This essay was first delivered as a talk at SOFA NY in May 2011.

The Museum of Art and Design’s exhibition, Crafting Modernism: Midcentury Art and Design (opening in October 2011) features over 20 jewelers. Some are well known, such as Alexander Calder, while others have been resurrected from obscurity and brought forward for re-evaluation. Those represented in the show reveal that jewelers, like many artists in the exhibition, came from a range of disciplines. Some were trained in an academic setting; some, such as Sam Kramer, were largely self-taught; others hailed from the world of painting, sculpture and design.

The title of this talk was taken from the irrepressible Sam Kramer. His early Greenwich Village gallery was the center of activities both surrealistic and fun and he advertised his work as suitable for people who are ‘slightly mad.’ Kramer briefly studied jewelry with Glen Lukens in California. After a few years of travel, when he learned about gemology and Navajo culture, Kramer opened his gallery on Eighth Street in New York. From the start he worked with such unconventional materials as geodes and taxidermy eyes, used silver in a drip fashion and favored oddly compelling anthropomorphic and erotic shapes. All were calculated to startle and attract customers.

In the vanguard of studio jewelers, Kramer opened his gallery in 1939 and his work reflected the surrealistic developments then pursued by Salvador Dali, Max Ernst and Yves Tanguy. All employed elements of surprise and unexpected juxtapositions in their work. Kramer grasped the wider implications for jewelry from an early date, creating wall mounts so that his jewelry could be enjoyed, whether worn or not.

Other well-known pioneers included Ed Wiener and Art Smith. Wiener, a butcher’s son who discovered jewelry after taking a general crafts class at Columbia University, launched a highly successful business in New York and Provincetown, Massachusetts. Smith, another Greenwich Village artist, was involved with the world of dance. This gave him the profound insight that the body is an armature for ornament. His large, sensuous, form-fitting shapes were all about line and the human body. As a recent exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum has demonstrated, Smith’s work is more desirable today than ever before.

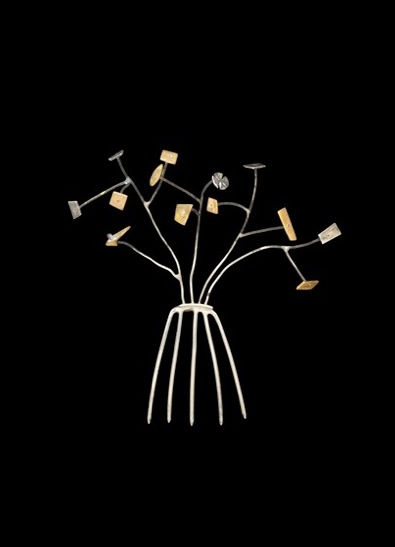

In the world of design, Harry Bertoia is best known for his Knoll designs such as the Bird ottoman and chair of 1952, included in Crafting Modernism. Bertoia explored aspects of the grid motif in furniture, sculpture, and jewelry, as seen in an early hair ornament.

Enamel became a significant method of ornamenting jewelry by the 1950s, thanks to technical advances in the field (chiefly owing to new, inexpensive kilns) and a renewed interest in historic works. The Museum of Contemporary Craft (later the American Craft Museum and today’s Museum of Arts and Design) mounted an important enamel exhibition in 1959. A select group of artists were invited to create works for this special occasion. John Paul Miller, master of granulation – where fine granules of gold are adhered to a surface without solder – emerged as an enamelist of great promise. Silversmith and jeweler Margret Craver participated in the exhibition, offering her first reinterpretation of an ancient technique called en résille. Craver had experimented for years to develop enamel that was free of the metal substrate typically required in the firing process and in which colored and metallic elements could freely float. The jewel-like centerpiece of Craver’s hair ornament was the first proof of her hard-won success.

From the postwar years through the 1960s, the most avant-garde jewelry was notable for its freedom of expression, relation to international artistic developments and experimental nature. Today, we recognize this marvelous efflorescence as the first flowering of the studio-craft movement.