Michigan-based artist Aaron Decker engages with potentially ominous imagery, such as military medals and hand grenades, by playfully reimagining them into innocuous forms disarmed through exaggeration and reconfiguration. In this conversation, Aaron reveals the deeply personal origins of his creative practice and contextualizes the militaristic imagery that underlies the works on view in his first solo exhibition, Derby and His Badges, at Ornamentum.

Adriane Dalton: Where did you grow up, and where do you currently reside?

Aaron Patrick Decker: I grew up all over the place. My father was in the military, so we spent time on bases, alongside other military families. I’ve had a hard time answering questions of origin—it’s like telling the story of who I am since I can remember. For a long time, the answer was often the place I just left. Today, I would say I am not from anywhere other than the United States, although I currently live in Ypsilanti, Michigan.

How did you arrive at jewelry-making as your primary mode of expression?

Aaron Patrick Decker: I spent time in my grandfather’s clock shop in a small town called Madison, Maine, and got a lot of exposure to this kind of work, its scale and intricacy. I began to explore jewelry-making after my grandfather passed away during my third year at a university studying English literature.

This is still quite a raw spot for me. I was very close with him, despite the limited time we shared. Both my father and I took his loss very hard. One thing led to the next, and I exited my studies as an English major and enrolled at a small private school, Maine College of Art, to study jewelry and metalsmithing. It has snowballed since then.

I fell in love with jewelry, arriving at it with the desire to be connected to someone I lost. That drives me even now.

You recently completed an MFA at Cranbrook Academy of Art, where you received the 2015 Mercedes-Benz Emerging Artist Award and the 2015 Marzee Graduate Prize. What impact have these accolades had on your post-graduate career?

Aaron Patrick Decker: I am so fortunate and thankful to have received these recognitions—they brought exposure that’s difficult to come by as a young artist. They’ve allowed me to participate in the Künstlerhaus Bethanien International Residency, where I forged amazing connections and learned a lot about myself post-graduation. Receiving these awards also keeps the fire under my ass lit. I don’t make for awards, but the insecurity that creeps into the studio as a young artist goes between a wail and a whisper because of these accolades.

Slowly, I’m learning to control it.

In 2012 you received a Windgate Fellowship that provided resources for traveling to Europe, during which you participated in artist residencies and conducted a series of interviews with jewelry artists, publishing many of them on Art Jewelry Forum. What artistically and socially did you gain from that time spent?

Aaron Patrick Decker: It was not my intention to leave school with only one way of making. The Windgate Fellowship offered exposure to artists about whom I had only read, such as Kadri Mälk, Tanel Veenre, Leonor Hipólito, and Cristina Filipe. I had the chance to see their studios and engage with their practices. To sit with makers and hear how they got to where they are—it was all important. The connections I made have sustained me and truly molded my practice.

Derby and His Badges is your first solo exhibition. How many works are exhibited, and how long did you spend preparing for the show?

Aaron Patrick Decker: There are 37 works exhibited. They are the result of about a year’s work and preparation.

Adriane, what benefit does an audience gain from this knowledge? Is it important to know?

I think providing a temporal context helps to inform audiences about the labor that goes into making a body of work. I find this to be particularly useful in regard to jewelry because the process behind the work is not always apparent in the finished pieces.

There seem to be three aesthetic factions within this body of works: the soft, sculptural fabric badges; the flat, illustratively engraved pieces; and the matte, structural works such as Long Boat and Derby. What separates these works, and what connects them to one another?

Aaron Patrick Decker: I love the term “factions!”

I could tell you what separates them and connects them—it would most likely be formal at first, such as shape, color, treatment of form. What really unites the works is this overall feel, a naïve insecurity, and an oddness. Someone asked me if I used found objects, or if these objects were meant to “quote” them. I am trying to make toward an object, toward a badge … each of the works is trying to capture itself in a funny way, like recollecting its beginning with not much matter of the end.

What do you see that connects them or separates them?

I think the works are connected by playfulness in the form and scale but are separated by materials. There’s an underlying somber militarism apparent in pieces such as Badges for Toy, Campaign 2 that lists “army blanket wool” among its materials, and in the resemblance of Leftover Toy, for example, to objects of war (in this case, a hand grenade). Is this militaristic theme something you’re indeed consciously trying to communicate through the forms and the materials?

Aaron Patrick Decker: I am connected to this imagery—I grew up around it. A weapon, for example, is such a complex device. Its power, its ability to hold an image for face value, when it is simply an object, is astounding. Image impacts on our psyche.

There is also the badge or medal. A person can hide behind a badge. They are shields and, funnily enough, you can see this in their forms. I’m interested in a type of camouflage which is not just covering oneself in bushes, but occurring all the time. The man putting on his suit, the jewelry on the woman’s ear, the abundance of toys in a lonely child’s room. There’s more trauma in something trying to hide, rather than being itself.

You have been very nimble in making subtle references to a culture of awards, decorations, insignias, leaving quite a bit of space for people to make their own connections. Were you tempted, during the design process, to produce more explicit statements?

Aaron Patrick Decker: I am absolutely tempted. I sometimes want to be more direct, to have a thesis statement laid out for the work. It would make it easier to make, no? Sometimes, the desire to shout from rooftops what it all means would be wholly satisfying. Sadly, I don’t know quite exactly what it all means. I have interests, paths to travel, corners to explore, but, no, I can’t put my finger completely on it.

Sitting in my studio, I sometimes think more didactic work would be great for content—powerful direct hyperboles of weapons, badges, tanks, and guns. But, in the end, each piece is a sort of end unto itself. They know when they are done, and if I try and force it on them, they have a tendency to fight back and not want to be finished. I push some pieces harder than others; we will see how that comes up in the next group of works.

I’m intrigued by the exaggerated pin mechanism on brooches such as Backing and Brave. Much like the pin in Leftovertoy, or the lens in RED, it seems to hint at functions that have become dysfunctional motifs in objects that look deflated, or maladjusted. Two questions: Have you taken on the precarious position of the artist who makes things that purposefully “don’t work” and broadcast their tentativeness? What reactions do you think these objects will generate when worn?

Aaron Patrick Decker: Have I taken the position you describe? Yes—they are functionless functions attached to deflated or maladjusted forms. To ask whether this choice is precarious is to ask whether all pin backs must be serious, whether these and similar mechanisms in jewelry are somehow off limits, relegated to strictly functional tasks. Function, after all, has such an overbearing righteousness, that to deflate it, to make it flaccid, to mark it as too big for its own function, renders it funny. It’s akin to a penis—this object and symbol of power and virility. When flaccid, it’s functionless, funny, and odd.

When these pieces are worn, I hope people react. I hope they see what you see, and are irresolute.

How important is wearability to your work?

Aaron Patrick Decker: These pieces are foremost jewelry, and so all are wearable. When you make work in reference to the imagery of badges, the body is very important. With that said, if a body of work required me to go out of “wearable” work, it could happen. Integrity is important in work.

Whose work do you admire, both in the field of jewelry and more broadly, and why?

Aaron Patrick Decker: There is always a shifting lens, looking at others’ works, admiring them, listening to music, feeling moody about it all. I tend to gravitate toward things that push me, sustain a mood that I find productive, or are wholly satisfying to look at.

Anke Huybnen for a work that offers a gendered yet personal critique. Tino Sehgal for a sustained perspective on human experience via the medium of performance art. It is some of the best work I have experienced to date. And, guiltily enough, Van Cleef & Arpels.

In terms of reading, I have always loved The Great Gatsby. I just started the Regeneration Trilogy by Pat Barker, and Barbara Kingsolver’s works. I gravitate toward sentimentalist perspectives, trying to reclaim, own, or be something you cannot be. These archetypes have always run into my work.

There are too many things I love, like, and enjoy. Keeping those sources close is also important, so I don’t like to divulge too much.

Work in this exhibition ranges from $500 to $2,200.

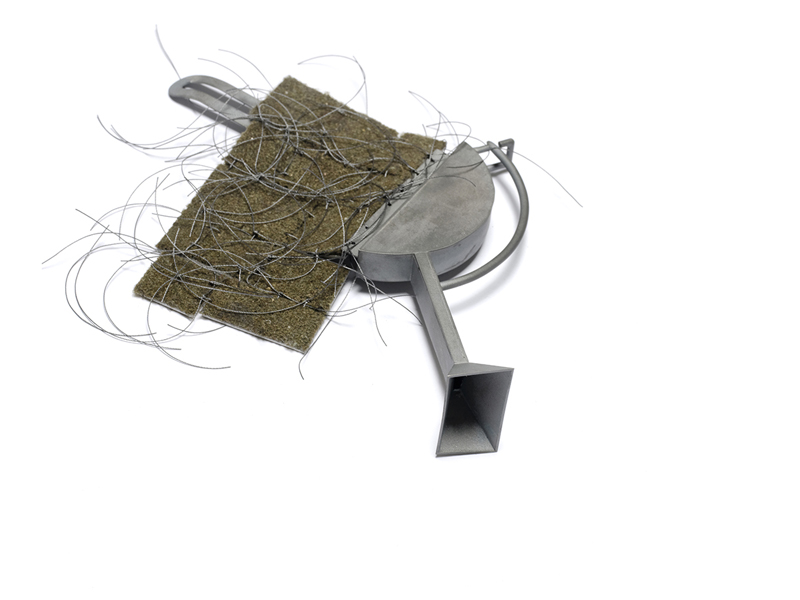

INDEX IMAGE: Aaron Patrick Decker, Aim Fire, 2015, brooch, nickel, army blanket, steel, 178 x 64 x 25 mm, photo: courtesy of the artist