Laura Rysman: Do you make a distinction between designers who consider themselves artists and those who work in a commercial setting? What is the difference for you between jewelry designers/artists who fabricate their work—studio jewelers—and those who have work produced, or even mass-produced?

Alba Cappellieri: Like Bruno Munari said, artists work for themselves or for a small elite, while designers work in teams for the whole community, with the mission of bettering a product—whether aesthetically or functionally. Designers don’t concern themselves with one-of-a-kind works like artists do. Art produces unique pieces, while design, at least in theory, produces in series. Reproduction is a part of the design process. Art is free of practical goals, seeking instead to satisfy a cultural ambition.

Gijs Bakker, the master of Dutch jewelry design and founder of Droog, said in 1978, “When I design a piece of jewelry, I always have production in mind. I’ve never been interested in things made by hand; I don’t share that fascination. Whether it was made by me or by a machine, it’s only the idea that counts.”

Whether you agree with Munari and Bakker or not, it’s undeniable that art and design are two distinct categories, even as they are starting to imitate each other. The designer thinks to make people feel something; the artist feels to make people think. It is the designer who creates products that integrate technical considerations—of materials, techniques, prototypes, fabrication, and production—along with economic considerations.

In 2013, you curated an exhibit for the Triennale of Milan entitled Italian Design Meets Jewelry, where movements of design, and not jewelry, were the focus of the show, though it was a jewelry exhibit. How do you see jewelry intersecting with the field of design? Is there a special interaction in Italy, where both fields are so close to the artisans and producers who have traditionally made the pieces?

The design world has never concerned itself with jewelry, never considering it as a worthy arena to try. Designers work with incredible changes in scale between architecture, interiors, furniture, lighting, and objects, but jewelry has always been blatantly absent. With just a few exceptions, jewelry hasn’t aroused interest among 20th-century designers, perhaps because the modern rationalist ideology excluded everything that lacked a social function or a populist ideal, and the designer’s idea of producing in series runs counter to the exclusivity and distinction that establishes the value of jewelry.

In other countries, designers were freer to experiment in different areas, but in Italy a pseudo-moralism impeded designers from concerning themselves with ideas, like those of ornamentation, that were not considered socially useful. Certainly, the great Italian designers created jewelry as well, but only as gifts for relatives and friends, like the engagement rings of Gio Ponti and Roberto Sambonet for their wives, the numerous necklaces that Gianfranco Frattini made for his daughter Emanuela, the jewelry of Sottsass for Fernanda Pivano, or the rings Sergio Asti created for his wife Mariangela Erba.

Italian design favors evolution rather that revolution; beauty and quality over abstraction or concept. The fusion of jewelry production with Italian design represents a great hope for the near future—one full of promise because the transfer of expertise, materials, techniques, and processes are the foundation of innovation, and can revitalize Italian jewelry.

You recently curated an exhibit titled Around the Future: 3D Printing for Jewelry. What does 3D production mean for jewelry designers today and for the future? Will this art become more interactive with the end wearer? How do you see 3D technology impacting the creation of jewelry?

Alba Cappellieri: New materials and technologies kick-start innovation—products and production evolve, developing the economy, and by extension, the competitiveness of business. Jewelry, among the products that accompany our lives and our bodies, is among the most static: the techniques and materials are the same as in the past, as are the formal references and styles. It’s only in the 20th century—the “fast century”—that technical, material, and sociological innovations have impacted jewelry, transforming its meaning as much as its form.

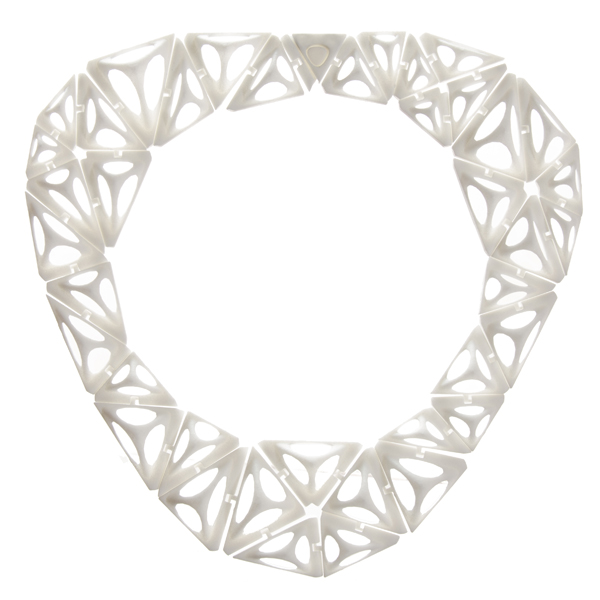

Technologies like rapid prototyping, rotational molding, selective laser sintering, sheet metal forming, stereolithography, CNC routing, laser cutting, and acid etching will be widely available through outsourcing, and can be applied to jewelry production, making it possible to create new shapes and finishes. 3D printing, an additive method of production by which objects are created with stacked layers of materials, makes it as economical to create individual objects as to create thousands, so it’s well-suited to the needs of companies and designers. 3D printers also offer the ability to print and assemble parts composed of different materials, using diverse physical and mechanical properties in a single construction process, and to create models whose appearance and functionality are very close to those of finished products. The future of jewelry will be drastically altered by 3D printing, allowing for personalization and variations that were previously complicated and expensive, and changing the design process as much as the production process.

The 35 international designers represented at the exhibit I curated in Vicenza showed jewelry that would be impossible to create using casting molds or other traditional methods. New technology is bringing digital ideas into the real world and it will, with time, become more accessible, intuitive, and easy to use.

What do you see changing in the world of jewelry and jewelry art?

Alba Cappellieri: The future of jewelry is in technology. Jewelry has never experimented with technology, which is why it has evolved so slowly. Such cross-pollination is new for jewelry, and it’s happening because of fabrication and commercial necessities, not because of an experimental drive. Denying progress and its prophets —new materials and new technologies—could be understandable as long as jewelry was confined to traditionalism, but now the art of the goldsmith is becoming contemporary, and wearable technologies have shown the world how the body can transform itself into an exhibition site.

Jewelry is by definition a “useless” object, holding no function apart from creating beauty and representing power or social status—symbolic functions but certainly not utilitarian ones. Just like for fabric, jewelry can incorporate smart materials or sensors that give new meaning to jewelry, transforming it into a functional object. Marshall McLuhan, the Canadian intellectual and philosopher of communication theory, predicted in 1964 that technological evolution would represent an extension of the human body. Our previously useless jewelry will integrate, using wearable technologies, new practical functions capable of improving our lives and, in some cases, even saving it.

From medicine to sports, from childhood transport, tourism, and leisure to bridal wear or banking, the possibilities are extremely diverse. New sensors will enable “use” of the jewel to monitor our health status, inform the restaurant of our food intolerances, guide us in a new city, and help us find a soul mate, our glasses, keys, cat, or child. Technology is shaping a new anima mundi and jewelry is at a turning point.

What is your next project?

Alba Cappellieri: My next project, the one I’m most excited about, is the opening of the Museo del Gioiello di Vicenza on December 19. It’s the first museum dedicated entirely to jewelry in Europe, and one of only a handful in the world. It’s also a wonderful example for Italy, a country on the point of ruin because of political problems, of how public and private entities can work together successfully. The Fiera di Vicenza (which holds VicenzaOro, the international jewelry trade show) supported the initiative in collaboration with the city of Vicenza, which provided the prestigious Renaissance-era Basilica Palladiana to house the museum. Patricia Urquiola has designed contemporary interiors and display cases for the new project, maintaining the integrity of (renowned Renaissance architect and area native) Andrea Palladio’s structure. The museum will host Neolithic pieces alongside 3D-generated jewelry—adornments ranging from ancient to contemporary will sit alongside each other to illustrate the many semantic complexities of the world of jewelry.

What is the museum’s scope and mission? In curating the museum, how do you respond to historical trends, innovation, and jewelry as an art form? Is the museum a didactic tool?

Alba Cappellieri: In overseeing this project, I didn’t want to use historical chronology or a series of styles to talk about jewelry, or try to present a comprehensive overview of jewelry—I wanted to arouse the visitor’s curiosity and sense of wonder, to educate and even entertain the visitor, and to begin by asking, what do you think jewelry is?

The museum is divided into nine rooms, each with a distinct thematic idea and an individual curator (they are Aldo Bakker, Gijs Bakker, Bianca Cappello, Franco Cologni, Deanna Farneti Cera, Graziella Folchini Grassetto, Stefano Papi, Maura Picciau and Paolo Maria Guarrera, and Alfonsina Russo and Ida Caruso). I wanted to allow each room to express the vision of different international curators because the world today is governed by image, and there is a need to return to the deliberation of thought. Every curator makes a selection, which is by nature incomplete, but behind each choice is the reasoning of an individual curator, so each room takes on a very strong interpretive character.

The museum’s exhibition begins with magic jewelry: Talismanic pieces were the first jewels, existing apart from the notion of precious materials. The second room is dedicated to symbolic jewelry because, historically, jewelry has held a powerful symbolic role, representing wealth, status, or even memories, religious identity, or the talents and capabilities of a region.

One room is dedicated to jewelry in the world of design, created for production and using no precious materials, and another room is dedicated to fashion, which has always had a close if complicated relationship with jewelry. The icons room exhibits pieces that have established new jewelry vernacular with their styles, shapes, and materials. And the ninth room is dedicated to jewelry of the future, with new techniques and materials.

The exhibit will last for two years, after which the themes will remain but new curators will be invited to interpret them so that the people of Vicenza and other visitors will be interested in returning to the museum. The mission is not to give a thorough overview, like what happens in so many museums today, but rather to embrace old and new together, and to show the richness of a variety of ideas.