I had the pleasure of asking Barbara Paris Gifford, a juror on this year’s YAA panel, a few questions about her work as a jewelry curator and arts professional. This year’s jury team also includes artist Bifei Cao (who won AJF’s 2018 Artist Award) and collector Jorunn Veiteberg. Gifford is a contributing writer to AJF and an assistant curator at the Museum of Arts and Design (MAD) in New York City.

Chava Krivchenia: When you act as juror, what are some key traits you look for in candidates and their work?

Barbara Paris Gifford: First, I actively notice my visceral reaction to the piece. If I feel neutral about it, or as if I’ve seen a similar idea before, that’s usually not a good sign. I want to feel something, whether positive or negative—and I do not want to feel indifferent. Second, I want to understand what the work is about. Is it doing that well? Does it feel authentic? Is it relevant? Third, I consider how the piece is made. Does the making feel appropriate to the piece? To the concept? Does it make sense? Is the piece resolved? I trust my eyes and the feeling I get from the piece the most.

RELATED: Interview with Lynn Batchelder, 2016 AJF Artist Award Winner

RELATED: Barbara Paris Gifford Interviews Anni Nørskov Mørch, Curator of The Splendour of Power

RELATED: Interview with Kellie Riggs, Curator of Non-Stick Nostalgia

How do you think the award changes jeweler’s careers?

Barbara Paris Gifford: There’s a lot of great work happening out there and I think it’s wonderful that AJF can recognize it with this award. It can bring a lot of attention to a young artist’s practice, and certainly the money is helpful, but it’s ultimately up to the artist to use it in a way that makes an impact on the trajectory of their careers.

Not only are you assistant curator at the Museum of Arts and Design, but you also actively contribute to publications and other projects. How do you decide which projects and exhibitions to become part of or lead?

Barbara Paris Gifford: Deciding what to write about and what exhibitions to mount are really two different things. They can be related, but often they’re not. Before I write an article, for example, I have to feel that I can contribute in a meaningful way to the material that already exists on the subject. If I don’t feel I’m well equipped or that I don’t have the time to do the necessary research, I won’t accept the assignment. Everything I’ve written thus far was because I was very passionate about the subject and felt it was worth taking a risk by adding my voice to the mix. As for exhibitions, there are a lot of factors that go into mounting one: Is the work worth visitors seeing? Does the work substantiate the thesis? Can there be a marriage between the written and visual narratives that is worth seeing? Will visitors be interested in the story being told? Can we fundraise for it? Does it make sense at the Museum of Arts and Design? There are many risks involved, which is why the work of curating is so attractive to me.

MAD is a collecting institution. How do you think you’ve shaped the permanent collection, and what do you hope to add to the museum’s collection in the future?

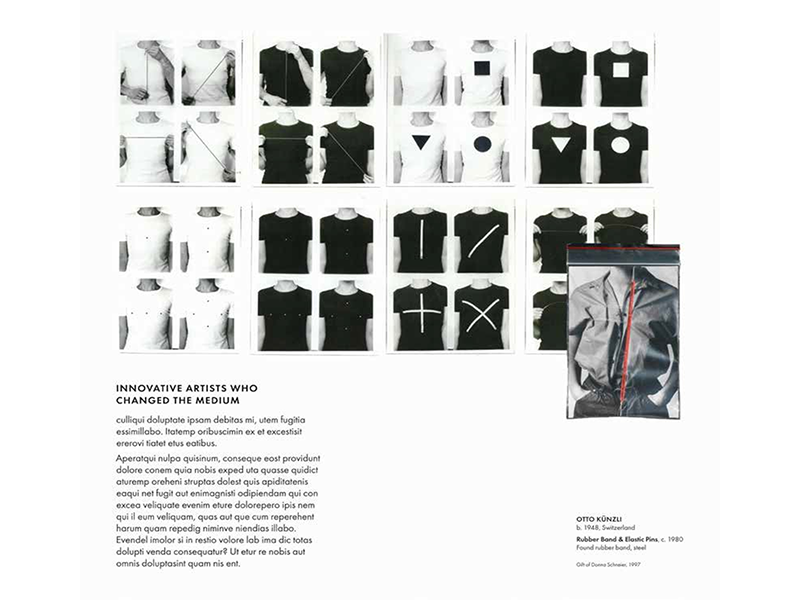

Barbara Paris Gifford: MAD’s studio and contemporary jewelry collection is stellar, as the institution has been collecting jewelry since the 1950s, when the field began. I’m part of a long line of curators, including Paul Smith and Ursula Ilse-Neuman, whose job it has been to ensure the collection maintains its relevance. Over the years, this hasn’t been easy as financial resources ebb and flow. Still, the museum has nearly 1,000 pieces of contemporary jewelry by many of the most important artists in the field. Our collection represents one-third of our holdings and is the closest we come to having a category that is encyclopedic. My goal is to continue to acquire representative pieces from artists who should be in our collection, both those we missed in the past and artists working in the field today. Since Alexander Calder and Harry Bertoia are credited as being the fathers of studio jewelry in the US, my dream is to acquire at least one piece from each.

Tell us a little bit about the work leading up to 45 Stories in Jewelry, your upcoming exhibition at MAD. What do you hope the public gains from it?

Barbara Paris Gifford: MAD is one of the few institutions to have visible collection drawers in which to display jewelry. This presents an opportunity to educate visitors about the history of our field. While there are many histories that can be told with studio and contemporary jewelry, as the medium is worldwide and came about in a myriad of ways, our collection allows us to tell the history largely from a western perspective. Since we have 45 collection drawers (hence the title 45 Stories in Jewelry), we will be telling 45 different stories about jewelry artists and their contributions to the field. I worked with an amazingly hard-working and knowledgeable committee (Toni Greenbaum, Timothy Veske-McMahon, Bella Neyman, Erin Daily, Brian Weissman, and Sasha Nixon) to determine the object checklist and the authors who would write each story. We thought it fitting to not only celebrate the artists, but also the authors and supporters of the field who have promoted this small medium and propagated it around the world, into the collections of many important museums. So, for example, Ellen Mauer-Zilioli wrote about Bruno Martinazzi, and Joyce Scott penned the piece about Art Smith, her mentor. Each drawer panel will have its own context, presenting relevant photos, ephemera, or backgrounds that best fit with the artists and their pieces. No two drawers will present jewelry in the same way, as the visual narrative will reinforce the written one. Thus, when visitors open a drawer, they’ll be greeted by the jewelry and something visual that relates to the artist and/or the work. The show will open in February 2020, with a catalog to follow in November 2020, during New York City Jewelry Week. We’re also planning many public programs to extend the learning from the project.

What’s the greatest challenge you find during the curation process?

Barbara Paris Gifford: Like all creative endeavors, the challenges of any process are always worth the privilege of being able to do them. It still blows my mind that passionate people commit thousands of dollars to public spaces so that artists and curators can tell their stories. It’s earnest and beautiful and represents the best in humankind. It’s also a lifeline to all artists to be able to live creative lives. After having a career in advertising, where every dollar needed to make sense on a balance sheet, I’m still in awe of the thousands of dollars it takes to make an exhibition, the short amount of time it runs, and the fact that that is okay. That said, the budget is always an issue and revising the checklist and design is a constant until the time is up and the show must go on. It can be a real nail-biter!

You also have a degree in business. How do you think that influences the way you pursue exhibition curation and your work?

Barbara Paris Gifford: My degree is in marketing research and I worked in advertising for 20 years as a consumer anthropologist (we were called Planners). Basically, I traveled the world interviewing people about many different subjects and then communicated what I knew to copywriters and art directors. My job essentially was to do an immense amount of research, synthesize it, and tell what I’d learned to creatives who may not know a lot about their subjects. Oddly, those skills transferred well to exhibition making. I’m still doing research and telling people about stories with which they may not have much familiarity.

Have any recent shows opened up the way you think about metalwork or the design field more generally?

Barbara Paris Gifford: Kellie Riggs’s exhibition, Non-Stick Nostalgia: Y2K Retrofuturism in Contemporary Jewelry, at MAD, was groundbreaking about millennials and how they and the Internet are shifting the field. I think we thought technology would change jewelry to be more functional—maybe our brooches would turn into flying scooters à la the Jetsons?—but in fact, the lines between real life and our Internet lives are blurring and jewelry is serving to further define our personas online. Millennial jewelers reject the white cube, the elevation of contemporary jewelry as art, and the display of contemporary jewelry on black clothing in favor of context, jewelry as jewelry, and jewelry that supports you, not the other way around. I think there’s a lot there that we’ll be discussing for a long while.