Arnoldsche published Bizarre Beauty, a book about William Harper, last year. AJF timed the release of this review of it to coincide with and celebrate an unrelated exhibition, Precious Grotesqueries: The Jewels of William Harper. That show will run October 23–December 12, 2025, at Les Enluminures.[1]

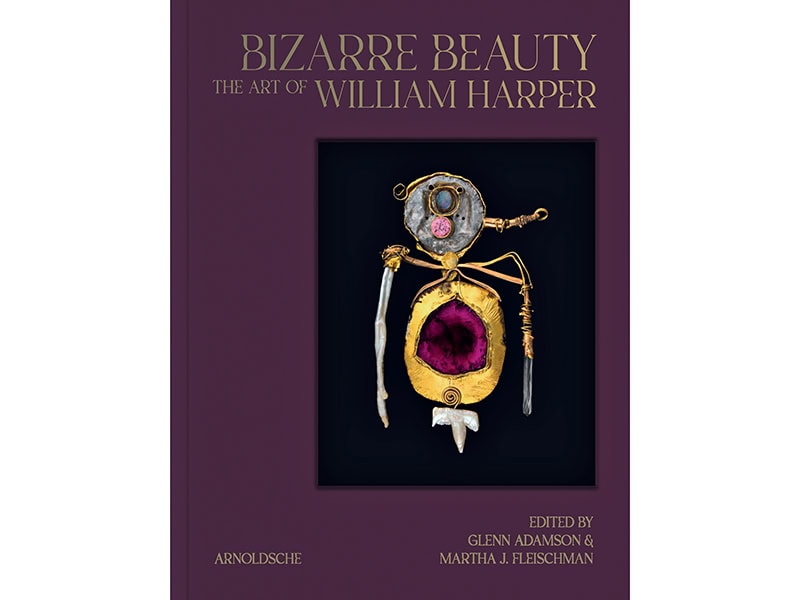

Glenn Adamson and Martha J. Fleischman (eds.), Bizarre Beauty: The Art of William Harper. Stuttgart: Arnoldsche, 2024.

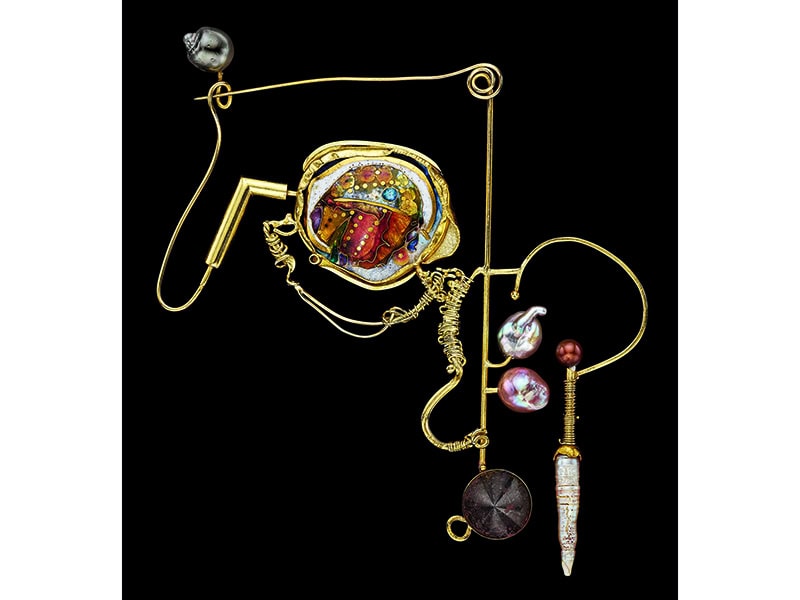

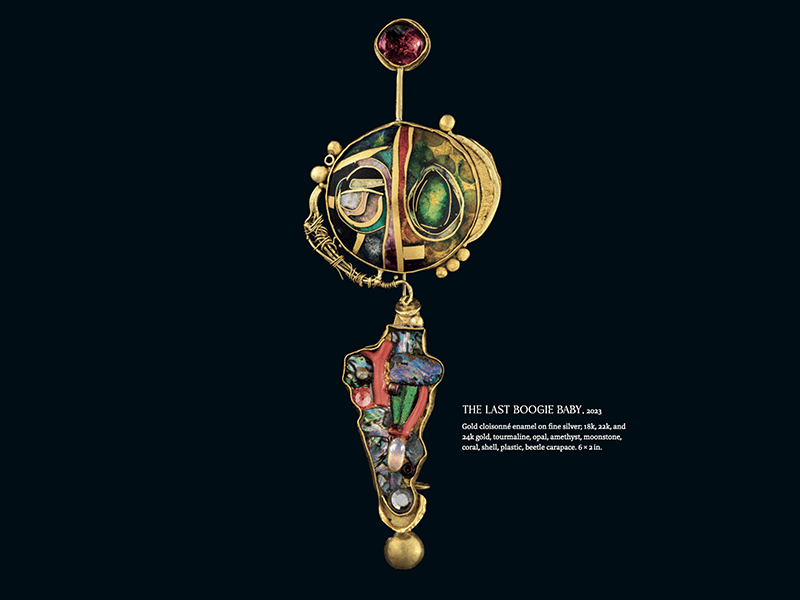

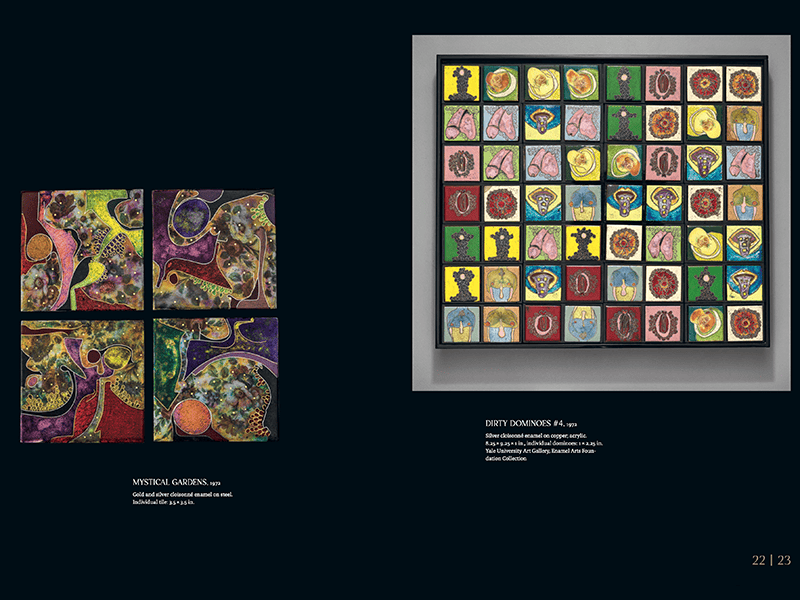

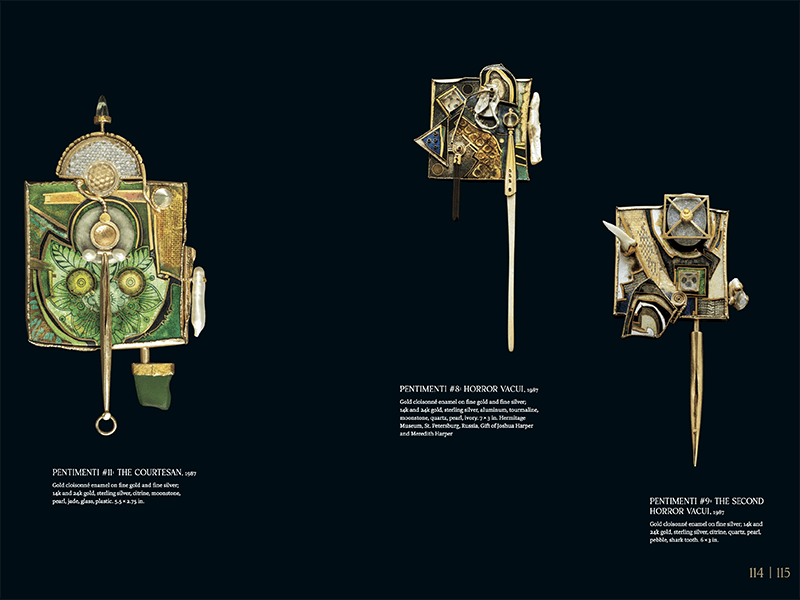

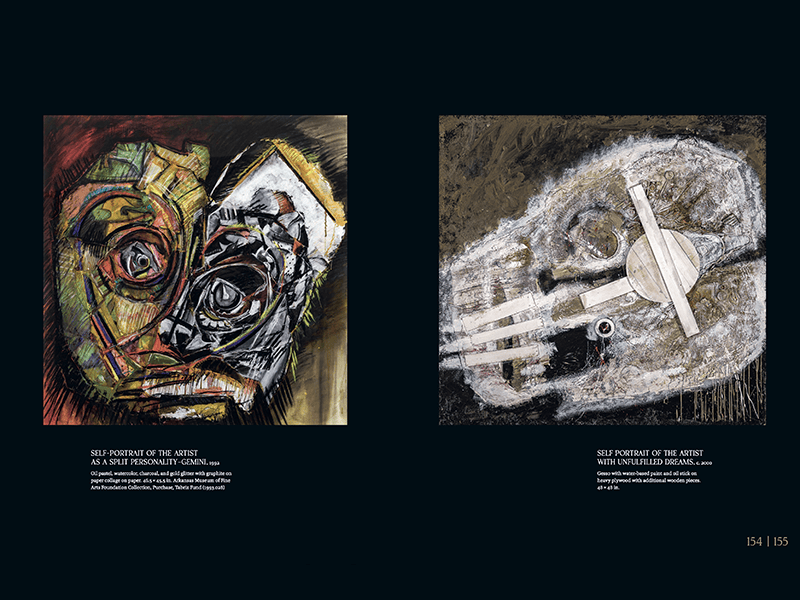

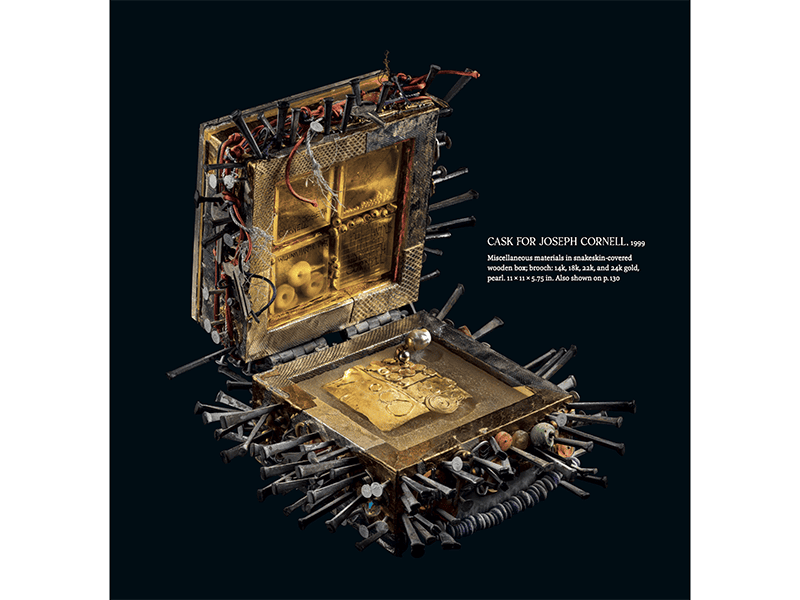

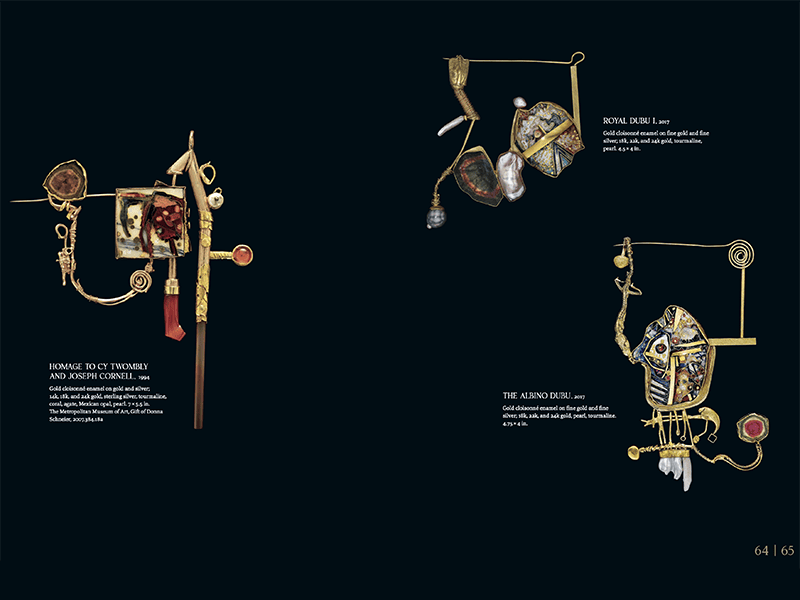

William Harper is a provocateur. His jewelry, objects, and paintings command attention and confront us with unexpected beauty and beguiling assemblages. He is good at this, and the book Bizarre Beauty: The Art of William Harper offers many examples of the ways in which Harper exploits his strategies, from emotive color work in enamels, “jewels,” and gems, to suggestive titles like The Brothel’s Favorite, with its erect shaft of aquamarine. His use of appropriation, recontextualizing natural objects like teeth and claws, feathers and fur, insects, shells, and even a small penis bone, plays with archetypes and elicits our visceral response. We are drawn in by pieces like Pagan Baby #10, with its striped beetle carapace suspended between natural pearls, serving as a scarab “jewel,” a pendant dangling from a fine gold and cloisonné enamel fibula brooch.

Harper is an icon of art jewelry and the studio craft movements. His career spans seven decades and his work is held in the collections of museums throughout the world, from the Metropolitan Museum in New York to the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, from the Cleveland Museum of Art to the Vatican Museum in Rome. A tremendously prolific artist whose work has been widely published, exhibited, and collected, Harper has been an influential and important figure for generations of jewelers, artists, and collectors.

Bizarre Beauty, edited by Glenn Adamson and Martha J. Fleischman, achieves in full what only the best artist books do. Published by Arnoldsche, this exquisite monograph is filled with striking images of bizarre beauty—gold and bones, hair and nails, all juxtaposed with extraordinary vitreous enamels. But Adamson and Fleischman have created so much more than a book of images. This book is quite special because of the important textual contributions that offer insights into the artist and the art, helping us understand and appreciate an entire lifetime of ideas, influences, and art works.

Ten authors contribute to this book and offer histories, anecdotes, and appreciation of Harper and his life’s work. Bizarre Beauty is an excellent artist book, and an important one. It captures Harper’s life and work. As such, this book is a cultural artifact with an important role that exceeds an historical document to inspire and inform artists, readers, and researchers of the future. Bizarre Beauty includes a narrative biography by Glenn Adamson, texts by Arthur C. Danto, Mary E. Davis, Toni Greenbaum, Cynthia Hahn, John Perreault, and William Harper, a conversation with Ugochukwu-Smooth Nzewi, a preface by Martha J. Fleischman, and a foreword by Abraham Thomas.

Adamson’s “Shape Shifter: The Lives of William Harper” is the central text, a poetic invitation written by a curator and historian who skillfully arranges events and influences like objects in an exhibition. Adamson contextualizes bodies of work within experiences from Harper’s life, starting with his childhood productions of puppetry and marionettes and carrying through to his studio in New York. It is quite a story—a self-described “strange little kid” who liked classical music and opera, attended Western Reserve University, discovered enamel and jewelry somewhat by chance, and spent a lifetime becoming a “pagan aesthete” who conjures up saints and martyrs, barbarians, and serpents in the form of jewelry.

In his text, Adamson allows himself the roles of biographer and narrator, speaking directly to us and sharing anecdotes and observations, while creating a shared experience with the reader. “This may be a good point to intervene in the narrative—just as Harper himself often has” leads us into a story of titles used to define works in series. “Back to the story now…” carries us into the history of shows at Kennedy Gallery in New York. “As mentioned briefly, above…” we learn that Harper began visiting Penland School of Craft in the late 60s, and soon after participated in an interdisciplinary workshop for instructors modeled after Black Mountain College. It led to new bodies of work, and life-long appreciation and interpretation of ethnographic objects and cultural artifacts.

Bizarre Beauty offers context for Harper’s work without seeking to “explain.” Internal and external forces both play their parts, and context is provided in the most complementary ways, suggesting the origins of works as part of the larger story of the artist’s life. The story wends its way from a secluded and rural life in small-town Bucyrus, OH, US, to Cleveland, then Florida State University, and ultimately New York City. The biography and extensive chronology help us understand important influences: art, theater, music, museums, and galleries. Harper shares that he uses his knowledge of the arts and culture to affect his intuitive approach to conceiving and creating his work. In one anecdote we learn that he “endured” a five-hour revival of “Einstein on the Beach,” by Robert Wilson and Philip Glass, to which he credits his abstract concept of “interludes,” a strategy he uses for developing “connective tissue” between longer series of work.

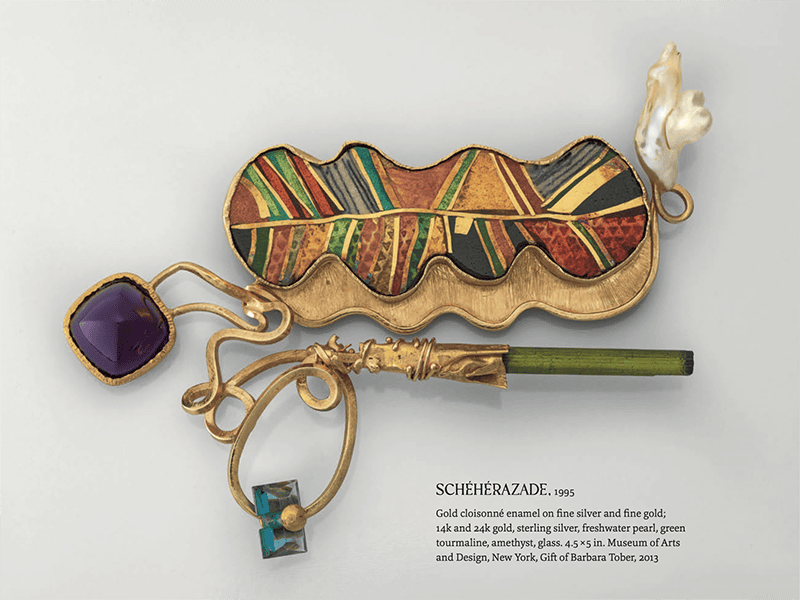

The 10 contributors’ texts address bodies of work without fear of taboo, the profane, or forbidden fruit. Like Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du Mal, Harper’s work reminds us of the ever-changing nature of beauty, “the flowers of evil,” and our morbid curiosity with the macabre. He pays homage to other artists and exalts anomalies in nature: Scheherazade, an exotic gold and cloisonné enamel brooch with amethyst and tourmaline, is inspired by the ballet that he has known and loved since childhood; Albino I, a gold and cloisonné enamel fibula brooch with pearls, reveres the pale in a palette inspired by the early works of Cy Twombly, which he had seen at the Met, and titled for the genetic condition.

The story also includes the evolution and trajectory of the artist’s practice. Harper’s work is about making objects that express our humanity, transcend time, and serve our fundamental need for art. Early in his career, his perception of “craft” and the work of his contemporaries played an important part in his effort to diverge and differentiate from what was happening in American craft. Harper recounts how, historically, the clean and minimal aesthetics of Scandinavian Modern gave way to new aesthetic values derived from research and experimentation with new materials and methods. He took a different path, however, seeking to imbue his works with the powerful emotional triggers he often experienced when looking at works from other cultures. He took risks, and he challenged more conventional approaches to working with found objects. Adamson notes: “Many jewelers have vigorously contested that bigotry of low expectations, but very few with Harper’s daring, nuance, and intellectual depth while operating entirely independently of what jewelry normally looks like or ‘should’ be.”

Home and studio are also an important part of William Harper’s story. As Churchill asserted in 1943, “We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us.” Art-making is much the same. Artists shape their studios and homes, which in turn shape them. In the biography we learn that Harper’s studio has always been at home, and has been the place where he has made all of his work. A photo provides a glimpse of his bench. Adamson describes his most recent visit to Harper’s studio: “Precious stones glowing with inner light sat in near orbit, as if they’d been pulled into his domain by gravitational attraction.” In the image of Harper’s workspace and bench, pieces of detritus share space with gems, jewels, and a variety of gold elements.

In the photo portrait of Harper and William Benjamin-Harper (his husband), he is surrounded by his collection of ethnographic objects, including a West African Senufo fertility doll, a gift from his first spouse in 1967, “a portent of things to come.” His home and studio provide the space that continues to shape what he draws, paints, and makes, where he thrives. To visit his home and studio via this book is an inspiring experience.

What about inspiration? Where does the work come from and how does the art develop? Like the pieces themselves, some answers are abstract: instinct, allusion, mythology, and religion, among others, all play a part. The artworks and the writing also offer suggestions about the effect of experiences in Harper’s life and his vast knowledge of the humanities as inspiration. Two of the texts by Harper offer more details. He opens the essay “Saints, Martyrs, and Savages” with “These pieces are about religion. They are not intended to be religious jewelry, nor are they anti-religious.” The book offers some intimate details, and leaves room for interpretation, just like the art itself.

The artist’s intent is arguably the core matter in the concerns of art discourse. What is the work about? “Intent” is thoughtfully revealed explicitly and sometimes implicitly throughout Bizarre Beauty. Glenn’s biography and the other essays help to address some of Harper’s intentions for the audience, while revealing his strategies to achieve them. Where historical references in titles and captions may be obscure or esoteric, a visceral response to the visual elements in the work is guaranteed from the reader.

Bizarre Beauty offers a deep and fantastic engagement with the art of William Harper. It is one man’s expression of holism: aesthetic, intellectual, psychological, social, and metaphysical, all parts of a beautiful whole, developed and revealed across decades of art and experiences. With great intelligence, this book sustains enigma, knowing full well the attraction of the ambiguous and the unknown.

[1] 23 East 73rd Street, New York, NY.

Reviews are the opinions of the authors alone, and do not necessarily express those of AJF.

We welcome your comments on our publishing, and will publish letters that engage with our articles in a thoughtful and polite manner. Please submit letters to the editor electronically; do so here. The page on which we publish Letters to the Editor is here.

© 2025 Art Jewelry Forum. All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. For reprint permission, contact info (at) artjewelryforum (dot) org