Historically, Guerrero has the rougher reputation—its mountains were home to Lucio Cabañas and his guerrilla in the 70s, for example—but Michoacán is now renowned for drug cartel activity, and during the week before I left for the coast, had figured prominently in the country’s headlines. Federal agents and reputed cartel operators had faced off in shootouts in different parts of the state over several days with consistently fatal results. The creation of unsanctioned community police in many townships (formed by locals to replace inefficient or corrupt law enforcement and offer some protection against organized crime extorsion) and the subsequent need of the federal government to reassert its presence with a show of force, had certainly played a role in these confrontations, but it was unclear to what extent.

The proximity of the violence was made manifest by the last bridge I passed on the highway on the way in, before reaching the seaside. It had witnessed the first ambush, the one that had set everything off. I passed it again on my way out, hoping that even though the exhibition closed on that very day, I would be able to see at least some of the pieces before they were packed away and sent to San Francisco for the second leg of the project. What most occupied my mind, however, was concern for those of us travelling back from the coast, which I tried to ease by telling myself that lightning never struck the same place twice.

My trip home was uneventful, though I later learned that a high-ranking Navy officer had been killed in northern Michoacán around noon. So it wasn’t until two days later, while looking at the miniature silver AK-47 assault rifles portrayed by Elizabeth Rustrian and Edward Lane McCartney in the exhibition, that brooding thoughts of the past week-and-a-half finally coalesced and pushed forth two conclusions. First, that I’d been quite concerned about seeing an actual AK-47 up close while crossing Michoacán. The Kalashnikov rifle, or cuerno de chivo (goat’s horn) as it’s known here because of its shape, has become closely linked in our minds to the cartels. And second, that to think today of the border between Mexico and the United States—of la frontera—is all too often to think of drug traffic and the violence it leaves in its wake.

The border, of course, is not all about drug traffic. However, the fact remains that to the north is the world’s largest market for drugs and Mexico’s principal supplier of guns. Many firearms that are illegal here can be purchased with ridiculous ease across the border. Of the four northern border states, only California imposes a waiting period between purchase and delivery. In a country where 33-percent of the population lives on less than five dollars a day,1 the wholesale of illicit drugs (dominated today by Mexican drug cartels) produces earnings of anywhere between 13.6 and 49.4 billion dollars. The bodycount of the “war on drugs” launched in 2006 by ex-president Calderón currently stands at around 100,000, and rising. 2

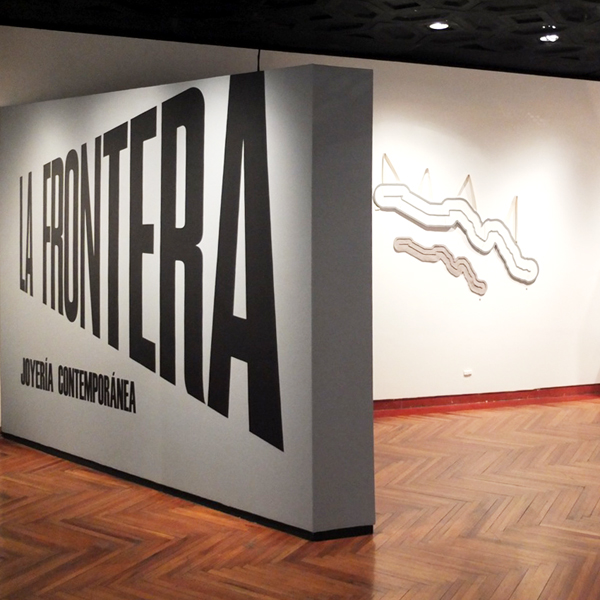

I did not see the exhibition as such. It was in the process of being packed away by the time I got to the Franz Mayer, so I could not appreciate its museographical intent. Thanks to Héctor Rivero, the museum’s director, and Ricardo Pérez, head of collections, I was nonetheless able to see many of the pieces up close, without intervening barriers, as perhaps no other visitor could. My first glimpse was of curious objects on metal shelves or on top of crates, surrounded by packing paper and plastic. Ricardo then suggested that we take advantage of the afternoon light in one of the museum’s upper corridors, which overlook the central patio of this magnificent colonial building. He proceeded to bring the pieces out, one after the other, and place them with great care on a bench covered with white wrapping paper where I could inspect them at close range and photograph them. I’ve tried to get a sense of the pieces I did not see from the catalogue, and thus of the exhibition as a whole, but my appreciation is biased by my close, rather intimate contact with the ones I saw first hand.

Back to the AK-47s and their grisly resonances. One of the exhibition’s necklaces, Rustrian’s Cruce de armas, features quite an array of these and other guns suspended from a golden barbed-wire collar. A figure, reminiscent of what strikes me as a Renaissance cherub, sits on top of the weapons, at center, with a blank cube for a head and a green jewel in its raised right hand. In the author’s own words, it represents “the illegal arms passing between the US and Mexico with the unrecognized consent of both governments.” McCartney’s position regarding his If Bullets Were Jewels gun brooches is anything but cavalier: “I was concerned with memorializing lives and events destroyed and marked with violence through the traditions of Victorian mourning jewelry.” As a longtime resident of Texas, he’s seen the border change over the past 30 years, and concludes that “human lives have become the disposable commodity of the new merchant class in the illegal drug and munitions market.” A chilling assessment, followed up by a rather surprising question: “What if bullets were jewels? Would anything change?”

The question doesn’t make sense to me. I, for one, am not prepared to wear one of McCartney’s brooches. Not after one-too-many youngsters who consider it hip to sport a machine gun tattoo on their arm. Or after seeing the pictures of the cache of actual decorated weapons seized by Mexican police in 2010 in Jalisco, which included a gold-plated AK-47 (real size and usable, thanks very much), and various handguns inlaid with diamonds, among other niceties. So often one step ahead of the police or the military, it seems that the cartels also have the lead in the process of turning guns into ornaments and ornaments into guns.

As the traditional crossing points for undocumented workers have become progressively harder to cross, with more and more walls, border patrol agents, or robot drones, migrants have chosen to risk other, harsher terrains, such as the Sonoran Desert. According to the latest figures, the number of illegal crossings has fallen lately, but deaths from thirst, exposure, or accident have risen. 1 Kevin Hughes addresses the hardships involved in these life-threatening treks with his necklace, which bears a pendant made from the handle of a plastic water jug, an eloquent reminder of the life-or-death importance of drinkable water.

Awareness in Mexico has been on the rise concerning the deadly danger of crossing the other frontera, the lower one with Guatemala. Immigrants from farther south must traverse it and successfully navigate the whole of Mexico in order to reach the promised land. The news reports every day on people from Honduras or El Salvador found dead and buried in ditches or suffocating in the secret compartments of trailers. The most notorious example of the perils involved is the train known as La bestia (The Beast), which crosses Mexico from south to north, carrying hop-on immigrants from Central America along its route who are subject to all manner of extorsion and abuse from official and nonofficial sources. 2 Many of them don’t survive, and Jette

Even El Santo—Mexico’s legendary wrestler and pop icon, featured in movies and comic books from the 1950s to the 80s and vanquisher of Martians, zombies, and vampire women—is rendered helpless by the plight of the border. “Adored, but at the same time detained,” as he’s held behind silver bars in Jacqueline Roffe’s El luchador 1. The characters drawn by painter Mark Clark for Nancy Moyer’s reversible neckpiece Border Fence Series: Border Scenarios might seem cartoonish, but they actually pay tribute to pre-Columbian codices. They include a hapless immigrant on top of a fence caught between border police, swat-like forces, and skin-head sicarios or hitmen, who carry a bodiless head and—what else—an AK-47.

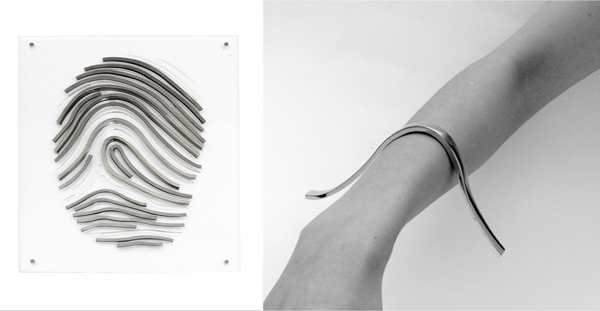

Can jewelry offer a form-specific perspective on the complex issues surrounding the border? Benito Taibo writes in the exhibition’s catalogue that contemporary jewelry can be “conceptual art that uses the body, the wrist, the shoulders as its canvas.” I agree that some pieces are conceptually quite eloquent. The problem, as is often the case with conceptual art, is that the conceptual coin often drops after reading the artist’s statement. Many are deadly serious, as could be expected. One example is Holland Houdek’s Laryngectomy Tube, which reflects on how medical supplies have a hard time crossing in the opposite direction, from the US to Mexico. Some works are conceptually simpler and not as intellectually stimulating, but these perhaps more adequatly fulfill Taibo’s second condition—that they can actually be put on, maybe even pleasurably.

A few pictures of people donning some of the jewelry were included in the exhibition, yet the pieces ultimately linger in the imagination as disembodied presences. This doubtless has to do with how I experienced them, but some of the pieces would probably have a hard time getting their point across outside of the protected context of a museum exhibition. Meeting both of Taibo’s criteria—wearability and artistic pertinence—seems in some cases an unreachable ideal rather than a feasible goal. And, as the miniature weapons made us consider, whether one would accept wearing the pieces in the first place hinges on whether one interprets them as indirect glorification of, or warning against, violence. One of the painful but necessary lessons of contemporary Mexico is that in order to heal the effects of violence that violence cannot be kept hidden. It must be made visible so that we can face it as a society. After all is said, some of the pieces of La Frontera jewelry exhibition have managed to find a place in my personal notion of that arid and history-rich landscape that is our northern border; a territory which plays such a defining role in giving Mexico its particular—and sometimes terrible—place in the world today.

La Frontera was curated by Mike Holmes and Elizabeth Shypertt, founders of Velvet da Vinci, and Lorena Lazard, from Mexico City.