Paula is an active promoter of contemporary jewelry, bringing new and diverse tendencies, aesthetics, and artists together to Portugal in a special and very individual bouquet. A lady of fierce gaze and warm heart, she’s a manager, a teacher, a counselor, and a friend to the artists she takes under her wing, never shy of a sharp comment or a warm welcome. This interview is but a glimpse of the reasons, passions, and dreams that made it all real.

Manuel Vilhena: Tell us about your first meeting with contemporary jewelry. What fascinated you about it?

Paula Crespo: There was indeed a meeting, but I doubt that it was with what today we call contemporary jewelry. It came in the form of a pamphlet, which appeared at the school where I was teaching at the time, about a jewelry contest in Oporto, that would awaken passions buried long before…

This fascination had been felt when I took up my first pencils, when I swept paper with my first brushes, or when I mixed the first paints. After that, when I used the first pliers and dared to dismantle my mother’s necklaces and redo them at my own pleasure.

Shortly after, I enrolled in the jewelry course at AR.CO (the art school in Lisbon), where I did my jewelry studies and where I would later teach for a short time. AR.CO at that time was a small but very dynamic school. It was the 80s, known for their effervescence not only in political but also in social and cultural terms. After 40 years of dictatorship and isolation, the “Carnation Revolution,” in 1974, brought us back to freedom and opened the doors to the world. The jewelry course essentially valued the technical preparation of the students, but there was already an awareness that training at a conceptual and artistic level was necessary and desirable.

It was in this context that Thomas Gentille’s workshop took place, a remarkable and inspiring experience for everyone who had the privilege of attending it, like me. For the first time we discovered the possibilities of new materials—Formica, aluminum, steel, titanium—and new techniques such as anodizing that allowed us to color metals. It was a small revolution and I think the beginning of a new era for that generation of jewelers. Nobody wanted to work with the traditional metals that had hitherto been the basis of all our learning anymore. A world of possibilities opened up that everyone wanted to experience.

In addition to the workshop, Gentille’s exhibition at the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, held at the same time, was also a reference memory that accompanied me on my journey as a jeweler. How was it possible that in that cold geometry, in that total absence of adornment, there was so much poetry? Now I was beginning to understand what artist jewelry, or contemporary jewelry, was. These were decisive years that radically changed the direction of my life up until today.

Your gallery just turned 21 years old. What triggered your dedication to your work as a gallerist, and what has kept you active for so many years?

Paula Crespo: The gallery is a scenic space in constant change and evolution. There, stories are told and delightful secrets are revealed. And every day I’m surprised by what I see and what I discover through the hands of my dear artists. So I would say that what keeps me active is enchantment.

Also the friendships that I have been making over these long years with artists to whom I owe the greatest gratitude and recognition. Less important, but definitely more dangerous, maybe my stubbornness, determination, obstinacy. Finally, the conviction that what I do, I do well.

Do you consider your gallery as your “work of art”?

Paula Crespo: I never thought of it in those terms, but you might be right. Despite knowing that “my work of art” is not, nor will it ever be, complete. But I don’t dislike that either, and maybe that’s one more reason to continue.

I think I’ve fulfilled several aspirations in this space. Those buried passions I mentioned before—arts in general and architecture in particular were part of my family universe and perhaps that’s why spaces affect me so much, both positively and negatively. I was born and raised, and have always lived, in Lisbon. The city was my natural habitat and it was in the city that I found my references and shaped my tastes. The Guggenheim Museum or the Cathedral of Chartres impress me almost as much as a beautiful landscape. Like my father and brother, I wanted to follow architecture, but for various reasons this didn’t happen. This past is certainly reflected in my work and my love for designing and crafting, be it objects, jewels, or displays that value and highlight them.

Do you think there have been marked changes in the way artists work and how they define what contemporary jewelry is throughout your years as a gallery owner? Could you elaborate on some of these changes?

Paula Crespo: Yes, the world has changed and contemporary jewelry has inevitably changed with it. It has consolidated itself, asserted itself as an independent discipline, and expresses itself in total freedom, contrary to the idea of those who would eventually like to see it confined to more consensual aesthetic standards.

Each artist seeks her/his particular form of expression according to her/his personality, her/his training, her/his references. The approaches are endless and encompass countless proposals ranging from the single piece, with higher value, to the small series that nowadays satisfy a wider audience with eventual less economic capacity.

At the national level, I would say that artists are more informed and more demanding. They’re also more professional, closer to international standards, and this is very positive. Foreign artists are very accustomed to working with galleries, they work hard, they’re organized, they meet deadlines, they renew work, they propose exhibitions, there’s an exchange of services that flows and facilitates work, with benefits for both parties. We’re starting to see that in Portuguese artists as well.

The world and society have undergone great changes in the last two decades, especially with regard to how technological development is changing the ways we communicate with each other. Do you see these changes reflected in the artists’ work? Does this affect your work as a gallery owner?

Paula Crespo: Yes and no. Not all artists have entered the “wave” of globalization. Many work outside of it, if not against it.

I’m reminded of you, of course. Your work is clearly a good example of contemporary jewelry made with ancestral techniques, carved wood and bones dyed with natural pigments, iron, gold, and some precious stones, with little or no soldering. And from this scarcity of resources you build a beautiful universe that in fact takes us back to the beginnings of jewelry for the fetish, the alchemy, the protective jewelry idea, the talisman.

Others used it positively and took advantage of it. Obviously the results are different, but not necessarily better or worse than the others. As a gallery owner, it’s very interesting to see these different perspectives that sometimes translate into different values and capture different types of audiences. Or not. Because good technology combined with excellent design and execution also comes at a high cost.

Perhaps Melanie Isverding is a good example of someone whose work is largely done with high technology, but because it’s extraordinarily well designed and finished by hand, it has the surprising result that we know. Powerful pieces of great technical complexity that would never be possible to make just by hand.

It’s not easy for a contemporary jeweler to live exclusively from the sale of his/her work. Is the motivation of artists in that direction also part of your work? If so, what do you do so this can happen?

Paula Crespo: Obviously, yes. The best motivation is to sell work. This is what most encourages artists and compels them to continue. Therefore, the importance of knowing how to sell this type of “product,” which is different and has its own specificity. For this reason, there’s also a need for jewelry galleries with specialized personnel who know not only how to talk about the works and the artists, but even how to handle the pieces without damaging them. This seems obvious, but it isn’t, and the artists know it and show great respect for the ones who do.

Giving an artist the opportunity to participate in collective or individual exhibitions is also a big stimulus for the artist, who then feels impelled to invest more in her/his work. The experience of public exhibition brings, in most cases, a step forward in the work of artists. That’s why we hold regular exhibitions, not only of artists from the gallery but of new and young artists. In this sense, we have also created the “window project,” a vitrine intended to show small projects, for those artists who want to present new work that doesn’t yet fulfill the requirements of an individual exhibition.

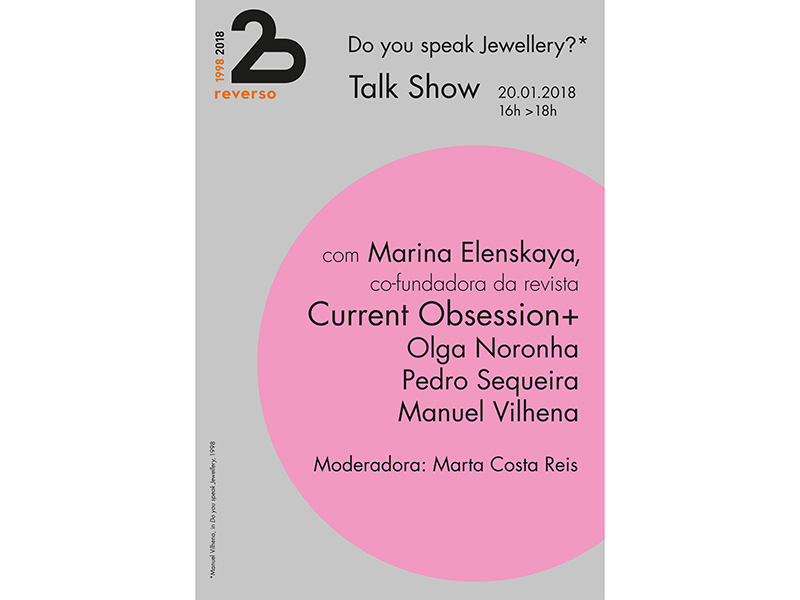

No less important is the meeting between artists that Reverso promotes during the international exhibitions it organizes. As a result of these events, cooperative work has developed between Reverso and other institutions such as AR.CO and PIN (the Association of Contemporary Portuguese Jewelry), resulting in several workshops and lectures and even the exchange of inter-school projects, such as one, a few years ago, between AR.CO and the Kunsthochschule of Halle, Germany.

Finally, a simple dialogue about the artist’s work can also be very effective and motivating, and I always do this with great pleasure. It’s my pedagogical side, which has stayed with me from the times when I was a teacher, and which has to do with me, too, with the pleasure I have in sharing with others experiences that are gratifying to me. And I know that my taste, which is genuine, is also contagious, and this is reflected both in customer service and in student and teacher study visits. So, for me, an added pleasure.

In the arts, in general, there’s been a shift to more conceptual paradigms of artistic execution, often dismissing manufacture to a place without prominence. Do you think that a good piece of contemporary jewelry can be made without technical mastery?

Paula Crespo: My first impulse is to answer NO. Emphatically NO.

Obviously, good technique alone does not make a good piece, but it is the necessary support, and not necessarily visible, of a good piece. It’s true that some artists use a language that apparently doesn’t need refined technique, but when the piece is good, some hint of technical mastery, however hidden, has to be present. Because when we talk about jewelry techniques, we’re thinking about traditional jewelry techniques, right? But there are many other techniques that you or I probably don’t know and that today are applied to jewelry. Crochet, for example, by Felieke van der Leest; paper folding by Nel Linssen; Ela Bauer’s mastery of latex; and many others. Apart from these cases, there may be exceptions that confirm the rule, but I have some difficulty in recognizing them.

How do your customers perceive jewelry that doesn’t require classical technical bravery? What are they willing to pay for?

Paula Crespo: Contrary to what one might think, customers, even those supposedly more “illiterate” in this area, have a very acute perception of the quality/price ratio. This is the fundamental axis and the first level in the appreciation of a piece. It’s also true that this “quality” essentially values materials and technique. The conceptual paradigms to which you refer are only perceptible by a more restricted and demanding audience, in which collectors are obviously included. This is where an important and perhaps the most challenging part of the gallery’s work comes in—the dialogue with the client about the artist’s work process, his/her path, his/her identity marks, possibly the context in which his/her work is inserted in the contemporary jewelry scenario. In other words, to make the artist’s work known in a consistent way, with information and knowledge. This requires the dealer to enjoy the work s/he does and especially what s/he is selling. There are many, many hours of hard work, the fruits of which, sometimes, are only seen much later.

But answering your question directly: What are customers willing to pay for pieces that do not require such technical bravery? They’re not willing to pay much, it’s true. This is the case, for example, in 3D-printed works. I think that for most buyers the value of the material has been partly exceeded, perhaps because the price of so-called noble materials has become inaccessible to many. But there has to be mystery not only in the concept but also in the technique, be it that of paper, plastic, resin, or silicone. The charm of the piece will eventually be in this juxtaposition of surprise and mystery, and the price has to be consequent with that, whatever “that” may be.

Could you share with AJF readers something interesting that you’ve seen, read, or heard recently?

Paula Crespo: I’m currently reading Jewellery in Context: A Multidisciplinary Framework for the Study of Jewellery, Marjan Unger’s magnificent PhD thesis, defended in 2010 and now translated into English by Theo Smeets and edited by Arnoldsche. This book was a kind gift from Jantje Fleischhut on the occasion of the NCDG (New Craft Object Design in Lisbon) expo at Reverso, last November. An excellent softcover edition, pocket-book format, because the book is really meant to follow you around, to be read leisurely, with time, to be underlined with a 2B pencil—for those who like to do it as I do. An essential work for all scholars and lovers of jewelry.

We started this interview with a look to the past. I’d like to end by directing attention to the future. If you could create/carry out a project—with unlimited resources—what would it be?

Paula Crespo: What would they be… Firstly, to organize a jewelry biennale in Lisbon. It’s a city flooded with light and culture and gastronomy… our jewelry heritage is rich in both classical and contemporary terms, and the plethora of museums and galleries would serve as the perfect background for such an event.

Secondly, to participate in fairs like Schmuck or Collect. Finally… to exhibit at Reverso all the artists I love, and much more that doesn’t fit here.