In the summer of 2019, Naiza Khan’s work appeared in the inaugural Pakistan Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. Her solo show, Manora Field Notes, was widely lauded as the perfect debut for Pakistani contemporary art at this international forum. I had the pleasure of seeing Manora Field Notes firsthand at a later showing, in Lahore, Pakistan. Khan’s project is a response to more than a decade of close interaction with the ever-changing coastal landscape of Manora, a small island off the coast of Karachi, Pakistan.

Through her multidisciplinary practice, Khan investigates the nuances of life on Manora. In her work, the small island archipelago becomes a lens through which we might examine concerns ranging from ecological to sociopolitical. Here, issues one may think of as disparate, such as colonialism and climate change, meld together into a tapestry as complex as the human lives of which they speak.

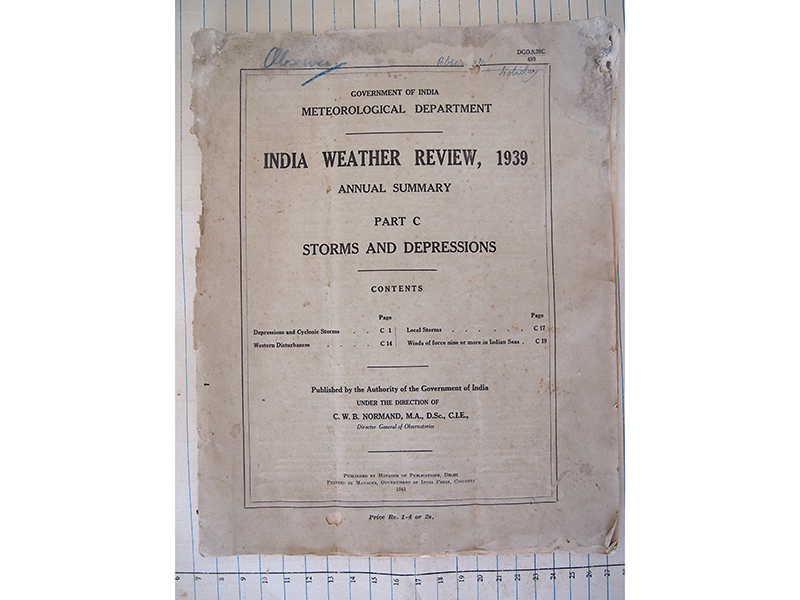

The work that captures the most attention, titled Hundreds of Birds Killed, is a sculptural installation based on an archival document that Khan recovered from the ruins of an old British weather observatory on Manora. The document, Indian Weather Review, 1939, contains a summary of weather calamities that occurred in coastal cities across India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh that year.

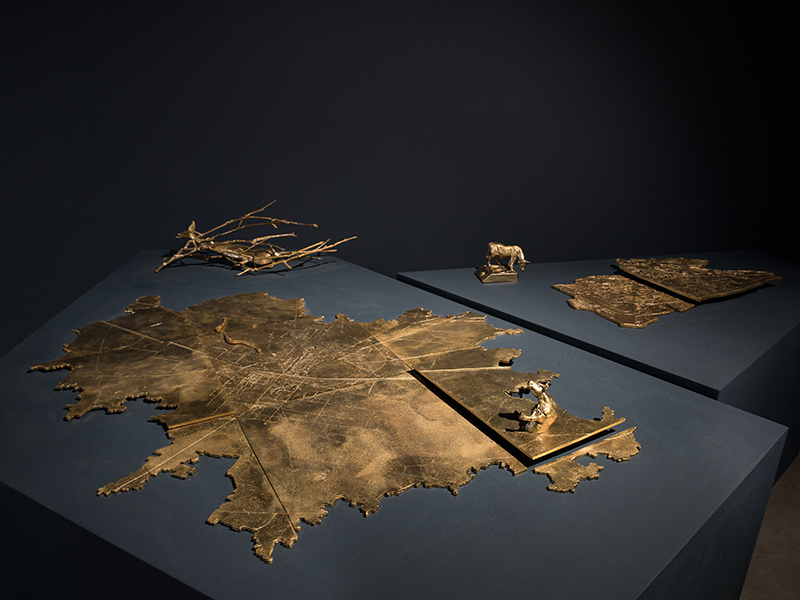

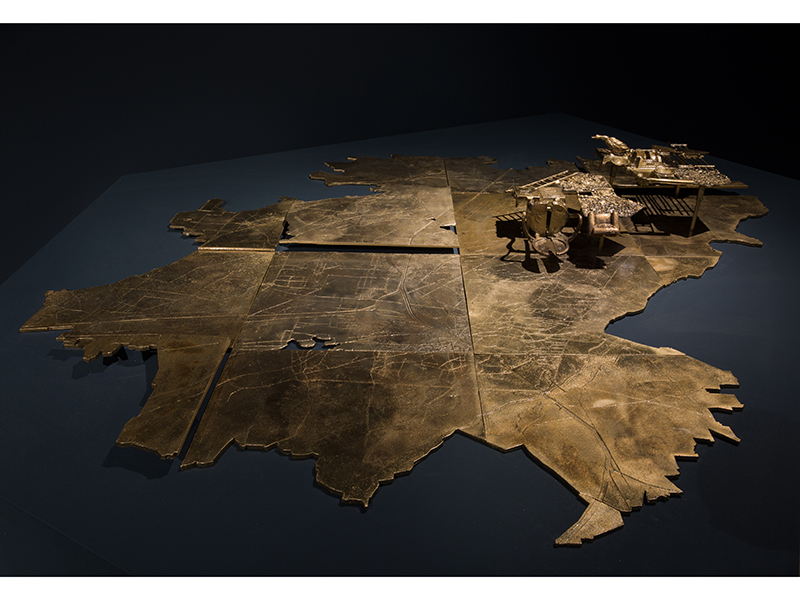

In this work, the contents of the document become a voice-over that acts as a narrative backdrop for the sculptural works. The sculptures are, essentially, maps of 11 of the cities of which the document speaks. Placed on deep gray geometric volumes, the maps are exciting objects to behold. At once belonging to the earth and hovering above it, matter of fact and emotional, they vibrate with the energy of the coastlines they represent. I found myself at once drawn to the material sensibility of these sculptures.

Naiza Khan is an artist who seems acutely aware that the making and materiality of an artwork can often hold just as much meaning as the end result. The sculptural components of Hundreds of Birds Killed are no exception, bringing together modern and artisanal methods of making. The maps were laser-cut in Plexiglas in London and later cast into brass by artisans in Golimar, a neighborhood of Karachi that once housed a shooting range for the British colonial army (goli means bullet,” and mar means “fire” in Urdu); it is now famous for brass handicrafts. Through such decisions, the processes by which Khan chooses to bring her work to life create a resonance and a delightful friction between past and present. A close look at the sculptures reveals accumulations and pockets in which toy airplanes, bird feathers, and scraps of wooden scaffolding and driftwood seem frozen in the act of being washed up on a beach. As translated into the sculptures’ homogenous medium of brass, these objects are ossified and one with the maps that they garnish, creating a sense of lived history that is inseparable from the land. And just as the land cannot be separated from its history, the sculptures cannot be separated from the conditions through which they were produced.

I have never been to Golimar, but I imagine it’s not so different from similar neighborhoods in Lahore, where I live—tight alleyways populated by craftspeople and the paraphernalia of their particular craft. Such places in Pakistan’s cities are true microcosms of creation and commerce working in tandem. Generally, the workshops in these bazaars are not independent of one another, but rather interdependent, relying on a guild-like system where each kaarkhana (small factory) specializes in a particular step of an elaborate making process. Khan and other contemporary artists who negotiate such spaces must ask themselves the inevitable question: what is their role in this complex ecosystem? During our conversation in early 2020, the artist had much to say about the role of gender and class in her interactions with the artisans of Golimar:

That’s an interesting relationship because the artisans in Golimar are all men. It’s a really interesting space, much more interesting than my work, I think! I’ve been thinking more and more about these works which are shown in galleries and museums, and the milieu out of which they’re produced, and how these people relate to the work. What my position is within that community, my relationship with the person who’s working to help me fabricate [this work]. It is infinitely interesting and problematic and it doesn’t exist outside of the work. It’s part of the conditions through which the work evolves and is revealed. That’s a whole conversation, that interaction of going outside the privileged space of the studio, into the market, into the space of making and producing. It’s very congested and it’s a completely different set of circumstances. And the question is, how do those circumstances inform the work? Like if I’m working in Golimar, in these small gallis in North Karachi, the speed with which I have to work is much faster than how I would work in my own home. And [the locals] might feel awkward, wondering why I’m sitting there day after day. How do you negotiate that discomfort with a male workforce, being a woman? How do you negotiate issues of class? How do you negotiate being a “madam” in their eyes? You can’t dismiss these questions; you have to negotiate them. These processes don’t talk to each other unless you’re taking into account how they feel about it, what you learn from them, how much say do they have in what is made and how it’s made, what are the technical hurdles and possibilities. I feel very conscious of those questions and I think that I learn a lot from them.[1]

In Khan’s experiences of navigating male-dominated urban spaces as a privileged woman and an artist, I find resonance with my own forays into similar spaces. There are many questions to be asked through these interactions, and no easy answers to be had. Of course, these questions of gender, class, and the roles assigned to women are by no means new, though they have gained some popular visibility across the globe in recent years. Khan herself addressed them more than a decade ago in a solo show in London through her body of work, The Skin She Wears, which consisted of a series of large drawings as well as a number of steel armor suits.

Of her countless trips over the years to both the heart and the margins of Karachi, she says, “sometimes I feel like the work is an excuse to make an intervention with the body…” This notion of an intervening body is interesting because it speaks to a perceived otherhood a body might take on in certain spaces, while also hinting at the strength to be found through such interventions. It seems to me that this idea is at the heart of the works in The Skin She Wears, not just the armor suits, but the drawings as well. Working with a model to create her many large drawings, Khan found herself wrestling with the difficulties posed by depictions of nudity in art at that time in Pakistan.

Drawing the body within the context of living in Karachi was a very different experience [from] working at art college in England, because of the [shift in] environment, space, politics, and cultural issues around working with the female nude. The importance of shifting that locus of ideas onto attire was important to my understanding of how this image might be communicated without the baggage or the prejudice of “nudity” or the “nude body,” which, I realized, had kind of shut down in people’s perceptions.[2]

In this way, a necessary act of self-censorship opened up an array of symbols and meanings that, in time, became perhaps more powerful and charged than a straightforward depiction of the nude female body. The attire found in Khan’s drawings ranges from lingerie to bulletproof vests. Holding up the garments is the body of a model who, herself, is absent. The contours of her body turn clothing to shell, drawing attention to the second skin nature of attire. With these drawings calling out to be objects began the development of the steel armor suits, as well as the artist’s long engagement with various metals. Though at a glance the work is conceptually driven, it is clear that the material properties of metal were very much a guiding factor. The armor suits were constructed from pieces of sheet metal cut to the patterns of actual lingerie, then fashioned into the contours those garments would ostensibly cling to when worn.

Other works in this series imitate the playful falls of flowy skirts, not static, but expressing movement, as a skirt worn by a body would. And so, in the absence of a literal body, frozen by the material constraints of metal, these impossible garments come alive with a set of implied actions. The suits are built around skeletal frames, which are quite beautiful in themselves, and then covered with pieces of sheet metal that are raised, curved, and folded to mimic the garments. The use of sheet metal, and the subsequent hollowness of the armor suits is, in my eyes, integral to the works. There is space to be filled with interpretation, as well as a certain sense of wary intimacy, at once inviting and withdrawn, in being able to peer inside the hollow garments. A few of the armor suits conceal chastity belts inside them, which I can only imagine add to the unease of the individual peering inside.

Unlike the brass sculptures from Manora Field Notes, the armor suits are not homogenous in terms of material. The galvanized steel is accented by several other materials. Of particular note is the piece titled Armour Suit for Rani of Jhansi, which invites us to imagine a historic figure (one famed for being a warrior queen) through the work, while encouraging a more nuanced perception of such a figure through the juxtaposition of steel with feathers and leather. As the novelist Kamila Shamsie observes, the armor suits constantly allude to certain mythologized versions of femininity—Rani of Jhansi, Joan of Arc, the Valkyries, the Amazons—and then go on to subvert those narratives with the inclusion of lacy, silky, feathery detailing, in addition to the lingerie-inspired forms themselves.[3]

The welded construction of the armor, seams studded at short intervals, gives the suits a “jewel-like”[4] appearance while simultaneously referring back to the hands of their maker. The welding marks come not from Khan’s own hands, but the hands of the man, a welder by profession, who assisted her in the fabrication process. Here, I struggled to reconcile the incongruous image of these feminine forms lying sideways in the masculine spaces, such as Golimar, where the work is done. The unease I feel through this image is similar to the irrational bashfulness one might feel when seeing a “naked” mannequin in a very public setting (a fairly common sight in many a crowded bazaar in Pakistan). It is also through this image that I begin to fully grasp the multilayered nature of the act of “making an intervention with the body.” I would argue that the sense of unease I feel is intentionally cultivated by the artist, and it is rooted not in the works but in the very spaces, emotions, conversations, and interactions from which the works emerged. The intervening body is mutable and contested, belonging at once to the works, the artist, and the men whose skilled hands Khan appropriates to create the works.

Another of Khan’s works warrants mention here: the installation The Crossing, 2008. A wooden boat floats in a small lagoon in the Pakistan Pavilion at Art Dubai, 2008, manned by several of Khan’s feminized suits of armor. Two of the armor suits “stand” upright in the boat. Others lie sideways, while others still are skeletal frames. The variation in form and posture among the suits adds a sense of theater, and we are left wondering at the roles of these characters. Where are they going and why? The title itself, The Crossing, hints at the temporality of this silent performance. Bringing the suits out of the privileged gallery setting and placing them in a more precarious position at once activates them and opens up new points of interpretation. I am reminded of the Manora Field Notes sculptures, particularly the fossilized objects, remnants of lives lived, being washed ashore. The Crossing seems to me a conceptual predecessor to that idea, so similar in language and texture. In this work, I also find echoes of Khan’s accounts of taking boat rides to cross Karachi’s harbor and go to Manora island, to make interventions that have transformed into several rich bodies of work. The motif of the boat appears frequently in the artist’s work, both in her watercolors and many of her sculptures. The boat is at once object and space. I imagine crowded ferries crammed with people from every walk of life, the spaces as gendered as those of Golimar, undulating with possibility. In understanding the set of conditions that the work stems from, the layers of meaning to be found in The Crossing begin to unfold.

The boat motif appears again in the four-channel video installation Sticky Rice and Other Stories, this time in the form of ornate miniature boats that are sold as souvenirs to visitors on Manora island, as well as actual locally made kashti (boats) that are used by locals and visitors to traverse the waters. The video installation contains footage of the artist’s various interactions with the island spread out over a decade, a record of her efforts to delve into the visual and vernacular culture of the place. In one clip, the artisans engaged in building boats talk to the camera. With the inclusion of this clip, Khan has brought us back to the essence of the symbol: before it is a vessel for transport, it is an object crafted by skilled hands. Whether it is in the studio, in the bazaar, or in a workshop producing a kashti that will go on to adorn the island landscape, the spirit of making and crafting, with all its nuance and baggage, is ever-present in Khan’s creative practices. Craft and making are not relegated to one-dimensional physical processes, but extend to the conversations and interactions through which ideas have developed over the course of this artist’s long career. There is much to learn within Khan’s oeuvre about the various dimensions of making, of which I have only begun to scratch the surface.

[1] Naiza Khan in discussion with the author on May 7, 2020.

[2] Naiza Khan in discussion with the author on May 7, 2020.

[3] Kamila Shamsie, “The Dreams Descend,” in The Skin She Wears, Naiza H. Khan, eds. Anna Marie Rossi and Fabio Rossi (September 2008), 7, accessed on March, 15, 2020, http://rossirossi.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Naiza-Khan-The-Skin-She-Wears.

[4] Naiza Khan, quoted by Iftikhar Dadi, “Allegories of Encounter,” in The Skin She Wears, Naiza H. Khan, eds. Anna Marie Rossi and Fabio Rossi (September 2008), 12.