It is with immense sadness for her death and abundant gratitude for her life that I write this appreciation for Janice “Jan” Yager. Her death, after 12 years with breast cancer, will not extinguish the importance and quality of her jewelry. It will not diminish her meaningful advocacy for the field of jewelry. Her work will live forward, and loving memories of her as a person of remarkable artistic merit and character will continue to inspire and enrich many of us who knew her and her work.

Jan and I met in 1990, the year she decided to take a sabbatical to further her artistic growth for potential new work. To begin this adventure, she decided to spend time learning more about the history of jewelry.

I had been teaching Craft History and Contemporary Craft when we both arrived separately from Philadelphia to attend the “History of Twentieth Century Craft Symposium” at the American Craft Museum in New York. On a break between lectures I overheard a woman pushing the point about how jewelry was not getting the representation it deserved at the symposium. Startled to hear her accurate portrayal, with which I agreed, I stepped forward to meet her. It was Jan, whose work I had previously known. That memorable meeting personified Jan at her best—articulate, informed, forthright, and passionate about jewelry. Throughout her life she advocated for jewelry through oral histories, lectures, articles, and conversations.

Jan and I shared an interest in Craft, a field with a valuable history, an explosion of amazing contemporary works, and significance as Art. Our friendship blossomed most fully, though, through our shared experiences as craft artists working in the studio building at 915 Spring Garden Street, Philadelphia. Jan came in 1983, and I arrived in 1990. After moving into the building of about 90 artists on five floors, I learned with delight that Jan’s studio was just doors away from mine. We worked there until 2015, at which time the building suddenly and traumatically shut down for code violations after a small electrical fire.

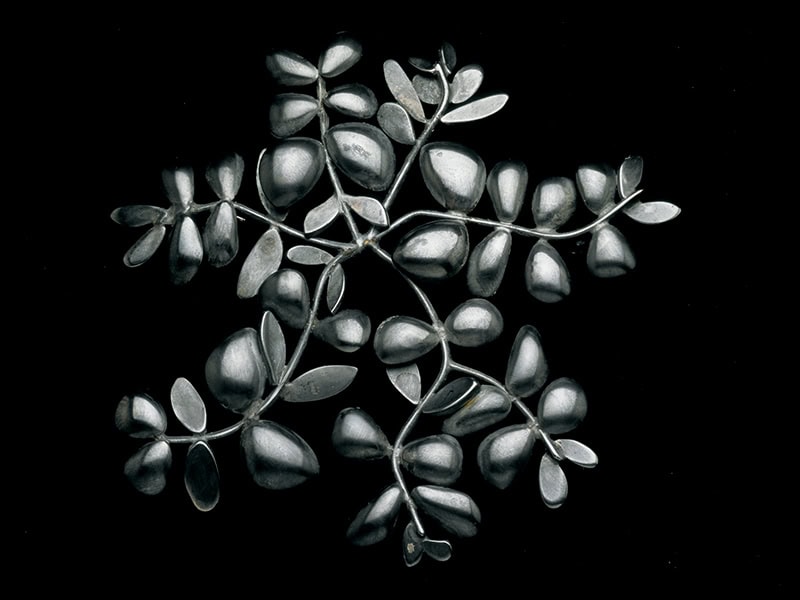

Jan and I had been educated in art schools with excellent programs based on traditional craft materials—metals for Jan and clay for me. As craft artists pursuing professional careers, we shared some common hurdles. There were the difficulties of being female artists in a fine art culture, often male-centric, resistant to the value of crafts. There could be prejudices against particular aesthetics and philosophies among some makers within craft and some buyers newly discovering the vibrancy of the field. Jan’s necklaces, with their smooth beach stones and urban textures, certainly disrupted a jewelry tradition that valued precious gold and gems to adorn women and elevate their status. Jan once remarked about the difficulty of dismantling a barrier of acceptance for her work given the cultural insistence on a string of pearls! There was also the pragmatic fact that industry could produce copious products efficiently and cost-effectively with the materials we used, too. With these realities, our shared desires and efforts to make personal works of quality on a small scale helped anchor the friendship.

Because Jan’s jewelry has been documented so well, I will keep my comments general instead of discussing individual pieces. Firstly, I want to affirm how much I admired her success in making a living through her extraordinary work. She had the business acumen to make her efforts profitable enough to generate new pieces on her artistic terms. Many craft artists teach in part to have economic security, time, and freedom for their work. But Jan did not want to teach, and she did not compromise her values for producing creative, beautiful, and challenging work in the process.

She told me she had come to Philadelphia primarily because the city had already developed a market with a fairly educated audience for crafts. The Philadelphia Craft Show under the patronage of the Philadelphia Museum of Art had certainly helped in that regard. Philadelphia also provided affordable living and studio space with easy access to New York, Baltimore, and Washington, DC, markets.

Jan predominantly valued aesthetics, but she worked out a way to combine industrial techniques along with hand skills to make singular pieces efficiently and cost-effectively. Several factors fostered her dual interests in industrial practices and business prowess. One was growing up in Detroit, at a time when automobile production had significant vitality, and her family owned a small business. An additional influence was attending the Rhode Island School of Design in Providence, a center of jewelry manufacturing. For a Jack Prip assignment that required her to incorporate a manufacturing process into a piece, she visited jewelry and metals companies in Providence.[1] Another teacher, Ken Hunnibell, “opened our eyes to bridgeports and metal lathes, the drop hammer, and hydraulic press.”[2] As I recall, she also appreciated her “business practices” course with Dale Chihuly.

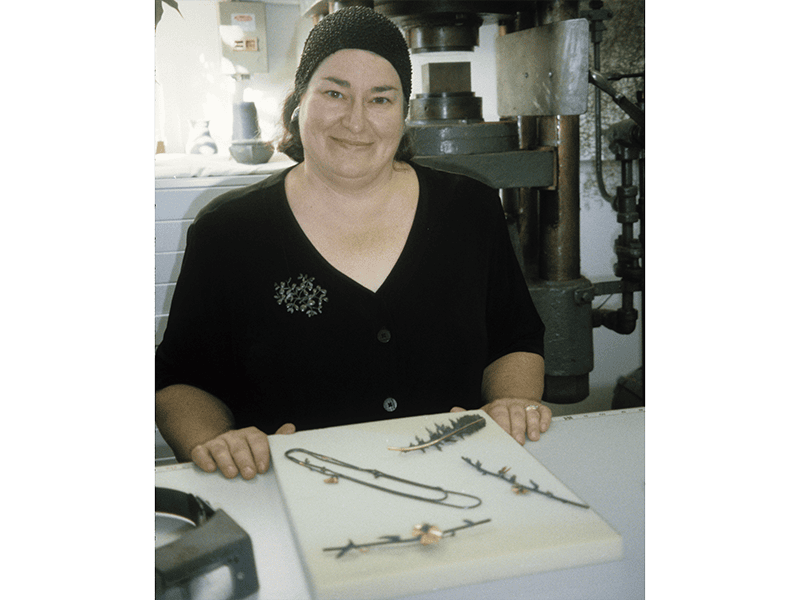

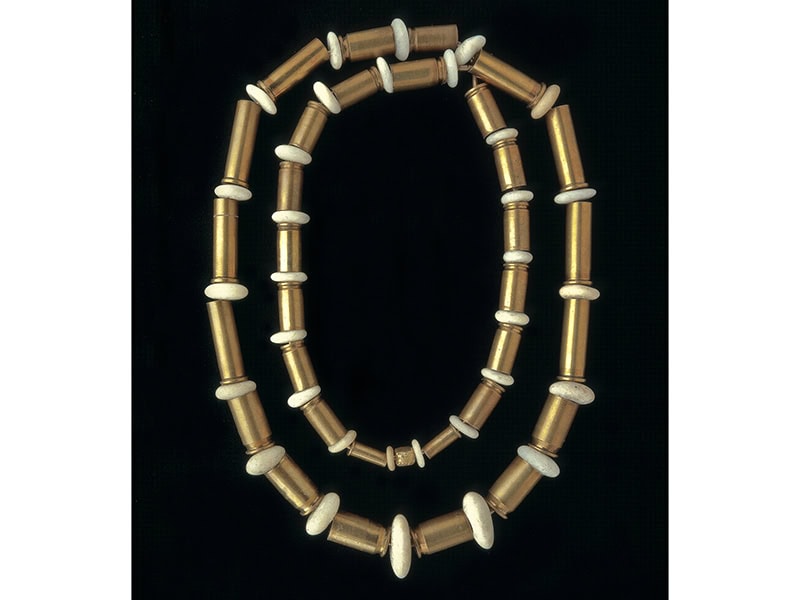

In her “915” studio, industrially based equipment helped her make special chain, stamp out patterns such as tire tracks, and puff out flat pieces that she put together by hand with artistic consideration. Earrings had different surface patterns she could duplicate easily, and puffed metal forms and drilled stones could easily slide on a chain with configurations unique to each necklace. She credited Paul Mergen, her undergraduate teacher at Western Michigan University, in Kalamazoo, with her desire to prioritize “personal touch” over process.[3] That might mean swelling the volume and coaxing the curvature of her geometric forms to encourage some softness and grace over metallic rigidity. Around the time of her daughter’s birth, she constructed tiny “puffy” gold heart necklaces to celebrate the joy of young daughters. Most importantly overall, she made visually strong jewelry with utmost skill that functioned well on the body, that evoked pleasure when looking at it, and that reflected her personal viewpoint.

“In Detroit, in Kalamazoo, in Providence, and now in Philadelphia,” she said, “my goal has always been to simply bring my ideas to fruition. For me it’s always been how can I be an artist first, a business person a necessary second. Fortunately, I never believed it was an impossible task.”[4]

It is my understanding that her trailblazing approach, especially in the use of the hydraulic press, influenced other jewelers in the work they created. With time Jan expressed a desire to leave those puffed forms behind her. She had generated enough savings to afford her sabbatical to study jewelry history (and anything else that appealed to her.) She would concentrate fully on making a singular piece or series of pieces with an entirely fresh approach.

Just as Jan had garnered earlier inspiration from picking up stones on an ocean beach for use in her necklaces, she began “beachcombing” the environment outside our studio building for inspiration.[5] “915” had initially held the offices of the Reading (Railroad) Company, and overgrown tracks lined the back of the building. A firing range faced the front door across the street and enthusiasts could buy a gun around the corner. Gunshots from the range were audible as we worked. A field with weeds and litter grew in the adjacent city block. For safety, we all moved our cars closer to the building’s front door after 5 p.m. Jan had fortified her studio door with steel for protection and worked hard, long hours, often into the late evening. The environment around the building, with its crack vials, bullet casings, cigarette butts, syringe parts, and weeds, would prove to be fertile ground for her new work.

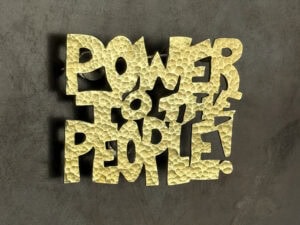

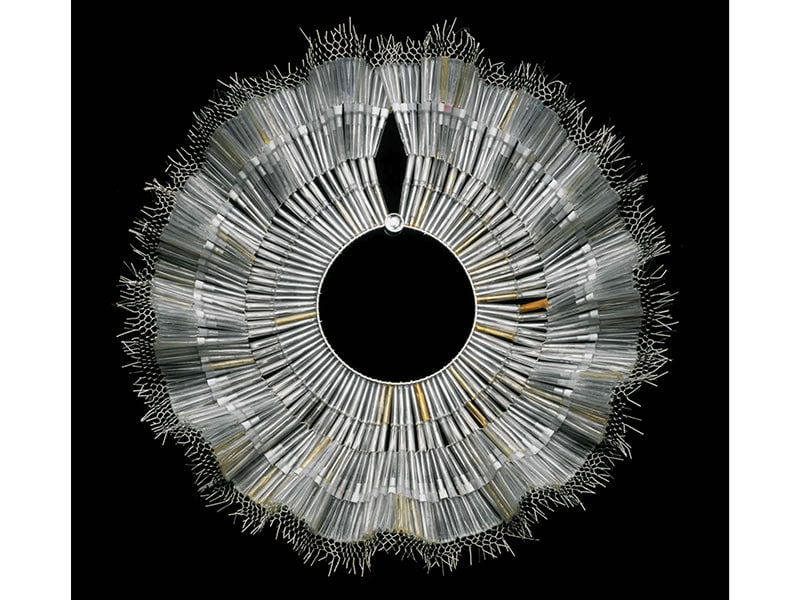

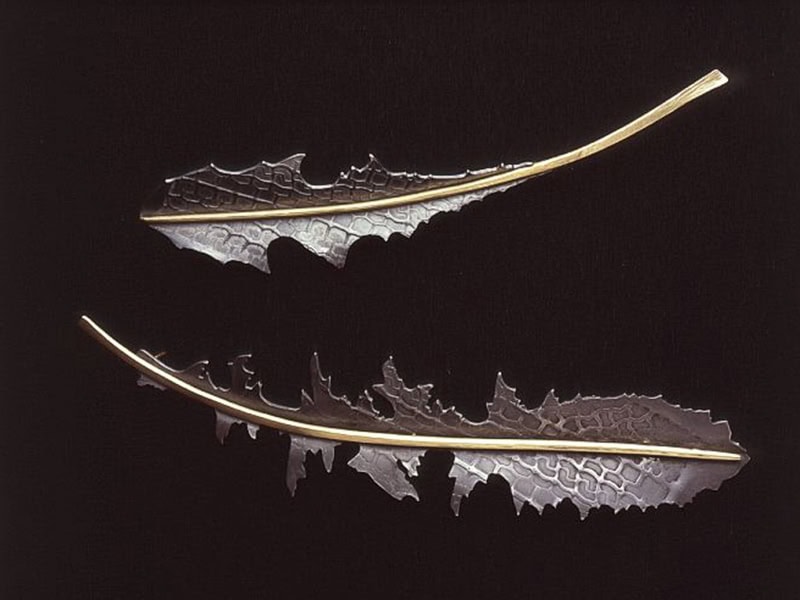

Her exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum, in 2001, was a culmination of work she had produced as a result of her sabbatical. Generally, the work of this period used the detritus from the neighborhood to re-create jewelry forms already designed in the past by people from various heritages. Examples include a Maasai collar, a Victorian guard chain, and a Lenni Lenape wampum belt. The form of a ruff or a necklace referenced the history of jewelry, but her materials, such as bullet casings or crack vials, confronted contemporary concerns of addiction, poverty, or violence in American backyards and distant countries. When looking at her work, layers of associative ideas can easily multiply. A small crack vial cap cast in gold encourages thoughts about the material’s privileged associations for those who can afford the metal, as well as with those who control the mines, produce it, sell it, and/or trade it. The intriguing beauty of one of her pieces can easily coexist with charged reactions to its materials, and even to musings of unsavory practices by corporations, cartels, or individuals.

Fabricated weeds in a regal tiara also make us confront paradoxical complexities with such concepts as “invasive weeds” and “global warming.” Again Jan’s ability to integrate the components of her pieces into an aesthetic whole, along with the charged associations of her materials, and the reference to historical jewelry forms, evoke a multilayered dissertation on Art and Society.

The building where Jan worked so diligently helped facilitate a multitude of permanent and enriching friendships through spontaneous lunches and studio breaks. The photographer Jack Ramsdale photographed her work for years, and the designer and sculptor Steve Tucker produced an amazing setting for her solo show at the Victoria and Albert Museum. Jan willingly shared practical and artistic experiences of value to others, such as suggestions for grants and professional contacts, tips for display, or enthusiasm over particular pieces another had made. Her wealth of knowledge surfaced naturally, generously, and always for the benefit of another. She wanted other artists to succeed!

Back in 1990, Jan had written, “I chose to create jewelry because I am drawn to its intimate scale and to its power as repository of both meaning and sentiment. Metal offers a wonderful tactile format in which to explore ideas with form, volume and surface. In my work the contemporary and the ancient, the natural and the made, reality and illusion, are placed in counterpoint. … Hopefully, my work will become even more refined, time-intensive, and thought-provoking.”[6] Yes, Jan, indeed you succeeded, and your work in numerous museums, private collections, and personally worn by so many admirers attests to a continuum of accomplishment.

Since Jan has died, I have often visualized the vitrine that enclosed my vase and her necklace at the 1990 Philadelphia Museum of Art juried exhibition of area artists. I believe our work embodied the essence of each of us, and that image of “being together” in the vitrine, even before we met, now memorializes our friendship—a friendship introduced through serendipity and nourished over time with common interests in craft history and contemporary craft, with delight in having studios near one another, with mutual admiration as makers, and with shared joys and sorrowful losses of loved ones.

The loss of Jan is harsh. She dearly loved her husband, her daughter and recent son-in-law, and her wider family and friends, who also loved her. I especially miss her humanity. Her calm comportment felt comfortable and close. She extended compassion to many and helped out some financially. Honesty, creativity, practicality, and perseverance infused her life. She worked hard with skill and thought, and yet laughed heartily at life’s absurdities and surprised us with her wise quips.

I will always celebrate Jan’s exceptional jewelry and her remarkable contributions to the arts. I will forever cherish her abundant goodness! And to keep her close, I have tucked her into my heart, now softly “puffed” with her enduring essence.

[1] Jan Yager, “Providence: An Incredible Resource…,” opening speech, Society of North American Goldsmiths Conference, Providence, RI, June 18, 1992. ©Jan Yager.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Jan Yager, “Artist Statement,” December 8, 1998. ©Jan Yager.

[6] “Portfolio No 73: Jan Yager,” Craft Arts International Magazine, Sydney Australia, No.18 (1990): 88.

We welcome your comments on our publishing, and will publish letters that engage with our articles in a thoughtful and polite manner. Please submit letters to the editor electronically; do so here.

© 2024 Art Jewelry Forum. All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. For reprint permission, contact info (at) artjewelryforum (dot) org