German artist Felix Lindner creates colorful jewelry that combines common materials, such as pieces of plastic toys, with exquisitely hand-fabricated findings. In this interview, Lindner reflects on his life-long immersion in jewelry culture, the influences that culminate in his work, and the multiple meanings behind the title of his current show, Assemblage.

Adriane Dalton: Where are you from, and where do you reside currently?

Felix Lindner: I live and work in Erfurt, Germany, the town where I was born 43 years ago.

You are the son of a renowned jeweler, Rolf Lindner. This conjures up images of you, at age 5, soldering rings on your father’s lap—and listening in on jewelry talks when guests from Poland, Russia, or Hungary would visit. Is that how it happened? Do you feel you started your jewelry training before you learned to walk?

Felix Lindner: For sure I remember myself—at the age of 6—playing around and being amazed by my mother’s colored wooden necklace, made by Dorothea Prühl. Having this parental background was very influential and inspiring for me. At first it was the magical, mysterious workshop atmosphere; later on, as you pointed out, various contacts that my parents had as guests from all over the world. And though we were behind the Iron Curtain, it was not as hermetically closed as you might think! In 1984 we had a visit from Prof. Hermann Jünger, his wife, Jo Jünger, and some of his students. This turned out to be a heartwarming meeting with wonderful people, resulting in friendships and inspiration over the years.

Also, the community of people doing art jewelry in the DDR was extremely vivid and on a very high artistic level! Looking back now, I have to say that I feel glad and gifted that I had the opportunity to grow up in such an open-minded and art-dominated atmosphere as the one I experienced in my parents’ place.

Your current show at Galerie Rob Koudijs is entitled Assemblage. The word assemblage tends to conjure up an aesthetic that is a collision of disparate elements, but these works are very sleek and orderly. Can you talk about how you approached this term and how it translates in these works?

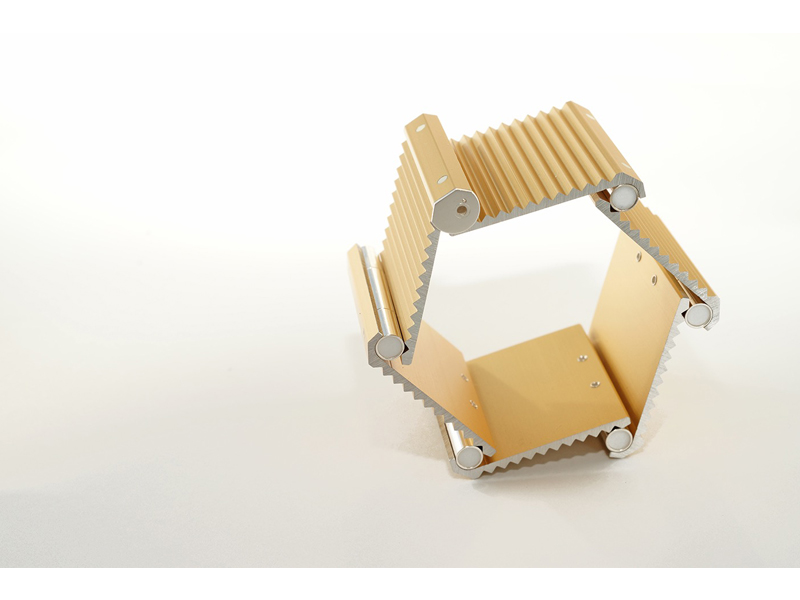

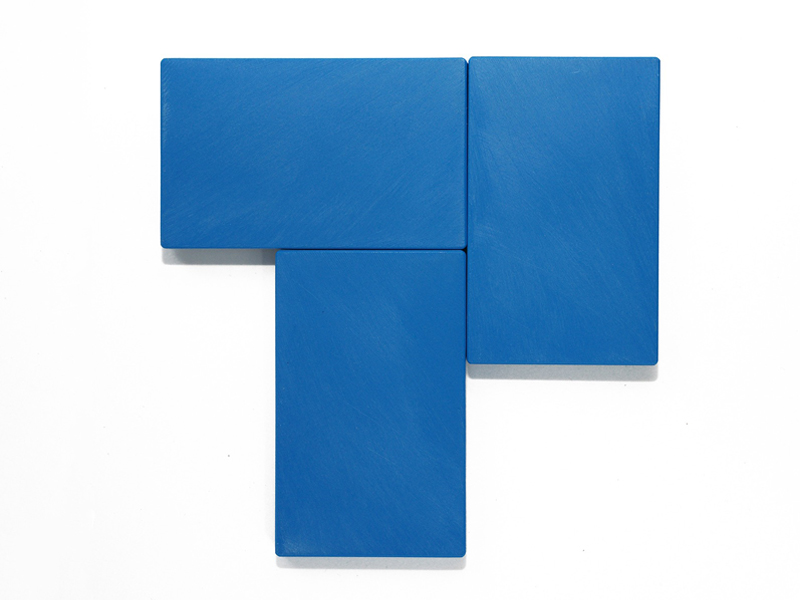

Felix Lindner: Haha, if you hear the term and you have a Kurt Schwitters work in mind, you’re probably mistaken. I certainly do refer to the art historical notion of the term, as the “mounting of found or prefabricated objects and fragments of material” and as a way of expression closely linked to Dada—a movement which had its 100-year anniversary just a few weeks ago! In fact, the show has many points in common with the title. For the series of bracelets entitled Home Sweet Home, I was selecting materials that are supposed to represent structures such as stone walls, wooden panels, or roof tiles. So here you have repeatedly disparate elements put together in order to create an abstract rhythm of color and shapes on the outside of the bracelet. On this level I stick almost literally to the notion of assemblage.

The show at Galerie Rob Koudijs is an assemblage in itself, uniting the different approaches toward contemporary jewelry that are found in my work. Getting back to Dada—an international group of young people escaping from World War I, meeting in Zurich, fighting the bourgeois, creating an art movement, being in constant exchange and collaboration with artists from the Dutch “de stijl” movement!—I have a lot of sympathy for their irony, playfulness, their way of undermining established concepts, and of course the aesthetic expressions that went along with all this.

Like some of your previous work, the new series prominently features plastic parts from children’s toys. In contrast to your previous work, your “contribution”—in this case the hinges and clasps—is now very visible. Are you interested in the contrast this creates—or in asserting your presence as an artist a bit more?

Felix Lindner: Right, it gives the feeling that I was asserting my presence as an artist a bit more—as you say. The bracelets have a different character from some previous works. I had a nice conversation with the owner of a Very Red bracelet about that. While Very Red immediately embraces the wrist and becomes part of the wearer—something she very much liked—the new pieces have a stronger presence. Things like this don’t really happen on purpose; it’s a side effect of a design process. Take the hinges that you mentioned, for example: You cannot talk ironically about bricks and all kind of construction materials and then use a nice hidden hinge. So, in consequence, hinges have to appear as 6-mm thick tubes on the front side.

The textural surfaces of several bracelets on display in Assemblage mimic wooden boards, bricks, tiles, and stones which are cut out from toy parts. It is tempting to see this as a reinterpretation of Art Deco craftsmanship (I am thinking of their use of shagreen, straw, eggshell, etc.) using the faux materiality of pop. Do you agree with this genealogy?

Felix Lindner: There’s certainly a lot of pop in it. The surfaces I choose are ready made. I find it quite amusing to contemplate the process of abstraction in the design of plastic toys, there’s much “ceci n’est pas une pipe” in it (imitating a medieval stone wall with an injection-molded piece of plastic). At the same time I value the high quality in color and materiality, I show it at the front side of the bracelet with a unique texture caused by a rough file.

Meanwhile, you are also paying homage to traditional jewelry (Empire) and minimalism (Assemblage 1). Is it difficult to reconcile your craft signature (hand-making and design skills) with artistic strategies (citation)? Do you know too much about jewelry?

Felix Lindner: This is an interesting question to me. During the creative process I never feel the need to look at other jewelry pieces—even if I have a rather good overview of the field. When I make jewelry I immerse naturally into a very intimate world. It has much to do with … “I’m doin’ just what I like to…,” to quote the Beastie Boys.

The bracelets are photographed flat as well as clasped. Are they made to be reversible, or only worn with the details on the interior as seen in the clasped image?

Felix Lindner: Initially I conceived the structures to be on the inside. It seems to me more decent to hide a story inside the piece. It’s a strategy that I have followed already for years with brooches and their backs. It is mirroring the ambiguous function of jewelry: a medium for communication with the person next to you and hiding personal secrets and meanings at the same time.

Where do you derive inspiration and how do you move from an idea to a wearable object?

Felix Lindner: I am very influenced by visual stimulations; I constantly have to look around. I catch details easily. Aesthetic facts play a major role for me: colors, shapes, surfaces, and atmospheres. Inspiration comes from industrial design, architecture, bandes dessinées (comic books), and a lot of music, pop culture, art history, and modernity. To move from an idea to a wearable object, there are basically two starting points. First, the excitement for a (probably found) object, which is a very archaic approach toward jewelry, or second, the vision of a piece that I would like to see worn by somebody. A lot of considerations and tryouts follow, to find the right solution for communicating my idea. Elaborating on the Empire bracelets took me about 10 years. Aesthetic points come first but there are also such aspects as expediency and reliability that count very much in my work. Again, I care a lot about how details and problems, even of seemingly minor significance, are solved.

In addition to one-of-a-kind jewelry pieces, you also have a limited-run production line, PE/AH, with French artist Samantha Font-Sala. How did this collaboration come about, and what does each of you bring to the design and production process?

Felix Lindner: PE/AH was born out of a dialogue about our ideas of how jewelry could look in a “pret-a-porter” context. The label was initiated in 2000 between Samantha and me. At this time we felt the need for jewelry that was not the cheap version of something else but an affordable, well-made, easy-to-consume, and elegant product.

To answer your question finally in a few words: Samantha has a perfect sense of style and I know how to do things well. Together we discuss each piece, propose ideas, know-how, and opinions. I believe that neither of us could do PE/AH on our own.

Do you differentiate between your art jewelry and the objects designed for PE/AH? Do you think that the manner of production changes the status of the object?

Felix Lindner: PE/AH is by definition a totally different approach toward jewelry. The main point in our work for PE/AH, that defines the status of the object in the first place, is the conception of the pieces and considering different aspects such as “… something that makes you feel that it is fresh and lovable and that your life will be all the merrier when you wear that necklace,” as Marjan Unger describes it in PE/AH Note from a fan.[1]

My own work refers far more to traditional values of jewelry. It is driven by the artistic need for expression of a very personal view and, yes, the manner of production naturally influences the status of an object.

I actually don’t think that a studio practice—where you are your own boss—is “freer” than a production practice—where presumably you must be more attentive to your client base. Do you find yourself less constrained in one of these two set-ups?

Felix Lindner: I totally agree with that! In the work for “Felix Lindner” I am much more constrained. As I mentioned, PE/AH is a playful conversation about jewelry and as long as the collaboration goes that way, it is definitely a vibrant project!

In the past, you have published some very exciting and intriguing catalogs. When is the next one coming out?

Felix Lindner: It’s about time …

Can you let us know which film, book, exhibition, or comic you recently came across that inspired you?

Felix Lindner: My brother recently made me listen to a re-edition of the album Rahsaan Rahsaan, a live recording from 1969 by Rahsaan Roland Kirk and the Vibration Society—actually one of the sound tracks of our childhood. It’s so amazing to listen to the brute saxophone and flute sounds of Roland Kirk … this is one of the sensations that inspire me!

Works in the exhibition are priced between 2,000 and 6,000 euros.