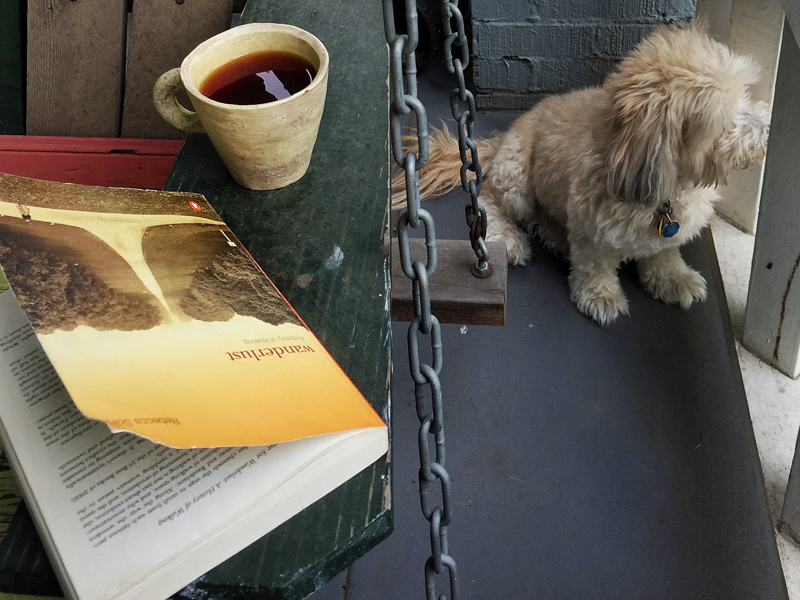

For me, the summer seems infinite at the start, and inevitably screeches to an end after our annual family camping trip in the first week of August. For the past 15 years, this week tolls the last gasp of the season, making us scramble for a bit more sun, to cram in one more book, and to reluctantly prepare for the start of school. I chose to end summer with Rebecca Solnit’s Wanderlust: A History of Walking in the hopes that it will offer an armchair extension of the glories of summer when the rains (hopefully) hit Portland, Oregon, this fall. I relished Solnit’s The Faraway Nearby last year, and marvel at her ability to infuse her writing with thoughtful passion, politics, and personal experience while simultaneously linking history and landscape, philosophy, and literature— regardless of the writing format. Whether a social media post, long-form article, or book—she is fearless, complex, and clear.

“Everyone walks,” Solnit writes in her acknowledgments, adding further that “the history of walking is everyone’s history.” Slowness and simplicity surface repeatedly in this rich examination of the mundane. The first five of 17 total essays, grouped into a section titled “The Pace of Thoughts,” for example, unfold with a rhythm and density that I can only consume in portions of a chapter at a time. Solnit takes notice of how the rhythm of walking frees the mind to think. She discusses a variety of kinds of walks— meandering, political, pilgrimages, marches, and fundraising walk-a-thons—connecting each type to her personal passions, philosophy, and the environment. Solnit’s text makes images, sensations, and connections tumble rapidly into my head, leaving me no choice but to close the book and leave it every few pages. I find myself pushed into bodily action by her writing: I have frequently closed the book to take a walk so I can connect the range of her ideas to the flood of thoughts in my head. These walks bring visibility to the place of walking in my own life—disconnected personal experiences connect with Solnit’s text. Walking is the way my grandfather taught me during our visit to India in 1977; we walked through the Tungarli Hills and Lonavala discussing anything and everything, turning the landscape into a classroom. (I’ve tried adult versions of this. Walking meetings are a trend that failed for me while working for a museum—no pace works well for note-taking.)

Late summer walks at home are sharp reminders to never take ambulatory freedoms for granted. Walking was nearly absent for much of our trip earlier this summer to South Africa, where almost every person actively dissuaded us from exploring Johannesburg and Durban on foot. As Solnit writes, “Perhaps walking can be called movement, not travel, a certain kind of wanderlust can only be assuaged by the acts of the body itself in motion, not the motion of the car, boat, or plane” (page 6). Our “home” for one night was Satyagraha House, a small boutique hotel and museum housed in the former home of Hermann Kallenbach. It is from this house that Mahatma Gandhi walked to a communal farm every day, leaving at 2 or 3 a.m. to make the journey—and where he developed his theory of passive resistance. Solnit refers to him as the pioneer of political walks. The irony of our being temporarily housed within a building once inhabited by Gandhi and now enclosed by a wall and high-tech security fence exemplifies how restricted mobility curtailed our touristic wanderlust. The spatial theatre of our experience was controlled by circumstances, and left us feeling at moments like the animals confined within the fenced safari park at which we spent a week. I’ve never felt more like a visiting tourist.

“Walking shares with making and working that crucial element of engagement of the body and the mind with the world, of knowing the world through the body and the body through the world,” writes Solnit (page 29). As I finish the book—and the summer—I cannot help but wonder if Roseanne Bartley has read this book, and how much I want to take a walk with her and talk about it.