Bonnie Levine: Congratulations on being a finalist in the 2021 Susan Beech Mid-Career Grant competition—that’s quite an honor! I’m sure our readers would like to know more about you. Tell us how you got interested in the jewelry field and your professional journey to where you are today. How did you go from a sales representative to a PhD researcher, maker, and author?

Ana Passos: Bonnie, thank you so much! It was indeed a great honor and I’m so proud especially because it has made me reflect on what you’re asking me: my professional journey so far. It has been a long road—35 years and still learning and maturing ideas.

Sales representative sounds a bit more lofty than what I was actually doing. In the mid-1980s, I was visiting jewelry studios and workshops in Brazil, choosing pieces—mainly in silver, which was hugely popular then—and working hard to find the perfect match within my clientele. After a while, it became a real business. My mother and I traveled across the country and many jewelry artists and craftsmen made a living out of our ability to sell their jewelry.

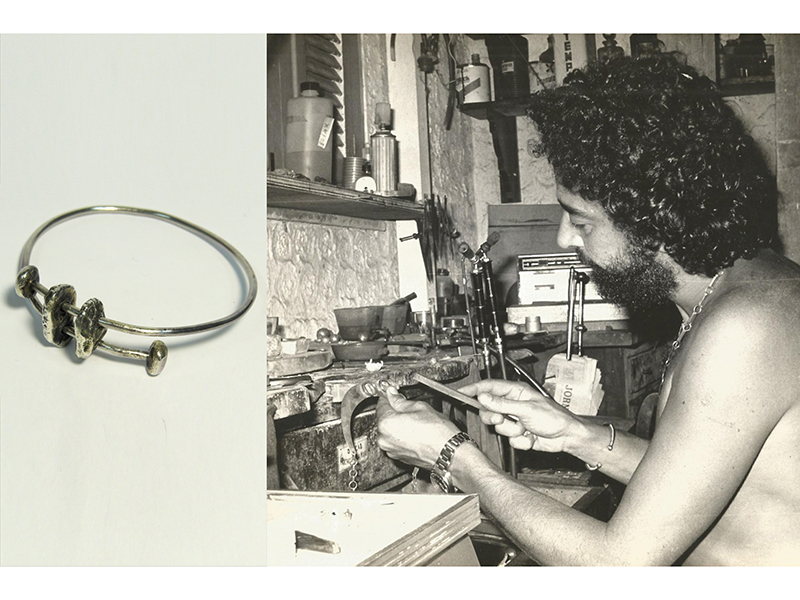

In that line of work, at some point we must deal with repairs and special requests, which led me to deal with goldsmiths on a daily basis. I will never forget the first time I saw a goldsmith’s bench. I was raised to pursue an academic career. It was a turning point in my life. I just had to work with my hands. I had to create my own jewelry. I had the great opportunity to study with two Brazilian art jewelry pioneers: Marcio Mattar and Caio Mourão.

Years later, the business lost momentum and I returned to my academic studies and built a corporate career. Though I never left jewelry completely, I have worked in different industries, and when I look back I realize I was just bringing together the knowledge and resources to become fully committed to the jewelry universe. In 2008, when I left the corporate world, I promised myself to dedicate my time exclusively to putting my skills to the service of jewelry. I’ve been researching, writing, teaching, being an entrepreneur, and working with the creation, restoration, and renovation of jewelry ever since.

My motto is “tenderness in jewelry.” I don’t know if it makes sense in English, but sharing all I know with anyone who wants to enter this world is a goal. If I can do this while nurturing someone’s dreams, it’s even better. I honestly believe that we must celebrate those who came before and provided us with all the opportunities and knowledge they had by passing down what we’ve learned to others.

The jury was impressed with your proposal for the Susan Beech Mid-Career Grant. Tell us about it and your inspiration.

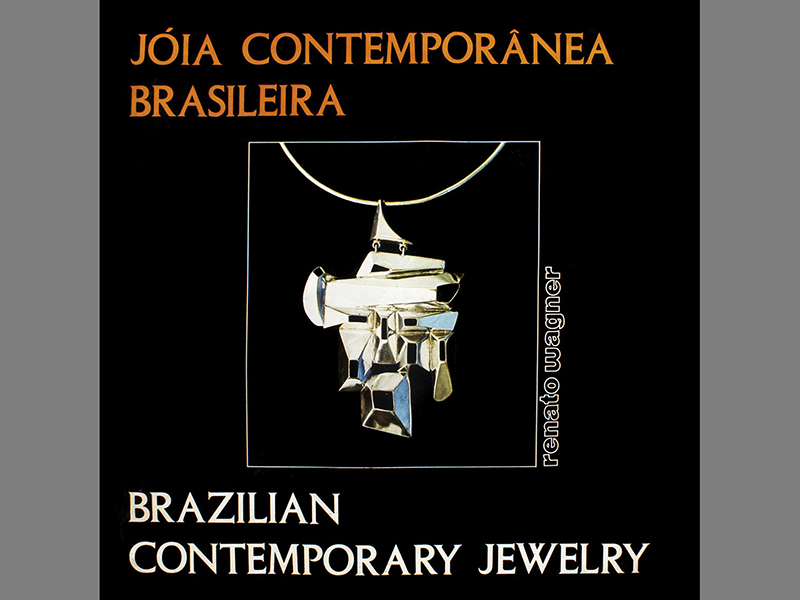

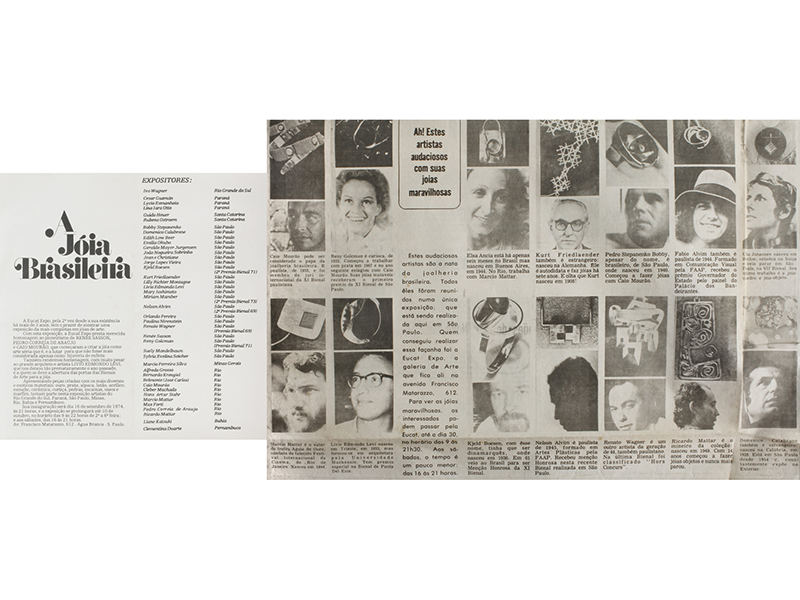

Ana Passos: There was an impressive artistic and artisanal jewelry scene when I got involved with jewelry, and we could trace it back to the early 1960s. Unfortunately, there is little memory of the period except for some artists’ archives, a book published in 1980—Renato Wagner’s Brazilian Contemporary Jewelry—and the catalogs of the five editions of the São Paulo International Art Biennial in which there were jewelry exhibition and awards.

In 2005, I was invited by Michael Striemer, with whom I studied for 10 years, to participate in an event that celebrated the careers of the pioneers of Brazilian art jewelry and introduced new talents. It was another great honor I will cherish forever. Many of those people I had met before, but up to that moment I’d never perceived them as trailblazers. They were amazing. Their body of work was incredible. Nobody knew them, so I decided that I would tell their story one day.

Years passed which I dedicated to establishing myself as an independent maker and researcher. In 2014, I decided to go back to university to be up to the task. My project was ambitious and quite similar to Cristina Filipe’s research, for which she won the 2017 edition of the Susan Beech Mid-Career Grant. Brazil is a continental country. People and information were dispersed, unfortunately. Many artists were already gone. I cannot count how many doors closed in my face. Here and there, people were trying to put together pieces of that history with great effort. My doctoral advisor, who was working with material culture at that point, suggested that I should work with what I had in my hands: 12 years of narratives about the jewelry that had passed through my studio. I wrote a PhD thesis about the construction of the meaning of jewelry in Brazilian contemporaneity.

I continued to believe in the importance of my original project in the back of my head. Besides a possible contribution to the history of jewelry with the identification of affiliations and influences, there were two questions that I would like to see answered. Firstly, why did art jewelry lose its space in the 1990s? Then I tried to narrow down the research to make it more feasible, and focused on a gender issue. How did the female pioneers deal with all the prejudice and misogyny then, since it is still present, even when women have become the majority of makers, especially in the contemporary art jewelry scene? That is how I got to the present project: Brazilian art jewelry female pioneers.

You describe the golden age of Brazilian jewelry as being from 1965–1985. Why was jewelry thriving during that time, and more importantly, what happened after that to make the jewelry world in Brazil go silent?

Ana Passos: If we draw a parallel with other cultural manifestations—music, theater, cinema, dance, and fine arts—the flourishing is easily explainable. The effervescence of the 1960s and the political circumstances were the perfect storm for anything related to self-expression, youthful rebellion, and identity for both the maker and the wearer.

Though many of the great names of that period were still working and present in the landscape during the 1990s and the 2000s, there was a noticeable change in the reception of art jewelry.

There’s a lot of speculation around it. Some people blame the 1990s aesthetics and the yuppie culture. Others believe that the growth of the jewelry and costume jewelry industries brought to the market many other possibilities of adornment and most of them related to the attraction, ease, and velocity of the fashion system. There are those who suspect that, after more than 20 year of dictatorship, the process of redemocratization may have made us more complacent, less inclined to bring something new to the table. (I would love to investigate the latter.) We shall also consider the possibility that the lack of formal education around art jewelry prevented us from continuing the development of the field in a more structured way and setting up a Brazilian perspective and identity.

I’m still trying to create some sense of all those sparse ideas. I hope the pioneers, or their families, can help me move forward in solving the mystery.

Who were some of the female pioneers of the movement? Are they still alive and working today?

Ana Passos: I’m totally fascinated by the pioneers Renée Sasson, Ulla Johnsen, Reny Golcman, Clementina Duarte, and Miriam Mamber. I can also list Miriam Korolkovas and Paula Mourão from a second generation that came immediately after the first one. Most of them are still active. Golcman had a biography written by me, with photos by José Terra, when she celebrated 50 years of jewelry, in 2015. Her most recent work is profoundly related to her early years. Korolkovas is an important curator and activist. She is an ambassador for AJF. Paula Mourão is a prominent teacher and jewelry artist based in Rio de Janeiro.

Tell us about the contemporary art jewelry world in Brazil today. Is there an aesthetic that is unique to Brazilian jewelry? Are educational opportunities available for young makers today? Are there galleries to support the artists? Do Brazilian museums value and exhibit contemporary jewelry?

Ana Passos: No, definitely not. Brazil is a vast and remarkably diverse country for us to look for a unique aesthetic distinction. Traditional jewelry is more connected with some colorful disposition and some reminiscence of our extravagant baroque. I feel contemporary jewelry tries to get as far from those idiosyncrasies as possible. I have mixed feelings about this strategy when I consider our cultural inheritance and all the possibilities it offers.

Also, as we don’t have formal education in the field, people usually turn to European and North American institutions, literature, and professionals in the search for references.

Most of the education opportunities are in the field of fashion and product design, with very few in arts. There is almost nothing in humanities or social sciences that could help us address issues of meaning, memory, and history. I can highlight the work of Professor Ana Videla, at Cariri Federal University, in northeastern Brazil. Her students are working with local materials and particular issues. I’ve recently watched a presentation and was in awe of the quality of the results achieved.

Fortunately, in the last decade, important study groups and collectives have been created. Grupo Broca (2013), Grupo Occo (2015), and Grupo Orbe (2016) brought the perspective of reflection, exchanges, and production carried out collectively. It is worth mentioning that this movement also made possible international exchanges, as we could observe when Brazilian jewelry artists from Grupo Broca—Miriam Pappalardo and Renata Porto—acted as curators of a great exhibition of Brazilian artists within the scope of the 2018 edition of the Bienal Latinoamericana de Joyería Contemporánea of Buenos Aires and of the commemorative exhibition of Joya Brava Chile’s 10th anniversary, in 2020.

In addition, we have several events that enhance the production and the thinking, such as: the 14 editions of the Atelier Mourão Open Doors, in Rio de Janeiro; the two editions of Brazil Jewelry Week, in São Paulo; and the four editions of Reflections, by Miriam Korolkovas, in São Paulo and abroad. Those events are responsible for the contact of the jewelers’ recent production with the public, establishing fruitful dialogues and awareness. It’s important to recognize their role in building an audience for the sustainability of contemporary jewelry, which requires the figure of the other to become visible and understandable.

The holding of contests such as Fio, in its two editions promoted by Galeria Alice Floriano, and Estúdio Escambo, by Nina Lima, can also stimulate the production of jewelry and educate the participants on a more professional presentation of their work. The challenge of participating in a contest, whether national or international, usually results in new investigations and a deeper understanding of one’s own artistic identity, as well as the production of more jewelry and texts.

We have a few institutions with historic jewelry in their collections, but almost nothing of contemporary jewelry. There is a group of art jewelry pieces in a museum in São Paulo that is more related to the origin of the artist than to the fact that they are pieces of jewelry.

In recent years, Brazil has experienced challenging times politically, socially, and economically. What effect has this had on the cultural and artistic world there, particularly contemporary jewelry?

Ana Passos: It’s almost impossible to create without considering our current circumstances, both locally and globally. Jewelry artists are more and more interested in local arrangements that allow a more complex discussion of our reality. They are exploring possibilities within the country and the region, partnerships across Latin America. There is an understanding that identity, ancestrality, and diversity are important issues to address in the coming years.

People are becoming more interested in the history of jewelry, but beyond a Eurocentric perspective. A new interest in adornment of other groups is visible: original peoples, those brought to the continent as an enslaved population, immigrants from all around the world who arrived here in the 20th century.

Other subjects have become even more relevant during the pandemic. Citizen participation, sustainability, and climate change are frequent subjects and art jewelry reflects it. There are still plenty of misleading ideas and a lot of greenwashing, but we are progressing quickly.

Reality is once again an important theme for jewelry. Concepts widely discussed in public and private life are beginning to be incorporated again. The crisis is above all aesthetic. Sometimes I find myself wondering if this is not what we needed to reinvent ourselves as humanity and as jewelry artists.

What is your professional focus right now?

Ana Passos: Focus? I don’t believe I can use the word. I can tell you about my three main activities right now and for the time being. I’m redesigning the project I presented for the grant. I’m in negotiation with a person interested in sponsoring an important part of it. Like me, that person believes that those jewelry artists deserve to have their stories told and their art known by a broader audience.

I have ongoing educational projects in partnership with Atelier Mourão[1] and Galeria Alice Floriano.[2] We are exploring new approaches to old problems. That is a direct result of the pandemic: online contact with people from all over the country, all over the planet.

Finally, my work as a maker has been dramatically affected by all this research and writing. After years of a very commercial approach to jewelry making—which I confess financed all the other activities—I’m inclined to go back to a more authorial endeavor.

What are your thoughts about the importance of opportunities like the Susan Beech Mid-Career Grant for the field? What about for you as a finalist?

Ana Passos: The Susan Beech Mid-Career Grant is so important for the jewelry community. We do need more and more in-depth works—both artistic and academic—that can contribute to the development of our field. Just applying is a great opportunity because it obliges us to put into writing a project.

Though I was not the recipient of the grant, there was a tangible win in taking second place. (By the way, Iris Eichenberg is a powerhouse who truly deserved the prize!) It elevated my spirit. A lot. The project that I’ve been nurturing for so many years—and here is the importance of the mid-career concept—was considered meaningful and relevant. I will pursue its completion and for that I have these new credentials. I believe that all the other finalists were just as energized as I was and I hope they will be able to find other sources for financing their projects.

I’ll be always grateful for the validation, the recognition, and the visibility of my project. It took me a while after the announcement to realize the importance of the achievement. It came from my Brazilian colleagues who one after the other stressed its importance precisely because we are on the periphery of the jewelry scene. They made me realize that it was our prize.

And so I take the opportunity to say that Art Jewelry Forum is one of the most precious resources of information, especially for those of us spread around the world.

What have you read or seen lately that has made an impact on you that you’d like to share with readers?

Ana Passos: Right now, I’m reading Li Edelkoort’s Labour of Love, published at the end of 2020. It’s a beautiful publication. As one of the most important trend forecasters we have today, she presents a renaissance of a craftsmanship—broadly, rather than in any specific fields—that combines a comeback of interest in natural materials and ancient techniques with the most recent technological research on those topics. It is thought-provoking and opens many possibilities for jewelry development.

I’m also interested in publications related to decolonial and feminist approaches, a possible shift to what have been called the epistemologies of the South, and the concept of the Anthropocene. The works of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Ailton Krenak, Boaventura de Sousa Santos, and Bruno Latour are present in my lectures and classes, and their ideas have even been influencing my work on the bench as well. I see new developments in my work on the horizon.

I would suggest two Brazilian movies that I recently watched again for those who are interested in our culture and something that has been called lately the deep Brazil: Central Station (Walter Salles, 1998) and Bacurau (Kleber Mendonça Filho & Juliano Dornelles, 2019). Both are internationally acclaimed movies and a little bit disturbing.

On a lighter note, who can resist the British reality show All That Glitters? It’s amazing to see a jewelry studio on TV!

Thank you very much, Ana. Many congratulations on being a finalist and all best wishes to you!