What do you find challenging as a contemporary jeweler trained and living in Germany?

Sham Patwardhan Joshi: To establish one’s place and stay relevant. Contemporary jewelry doesn’t have a wide market, and in Germany it’s concentrated around Munich and Hamburg. Activities and exhibitions are centered in Munich. One has to constantly present work through exhibitions and competitions. On the level of making, the real challenge is to make work that’s in harmony with itself. The maker needs to feel that the work is complete, and with that comes satisfaction.

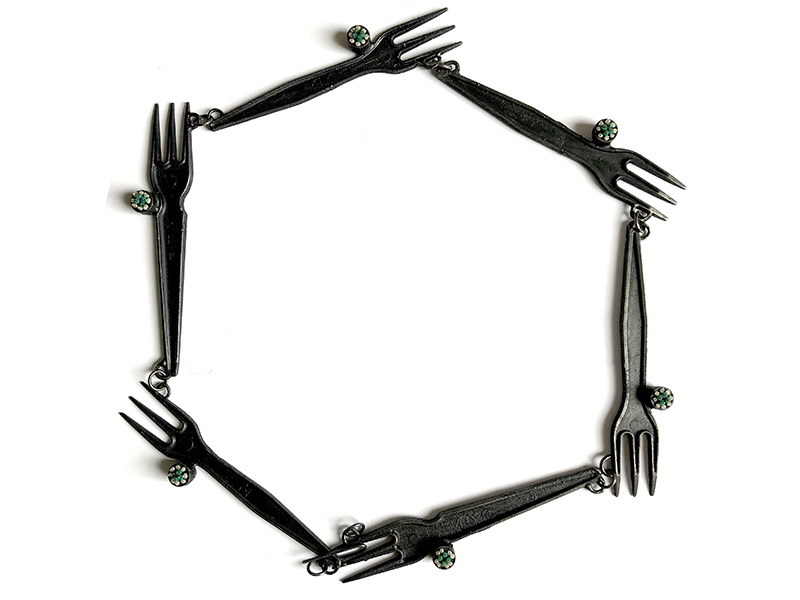

You love to cook elaborate Indian food. Can you talk about your relationship with food and cooking?

Sham Patwardhan Joshi: In Germany, as a vegetarian I cook my own food. But I’ve been cooking since the age of 14. I consider Indian cooking an ancestral gift. The kitchen is extremely refined. It’s a treat to the senses because every ingredient’s effect on the body, mind and spirit has been studied in detail. For me, its a form of active meditation. I think I’m as good as professional. Recently, I was visiting my nephew in England and we felt like celebrating Diwali (an Indian festival) so we cooked many Indian delicacies—chidwa, laddoo, namak pare.

You’ve been posting a lot of drawings/paintings on Instagram. Is drawing vital to your process?

Sham Patwardhan Joshi: It’s a tool for relaxation. Ideas only present at that time. Jewelry and drawing are two different approaches to express myself in a given moment. Both are process-oriented for me.

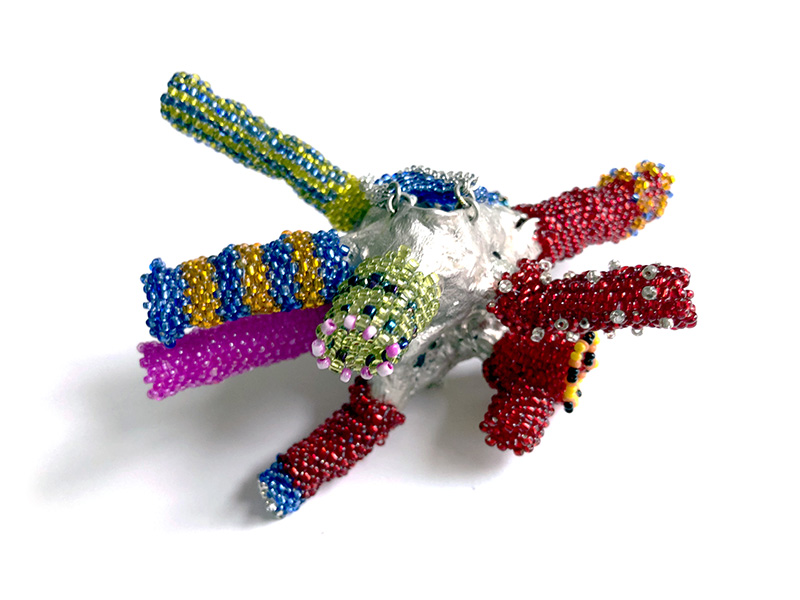

Please talk about the Hands series.

Sham Patwardhan Joshi: I started making hands in 2007–2008 and saw some potential. This series, one can say, is my life’s work and I still don’t see an end to it. I use my hands to mold the wax and the hands shape themselves in the process of making. These hands use my hands as a medium to shape themselves. This is why I call them Thinking Hands.

Tell us a bit about your process and the amount of time spent making at the bench.

Sham Patwardhan Joshi: On average, six hours a day. I’m not worried about whether people will like what I make. I do what I like.

What does preciousness mean to you?

Sham Patwardhan Joshi: In Pune, I found ID photographs thrown on the street as garbage. I picked them all up and made a necklace. I felt the photographs were precious even though they were discarded. It won the Mayor’s prize at Legnica, Poland, in 2016, when “City” was the exhibition theme. One has to have heightened sensitivity toward objects and their associations. Yesterday, I found four flower petals at four different spots.

Do you wear any jewelry yourself?

Sham Patwardhan Joshi: I exchange pieces with other jewelers and wear those when I’m going out.

Have you shown/attempted to show your work in India? What response have you received?

Sham Patwardhan Joshi: My works were shown twice in India in group exhibitions. The first was a show in the lobby of the Hyatt Hotel, Pune, in 2012. Pune is currently an upcoming cosmopolitan town in the state of Maharashtra, in India’s midwest. I organized the show, which focused on contemporary jewelry design, with the Goethe Institut. It presented three major European designers: Georg Dobler, Esther Brinkmann, and Margit Jeschke. As part of the Indo-German cultural collaboration, my work was also shown, albeit in a smaller capacity.

Mostly hotel guests saw the work. A famous fine jeweler in Pune sponsored the catalog. The Goethe Institut hired curator Raju Sutar, a local artist and owner of a modern art gallery, for publicity and local partnerships. As part of the exhibition program, I also did jewelry-design workshops with fashion students at the School of Fashion Technology. I really enjoyed it since the concept of contemporary jewelry was new to them. Some of the students had really interesting ideas and were open-minded.

The second occasion was an exhibition called Adorning, organized by Apparao Gallery, in New Delhi, in 2015. This was the first attempt at showing cutting edge works in the field of jewelry by Indian makers. Works by 15 artists/designers from across the country were presented.

What was your experience of the Adorning exhibition?

Sham Patwardhan Joshi: It was a genuine experiment, but a framework for understanding contemporary jewelry still has to be built in India.

You come from a culture with a very strong and distinct language of ornamentation and adornment, often traditional and heavily decorative. How do you negotiate this in your practice as a contemporary jeweler in Germany?

Sham Patwardhan Joshi: In German one says weniger ist mehr—less is more. To come to this adjustment in jewelry is important and difficult. Sometimes I create pieces in complete opposition to this. A studied eye will always see the connection to my Indian origin. I’ve lived here too long for the traditional image of jewelry to strongly resonate in my mind.

There’s been a lot of excitement about new jewelry in India in the past few years. Many new designers have been experimenting with nonprecious metals/materials and various crafts to give them new expression. But most of the jewelry, even “contemporary,” is being made by craftsmen who do not design it but are doing a job they’ve been assigned. Designer and maker are different people, resulting in derivations with confused authorship. I feel having so many craftsmen to do the “laborious” job of making (often seen as a blessing) is stopping the designers from getting their own hands dirty and producing original work.

Sham Patwardhan Joshi: This is a quest for money. Everyone has the right to earn money. For craftsmen, it’s modern slavery.

On the other hand, many rural craftsmen need work and a market to be able to keep practicing their craft. One of the figures seen as responsible for providing this is the designer. What are your thoughts on this?

Sham Patwardhan Joshi: This is not a problem that can be dealt with immediately. It’s the government’s job to deal with this.

Isn’t it true that the traditional jewelry maker in India has been male? Nowadays, you see mostly female students in jewelry schools. What do you think about this shift?

Sham Patwardhan Joshi: It’s the general perception that after becoming a designer, women could pursue the profession on the side while having a family. To me, the whole thing lacks seriousness.

The exquisite Mughal jewelry was designed and produced by master craftsmen. Do you think its still possible for Indian craftsmen to possess and demonstrate similar caliber, given a chance to design from a free mind?

Sham Patwardhan Joshi: Given a chance, an artist (not just an artisan) will pick up very fast and show their creativity.

Are you hopeful for more democratic jewelry coming out of India?

Sham Patwardhan Joshi: I feel we will not experience a wide change in our lifetime.

That’s a grim picture!

Sham Patwardhan Joshi: … (grin)