Chava Krivchenia: How does having a background in jewelry-making affect your curatorial approach with jewelry, or the jewelry that you select for the museum to acquire?

Carole Guinard: As a jeweler myself, I constantly ask myself questions about the use and the meaning of jewelry. I have been working in this field since 1979 and have met jewelers at the beginning of their careers; I have followed their evolution; I have sometimes exhibited with them. I share the same passion with them. I understand the same language.

Knowing how things are being made makes me aware of their quality. It also allows me to understand better maybe what the creator meant to say.

What is a jewelry work that consistently inspires you within mudac’s permanent collection, and why?

Carole Guinard: I have a special feeling for Cozticteocuitatl, by Otto Künzli. Cozticteocuitatl is an Aztec term for the yellow feces of the gods. In the simplicity and symmetry of these perfectly proportioned jewels, and in the materials used—gold and silver—they seem to hark back in time. Their shapes may seem archetypal to us, yet they derive inspiration from bits of information that the Western eye takes in daily, emanating from the folk culture or advertising of our consumer society—Mickey Mouse, Batman, or familiar logos like the McDonald’s “M” or Chanel’s double “C”s. Künzli also culls visual information belonging to our collective imagination. He offers us his series of emblems in the manner of an archaeological museum presenting its treasures.

What are a couple of jewelry pieces you’re especially proud of helping acquire for mudac’s permanent collection?

Carole Guinard: I am lucky to have discovered Julie Usel’s Generic Pearls, when she presented it for her diploma work at the HEAD – Genève (an art and design school that began in 2006 and is the result of a merger between the École Supérieure des Beaux-Arts and the Haute École d’Arts Appliqués). I was part of the jury and was touched by the simplicity and the cleverness of her work. This is a pearl necklace that looks like any conventional pearl necklace. But if you take a second look, you realize that it’s made of cellophane. In this work, Usel artificially copies the natural process of building a pearl. Each pearl is fashioned by hand, each new layer covering the previous one. She has subverted the string of pearls, a jewel passed from mother to daughter, a particular bourgeois custom.

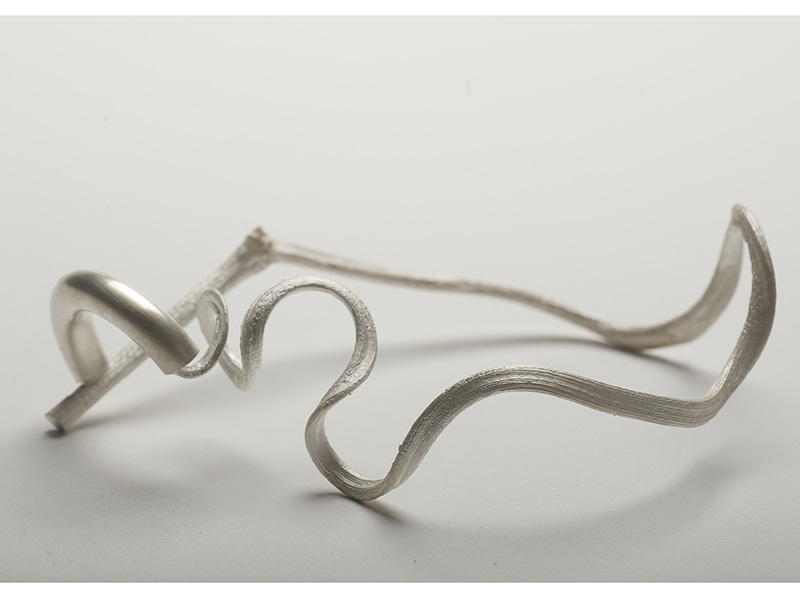

I organized an exhibition for David Bielander at mudac in 2015 in which he showed his cardboard pieces. His Cardboard (Watch) reminds me of the good time we had putting this exhibition together but is also representative of Bielander’s humor and his taste for surprises. Here’s a watch that looks like cardboard but is made of silver. The hour is set at 10:10, as on any timepiece presented in the showcase of a watch store. Bielander’s world is one of counterfeit and counter current, of destabilization and intriguing illusion.

The exhibitions that you’ve curated include jewelry but also photography and video imagery of jewelry. How do you decide what media of exhibiting benefits, or is most appropriate for, a jewelry piece?

Carole Guinard: When showing jewelry in a showcase, the body is always missing. Jewelry is not just a small sculpture, it lives on the body, it’s meant to be worn, it’s shown to the world on the wearer. So, whenever possible, I show pictures of the jewelry being worn.

How does the portability and wearability (constant relationship with body/bodies) of the work affect these relationships?

Carole Guinard: Jewelry is meant to be worn, so the body interferes in the choice of the shape of the work, its weight, its size, its material. Except for brooches, all other types of jewelry are in contact with the skin. Is it rough, is it comfortable, do I like to touch it, is it too heavy, too big, too small?

But the wearability is also an important point in the conception of a piece of jewelry, as this is how the work is going to be shown to others. Seducing or claiming personal status are linked to a piece of jewelry. What am I saying about myself to others when I wear a piece of contemporary jewelry? Jewelry is a symbolic sign.

You wrote, “A jewel is not just a decorative object or useless accessory. It is a field of infinite exploration that, thanks to the recovered freedom in this area since 1960, allows creators to question its meaning, function, and use, and to try out countless techniques and materials. It is a place to voice opinion that is close to contemporary art.”

What are some ways you believe that the intermingling of contemporary art and contemporary art jewelry (at mudac) affect the understanding of each field and enrich one another?

Carole Guinard: Contemporary jewelry speaks of the world, of politics, of human feelings, of transmission. If you put works side by side that say the same thing but in different media, they interact with each other. In fact, both deal with concepts that are translated differently.

Who are a few emerging contemporary jewelry artists you’re excited about right now?

Carole Guinard: I’m curious to see what’s going to come out of Hochschule Luzern since Christoph Zellweger took over the Design und Kunst department, but unfortunately, I haven’t yet had time to visit the school.

Would you please share or recommend something thought-provoking about the jewelry field which you have recently read, heard, or seen with AJF’s readers?

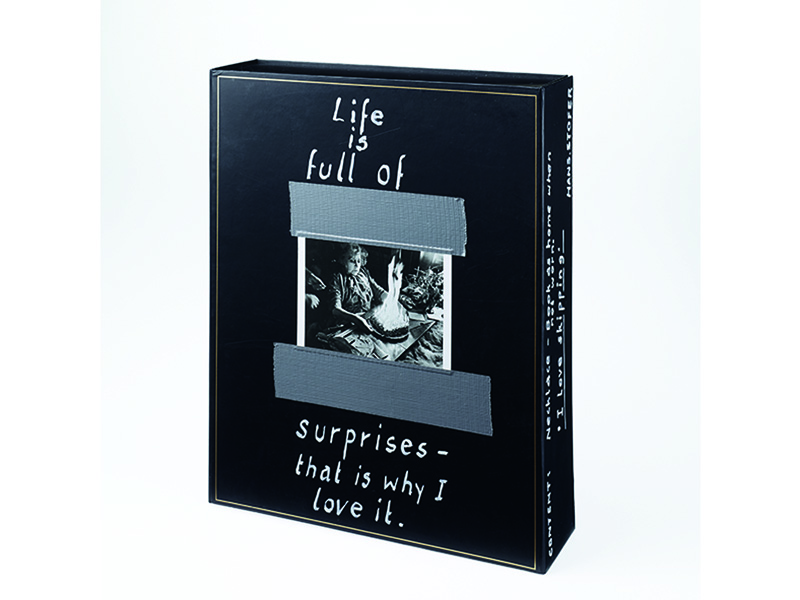

Carole Guinard: “Life is full of surprises, that is why I love it.” This is written on the box containing Hans Stofer’s neckpiece I Love Skipping, which is in our collection at mudac. This is just an everyday philosophy, not really thought-provoking…

Both your exhibitions From Hand to Hand and Ornaments from There, Ornaments from Here explore relationships in the jewelry world. How do you believe contemporary jewelry is able to particularly explore relationships?

Carole Guinard: In From Hand to Hand (2008), I was exploring the transmission of know-how, the transmission of a way of “thinking” jewelry. What is it that creates links between students and teachers, are they faithful or not to what was taught to them, what was the influence of a teacher on a student?

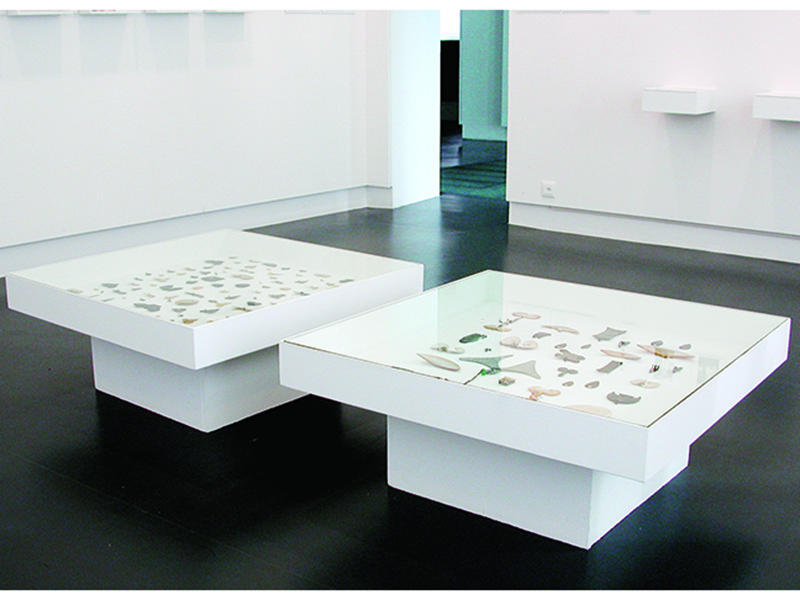

In Ornaments from There, Ornaments from Here (2000), the idea was to show how pieces from different origins could look quite similar in shape or the materials used but be completely different in meaning. It demonstrated how contemporary jewelry is an individual expression, how it claims an artistic status, how it freed itself from the tradition of conventional European jewelry and how jewelry from traditional cultures has a structured language, obvious to the entire community, that refers to the social system of which it is an essential aspect. In the West, since the end of the 18th century, jewelry has lost most of its social language to become more and more just a symbol of wealth. The only jewelry we still have that is worn to carry a message and that is understood by everyone is the wedding ring and religious symbols. Of course, jewelry is mostly signs, but they are different depending on the culture!

I don’t think it’s a particularity of contemporary jewelry to be able to explore relationships. Creating links is often a good way to make the public aware of differences or similarities, and this is how surprises occur. And what’s better than a surprise to open the eyes?