As part of his review of the Legnica Jewellery Festival, Stephen Bottomley reported on a lecture by Mah Rana, which in his account did not provide a satisfactory assessment of the focus of her lecture on her Meanings and Attachment project. In response, Ms. Rana wrote a letter to the editor, in which she seeks to address Bottomley’s criticism and outlines the conceptual premises of her research. Given how influential this project has been for a generation of makers, we thought it would be useful to reproduce her letter here in its entirety.

—Benjamin Lignel

I was curious to read Lost in Legnica, Stephen Bottomley’s review of this year’s Silver Festival in the aforementioned town, especially because I was told that he had written in some detail about We Are Our Stories, the lecture that I presented at the festival’s symposium, Boundaries of Global Art: Classic in Post-Modern Reality.

Sure, as Stephen described, the introduction of my talk included statistics such as the number of people who have taken part in Meanings and Attachments. But if he was “interested to hear some conclusions or critical reflective analysis,” I would invite him to revisit the key aspect of my presentation, which asked, “Do we use jewelry as transitional objects?”

This is a theme that I had previously written about in “I never take it off” (2006), a short essay for a Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art publication. So with references to Marcia Pointon’s essay “Surrounded with Brilliants” and Winnicott’s object-relation theory to underpin my observations from talking with so many people about the jewelry they wear and why they wear it, my aim was to highlight the interplay of psychological and social factors that determine and shape our emotional attachments with jewelry.

“I never take it off” is a phrase I often hear from people describing the jewelry that they are wearing. So for me, this recurring proclamation has continued to reinforce the idea of jewelry as a transitional object, a term defined by Winnicott to represent any material object “to which an infant attributes a special value and significance and by means of which the infant is able to make the necessary shift to see itself as being separate and independent to its mother.”

Many of us have strong connections to the jewelry that we wear. But those connections can also apply to pieces that we own but choose not to wear. I certainly have pieces that are very important to me and would be nervous of wearing in public for fear of losing them.

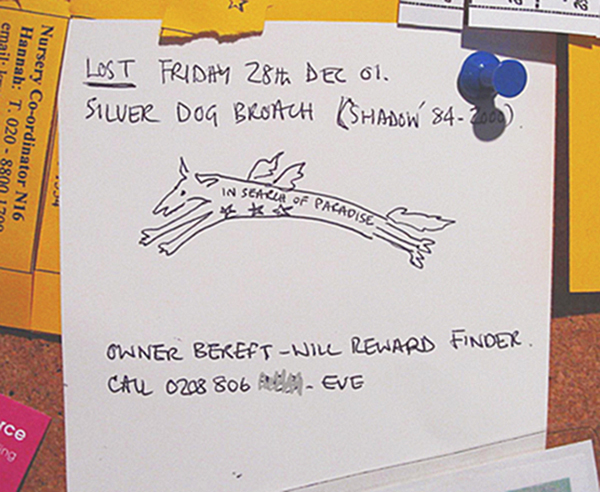

Because if I did lose them, I’m sure that I would feel exactly the same way as this person did who pinned this note in a Whole Foods Market store. And perhaps the fear of loss that we see expressed in this note is a residue of the separation anxiety that we faced as infants, holding close our transitional object to protect us from loss.

In her 2001 essay “Surrounded with Brilliants,” Marcia Pointon writes about how gifts “not only represent people, they also stand in their stead,” and to focus her argument she quotes Marcel Mauss: “to make a gift of something is to make a present of some part of oneself.”

Perhaps, in certain situations, when we receive a piece of jewelry from someone, we consciously or unconsciously acknowledge that they are giving, as Mauss describes it, some part of themselves. And we have learned that social custom expects us to take the ownership and responsibility of the given jewelry very seriously. No matter the market value of the jewelry, be it made from gold and precious stones or plastic and string, we choose or sometimes have no choice but to invest highly in our attachment to certain pieces. And with that understanding it is not unimaginable to recognize the grief that someone might feel if they have been separated from a piece of jewelry that was given to them by a significant person.

Returning to the reading of Stephen’s review, it felt that much of the content of my lecture had also been “lost in translation” though perhaps in this case a better film analogy would be Total Recall, where the recollection of an event is not what it was hoped to be.