I am already looking forward to the 2nd Lisbon Contemporary Jewellery Biennial! Exceptionally organized, manageable for visitors, and with just the right mix of events (17 in total), it created an uncluttered conceptual space in which to present fresh work and ideas within the contemporary jewelry field. Commencing the week of September 13 and ending November 21, 2021, just as the world was in the process of being (or protesting being) vaccinated, this was not an easy affair to pull off.

Indeed, during the planning phase, no one knew what the status of the virus and its many variants might be by the time of the opening. Shipping was (and remains) in shambles; the ability to travel was uncertain; and it could have been perceived as insensitive to bring people together in such a physically menacing time. Insightfully, however, the organizers, PIN (Portuguese Association for Contemporary Jewellery)—led by Cristina Filipe, Marta Costa Reis, Isa Duarte Ribeiro, and Luís Torres—in partnership with MUDE (Museu do Design e da Moda, Coleção Francisco Capelo), Museu de São Roque/SCML, Museu da Farmácia, Research Centre for Science and Technology of the Arts – CITAR/ Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Brotéria, Sociedade Nacional de Belas-Artes, Ar.Co–Centro de Arte Comunicação Visual, Escola Artística António Arroio, Instituto Cultural Romeno de Lisboa, as well as with private galleries and artists who organized exhibitions as part of the official program, understood the importance of safely coming together to reflect on the tragedy that befell the world, how we are surviving it, and the need to re-experience our community through seeing and talking about jewelry.

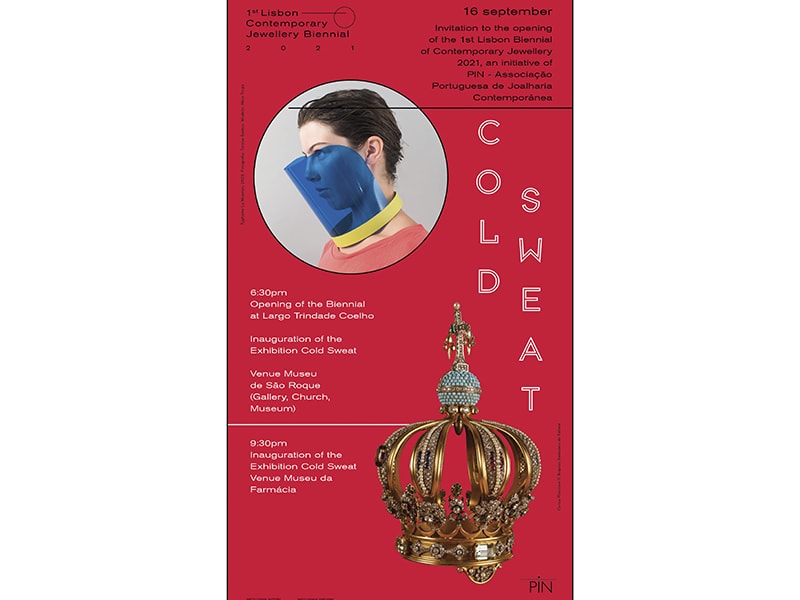

The biennial was structured around the themes “The Body,” “Fear,” and “Protection.” How fascinating to compare notes with friends from across the globe through discussing the work! It was a perfect salve for the isolation and troublesome feelings we have been collectively experiencing. Decisions such as titling the biennial and its main exhibition “Cold Sweat,” (coined by Kadri Mälk) and placing jewelry in conversation with religious objects at the Museu de São Roque (a cloister with a collection Portuguese sacred art) and the Igreja de São Roque (the baroque Jesuit church that is attached to it), as well as with medicinal objects at the Museu da Farmácia, a space dedicated to the history of pharmaceuticals, helped to encourage these conversations. With artist talks, gallery and museum shows, an academic symposium, master classes, and exhibitions, the power of contemporary jewelry to stimulate meaningful dialogue and help us deal with the dystopian subjects that dominate today was impressively clear.

Some background: In 2017, Cristina Filipe, organizer and curator, won the first Susan Beech Mid-Career Artist Grant, which ultimately played a role in bringing this event to fruition. In 2019, AJF traveled to Lisbon for a presentation of Filipe’s book based on her Ph.D thesis, Contemporary Jewellery In Portugal: From the Vanguards of the 1960s to the Early 21st Century which had been sponsored by the prize. For that occasion, AJF organized a five-day trip to visit artists, collector homes, workshops, and some museums, including Filipe’s exhibition at the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation where she put contemporary jewelry in conversation with pieces from their stellar collection. The success of the visit created the motivation to make the biennial a reality, and PIN set a date for the inaugural to take place in 2021. As the world became engulfed by the pandemic in 2020, the theme for the first edition became obvious.

As it turns out, with its small size and supportive community, religious background, arts institutions, and complex relationship with the meaning of jewelry, Lisbon was the perfect setting for any biennial to take place during COVID times. Not many places have a pharmacy museum or churches that will allow you to place contemporary jewelry next to healing potions and spiritual relics that are hundreds of years old!

While there are far too many stand-out moments to mention in this short article, some include

- A tribute to the recent death of Valeria Vallarta Siemelink at Museu de São Roque, with a necklace by Alcides Fortes and Siemelink from 2003 made of found wood and broken glass from the destruction of a house that was bombed during the Iraq War

- Caroline Broadhead’s Preservation and Shielding installation, also at the Museu de São Roque, that put pearls encased in glass in conversation with a photograph, by Daniel Blaufuks, of empty jewelry displays, indicating the toxic nature of our bodies interacting with our environments and the resultant empty storefronts that dominate the landscape

- Silvia Beildeck’s A Flea, shown at the Brazilian exhibition Ferida Aberta by Grupo Broca. In this work, a series of creepy and ominous golden “bugs” were placed around the head of a woman in a photograph to symbolize the anxiety of disinformation, half-truths, and hallucinations that have plagued social media and our ability to distinguish facts from fiction

- Manuela Sousa’s 2020 object, a box with a glove at the Igreja de São Roque with names written on it of those who have died during the pandemic.

- The historic installations at the Museu da Farmácia, with mannequins wearing contemporary “ink blot” brooches by Agnieszka Knap

- The colloquium presentation by João Neto about protective objects in the pharmacy museum collection

- The artist talks at the Jewelry Room, where Ruudt Peters, Patrícia Domingues, and Tanel Veenre got personal about their lives and practices

- And the jewelry retrospective of Portuguese sculptor José Aurélio, whose stellar work was almost unknown to the general public before this moment

Portuguese sculptor José Aurélio and his jewelry work at his retrospective, photo: Eduardo Sousa Ribeiro, courtesy PIN Work by José Aurélio, photo: Eduardo Sousa Ribeiro, courtesy PIN

In retrospect, the themes of “The Body,” “Fear,” and “Protection” were not only necessary for the moment but also revealed a broader way to think about the meaning of jewelry beyond a western secular mindset. Cultures that embrace jewelry as protection, as amulets, and as central to survival, both spiritually and physically, think of it outside the mnemonics of class, wealth, and women. In the US, the relentless play with these themes keeps the conversation exclusive, to only those who “get” jewelry in the same way we do.

As we look to diversify our field, it’s worthwhile to not only think of the kinds of people who make contemporary jewelry, but also to consider the meaning of the work and how it reflects a diversity of beliefs about jewelry around the globe. Against the Lisbon backdrop, the “Cold Sweat” biennial accomplished just that. It presented a jewelry field with a broadened conversation that was relevant to a diverse group of makers and wearers.

I would like to give a special thank you to PIN, namely Marta Costa Reis, for applying for a grant from FLAD – Luso American Development Foundation so that I could attend this important event.