In Pakistan and in India, there is a word—darshan—for looking at images. It comes from Hinduism, and refers to indigenous receptivity of sacred images. Darshan is visual receptivity, an intense absorption. Whether it’s jewelry, shrines, cinema, this indigenous absorption, a culturally specific receptivity to imagery, wraps around all forms of visual sites.

The entropy of jewelry and objects in Pakistan exists and resides throughout the country: Their weight, material, form, and function are manifestations of the sacred, or an attempt to understand the sacred. Sacredness, like an air of its own, was already present in the soil. The objects and jewelry seem to have come into being from this cultural consciousness. Decades later, dug up and removed from the soil, the objects are encountered in the Lahore Museum, known as “Ajaaib Ghar”—ghar meaning house and ajaaib meaning strangeness, wonder, curiosity. This strangeness emanates from and is an intimate part of sacredness, and inseparable from the language of ornaments and artifacts in Pakistan.

Pakistan’s jewelry history is embedded in two distinct trajectories from two different time periods. One type, from the sites of Mohenjo Daro and Taxila, is humble and primitive in its appeal. The second unfolds power and prestige mounted in the precious stones and meticulous craftsmanship from the eras of the Maharajas and Mughals.

The civilization of Mohenjo Daro, the first to lay down the concept of urban planning in the subcontinent, understood a particular void: a compulsive, soul-searching need to make forms that could exist as documents for self-expression, religion, and entertainment, as status and social markers. To sanctify the concept of a city that had just been built, the artisans carved and cast their materials and metals to allude to the most revered beliefs of their city. The creation of these makings, their appearance, was to determine what kind of a culture could possibly be formed. Perhaps making was a search for a culture itself. From pottery, tools, and seals to terracotta bangles, ornamentation was a language of both desire and need. And the discovery of materials like copper, lapis, and carnelian in the soil, backed by the people’s sophisticated engineering skills, allowed for a collaboration to open up. Without the materials, the objects would never have come into being; the materials themselves intuitively determined for the artisans what could be produced.

By contrast, the material culture in the era of Maharajas (meaning “great king”) and Mughals, dating back to 500 years ago, saw long ropes of pearls cascading in varying lengths, huge emeralds foiled and mounted with pure gold strips, and diamonds in massive sizes set atop feathered turbans. The finest and rarest gemstones were acquired from the Indian treasury (which also forged long-term partnerships with the Cartiers), to be transformed into opulent jewels. The jewelry—especially gemstones, their sizes, hues, rarity—pouring in from Golconda to Kashmir was part of a larger narrative: of royal status, court culture, patronage, and politics and power.

The astoundingly rich visual index of jewelry in Pakistan permeates through deserts, the alleys of cities, and shrines. In Cholistan, Pakistan’s largest desert, married and unmarried “water girls” are distinguished by white glass bangles in full and half arms. The pure white bangles transcend their own circular forms, becoming an immortalized artifact belonging to the ridged, untouched sand dunes and the folklores and cultures that have evolved through the very landscape. Dotted across cities of Pakistan, artisans seated on the floor work on traditionally low jewelry workbenches, tracing patterns from archived photocopies of traditional ornaments, pressing down and bordering tiny spheres of granules along strips of filigree for final investment soldering.

In March 2018, Lahore witnessed a radical transformation in the field of jewelry when the city’s fine diamond brand, Aliel, collaborated with VASL, Pakistan’s largest “fine arts” collective. This saw the brand’s preciousness shift into the world of fine arts. In the showroom was a curation of 11 pieces: an outcome of in-depth research between artists and fine jewelry manufacturers. Led by Aliel and Sheraz Faisal, a Pakistani artist, the VASL-Aliel collaboration unfolded the artists’ work practices: a slow revealing of how the artists’ processes and pieces conversed with the precious materiality and techniques of fine jewelry.

Why must a fine artist meet a fine jewelry manufacturer? The VASL-Aliel collaboration sought how fine jewelry can allow its skills, techniques, and precious metal and gemstones into the realm of fine arts. Both disciplines, especially the traditional branch of miniature painting in Pakistan, share a parallel sense of time-consuming labor and craftmanship. The fine arts drawings are imbued with multiple meanings: they are manifestations of sublime aesthetic experiences and subjectivity. Fine jewelry, in its absence of those experiences, appears through “value,” embodied in gemstones and metals. What then becomes the purpose of drawings and artworks here? The artworks become not about meanings, but about how the elements of drawings can become an integral part of fine jewelry. In this process, precious metals and gemstones translate into color, line, and other elements of paintings. Is fine jewelry’s meaning then gained in how it becomes a “fine” drawing?

The necklace Two Loves, by Ghulam Mohammad, hangs on the body like a painting when worn. Mohammad belongs to the province of Balochistan, in Pakistan, but relocated to another city, Lahore, to begin his BFA. This resulted in a widening sense of cultural gap and a severe language barrier. He had to acclimatize to Urdu, Lahore’s regional language, and discovered how language has the ability to divide and unite, to create new meanings but also to limit communication. In his work, Mohammad cuts hundreds of individual letters from discarded Urdu notebooks, pasting and arranging them on wasli paper (a special handmade paper) into dense, carpet-like creations. These “carpet-drawings,” whereby he deconstructs a paragraph or text, separating language from itself then putting the letter back again, speaks of meditating upon his paradox with language, its hierarchies, and limitations.

In his two pendant series, Two Loves I & II, Mohammad turns to the intimate personal-political letters of Pakistan’s revolutionary Urdu poet Faiz Ahmad Faiz as his solace and medium while unfolding his language crisis. Both pendants incorporate intricate collage of texts on wasli paper mounted in oval-shaped gold bezels. Ovals have been used across cultures, both in European miniature portrait jewelry and in India and Pakistan in miniature paintings. Perhaps the portraits and texts become an affirmation of each other: texts denote the void through the absence of a portrait, while language—the layers of letters, burdened and illegible—becomes the revealed identity and portrait.

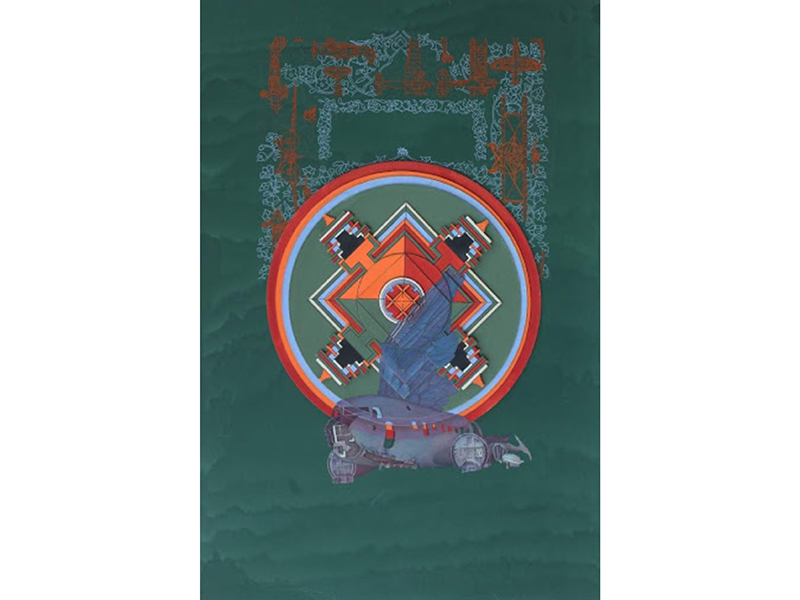

Yasir Waqas was forced to abandon his desire to become an artist and instead trained as a pilot and certified aircraft mechanic. He felt constrained as a pilot, but the fascinating details of aeronautics triggered his imagination to pursue miniature painting as an expression of this conflict and confusion. His earrings, consisting of artworks he has executed with gouache on wasli paper, carry two significant images, one a mandala executed through seven layers of papers, and a bird in another. The bird and the mandala, through its cosmic presence and layers, reveal Waqas’s innate conflicts and constraints as he questions his deeper existence.

The mandala also resembles the markings on runways that identify where to land planes. Framed with soil-colored brown diamonds, the earrings act as a fine, delicate glimpse into our identities and circumstances: How we individuals take flight from one situation to another, how we position ourselves, where we land.

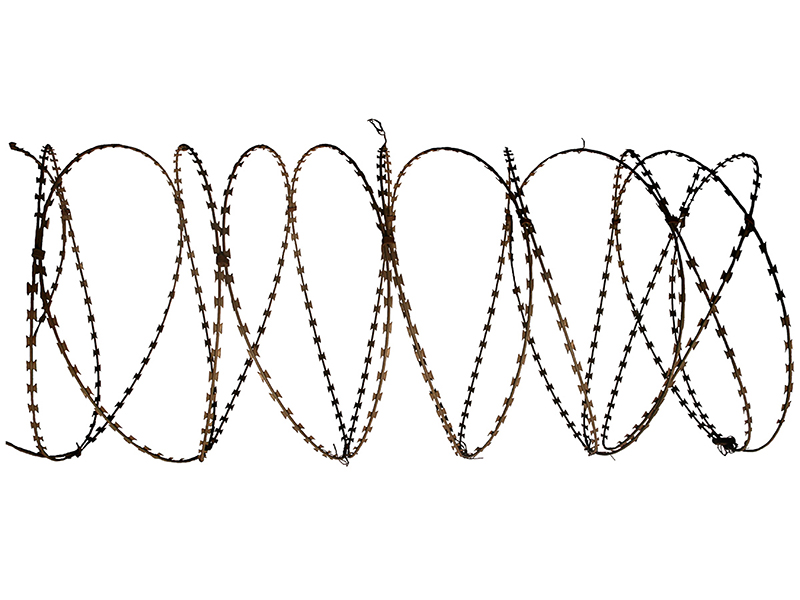

Farida Batool’s art is a critique on the visual culture of Pakistan and the West. Aliel and Faisal reconstructed Batool’s powerful pieces Dark Gajre (Dark Garland) and Us Shehr Mein Mohabbat (Love in This City), from 2010. In her works, rose garlands and barbed wire fence not only carry close similarity in form, but also become “borders”—a barrier or a separation. Positioned next to each other, they also become an affirmation and truths for each other. In the Aliel showroom where her piece was installed, I witnessed a wall where jewelry transitioned back to the source from which it came: her archival prints (shown immediately above) mounted on the walls. In Dark Gajre, a garland traditionally worn on the wrist in Pakistan and India, known as gajras, is stretched across the wall in the manner of barbed wire, becoming a restricted landscape. Nearby, the Oblivion choker—an 18-karat twisted gold “barbed” wire “fence” suspended around a deep blue velvet strip—sat on a pedestal, emerging as a silent echo to the city’s landscape, which changed overnight in 2015 due to terrorism.

Barbed wire against a velvet strip—the velvet here becomes a strip of sky or a black ground. In this instance, the choker becomes an object in a changed landscape. With six strings of Burmese rubies hanging below the neckpiece, evocative of crucifixion and the Western nostalgia associated around it, we can wear what the artist saw in the length of few particular seconds or the frame of a night.

The jewelry of Shehnaz Ismail, a textile artist, depicts her intimate engagement with the loom and the materiality of fabric as seen from a personal, cultural, and political perspective. The 18-karat yellow gold wire represents a heddle, a thin metal wire on the loom which separates the warp thread from the passage of the weft.

Textiles carry and embody a language different from metal and stone. As a garment and material, textile is aware of its own fragility. In Shehnaz’s textile piece What They Have Done to My Land, various acquired fragments of cloth are wrapped up into bundles like the soft containers for carrying goods when people used to walk on foot. These shrunken bundles are mapped out and placed on the trajectory of the thin tapestry, appearing as a parched layer of the artist’s memory bank, while addressing a bigger narrative: that of migration after her country’s partition.

In her Chilmaan earrings, the wires, conveying the thinness of thread, echo Ismail’s personal and cultural practice of weaving, and also her vulnerability. Forming themselves into a scattered knot above, they guard the different weights and sizes of the pearls within. Pearls symbolize seeds, as a hope for a devastated land.

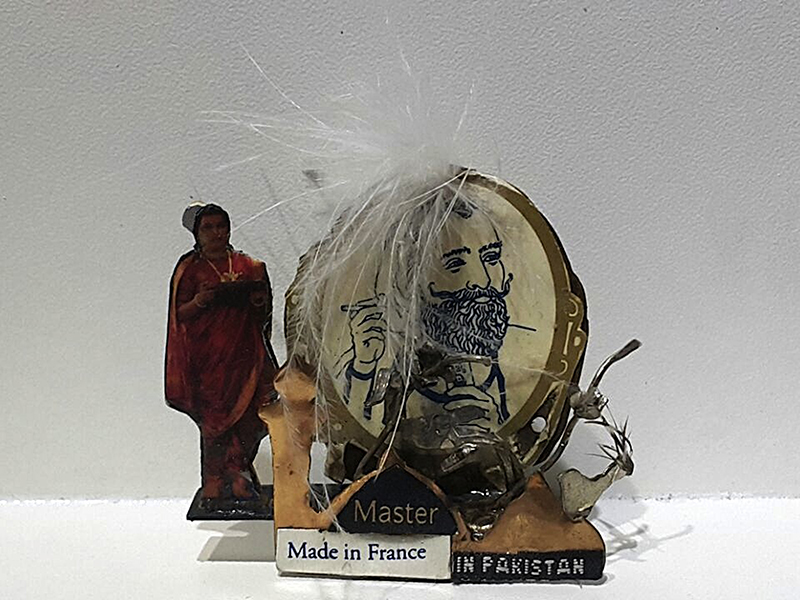

For Masooma Syed, jewelry is more than an ornament or a commodity. For her, the material is paramount: the materials, organic and inorganic, act as portrayers of her childhood memories, of conflict and the daily dilemmas of life and cross-border marriage. Jewelry, across societies and cultures, has always been seen as redeemable wealth, a display of socially meaningful codes. For Syed, the materials—a heterogeneous choice sourced anywhere from the human body to the kitchen, and including hair, dry chiles, used perfume bottles, and packaging materials—become an investigation into how jewelry can go beyond the idea of a commodity once it’s detached from its familiar codes, traditional materials, and meanings.

The materials, through their temporality, textures, and the forms transforming into “otherness,” gauge Syed’s emotions, her shifting self and identity. The pieces tell stories in which her diasporic identity creates new bridge or borders; where objects like bottles or chiles transform into displaced self-portraits, and “barcode” gates appear as almost totemic souvenirs of distance and closeness. It’s a story of the intimate and the public, bordering on self, home, marriage, and the two countries she belongs to, India and Pakistan. The familiar materials, things, and places in her objects are partially removed from their contexts and locations. What appears is a new place, a new location marked, created, and altered by the self.

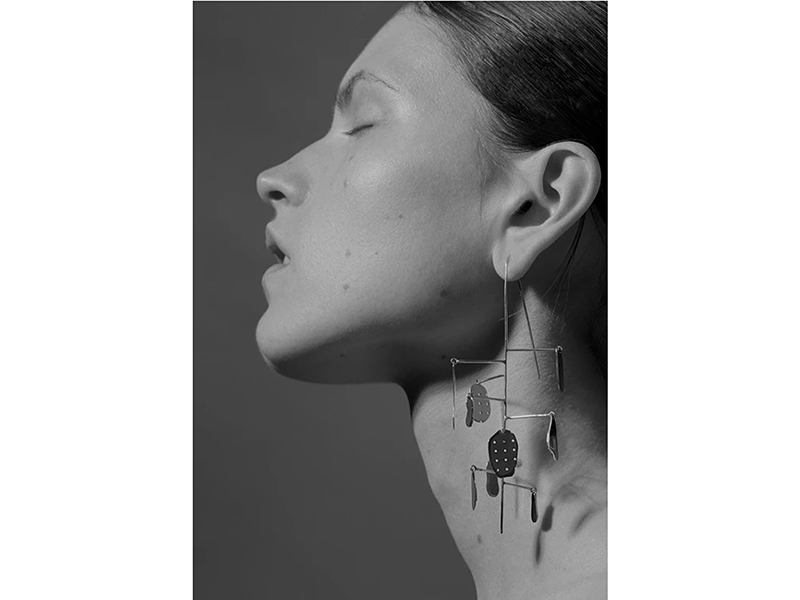

Zohra Rahman, a graduate of London’s Central St. Martin, relocated back to Pakistan with a vision to reinvent the traditional apprenticeships community. Her idea is to transform the discipline of silversmithing in Pakistan by completely breaking away from the conventional Eastern motifs. Playing out only in silver, Rahman’s inspirations are varied, stretching across technology to nature to Malevich’s abstract paintings. She sketches out amorphous forms that appear banal; they seem unfinished yet are portals into our everyday objects and interactions. From butterfly wings to shower hooks to traditional Arab arches (mehraabs), Rahman’s forms cross over with Calder’s mobile sculptures, becoming androgynous and genderless.

Once cut out in silver and placed on the body, the reflective surfaces open up another dimension: the forms mirror back the body and the garment. It is in this process that the pieces’ boundaries dissolve into the body and vice versa, opening up an atmosphere that is both visceral and futuristic.

The corpus of works discussed above is an initiation: to recognize and research on the possibility and existence of contemporary jewelry in Pakistan. After having completed my metalsmithing MFA at the Cranbrook Academy of Arts, I now teach Thesis in the jewelry department of the Pakistan Institute of Fashion and Design, in Lahore. This meant a re-study of how and where historical affinities sustained in materials, techniques, and artifacts are decoded and transformed into new objects and meanings when negotiating with self (the maker), artists, or in light of topics, whether from a historical past or contemporary present. The visits to our department of two international artists, Patricia Domingues and Karin Roy Andersson, in 2018 and 2019, generated a new space that carried multiple meanings of extremely critical value. Reaching for artists’ works while working on their own topics and creations gives my students the opportunity to arrive at and feel material’s innate sense of being, interpreted by the artists. The students and makers momentarily forget their topics and then bring them again at some point of viewing.

During the Lahore city walk conducted with Andersson through the theme of her work—repetition—the city became a projection of repeated elements or motifs, stacked up with each other. Encountering both this and Domingues’s Anthropocene-centric approach toward materials, we became aware of other possibilities that a topic or materials contain. These acquired insights gathered from workshops feed into materials and making, inviting a reconsideration of what Pakistan’s jewelry and its value is, beyond the scope of traditional ornaments. As my professor, Iris Eichenberg, once remarked, contemporary jewelry, when placed on plinths across borders, is not so much about a cultural belonging or an artifact but the questions and meanings we form around them.

Pakistan’s contemporary jewelry is a discipline and a narrative under development. As local institutes, galleries, and residencies become more inclusive for contemporary jewelry dialogue, it feels stimulating to see the course this discipline takes: from the culture of outsourcing, roaming across bazaars to find the right artisans with skills, to the bench as a research and production space, oscillating between a heritage of old techniques and new materials and ideas.