On April 26, 2023, we presented AJF Live goes to Mexico, where we met with Lorena Lazard. She introduced us to her own work and that of three other important contemporary jewelry makers in Mexico: Cristina Celis, Martacarmela Sotelo, and Raquel Bessudo. We recorded the event and posted it on our website. You can watch it by clicking here.

This interview served as a brief way to get acquainted with Lazard and her work prior to the AJF Live event.

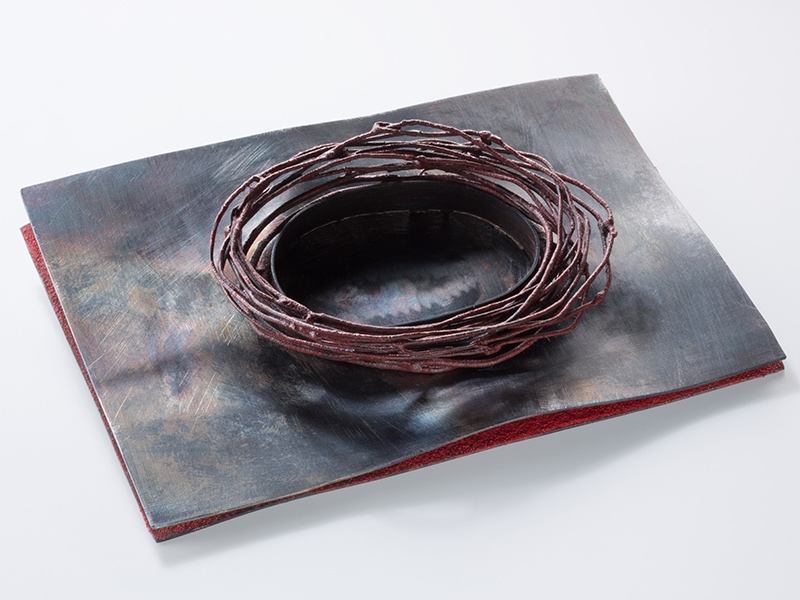

- Lazard seeks to unveil what can’t be seen but remains there to be discovered. The nonprecious materials she works with remind her that what shines is not always obvious. Sometimes you need to look for the soul in everything to find it.

- She uses soil in her work in part because it stores memories, giving an identity and a sense of belonging. It also serves as a metaphor for the substance we’re created from.

- Her work integrates elements from her various heritages and the sociocultural memories that accompany them. She tries to connect with a spiritual past, one that transcends time.

Alejandra Wolff: The pieces you produce have a direct relationship with the land, understanding this as a socio-affective and cultural link with the place one inhabits. How is this present in your work and what has the process been?

Lorena Lazard: Territory is related to emotions, memories, questions, and searching. It’s the physical, emotional, intellectual, and spiritual place one inhabits, but also somewhere we’d like to inhabit or that has been lost.

Using earth in my pieces has become a metaphor of this territory. The first time was when I created a piece that used soil from my father’s grave. He died suddenly when I was 15, and my memories take me back to that moment of hearing the sound of soil falling on his body during the burial. Many years later, I try to represent this chaotic memory, only now from a position of acceptance and reconciliation.

Soil today has many connotations, and using it is an act full of symbolism and meanings. I’m attracted by its opposite representation of life and death. The earth stores memories, giving me identity and a sense of belonging, helping me understand who I am. I’m searching for the meaning of my existence by using the soil as a metaphor of the substance that we humans were created from.

You’ve made a series of pieces in which you gather material and technical elements that include traces of a paleontological rescue and an archeological atmosphere. What place does your identity in the Abya Yala (Latin America) occupy as a referential or imaginary framework projected in these works?

Lorena Lazard: I was born and raised in Mexico within a second-generation European Jewish family. Though I grew up surrounded by images and figurative elements that fascinated me, I couldn’t relate to them. This generated a sense of duality in me. Now they offer me a sense of enormous richness. I have been able to integrate elements and cultural and social memories of these various heritages, achieving an identity full of elements that are the referential framework in which I exist and feel secure.

On the other hand, the past I want to connect with goes beyond the history of humanity. It’s a past beyond our understanding yet one we seek out, sometimes without knowing it. It’s a past that transcends a particular time, where there is no fragmentation and complete unity. It has a spiritual sense, where I’m seeking responses to these great questions that feel impossible to answer and which I wonder about: Why are we here in this world? Is there a reason for our existence? What’s the meaning of life? This provides my core, inner motivation to keep searching.

An important part of our Latin American cultural identities has been marked by colonialism and the violence that this historical process gave rise to. How can contemporary jewelry make our local cultures visible and contribute to the enhancement of their heritage?

Lorena Lazard: Although it’s difficult to pinpoint a single Latin American identity due to our region’s vast diversity, it is true that we are all living in a postcolonial culture rife with conflicts and inequality, but also one filled with a cultural richness that sometimes goes beyond us, and that makes us understand and experience the world in a unique way.

Ever since pre-Hispanic times, jewelry has played a profound and relevant role in our societies. It has always been present as a vital part of our languages of values and symbols. The challenge today is how to achieve this through contemporary jewelry.

In recent years, Latin America has produced—mainly in Argentina, Chile, Brazil, and Mexico—many movements that either independently or collectively have been essential for cultural expression, organization, and communication. Local contemporary jewelry has become mature enough to leave behind this quest for external validations and references, so it is an ideal time to turn inward—in fact, this movement is already underway. And from this place where we find ourselves, we can now ask what we have to say and how we can make a contribution. It’s about acknowledging ourselves. I feel very enthusiastic and excited to see what Latin America can contribute to our field over the coming years.

In the development of your work, and linked to the previous question, what projects have you developed that set up a dialogue with these issues?

Lorena Lazard: Mexico’s geographical reality gives it a very particular characteristic. As neighbors of the United States, our location has a unique effect—for better or worse—on the country’s economy, politics, culture, and society. As Mexicans, this relationship constantly permeates our daily lives, and we are very sensitive to it.

The border between our two countries is the place where this inevitable and conflictive relationship is more evident. I’d spent years thinking about it before it took physical shape in La Frontera, an exhibition I co-curated with the Velvet da Vinci gallery in the Franz Mayer Museum in 2013.[1] I wanted this exhibition to address important and difficult situations experienced by thousands of people on a daily basis, affecting them and everyone around them. I felt a need to humanize and tell stories that went beyond numbers and statistics.

Of all the different venues where the exhibition was held, the one in Mexico City made the biggest impact on me. Obviously because it’s my home town and it was amazing to see an exhibition of contemporary jewelry held for the first time in such a prestigious museum, but also—and especially—because the response from visitors exceeded all expectations: not only in terms of their numbers but also in the many reflections, questions, and discussions the exhibition generated. I believe it demonstrated, and demonstrated to me once again, jewelry’s power and immense capacity to convey ideas, spark conversations, and raise awareness.

Ten years after the original exhibition, I feel very excited that a revised version will soon be taken to the border region, El Paso/Ciudad Juárez and San Diego/Tijuana in 2023/2024.

Mexico has a long tradition of goldsmiths, from the pre-Columbian world to the colonial baroque and post-revolutionary modern art. How does your training and the development of your work fit into this tradition? What have been your references, and which artists have marked your career?

Lorena Lazard: Mexico has a longstanding metalsmith tradition. We’re experts in silverwork and we have amazing artisans and designers. It’s very strange, but in Mexico somehow everyone’s a jeweler. And this establishes preconceived ideas and expectations that are almost too deeply entrenched, virtually tattooed on our collective subconscious, about our understanding. What is jewelry? How should we see it? What’s it used for? And, of course, even now, what materials should it be made from?

From a young age I was drawn to jewelry and colonial art. In fact, the first items of jewelry I ever bought were some replica earrings from that period. But at that time, the idea of becoming a jeweler was far from my mind.

It was only when I went to live in the United States, where by coincidence I studied jewelry with Diane Falkenhagen (though I don’t believe in coincidence). This was my first reference to this world. Approaching it through university studies, from an artistic perspective, gave me a different understanding of jewelry from the outset. I doubt that I’d have been able to get here by taking any other path.

Over the years I’ve been in contact with many contemporary jewelers who have always impressed me with their generosity and honesty. They’ve undoubtedly been an enormous source of inspiration, especially Ramón Puig Cuyas. Within the art world, Antoni Tàpies has been a constant reference point, along with many contemporary Mexican artists, such as Perla Krause and Gabriel de la Mora.

When we talk about the relationship between memory and history, we face a narrative built, on the one hand, of testimonies, affections, memories, and forgetfulness, and, on the other hand, of documents, facts, and archives. I believe your work encompasses both scenarios. Your pieces form part of history and rescue what has been forgotten, focusing on the precarious and what has been discarded by luxury and power. How do you select your materials, and what criteria do you adopt when arranging and composing your pieces to account for both narratives—memory and history?

Lorena Lazard: My work is a reflection and an internal quest, where I try to find answers, especially to what defies explanation. And although I almost never find those answers, looking for them helps me transit from chaos to order. It is born more of a need to connect with the transcendental, with that spiritual place that seeks to show us something unknown about ourselves while allowing us to acknowledge the other.

My personal memory is a sum of moments that become my history. I realize that my personal memory is part of the history, and that history is part of my personal memory. Ultimately, everything is connected, based on that collective memory of uniqueness.

I’m interested in discovering what cannot be seen but remains there to be discovered. Among other reasons, that’s why I work with nonprecious materials, because they remind me that what shines is not always obvious, but that everything has a soul and sometimes you need to look for it in order to find it.

For some years now, we have been exposing inequities regarding the place of gender in public representation and demanding participation and inclusion in the cultural field. Where do you place yourself as a jeweler in these contexts? And is there anything in your work and/or your artistic practice that enters into dialogue with and addresses these issues?

Lorena Lazard: Gender issues have always been very important to me. Before entering the art world, I studied agronomic engineering and got a master’s in sociology, specializing in gender studies. In Mexico, as in the rest of the world, women still face many disadvantages and many changes are needed. As one of the most dangerous countries in Latin America for women, the situation in Mexico is dreadful. This is the nation that introduced the term “femicide” to the world, given the need to classify and denounce the murders of women motivated by misogyny and sexism.

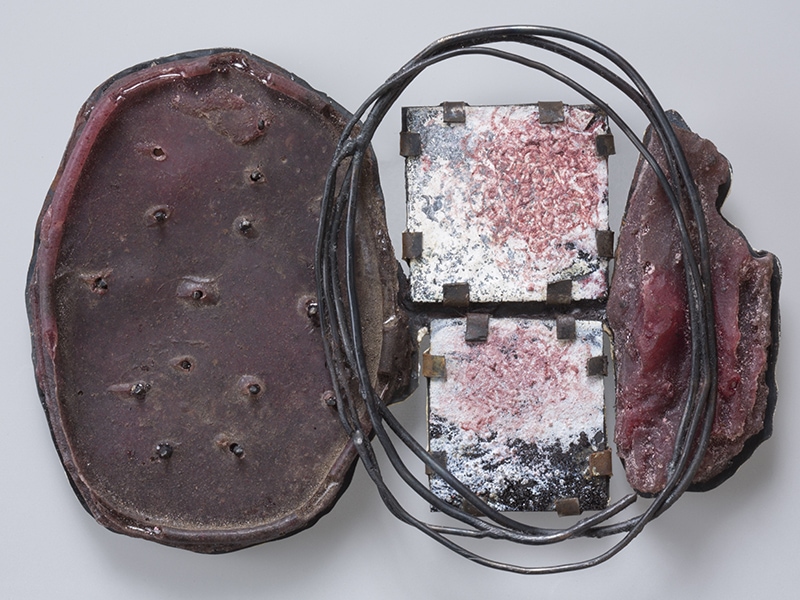

Some of my pieces want to reflect on the void left behind by femicide. These negative spaces cannot be filled; they represent a reality that will never be able to be restored and it is a reminder of the truth that cannot be erased and silenced. They are also based on a need to humanize victims and to move away from simply counting them as numbers and statistics. We don’t know their identities, names, or history. I’m keen for my work to help raise awareness about this situation.

You are a teacher. What principles of teaching and learning about jewelry do you think should currently be strengthened?

Lorena Lazard: I’ve taught in various capacities. It’s important to be sincere as a teacher, by sharing my own experiences. I want to convey my love and enthusiasm for the creative process. It’s vital to provide accompaniment in this process by expanding the mind, questioning, doubting, allowing for experimentation, often frustration, and learning by discovering your mistakes. Above all, I’m interested in helping all students to connect with themselves and gain self-awareness a little bit more each day through these processes. In 1995, after several years in the United States, I came back to live in Mexico, and I felt completely isolated from the world of contemporary jewelry. This was my initial motivation to create Atelier Lazard, which has become a space to learn, create, and promote contemporary jewelry in Mexico.

Many of the jewelers who studied at this school are now on the national and international jewelry scene. The school has also helped raise awareness and educate through various exhibitions, conferences, and with links to artists outside Mexico and organizations such as SNAG. I also coordinate the postgraduate studies program in Contemporary Jewelry, within the Fashion department at CENTRO University in Mexico City. This experience is inscribed within an academic and institutional sphere. In this program, most students are graduates with design, industrial design, architecture, and fashion degrees. I’m fascinated by their approach and ability to learn about the possibilities and scope of this new jewelry, which most of them do not know about beforehand, yet remain open and enthusiastic about experimenting with. Now it would be ideal to set up a contemporary jewelry program at an art faculty.

[1] You can read a review of this exhibition, published on AJF, here.