It is difficult to overstate the influence of Dorothea Prühl on the field of contemporary jewelry or simply to trace its bounds. She taught many, inspired more, and enthuses seemingly everyone. It helps that her colliers straddle the fence between the figurative and the abstract. She is that bit of unmarked territory on your jewelry map where these conflicting territories overlap to everyone’s surprise and excitement. It helps even more that various attempts by others to claim that territory have, thus far, not been nearly as convincing as hers.

Despite Prühl’s undisputed aura as a maker and a teacher at Burg Giebichenstein and the fascination that her solitary pursuit of perfection elicits, there is comparatively little material on her written in English. As part of its Best of Interview publication project, AJF decided to redress that and embarked on the complex task of interviewing the rather reclusive artist. Renate Luckner-Bien made the contact possible, and Iris Eichenberg and Benedikt Fischer wrote the questions together. Mr. Fischer met Dorothea Prühl twice, to harvest and later to edit her answers, which were then translated into English by Anna Helm, an alumnus from Halle with previous experience with Prühl’s prose. The text was illustrated by Emmanuelle Duparchy, who came to our attention through the detailed scientific representations of wooden vessels she created for the Musée du quai Branly and seemed a perfect fit with Prühl’s material sensibility (these illustrations are in the book: we used the original picture for this online version).

In short, the 4000-word interview you are about to read is the result of a very collective effort: we were very happy that its release, in printed form, coincided with Dorothea’s Klassiker der Moderne exhibition at the 2014 Munich Handwerksmesse.

To thank the jewelry community for its overwhelming support of our next publication project, Shows and Tales, we have decided to make this interview available online to all our readership. You rock.

—Benjamin Lignel

Benedikt Fischer: It is an honor to be able to do this interview, but I should tell you, I haven’t done this before.

Dorothea Prühl: I am glad to hear that you aren’t a professional. I don’t like to talk so much, but we can give it a try.

Nor do I, but isn’t that why we make our works? They should communicate something, if all goes well.

Nor do I, but isn’t that why we make our works? They should communicate something, if all goes well.

Dorothea Prühl: That’s right. To be honest, I have developed a dislike for all this interpretation, with a lot of psychology and making public intimate things that really are one’s own business. We work with form, and if I need words for it, then the form isn’t good enough. It is such a wonderful phenomenon that a form can express more than an entire story, however small it may be. I am not a poet. I make forms. And I don’t want to tell an entire story. I rely on the form to express my attitude toward life.

Is that also how you taught, I mean, was that connected with your teaching method?

Dorothea Prühl: Yes, that’s how I taught. I have never given any kind of lecture. Theorists can do that better. And you can never say everything, not even in a small community of like-minded people. We need a human counterpart. I need his or her charisma, he or she needs mine, and then it becomes possible to have a very personal conversation that might really be important—for the young people to whom I want to tell something, but perhaps also for me, because I see what they have to say about it, coming from another generation. So, it’s a two-way thing. And that was my teaching method.

And my teaching method was also that my students were permitted to see what I was doing. I worked there—you might say I lived there—so I was always there for the students. They were able to ask me, and even to question me, about what I was doing at the time. In that situation, they saw both how I agonized over my work and they got to see my unsuccessful attempts. They found that encouraging. They saw that it doesn’t all come off at once. They saw how you have to labor, that you can also despair and might have to start anew. There is not much sense in telling them. They have to see it or witness it. And I think that was the best I could give them.

Another thing I noticed is that you took your students to your house in Augustenberg in Mecklenburg, for instance.

Dorothea Prühl: Yes, I did, and I didn’t tell them they had to complete a task there. I took them along and said, “Do what you want to do. This is where I work, and you can find out for yourselves why that is so.” There is the wonderful landscape, the seclusion, the peace, and the possibility to contemplate things. In the city, you have a letterbox full of rubbish. In Augustenberg, I have no telephone, no letterbox, no TV, no radio. It is an exceptional situation in which you are alone with yourself. You can’t go to the cinema just like that. You have to get along with yourself. It is a very special situation I wanted the students to experience, or at least, have an idea of it. And to get along with one another, too, not just living alongside, but everyone washing in the same bowl. That is also part of it.

You might call that a very strong reference and relational involvement?

Dorothea Prühl: I have always relied on these personal relationships between the teacher and the student and also among the students. And then, of course, it was also important to have people who could understand me, and whom I could understand. I was dependent on liking them. If I understood them, I could like them. Only then could I tell them something. There are no general standards. They don’t exist. There is only a very personal view, and you have to find it. And also, for the other person, where is the other person heading? I have to sense it before them. Then I can give them advice. Then I can say, “Forget that. You’re not getting anywhere with this! Take a shortcut here!” It is very difficult to know what you want yourself. All this talk about form, only about form, it leads to nothing. Because the form, well, it doesn’t matter. The attitude toward something—that’s it. The form has to come following that. And then it will come by itself.

With some confidence?

Dorothea Prühl: It doesn’t come by itself. It comes from labor. It all has to do with work, with a lot of work. But if you only rely on the form, then you are on the wrong track.

In your opinion, what have you achieved? What is the task of the teacher?

Dorothea Prühl: You offer a protected situation to the young people, in which they can expect advice and help. To gain freedom and personality is crucial. It is the actual issue, and much more important than a result that you can place on the table.

At Burg Giebichenstein, students are faced with such a wealth of offers. What role does the jewelry class or the workshop play in an art study program?

Dorothea Prühl: The students were in the jewelry class, and then during their foundation training, they did plastics and drew and much more. But, they were at home in the jewelry class. It was the point from which they set out to do all these other things, and the other things were exercises for it. Most people who make jewelry don’t actually want to make jewelry. They want to be artists. And that is a big difficulty because “art maker” is even less a profession than “jewelry maker.”

Making art and/or making jewelry: how did you come to a decision for yourself?

Making art and/or making jewelry: how did you come to a decision for yourself?

Dorothea Prühl: It is my lifelong attempt to make jewelry and not lose my artistic aims. How far I can achieve that aim, I don’t want to judge. But I have never abandoned that challenge, and I want my works to be applied works of art. Because that gives things a meaning. Art, or what we call art, has always been applied in some sense. But at some point, it got separated. It is a very unfortunate fact that art and life are separated. Take the sculptures in the Naumburg Cathedral. Well, the benefactors had to be portrayed because they had given the money. So it was applied art. What we call art should not become some kind of abstract thing. It should have to do with life. And when I make jewelry, then it has to do with life. There are always the donors, the collectors, the benefactors, who make sure it doesn’t all trickle away in poverty and indifference.

Another wonderful phrase of yours is that you consciously decided not to live from jewelry making. That fact must surely offer additional freedom.

Dorothea Prühl: It’s true. I consciously made that decision. I have never worked as a self-employed artist. I was very lucky to have this position at Burg Giebichenstein in Halle. But I can say that I would have rather delivered letters than do something in my workshop that I dislike. My work has helped me getting through the difficult patches in my life. There was always an open door through which I could escape.

What were your studies like? How would you describe your relationships with your teachers?

Dorothea Prühl: The only person from whom I reaped some benefit was the painter Lothar Zitzmann. He taught us the foundations, an art-based craft. Not art, he always emphasized that, saying “I can teach you the craft. I tell you which forms are right and which are not.” And that was very helpful. It was tangible. The sculptor Karl Müller was a wonderful teacher and a great artist. But when I was a young trainee, he could not take me seriously. I hadn’t completed a jewelry-making apprenticeship. Müller’s successor only left broken pieces, and when he left, I started working with Renate Heintze, who later headed the jewelry class. We cooperated in a friendly and fair way. I held a university teaching post, so I wasn’t in a position to develop academically. And I had no possibility to develop any ambitions in that respect, because I wasn’t considered a politically and ideologically reliable person. I was just only tolerated. At that time, I had already lost my hopes for a better socialist society. And so we developed, against massive resistance, a concept to think and make jewelry beyond the narrow paths of tradition and functionality. I enjoyed teaching and did it with all my heart, and I think with some success. My artistic staff member Andrea Wippermann and workshop leader Arno Friedrich were also part of that success.

Then, the political changes began in the GDR (German Democratic Republic). One year later, Renate Heintze died. I was in charge of the class, and at the same time, I had to apply for the professorship of the class, which was tendered for the first time. I was appointed professor and suddenly earned a lot of money. That was new in my life. And with the political changes, after 1989 everything else changed, too. I was free to exhibit, to get any information I wanted, all the things that had only been possible to a very limited extent. It was wonderful, and about time, too. The way we had been living was really anachronistic in many ways.

Young people today find it hard to imagine that I was almost 60-years-old when I had my first solo exhibition. It took place at Galerie Marzee in the Netherlands. Galerie Marzee was a stroke of luck for me and for my students, because Marie-José van den Hout does not only exhibit renowned names. She offers young people the chance to develop and to present their works, and she is happy to take the risks that come along with that.

I have tried to discover changes in your work before and after the political changes, but I haven’t found any.

Dorothea Prühl: I don’t think I was greatly altered inside. I couldn’t have, really. If you have already reached a certain maturity and have found out what you want, then such external changes aren’t decisive. For that reason, my work surely hasn’t changed. There was, however, a certain irritation. In the years between 1990 and 1995, I hardly created anything worth mentioning, except for a ring for my sister and a small wooden shape for my daughter. I had experienced such periods of paralysis during my studies, too. For a long while I created nothing because all I knew was what I didn’t want. I didn’t want to make all those small bits, but there was nothing I could have set against it. It was only after my studies, during my time as a designer in a state-owned jewelry firm, that I found my own way towards a free application of forms and materials.

How do you assess the situation of young jewelers today?

Dorothea Prühl: I am quite well informed. I wouldn’t dare to judge what the enormous changes in circumstances that took place within the past 10 years mean for the lives of young people today. Changes or not, the basic questions are always the same. Is it possible to reflect on living and dying and to make a piece of jewelry about it at age 20? Big words! Big issues! Sometimes I think the young ones want to sell the food before it is cooked. Amongst other things, neglecting craft skills and this unwillingness to work intensely means an impoverishment to me. I believe in limitations. Young people don’t take enough time. Perhaps they haven’t the time any more. With all this freedom, life has become more exhausting. Some of the moral concepts back then were certainly too firm, but they did help to find orientation in life.

You work both in Halle and in Mecklenburg. This question is of personal interest to me because I was born and grew up in Austria, on a farm in the countryside, myself. I, too, have a great longing for the countryside.

You work both in Halle and in Mecklenburg. This question is of personal interest to me because I was born and grew up in Austria, on a farm in the countryside, myself. I, too, have a great longing for the countryside.

Dorothea Prühl: So, how do you feel now, in the city?

I have lived in Vienna, Amsterdam, and Stockholm, and Halle is only a small city, something in between. But I feel at home in nature, out in the country.

Dorothea Prühl: I can relate to that very well. At the bottom of my heart, I am a farmer. I am not a city person. I grew up as a refugee’s child in Wroclaw, in a small village community, and I was very happy with village life. When I came to Halle, I was very simple and not very educated. That was my luck, but I also got in conflict with these elitist things that were demanded of me at Burg Giebichenstein. At the beginning, I found Halle and the art school very strange. So, if you ask me what heimat is for me, then I would say my soul is more at home in Mecklenburg. However, without the city, I would be working away in Mecklenburg, and after five years’ time, I would have forgotten my name. In Halle, I have friends and professional contacts. In Mecklenburg, there are foxes, toads, and cranes. I live comfortably as a prince, with a villa in the countryside, and in winter, the parties in the city. What a great life!

When you are there, you are alone?

Dorothea Prühl: It is arranged so that is possible. And I want it that way. After all, that’s what I come for, the peace and seclusion. And the landscape—massive hills, not mountains, they are massive hills. It is an end moraine landscape with a lot of muddy forest mire. At times, it is totally flooded, so it can hardly be cultivated. When I walk in the forest, I meet no one for hours.

So there are toads in Augustenberg?

Dorothea Prühl: Yes. When I go there in May, I hear them calling. A spherical sound, very unworldly. Toads are extremely timid, and you are lucky if you can get one on your hand. It then turns upside down and shows the bright orange specks on its stomach to scare away its enemies. Perhaps it works, but it makes me laugh each time. It makes me happy to hear the toads. And to see the cranes gather and hear them call. Then, in autumn they depart, huge formations of them, and all you hear is the sound of their wings. There I stand and feel left alone and deeply moved, as if I had to gather all my strength to arrive safely, like these birds.

Your apartment, your workshop, your direct surroundings are characterized by an honest sort of aesthetic. How do you live nowadays? What does it mean to live in a certain environment?

Dorothea Prühl: Yes, I don’t know, perhaps you can call it honest. It is all arranged as I need it. Rather reduced, clear, and practical. One doesn’t need much. The apartment is also a workshop, and one likes to be where the action is anyway. Everyone likes to sit in the kitchen. I wouldn’t know what to do in one of those overly upholstered living rooms.

Please tell us a little more about your works. In the English language, there is the term “benchmark,” which means reference value or comparative value. Comparing the standards. I would like to find out if there is a work of yours that has reached a level you would like to reach again at a later point, either in a similar or a different way.

Please tell us a little more about your works. In the English language, there is the term “benchmark,” which means reference value or comparative value. Comparing the standards. I would like to find out if there is a work of yours that has reached a level you would like to reach again at a later point, either in a similar or a different way.

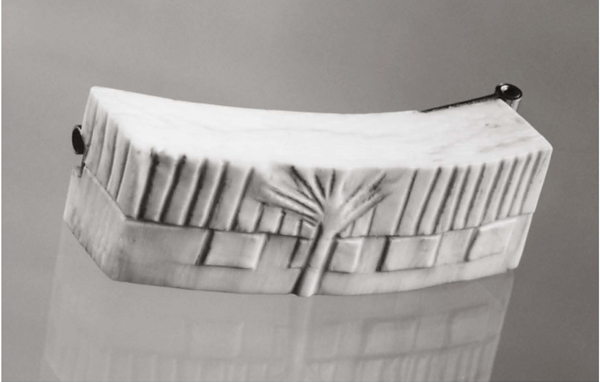

Dorothea Prühl: There are two works that mark such a point. The first is a small ivory brooch, Haus (House) from 1978. It is very unobtrusive, slightly naïve but elegant, and for me, very important because I was feeling so comfortable with this little shape and would still defend it against the whole world, to this day. I only realized much later that this piece helped me find out what I wanted. Perhaps if you love something, then you can find a form for it, too.

And the other one is Windblumen (Wind Flowers) from 1989. These big open shapes made of silver. I haven’t been able to achieve that again later.

Would you agree that the earrings Stern und Kugel (Star and Sphere) have a slightly different feel than the rest of your works?

Dorothea Prühl: I can’t really say, but I would say that Silberne Frösche (Silver Frogs), which I made in 1984, have a different feel. They have remained relatively strange to me, although there is no work that I puzzled over longer and harder. Skin and bones well, like frogs. It is a hollow, mounted, rather refined construction with a wire skeleton inside and thin silver sheet stretched over it. Perhaps I still see too much of the effort that went into these frogs. I didn’t continue with that construction principle. But I have made a fair amount of those frogs. It was fun to give all my friends a frog. I had, however, spent two years figuring out the form!

What is it like to part from your works? Is it like letting children go when they’ve grown up? Do you find it hard?

Dorothea Prühl: It used to be hard. It’s become easier. And it really is exciting to see that someone finds my works desirable.

When looking at your works, I noticed that they seem to become more reduced, more essential. More reduced without losing relevance. Quite the opposite, they seem to gain relevance. It seems as if you were getting closer to the core of things and as if you were less afraid of misunderstandings.

Dorothea Prühl: With time, the rhythm that comes out of the alignment of like forms has become more and more important to me. When I say “closed form,” I mean the necklace, a moveable shape that has to form a plastic entity. I get closer to the ornament. For these shapes that are similar amongst themselves, I need to find a construction principle in which they appear unique and can hold up to being strung in sequence.

So, I have to refine, and that means to unwrap things. And it also means that the things become bare and hard. So it means a loss, too. You win and you lose at the same time. Well, I guess that’s life. When you are young, everything is full, soft, possible, and then as you get older, everything is refined. It’s a process that happens in life, and it’s quite possible that it is inevitably reflected in one’s work.

In your opinion, what are the good sides of aging?

Dorothea Prühl: The big gain is that you really are less afraid of misunderstandings, as you suggested. So, you do what you can do, and the way you see things is the way you see things at that age. And so you have to be content with it. There is no sense in trying to go against that. I am not as elegant as these very old forms any more. I don’t think like that any more. You think in a bigger context, or you look for fundamental structures that lead away from the individual and exclude the accidental to a large extent. Structure is what remains.

Dorothea Prühl: For me, material is not just some stuff that you use to realize an idea. Material is substantial, it is alive, and I respect what it can or wants to do, in my own interest. With more experience, I cannot consider the material separately from the idea. For that reason, I need to do my sketching with the actual material, while I am still searching for the form. This can be very time-consuming, because you can only rarely get the form right at the first attempt. It hardly ever happens. Most of the time, it is a painful and tedious way, though not without stimulus. And where I get to remains unclear for a long time, and it is often surprising for myself.

There is a piece of your jewelry that I find fascinating for its otherness. The golden bracelet from 1987.

Dorothea Prühl: That is not my own work. You can find such bangles in historic collections. This is the story: As a jewelry maker in the GDR, you could only get a certain amount of gold for yourself. The amount allotted to me was not sufficient, so I had to search on the black market. There was a Cambodian who sold gold. He offered me this irregularly shaped gold wire. I soldered it together and put it on my arm because I thought I could do nothing better with it. That gold cost me 7000 German Marks back then. It was a fortune I did not have, and I had to borrow it all. I could have bought a small car for that money.

Was that a political issue for you?

Dorothea Prühl: The fact that we tried to get around such limitations? Oh, we all had such political issues.

I feel that one of the great qualities of your works is that they are accessible to everyone. There is no hierarchy in how far they are understandable for the viewer.

Dorothea Prühl: I am happy if that is so. I don’t want to work for a certain informed clientele. I want my things to have a beauty that is accessible to many. It also has to do with material, craftsmanship, and how a thing feels in the hand when you close your eyes. Sometimes, the idea of it is enough to like it. The thing needs to radiate something that goes far beyond the optical perception.

Sometimes I wish to be free from all the restrictions that come with usage. But at the same time, I know that I set these limits myself. The disadvantage is that I move in circles, within the limitations that come from my determination to make a piece of jewelry. It means moving in circles or in a modified sort of repetition. I would like to invent new things, but in the end, the circle closes again. You are caught in what there is and in what you are. But you need to understand that at first. To understand, but never stop banging at the prison gates.

Another piece surprised me because you used color—Blätter (Leaves) from 1976.

In order to leave only the essential in that respect, too?

Dorothea Prühl: No, it wasn’t such an intellectual, theoretical decision. It happened that way. I left out the colors because I didn’t feel like it. A lot of what I do is based on feeling. But I am not afraid to try and find out how a construction really works. I find it painful to see something that is constructed badly.

At the beginning of our conversation, you said that you only had about two ideas every year. It seems to me that you draw from a never-drying well of ideas. There is always something new.

Dorothea Prühl: It doesn’t seem so new to me. Everything I make must be at least new enough to interest me. Yes, it is true. If I have two good ideas in a year, I am happy.

What is it like to have done all these pieces? How does it feel?

Dorothea Prühl: I think that I have a good life. And I am grateful for it. I don’t think that I could have been happier in any other profession. All these years I was very closely connected to the university, but the university was not my life. My own work was my life. And that’s why it wasn’t so bad to go.

It is good that there is a line of tradition that I can be part of. It represents culture and is important for life as a whole.

Translated from the original German text by Anna Helm.