Karen Smith is the founder of We Wield the Hammer (WWTH), a program that teaches the fundamentals of metalsmithing using copper, brass, and sterling silver to young girls and women of African descent who might not otherwise consider a career in this field. WWTH offers an opportunity for artistic equity, economic empowerment, and access to a vocation that is, worldwide, traditionally unavailable to women. The program is free to students, and Smith is working to build the nonprofit, moving it to a new location and restarting classes early in 2021. Smith lives in Oakland, CA, but envisions taking the program to other cities and countries.

WWTH came out of two apprenticeships that Smith created for herself in Senegal in 2018 and 2019. What follows is a heavily edited version of a conversation via Zoom. We’ll start by talking about WWTH, then circle back to Smith’s time in Senegal.

Nathalie Mornu: Tell us about We Wield the Hammer.

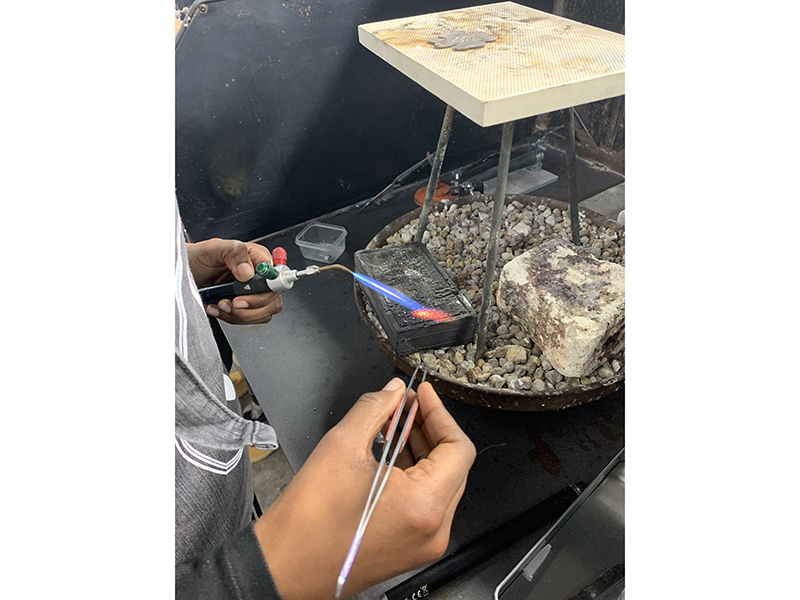

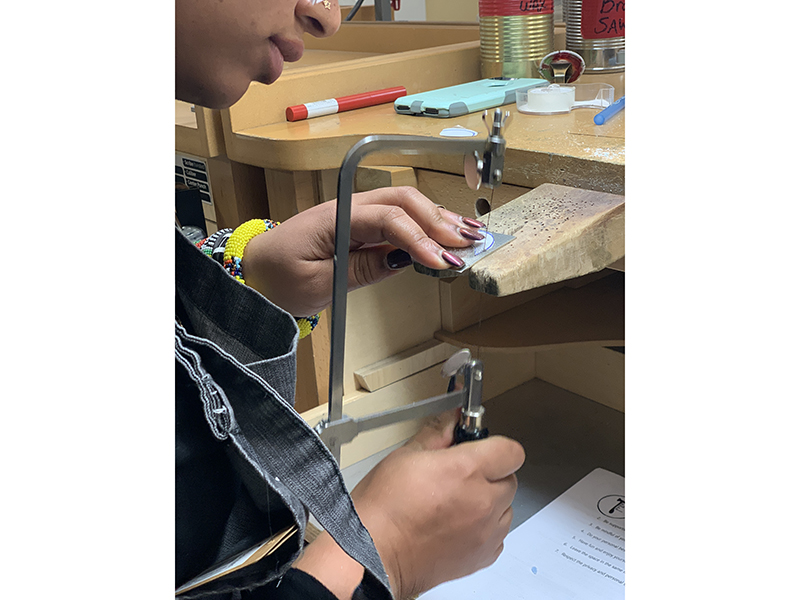

Karen Smith: We Wield the Hammer teaches the fundamentals of metalsmithing fabrication using precious metals. It’s a training program, with a focus on teaching skills and not on creating particular items. I was talking to somebody recently and as she spoke, it was clear that she thought WWTH was a series of workshops. It’s not. It’s not about coming out with a perfect ring. This is an eight-week program; students emerge understanding how to use the saw, how to use a hammer, how to use a torch and control heat, what sweat soldering is, how to solder well, and more.

When a young woman completes this program, she can go on to a formal apprenticeship with a jeweler and become a jeweler. Or she can apply her skills in a different way, creating small sculpture, for instance. She might even leave this program and open her own business.

This program gives women an access point. It’s very difficult to learn this practice without access, without money. That’s why the program is free. That’s why my answer to “how can we help?” is, “WWTH needs money.” Our projected annual budget for 2021 is $300,000. That includes a salary for me, that includes a studio manager. And every time I say that, I hear, “That’s not a lot of money at all.” Except nobody’s written me a check for that amount!

I aspire to share what I know. I aspire to help women and girls come into their own best selves. I aspire to offer alternatives to marginalized girls and women who may not know that there are alternatives to what’s in their neighborhoods.

WWTH came out of your time apprenticing in Senegal.

Karen Smith: Yes. I was inspired working in the shop in Dakar. One little girl used to watch me in the workshop there all the time. She came by nearly every day, and she would watch, but would never speak to me. I would say hello: hello in Arabic, in French, in Wolof, and even sometimes in English. And she would never reply. One day I asked my teacher’s son why she wouldn’t talk to me. He said, “Because she thinks you’re a ghost.” “How can she think I’m a ghost?” He replied that she’d never seen a woman with a hammer and a torch. “It’s only you that she sees.” That exchange was my inspiration.

When I was in third grade, to my delight, my teacher read a Black author during story time—The Best of Simple, by Langston Hughes. It was my first Black writer; that’s when I knew I could be a writer. I knew I could write books because here was a book written by a Black person, about Black people, with Black people on the cover. Representation is everything!

And so I understood—now that this kid in Dakar has seen a woman doing something she never saw a woman do before, she knows that it’s a possibility for her. Who’s going to teach her if she decides this is her path? And that’s how We Wield the Hammer was born. It was born out of my recognition that women should have access to this vocation, and when they—women in Senegal, as well as women elsewhere—can have access to this vocation, it can change their lives. I don’t live in Senegal. I currently live in Oakland so I began the program here. It incubated in 2019 and has four sessions per year. Until the shutdown from COVID, we were located at the Crucible, an industrial arts school in West Oakland where I’m a faculty member in the jewelry department. I’m looking for our own space where we can have as many sessions, as many open studios, as many opportunities as we can allow.

So at WWTH, a young woman who may never have encountered someone in her community who makes jewelry, and who therefore may not have considered it as a path forward, has the opportunity to try her hand at metalsmithing.

Karen Smith: We’re in a profession that’s pretty highbrow. The cost of metal and tools alone takes it out of the realm of the everyday. I personally find it a pretty exclusive occupation, which means marginalized—and I count myself as marginalized—people have been taken out of the equation.

Did you know that Oakland has the highest incidence in the US of young women who have been trafficked? When someone has gone through the trauma of being sexually trafficked, everything about their life changes. It’s not like you’re going to go back to high school and then on to college and become a doctor. That can happen, but that’s an extraordinary circumstance. The futures of a lot of young women are impacted by this awful thing. A lot of them fall into early single parenthood, they fall into a poverty-filled existence.

And it’s not just these young women—it’s young women who don’t complete high school, or who don’t go to college. Young women who come from working-class backgrounds. It creates this thing that we understand as the feminization of poverty. Poverty impacts and affects women, which impacts their children, which impacts and affects their communities. But there are ways to offer alternatives, there are ways to give people access to skilled work, and that way forward is not always formal education.

However, metalsmithing or access to the jewelry industry has not historically been a way forward. It has not been an access point. The catalyst for WWTH was watching the exclusion of women from this profession in Senegal; there are high incidences of young women there who are in need of a way forward, and this is only one way. But the program started here in Oakland with the same vision. I hope it goes to New York, and then Los Angeles, and also Dakar. I would love for it to go someplace in the Caribbean, too. I was also contacted by a woman in Ethiopia about the program. I’d love to see it there as well.

Besides money, what kind of support can the jewelry community give you? What do you hope for? What can people do?

Karen Smith: We need money, that’s just a fact. But here’s the beautiful thing: the members of the jewelry community who get wind of We Wield the Hammer, or who hear the story, say, “Oh, that’s really cool. I wish there was something that I could do.” So I’ve had hundreds of jewelers buy a T-shirt or a shop apron and rep the program.[1]

Second level of support is, follow us on social media.[2] In October, Lauren Wolf corralled a number of jewelers and they created three sets of stacking rings—gold, diamonds, what have you—that they raffled for WWTH’s benefit. Down the line, we have a couple more of those that are set up or have been promised. Artists who have a huge audience, award-winning jewelers on Instagram with 10,000, 20,000, 50,000 followers, if they raffle something off, they could raise a substantial amount of money for us. That’s awesome!

I would like for people to offer support in the ways that they can but that we identify as a need. What doesn’t work is people saying, “Oh, I want to help. I have this old rolling mill, would you like it?” Why would we want rusted or broken tools? You have no idea how much I had to negotiate that in the last few months—people sending broken, rusty things. They think about us as a charity; they think about us in a different vein than they think about themselves. I always want to ask, “Did you learn how to work metal using a rusty file? Did you learn with broken equipment? Did you learn with cracked stones?” It would be great if the support was actual support, what we have identified as a need, was something that you yourself would accept, and that would genuinely benefit you.

Every nonprofit needs money to get off the ground. I’ve been working on this project two years and I have never paid myself. That’s not sustainable. As the program grows and it really solidifies, I have to have a salary. I have to hire a development person. I have a board, and one board member is working on helping understand the legalities of building a program in another country. One of my board members is working on our 501c3, which, I’m really proud to say, we have in the works. I hope that we will officially have that by the end of the year. Currently we’re fiscally sponsored.

One of the other things that metal artists have done is offer to take on graduates from our program as apprentices. As I mentioned, jewelers have run raffles, including Lauren Wolf, from the shop Esqueleto, who was so taken by the program that she wanted to raise money for us. She’s also making space in her shop to exhibit work by our students. I understand that not everybody can write a check. But there are ways that people can offer support that is genuine and authentic and makes sense. But the truth is, more than anything, we need money.

Is this a hard time to be getting funding?

Karen Smith: Well, here’s what’s funny—it’s a hard time for some people and for other people it’s not. I live in the Bay Area and there’s a lot of money here that gets invested every day. There’s a ton of money here, but few are funding arts programs in this way. Few are funding black women’s opportunities in this moment. Few are funding small programs. It’s not because we don’t deserve it, it’s because we’re nonprofit. You’re not going to make $10 million on your investment from us. But there’s plenty of money in the world, and plenty of money in the Bay Area.

Jack Dorsey, who created Twitter and Square, left Silicon Valley and took with him quite a bit of money, deciding he’s going to simply give away a certain amount of it. He’s just giving it away. A number of people have said to me, “Oh, you should get in front of Jack Dorsey and his Start Small Project!” When I respond that I don’t know Jack Dorsey, the reply is always “You should just tweet at him.” Twitter doesn’t work like that. I can’t tweet Jack Dorsey and then he’ll tweet me back. But people literally say, “Jack Dorsey should know about your program because of what you’re trying to do, because of what it means to your community, he would totally give you the money that you need. So get in front of Jack Dorsey.”

But there’s no application process that I know of. It appears that the way Jack Dorsey supports your program is if he stumbles across you or somebody brings you to his attention. So there is funding, even from Jack Dorsey, happening; the big question is, as always, access.

Readers—do you know Jack Dorsey or somebody associated with him? Can you connect Karen Smith with him? If so, get in touch with her![3]

Karen Smith: I appreciate support that’s thoughtful and that’s honest and that comes from a place of integrity. I appreciate that very much. What has been really challenging in this historical moment are the people who have decided, “Racism is a problem in America, let me do something nice for a Black person.” And that support becomes about making them “feel better.” I’ve had people offer me “support” in exchange for something. One woman offered to send stones to our students for teaching stone setting in exchange for sending pictures of our girls to put on their website to show what they’ve done.

If you’re offering something in exchange for something other than sincere thanks, you’re not supporting us. You’re looking to make yourself feel better. If it’s not about righting a wrong or addressing inequity or helping to support access and access point, then that’s not really support.

Many have ways of thinking about who deserves to do something or who deserves a windfall and who doesn’t. There are a lot of people who have a lot of money and who give money all the time, but they give to particular kinds of organizations. They give to particular kinds of people and they give to support particular ways of life. It’s their right, of course, and we should look at how that works—who gets a leg up, and who doesn’t.

There’s been a lot of discussion in the jewelry industry over the past few months about inequity and access. I’ve stayed out of a lot of the conversation because the conversation isn’t often enough about addressing inequity. The conversation is, essentially, “Let’s provide a scholarship so one Black person can go to a long-established school created by the same people who have kept the institutions homogenous.” How does that address inequity? How does that make systemic change? Why are we having a conversation about providing one or two scholarships to attend a traditional institution? And then what happens? Where does that one newly trained jeweler go? Or do? Why aren’t we addressing how awards get given out? Or who sits on panels and juries?

For the last couple of months, I’ve been highlighting Black jewelers on Instagram because we hear, “There aren’t any.” That’s just not true. There are amazing jewelers who are of African descent. I’ve had my mind blown. In London, for instance, there are so many extraordinary jewelers and they’re coming together because in this moment we’re actually talking about inequity and inspiring and motivating each other through the challenges. In these moments when we’re talking about racism and oppression and lack, let’s really talk about it. If we’re saying, “Oh, we’re so sorry that Black people have suffered” or “We’re so sorry that there’s such a thing as inequity,” if we’re not following that up with real talk about systemic change, we’re wasting our time.

I signed the BIPOC Open Letter talking about access in the jewelry industry because it was really important to start to have those conversations and start to make a way. And that’s why We Wield the Hammer.

As mentioned earlier, WWTH came out of your apprenticeship with the Senegalese goldsmith Ibrahim Sow. Let’s circle back to that. When I was 12, my father’s job took our family to Dakar for a couple years. Dad frequently brought us to Soumbédioune (Village Artisanal de Soumbédioune), an outdoor market where local craftspeople sell their wares. He spent hours talking and bargaining with the artisans. They had wood and metal masks, gorgeous woven baskets, and textiles on offer, among other things.

Karen Smith: That’s where Sow is located, so how fortuitous that you’re interviewing me. A lot of my work since then features masks. Sow’s little shop was directly across from a mask maker. I used to just look at those, and I totally got inspired. That’s how masks have become such a part of my work. And now with COVID, it’s a really integral part of my work. Masks are at the forefront of our consciousness now. Everywhere we go, we wear a mask. There’s also a way that people of African descent have been wearing a mask, all along. And we still do in order to stay safe.

Do you mean specifically in the United States? Or outside of Africa?

Karen Smith: Both inside and outside of Africa; but I’m speaking specifically to this historical moment in the US, and the moments of my lifetime. When I was a child, one of my favorite poems was “We Wear the Mask,” by Paul Laurence Dunbar. It resonated with me even as a third grader, because there’s this way that you have to present in society, right? I think I live it in all aspects of my life. Some of it now is habit and not necessarily tied up with assimilation, but it’s certainly tied up with acceptance and, at this hysterical/historical moment, not being murdered.

You came to metalwork because you had a business based in mindfulness service and products. You were making malas and rosaries and prayer beads, and as people started asking you to make other kinds of jewelry, you had all sorts of ideas for things you couldn’t make with beads. You started with wirework, then learned soldering. You’re self-taught. How did you do that?

Karen Smith: I watched videos… I’m a former academic so the first thing I wanted to do was go to school. But art schools cost a ton of money. So I bought a little butane torch, I read some books, I looked at some videos, and started teaching myself how to solder.

I took one class to teach me how to set a bezel, because I could not figure that out. It was a four-part class, and I missed the first class because of an emergency. The following week, the teacher said he would bring me up to speed, and he took 10 to 15 minutes to go over everything he had taught in the first class. He’s like, “You got it? Good, let’s go.” I didn’t have it. I got the bezels made, but I didn’t understand how it worked. I could mimic what he was showing, but I didn’t understand how it worked. Why was it important to make sure that the back plate was completely flat and the bezel was completely flat? Why was it crucial to make sure the metal was clean? I didn’t get any of that because I missed it.

This ties into the fundamentals-focused approach of WWTH. Your apprenticeship came about after an inner voice told you in several different ways, “You’re going to learn how to make with gold in Senegal.” You discussed that desire with a friend, who put together a group on Facebook Messenger. One of those people was a Senegalese professor who wondered if you knew that in women don’t wield the hammer in Senegal. The form gets transmitted from father to son there. It’s patriarchal. Women can clean metal and sell finished products, but that’s it. You hadn’t been aware of that, but you still wanted to go learn there, and these people helped you find a way. Within 24 hours you had a teacher, a place to stay, and had made contact with expats who spoke English, and you got to Dakar a few months later. Besides Sow, you worked with his son, Oumar, who is also his apprentice, and his assistant Abdoulaye.

Karen Smith: Sow’s father was the goldsmith who worked with Leopold Senghor, the first president of Senegal, and created the medal for his inauguration. So Sow is a big deal, he comes from a line of great goldsmiths. He told me how children start the process. The first day I noticed a bracelet that Oumar worked on. And so he says, “Okay, we can start with forging. That’s not how it usually works, but we can start with forging.” He started showing me how to forge one of those beautiful, traditional bangles. It’s hard work! Oumar is so gifted and so patient and so skilled. He’s been doing it since he was 12, and he’s 24 now. He’s been doing it half his life and he was trained by Sow.

What did you learn from Sow, and what did he learn from you?

Karen Smith: When I started, I made my first mask, inspired by the shop across from us. Sow asked, “What is this?” When I replied, “Oh, I’m so inspired by these masks, I want to re-create one in metal,” he asked, “Why?” I talked about being inspired, about art and spirit and aesthetic. His response? “Hmm…” He starts talking about production and the importance of just making. And my response was, “Well, okay.” We were missing each other.

Later as he was working on a custom piece for a client, he looked at me and asked, “What do you think of this?” I responded that I didn’t like it, didn’t like the design, didn’t like it at all. When I asked him what he thought of it, it turned out he didn’t like it either. I wondered why he was making it.

Sow offered that he made what the client wants. My resistance, my declaration that I only made what I wanted to make because this is my art was met with an incredulous look and a single word: “Art?” We ended up having a conversation about “art” and about work, about privilege and culture. I came to understand that he makes extraordinary things, but he doesn’t think about it as his art. He looks at it as his job, and he makes what his clients want because he has to eat. I understood more about the business of jewelry-making from him; until Sow, I’d been thinking about it solely as an expression of my own creativity. I started to think about the business of making with Sow and I believe he started to think more about inspiration and creativity, because he makes designs that have been made for a hundred years.

He’s not only making things that are traditional but his approach to making is traditional.

Karen Smith: Absolutely. Everything about his approach to making is traditional. He taught me filigree, he taught me to make basic chains. Chain-making in Senegal is so tedious. You start with a pile of silver, you make a rod, you forge that rod, and then you put it through the rolling mill, file that wire, and then pull it through the draw plate until you’ve got something like 30-gauge wire! It took me three hours just to get the wire! And I was sweating! I didn’t want to learn all techniques, I wanted to learn the basics, fundamentals of fabrication. And I wanted to understand how things happen. If I never have to pull 30-gauge wire through a draw plate again, I’ll be happy. It’s physical work, but now I know how to do it, and that was really important to me. I understand better how to use a crucible since being there. The way they do it is incredible. It’s like an old-fashioned metal tub, and they put charcoal in it, and you have to wind it. It brings oxygen in, so you have to wind it and wind it until it gets hot enough. It takes forever! Everything is very physical.

And here it isn’t. I sit at my desk, I reach for my folder, I reach for this gauge of wire, I reach for that gauge of sheet. And there everything is—all the filing happens with sandpaper or with files. Sow has a polishing wheel, but that’s the last thing you do, if you want to do a mirror polish. Everything gets done by hand. It was a most incredible experience.

[3] Email the organization at info@wewieldthehammer.org.