Stein in hand, I surveyed the beer hall on the Saturday night of 2025’s Munich Jewellery Week. The place was packed, mainly with tourists. Among them, though, was jewelry icon Karl Fritsch, and the many Maori and Kiwi visitors who flew in this year, dancing and singing to the blissful, accordion stylings of resident performer “SüdtiRoland.” My friends and I squeezed into another group’s table, and introductions were made. I believe the three women opposite us were adult students at KunstModeDesign Herbststrasse, in Vienna, Austria, which specializes in art, fashion, and jewelry design. This may have been their first time in Munich.

Stein in hand, I surveyed the beer hall on the Saturday night of 2025’s Munich Jewellery Week. The place was packed, mainly with tourists. Among them, though, was jewelry icon Karl Fritsch, and the many Maori and Kiwi visitors who flew in this year, dancing and singing to the blissful, accordion stylings of resident performer “SüdtiRoland.” My friends and I squeezed into another group’s table, and introductions were made. I believe the three women opposite us were adult students at KunstModeDesign Herbststrasse, in Vienna, Austria, which specializes in art, fashion, and jewelry design. This may have been their first time in Munich.

If one were to judge the art jewelry scene based on this week alone, one might make the following assumptions: There’s a widespread global community, collectors, exhibition opportunities, cultural and social interest for our field and what we make, and, after school, the possibility of a successful career. It all appears very viable. But—“how does one actually make money?” one of these women eventually asked.

I was sitting between the two founders of Current Obsession, who, to oversimplify, have been trying to “make art jewelry cool again” since 2013. We were both the best and maybe the worst people to answer. My response? “You don’t.”

Years ago, I, too, was perplexed as to why the field’s collector base didn’t ever seem to expand to a wider, younger audience. As a curator, fine jeweler, and someone who has studied, researched, written about, and worked with scores of art jewelers over the last 13 years, I now have a lot of thoughts.

For one, the market that appears to exist when wearing Munich’s rose-colored glasses is simply not there. And I can skip listing all the international gallery closures within the last 10 years, can’t I? Together we talked about different definitions of success in the field, and various ways makers can navigate the fewer commercial and rarer institutional opportunities available to emerging talent. As Munich shows, don’t wait around for anyone: embrace collaboration and create the context for your work as though it’s part of your practice.

There was more, but here I’ll refrain from a ranty meander. I can’t solve contemporary jewelry’s problems, but I can offer its most viable path beyond the confines of MJW and other isolated art jewelry spaces. It’s metal. The relevance of our field is metal, it’s terribly simple. Look at our dancing friend Karl, one of the very few contemporary jewelers with widespread name recognition. It’s in his straightforward but masterfully playful subversion of recognizable archetypes in jewelry—common, traditional, everyday forms—but more importantly, the use of the enduring: silver and gold. Let’s be honest, the gemstones help, too.

The partiality to plastics, resins, silicone, and other “unconventional” materials in art jewelry of the 1980s, 90s, and early 2000s still reverberates in emerging work, but I think those days are largely over, even despite historically high metal prices. The conceptual language of the field has also changed since then, as younger makers are turning away from overtly narrative or figurative series with big sculptural pieces, instead favoring more wearable jewelry with contemporary tropes, references, and forms found in pop culture. Like Karl, more and more who work this way are not bogged down with justifications for why they make what they make. Sure, the work can be about something, but it can also just be.

Those who I believe have this in common, who make work you can place anywhere, include, in no particular order: Noon Passama, Georgina Treviño, Moniek Schrijer, Aaron Patrick Decker, Göran Kling, Helen Britton, Kalkidan Hoex, Hansel Tai, Annika Pettersson, Adam Grinovich, Lola Brooks, Sophie Hanagarth, and Everett Hoffman. There are others who came before them, too. Think Lucy Sarneel. Giampaolo Babetto. Art Smith. All their work has a certain resonance hard to describe, a coolness versus trendiness, a nonchalance, never overeager. Of course there are others.

Metal is jewelry’s greatest common association. It is self-rationalizing. The Elemental Return implies a homecoming to the realm of, well, jewelry. “How does one actually make money?” By acknowledging this fact. I described my 70/30 theory to the students: Every jewelry piece should at least be 70% metal, 30% something else. And if the subset happens to be another sincere, recognizable material (clay, textile, etc.) or, better yet, gems or something gem-adjacent, the higher the likelihood the work will have legs no matter where you find it. It doesn’t have to be all precious, either. Metals or alloys like aluminum or iron, tin, or steel can count toward the ratio. This is just my opinion, and my idea of a formula to make art jewelry less of an object in a drawer, an inside joke, an oddity. Metal is covetable by all. And normalize using the word “client” over “collector,” I suggested.

In the shows I found most excellent in Munich this year, various metallic elements took center stage. The presentation of students, alumni, and faculty from the jewelry design BA program at Central Saint Martins is always reliably good. This year it was entitled Cycles. Standout pieces included Dominik Cunningham’s The Four Phases of the Sun, which illustrated personal iterations of ancient African symbols and philosophies in cast aluminum. Necklaces by Giles Last and Lili Murphy-Johnson riffed on taken-for-granted clasps and closures. I also found the puffy silver rings by Elea Troiana enticing. They explored intimacy and the concept of home by tucking gems away inside the bands. Thanks to past and current lecturers Caroline Broadhead, Lin Cheung, Max Warren, and Lucie Gledhill (who all extraordinarily embrace the forms and material foundations of jewelry in different ways), graduating work similarly remains extremely jewelry-nuanced and readable as such.

Let There Be Light, at Kunstarkaden Muenchen, featured work by Marion Blume, Nora Reitelshöfer, and Florian Clemens Meier, all now exiting Munich’s Akademie der Bildenden Künste, and all metal devotees. Blume’s chunky pair of rings made of bismuth—a heavy, brittle, but alluring metal I don’t think I’ve seen in art jewelry—were a highlight. They seemed to be cast from the same pour and then snapped in two. Meier’s melty, classic oval signet rings in gold were also bold choices given the context of Munich Jewellery Week.

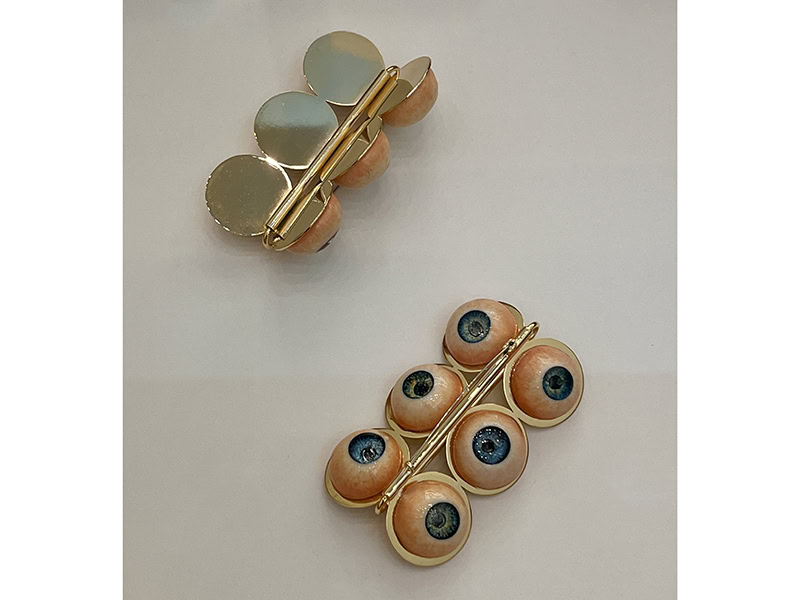

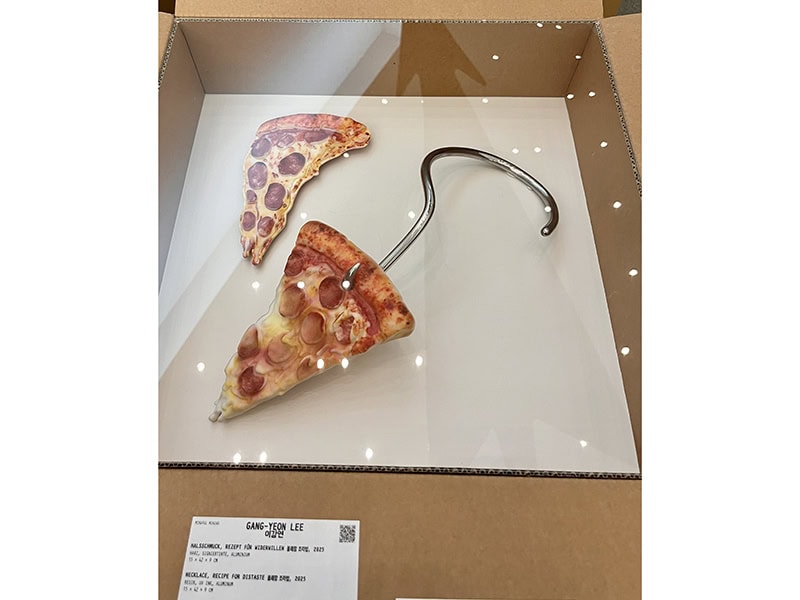

Even the maximalist work at Mindful Mining, in the Pinakothek der Moderne, almost always endorsed metal with crucial, formalizing elements. The exhibition featured work from the department of metalwork and jewelry at Kookmin University, in Seoul. Gyuri Kim’s Peep brooches are a great example; the gold-plated brass structure behind the six photorealistic eyeballs made from polymer clay, paint, and resin is actually the front of the brooch, not the back. And Gang-Yeon Lee’s giant necklace of a pizza slice wouldn’t be nearly as jarring without the large metal hook that wraps around the neck and pierces right through the pendant.

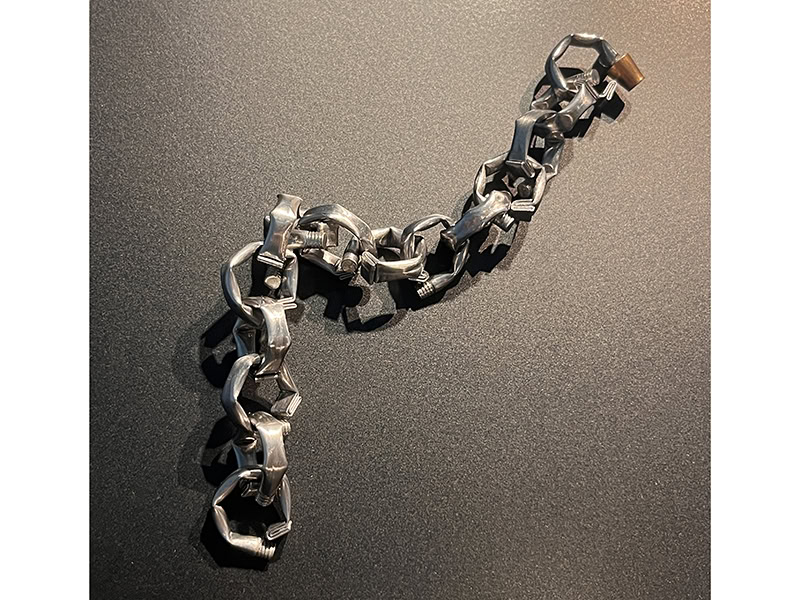

Minseok Kim’s industrial insects of stainless steel and nickel silver were also of note, as were Soo-Young Kim’s abstracted geometrical brooch Purple Flavor, which combined PLA and acrylic lacquer with mirror-finish sterling silver and platinum plated brass.

Silver shined in the group exhibition Pin Pin An An—Reimagining Amulets, which explored the concept of “safe and sound” through the perspectives of Taiwanese artists An-Chi Wang, I Ting Wang, Yu Chun Chen, and Amal Yung Huei Chao. Each of them revisited various amuletic tropes in their culture, imagined via personal experiences. For example, Yu Chun’s gorgeous, hand-fabricated silver whistles, Guardian Beep, recall the protective role the accessory played around her neck as a child, a succinct and sensitive reimagining that appeals to the intergenerational memories of people from all over.

I Ting uses the symbolism and shapes found in Guangming lanterns to determine the forms of her Votive pendants, which are made of silver or enameled copper and simply strung on thin cord. The chased and repousséd silver pendants by An-Chi are meticulous, lovely, and at times even humorous, decorated with fruit and/or phrases like “Doubly Lucky”; all are personal reinterpretations of wish-carrying totems with a distinguished touch. The combination of material choice and subject matter make all of the jewelry in this show wonderfully grounded in the cardinal rationales, superstitions, or traditions of amulet-carrying. The work justifies itself.

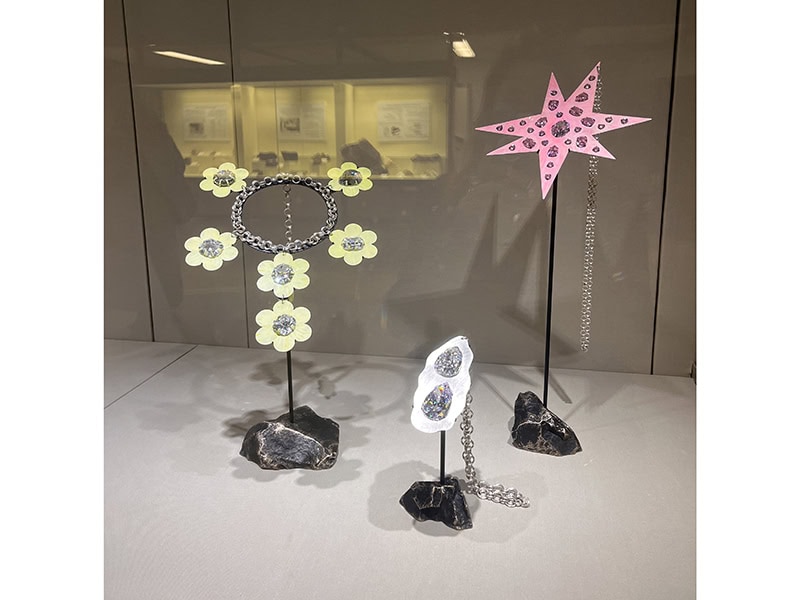

Moniek Schrijer, who presented her solo show, Hologram of a Diamond, at the Mineralogy Museum Munich, is one of the best examples of someone who renders plain old sheet metal cool, without having to transform it entirely. Zesty shapes, colorful paint, and giant gemstones remix ordinary jewelry conventions into fabulous pendants and chainlinked neckpieces, bonkers yet still accessible to the passerby. There’s a fun overlapping of real and fake at play in her work, which was heightened by the show’s venue. It was the perfect pairing and context from which to really see, understand, and get excited about her jewelry, regardless of the day, week, or audience.

I found metal all over Munich this year. I use the word “salient” to describe it because might it in a way be courageous to put it in the epicenter of art jewelry? For 20-odd years, Schmuck and MJW has been the place to take the global temperature on tendencies and approaches being embraced and left behind. The origin story of our field revolves around the relinquishment of metal in favor of conceptual value and material exploration, so as to distance itself from fine or luxury jewelry and fashion. Makers have been encouraged to create their work out of anything and everything else. And for a long while, we have done that. But I believe metal should be resonant once again. Working with it, in transparent ways, like the artists mentioned here do, means resting on a time-honored substance, knowing people will more easily understand and value it, and pay for it, and hopefully pass it along. It is undeniable.

And using metal gets us out of our heads. We no longer exhaust ourselves by trying to convince the world our ideas have more value than the material we make the work with. And it’s OK. Our jewelry does not have to abandon itself any longer if we don’t want it to.

A long time ago I wrote a text comparing art jewelry to Relational Aesthetics—the practice theory popular in the early 2000s which prioritized art as experience over objecthood. That’s so silly and pretentious. My, how my script has flipped.

These opinions expressed here are the author’s alone, and do not necessarily express those of AJF.

We welcome your comments on our publishing, and will publish letters that engage with our articles in a thoughtful and polite manner. Please submit letters to the editor electronically; do so here. The page on which we publish Letters to the Editor is here.

© 2025 Art Jewelry Forum. All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. For reprint permission, contact info (at) artjewelryforum (dot) org