This essay was first delivered on a panel ‘Touch in Contemporary Art’ at the College Art Association, Los Angeles, in 2009, through travel funds provided by the Society of North American Goldsmiths. The paper was further developed into a lecture and presented at SOFA Chicago in November 2009 and subsequently presented at University of El Paso, Texas (2009), Pacific Northwest College of Art, Portland, Oregon (2009) Evergreen State College, Olympia, Washington (2010) and the University of Illinois, Champaign-Urbana (2010). The lecture has been modified to meet the format and needs of the AJF website.

As a museum curator, I work with objects. As a curator in a museum focused on contemporary craft, however, I spend a great deal of time thinking about how the environment and tools of the museum do – and do not – serve the kind of objects with which I work. According to Hilde Hein, author of The Museum in Transition: A Philosophical Perspective, ‘Objects have been reconstructed as sites of experience.’ (Hein 5) In other words, she argues, what has happened to objects in museum in recent decades is a ‘shift from ontological to phenomenological value.’ (Hein 15)

Three exhibitions demonstrate the shift that Hein describes. The first example is a room dedicated to porcelain at the Seattle Art Museum, a contemporary update of the cabinet of wonders, the model on which many of our capital ‘M’ museums are based. In this type of exhibition, objects are presented as examples of things made by humans – objects as categories of being, so to speak.

The next example is from Mining the Museum, a groundbreaking exhibition Fred Wilson created at the Maryland Historical Society in Baltimore in 1992. While Wilson was certainly not the first artist to critique the institutional context of a museum, his project used standard curatorial procedures to reveal a racialized American history. As Holland Cotter noted in the New York Times in 2004: ‘because museums tend to be conservative places, the stories are frequently soft and predictable, telling us things we basically already know and like to hear. Mr. Wilson, however, chose unusual, often unpretty things, and made them even more unusual by the way he combined them. The results were, in their undemonstrative way, eye-opening. In one vitrine, labeled ”Metalwork 1793-1880,” he placed ornate silver goblets and pitchers and iron slave shackles side by side. Elsewhere, he tucked a vintage Ku Klux Klan mask into an antique baby buggy. And in an installation titled ”Cabinetmaking 1820-1960” – reconstituted at the Studio Museum – he had four fancy parlor chairs attentively facing a cruciform wooden whipping post once used at a Maryland jail.’ (Cotter 2004)

This unexpected juxtaposition of objects revealed the ways in which objects function as carriers of socio-cultural meaning, and how the co-location of those objects as well as the modes of presentation can create, subvert, and magnify meaning.

And finally, the phenomenological experience as represented by an image of an Olafur Eliasson installation at San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. I saw this exhibition installed at MOMA in NY (Take Your Time: Olafur Eliasson, 2008), and found this image particularly compelling as the photograph makes solid what was a magical experience with light and color. It functions as a document of the exhibition but it does not, in fact, capture the sensation of being bathed in a slowly changing, light-filled room. It makes tangible an experience that was simultaneously personal and public.

Much like other museums dedicated to the visual arts – art, craft and/or design – one primarily encounters objects at the Museum of Contemporary Craft, the institution in which I work, from behind a barrier – typically under a protective cover or at a safe distance, as seen here in Generations: Ken Shores, 2008.

However, the objects exhibited at the museum at which I work are craft-based, meaning that physical engagement with the materials by the maker – and often by the ‘viewer’ – is vitally important. ‘Viewing’ – a term used to describe the way a visitor engages a painting – does not adequately encompass experiences with a craft-based object. For example, physically holding or turning over a painting or photograph does not typically alter one’s interpretation or experience of the such objects in a way that is critical to understanding the image itself. Turning over a piece of jewelry, however, can reveal a wealth of information, such as how the materials and physical form link the maker and the wearer’s body as a physical or imagined space, a critical element in understanding conceptually focused contemporary art jewelry.

Museums today are expected to fabricate experiences, to provide something that moves people beyond their daily lives, the mall and stores and, often, beyond the ways in which art is experienced in non-museum environments. To accomplish this, art museums employ a range of interpretive devices to connect audiences with objects on view – from guided tours to lectures, wall panels, catalogs, hands-on activities to demonstrations, websites, YouTube videos and workshops – all are designed to provide visitors with a deeper understanding of the artist and his or her artwork on view. As educating the public continues to be as important – if not more so – than collecting itself, museum professionals seek creative ways to provide visitors with experiences around objects while simultaneously protecting work for future generations.

A curator’s ‘toolkit’ for the display of objects, craft and non-craft alike, includes a number of basic elements: covered pedestals, wall cases, plinths and shelves, or casework, all modified to set a particular stage and choreography of movement through an exhibition setting.

In recent jewelry exhibitions at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, University of Oregon, San Francisco Museum of Craft + Design and Museum of Contemporary Craft, Portland, elements from a curatorial ‘toolkit’ clearly protect objects and fulfill their function and purpose of placing objects on view, but also present interactive work in a mode designed for the display of objects to be looked at or viewed. These props also reify the role of the museum as a mediator between the displayed objects and the museum visitor. In most art museums, a docent or a guide, then, serves as a critical conduit for communication between the visitor and both the unseen artist and the artist’s object on display. Playing a crucial role as educator and interpreter of object and experience, interactions of such a kind further distance audiences from the actual experience of handling or wearing art jewelry.

One of the most exciting aspects of working in museums today is institutional diversity. And in terms of craft, this is even more exciting given the range of kinds of institutions now collecting, preserving and exhibiting craft-based objects. A brief survey of the museumscape currently engaging in the exhibition of art jewelry is essential to frame an understanding of how the exhibition, on which I will focus later in this paper, fits into and challenges exhibition strategies currently in place in museums in the United States at this time.

At three encyclopedic museums – the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston – curators of decorative arts enact critical roles in collection stewardship, leading exhibition and collection building programs through recently established and vitally important curatorial positions. The role of these institutions is to establish and to present a canon of visual arts in which the institution collects and presents examples of works that are agreed upon by many curators, scholars and artists to be the finest examples of particular visual works.

Regional art museums across the country are playing a critical role, too – including such institutions as the Racine Museum of Art, Wisconsin, the Mint Museum, Charlotte, North Carolina and Tacoma Art Museum, Washington. These museums place the regional within national and global contexts, serving an important documentary yet different need and focus than the larger institutions. Such institutions add another dimension and layer to discourse, as well as critical primary research to document regional differences.

Even within those that focus specifically on craft-based work, there are museums with diverse exhibition practices. Here are two examples of a larger and a smaller institutions from each coast: the Museum of Arts & Design (MAD), New York and the Society of Contemporary Craft, Pittsburgh; and the Bellevue Arts Museum, Washington and Museum of Contemporary Craft, Portland, Oregon.

Although museum curators are trained to exhibit work in particular ways, the individual missions and focus of each kind of museum require different kinds of exhibition practices. In other words, museums are not all alike and they can’t – nor should they – each present work in the same way. From encyclopedic to contemporary, academic to media-specific, each institution serves a vital role in the diverse ecosystem of the visual arts. And curators these institutions have been able, in recent years, to actively shape the way craft – art jewelry in particular – is exhibited within the institutional context of museums.

First, I’d like to discuss how large, encyclopedic museums most often present collections. In this installation view of the Daphne Farago Collection as presented at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, we see how this kind of museum enacts its mission and imperative to steward objects in perpetuity. Enshrined in a series of brightly lit cases within a darkened room, this exhibition setting creates a sense of awe and wonder, highlighting the preciousness of the works on view. What this exhibition creates is a feeling that contemporary art jewelry is an artifact.

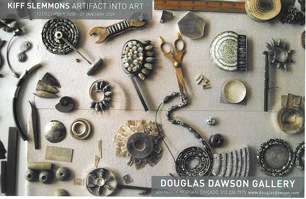

The presentation of contemporary art jewelry in this format works well for an artist like Kiff Slemmons. In fact, this advertisement for a gallery show spells it out quite perfectly: Artifact into Art. For Slemmons, this makes sense in terms of how her work mines history and how works like hers can be best displayed, but is this true for most contemporary art jewelry?

The layout and presentation of objects within the cases of such museum installations as that at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston remind me of the types of visual displays used in the nineteenth century to show jewelry from around the world – as seen in this page for an international exhibition held in London, United Kingdom, in 1862.

Which brings me back to the first exhibitions I mentioned: the porcelain room at the Seattle Art Museum, and Fred Wilson’s installation. If we curators are showing contemporary work in the format of the wunderkammer or the cabinet of curiosities, what does that mean? What kinds of colonial discourses and anthropological associations are inadvertently constructed? How are we structuring the experience and understanding of contemporary art jewelry? In ways that define it as art, artifact, or something in between?

A range of installations, from the Native American silver from the Denver Art Museum to the World Jewelry Museum in Seoul, Korea, are particularly anthropological, yet not far off from installations of contemporary art jewelry commonly found throughout museums today.

While the installation of the jewelry collection at MAD, New York, does allow circumnavigation of the objects on view, the design here, too, is still is laid out in much the same anthropological, artifact style. What this exhibition format does is turn three-dimensional objects into flattened two-dimensional works to be looked at and contemplated – like paintings. When installed in this way, we curators ask visitors to engage contemporary art jewelry in the same was we engage precious artworks in a museum which cannot be touched.

Smaller contemporary works are often presented encased in large vitrines, much like these larger works on view in the Menil collection, Houston, Texas. Presented in this way, these works from 1975, on view in Ornament as Art: Avant-Garde Jewelry from the Helen Williams Drutt Collection, as seen on view at the Smithsonian Institution’s Renwick Gallery (2008), read as relics or ethnographic sculptures-in-miniature.

Even the way we represent objects in photographs linked to museum exhibitions removes them from almost all contexts, again presenting them as isolated artifacts or objects as seen on the website page documenting Ornament as Art. Isolation in exhibitions or photography works for contemporary sculpture because such works are meant to stand alone and to be looked at. Contemporary art jewelry, on the other hand, has sculptural qualities, but the relationship each of these objects has to a real or implied body makes these works something more than objects to be merely looked at. While much contemporary art jewelry deliberately challenges the idea of wearability or touch, for the sake of this paper and the argument I am constructing to encourage curators to re-define and re-think the exhibition of such works, I am limiting my focus here to a category of contemporary art jewelry which clearly relates to the historic forms of jewelry as adornment.

Let me digress for a moment to reiterate my point regarding context, moving from a discussion of presentation from the museum to print. In the February/March issue of American Craft, a multi-page article featuring the studio space and work of Jan Yager begins with a two-page spread. (Shannon 114-117) Posing near her tools, the implication of the process of making is made clearly visible. Surrounding her workbench and tools are a plethora of images – space populated by inspiration for her work. We see the crack vials that are cultural residue of the urban environment in which she lives and works and the source of some of her work.

Yet when we photograph the work, present it for distribution in print, it is isolated from all the richness that went into its making, with the assumption that viewers will be interested enough to engage the work beyond a cursory glance. The removal of traces of making, wearing, or other contexts results in an image of an object that resists engagement beyond the subculture of those educated about both contemporary art and/or contemporary art jewelry.

The second example of presentation of jewelry in a museum setting comes from the model of the ‘white cube’, the quintessential white-walled, brightly lit and minimally populated contemporary art space. Co-curated by Kate Wagle and Anya Kivarkis, the exhibition The Thinking Body, seen here installed at the San Francisco Museum of Craft + Design, is a strong example of a thematic, conceptually driven contemporary art jewelry exhibition. The objects here are presented in a pared down format that makes them the focus of theoretical and analytic attention. In academically rigorous exhibitions like this, contemporary art jewelry serves as a vehicle to explore the idea of the relationship between the object and the idea of the body in which the body itself is an imagined space or entity.

The third example is taken from Equilibrium: Body as Site, Metalsmith magazine’s 2008 exhibition-in-print turned into an exhibition-on-view at the Rubin Center, UTEP. Co-curated by Kate Bonansinga and Rachelle Thiewes, the exhibition centers around the idea of the five senses in what the co-curators describe as privileging ‘the sensorial over the intellectual, bucking the tide of the past several decades of art interpretation, which has favored the intellectualization of art practice and experience.’ (Bonansinga and Thiewes)

Here we get something in between the examples I’ve shared thus far. The exhibition centralizes the body, but unlike the pristine white cube, the strategic use of color and engagement of a range of curatorial tools for display and well-designed didactics trigger connections between the objects, resulting in a different kind of understanding of the relationship between the objects on view and wearability. The website uses photography differently – here it functions as a means of showing how the jewelry is physically engaged through a slideshow. When coupled with the exhibition signage, a visitor could clearly understand which works were available for physical interaction and which are meant to be exclusively viewed and for imagined experiences.

In contrast to art and/or craft museums, science centers are often understood to offer a less passive and differently mediated experience. According to Hilde Hein, science center exhibits are ‘designed to provoke and gratify inquisitiveness rather than to institute awe.’ (Hein 27) To create meaning, Hein argues, the visitor must ‘interact both physically and mentally with an exhibit in order to complete its performance and render it meaningful.’ (Hein 27) This raises an interesting question. How might a museum focused on the visual arts offer an interactive experience that rewards physical and mental engagement? Knowing that kinesthetic knowledge is a vital element in the creation of a craft object, how can a museum provide an experience that recognizes the importance of physical touch while still preserving its collection for future generations?

And then, too, in comparison with such exhibitions as AngloMania: Tradition and Transgression in British Fashion, an exhibition organized by the Costume Institute at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (2006) we might ask how curators can bring a socio-cultural context back into our understanding of craft-based objects. What models might be found in these types of alternative, historically-influenced yet updated dioramas, upon which we can draw?

As curators who present exhibitions of contemporary art jewelry, we run the risk of forgetting not only the artists and the processes of making but the experiences of those who have the exquisite privilege of wearing this kind of work in their everyday lives. Such women as Daphne Farago and Helen Williams Drutt are just two examples of many women who collect avant-garde and contemporary art jewelry, wear it and have now made sure that their collections are housed in museums where the works can be preserved and shared with future generations. As a marker of identity – and, in the case of Peggy Guggenheim’s deliberate adornment of one earring by Alexander Calder and another by Yves Tanguy to an opening in 1942, a marker of the politics of aesthetics – contemporary art jewelry is broadly recognized as portable art. (Walsh) For the majority of the public-at-large, however, the opportunity to handle, let alone wear or collect contemporary art jewelry is out of reach, raising important questions about how the presentation of exhibitions in publicly-focused museums must provide imagined experiences to many who have little personal experience to translate what is on view into a real experience.

So how did we at the Museum of Contemporary Craft work to create an exhibition in response to many of these critical conundrums? In response to these questions, the Museum of Contemporary Craft developed Touching Warms the Art, an interactive and collaboratively executed exhibition. (The title of this exhibition is a play on signage used in the Tacoma Art Museum and adopted by the Museum of Contemporary Craft in 2005 to help visitors understand why handling artwork is discouraged: Touching Harms the Art.) Paired with Framing* The Art of Jewelry, an exhibition in print curated by Ellen Lupton for the Society of North American Goldsmiths and published in Metalsmith magazine, the presentation of these two exhibitions together provided visitors with three primary ways in which studio art jewelry is most often experienced today: in print, in exhibition and through interaction.

Touching Warms the Art was developed in response to a third, earlier exhibition, Beyond the Body: Northwest Jewelers at Play (2005), organized by Rock Hushka, curator at the Tacoma Art Museum. Prompted by Rebecca Scheer’s review of the exhibition published in Metalsmith magazine, a friend and colleague who is both a studio jeweler and an instructor at Oregon College of Art and Craft, Touching Warms the Art developed out of, in response to and in dialogue with questions and issues from both Beyond the Body and Scheer’s provocative questions. In her review, Scheer examined the ways in which Beyond the Body addressed the challenges involved in the exhibition of art jewelry. She noted that: ‘The labels warning visitors not to handle the jewelry in this exhibition read “Touching Harms the Art.” Apparently, the curator finds this statement applied to jewelry ironic (albeit necessary) and included an interactive component welcoming visitors to ‘experience what it feels like to wear studio art jewelry.’ Four sculpture students from the Tacoma School of the Arts were invited by the museum to make jewelry for visitors to handle. . . .’ (Scheer 53)

Scheer revisited these issues in the conclusion to her review, with a direct challenge to both makers and exhibitors of art jewelry. She wrote: ‘Here’s a heavy thought about the audience response to the touchable work: imagine if each of the studio jewelers created a non-precious piece for visitors to handle. Could we professionals even achieve such working freedom? Does it devalue what we do? Painstaking craft and hand-worked detail may be the forte of the craft artist. Nevertheless, these values generate preciousness, ultimately dividing the masses from experiencing the pleasure of “real” studio jewelry first-hand.’ (Scheer 53)

Scheer’s review reminded me that curators and artists often view the same art environment and experience very differently. From my perspective, the Tacoma Art Museum offered a viable solution in Beyond the Body – an interactive display of art jewelry created by sculpture students working under the guidance of noted art jewelry Nancy Worden. Engaging an artist from the exhibition to create a related, interactive feature is an approach which extends the conceptual aspects of the exhibition while protecting the collection. But Scheer’s review revealed that such features may not function as intended – particularly in terms of craft-based artwork. Scheer described the same interactive feature in her review as a ‘petting zoo’, lamenting the way it distracted and diverted visitors from the artwork on view. (Scheer 53) Her comments were a provocative reminder that substitutions for first-hand experiences may not always succeed as educational devices within a museum setting. She rightly points out that interaction can be far more rewarding than an imagined experience. She notes, too, that the substitution of ‘amateur’ work for ‘skilled’ work does not necessarily provide an adequate visitor experience. Her challenge asked artists to put craft back into the hands of everyday people, to democratize what has become the privileged realm of the elite and for museums to consider what it means to provide an experience that matches the high level of craftsmanship and the unique conceptual and physical qualities of the objects being presented.

Together, Scheer and I established a general working premise for this exhibition that art jewelry is meant to be worn – touched. Artists were invited through a call for entries to put aside precious and fragile materials and instead to create designs using unexpected materials and construction techniques. Selected works needed to withstand physical handling by museum visitors over a period of several months, and, after the exhibition, works would become the foundation of the museum’s teaching collection. Working together, we reached a compromise by which visitors could directly experience the relational aspects of art jewelry – interaction between the object, wearer and the spectator.

Scheer and I invited Rachelle Thiewes, professor of metal arts at University of Texas, El Paso, to jury submissions with us. Known for body-conscious, sculptural jewelry that carefully considers line, movement and form, Thiewes is also a collector of art jewelry. Perhaps more importantly, she is known for wearing her collection – even ‘difficult’ artwork – every single day, sporting a Gijs Bakker neckpiece regardless of whether she is teaching, working in the studio, hiking or running to grab a Dr Pepper at the convenience store. Out of 145 submissions from seventeen countries, we selected work by 67 artists from twelve counties.

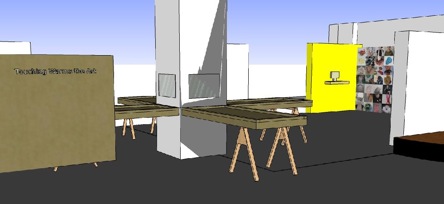

The design of the installation needed to match the exhibition’s conceptual focus as well. Constructed with re-usable honeycomb cardboard, typically a packing material, we created an open, inviting, and non-hierarchical installation. Pegs on walls held neckpieces, while rings, brooches, and bracelets resided on cardboard ‘tabletops’ resting on sawhorses.

Using images submitted by participating artists, wallpapers were created to provide a backdrop for the exhibition and to help visitors by serving as a visual ‘cheat sheet’ for possible ways to wear the jewelry.

Recognizing that individual experience – and the ‘performance’ of wearing art jewelry – are critical elements in a project like this, visitors were invited to try work on, to view themselves in mirrors and to take pictures of themselves at a photo kiosk. All of the pictures were uploaded to a Flickr site, from which visitors – and participating artists – could gain access to and better understand the relationships between object and wearer, display and portability.

Extending individual experience further, an ‘art bar’ – fully stocked with materials, tools and books – was also available for visitors to try their own hand at making and wearing art jewelry.

Over the course of the exhibition, not one piece was stolen. And magically, visitors began creating their own pieces and ‘installing’ them on the art bar wall, adding their own creations to the collective experience of the exhibition.

Here is how people experienced the exhibitions. Downstairs, we juxtaposed the printed pages from Metalsmith magazine that formed the Framing* The Art of Jewelry exhibition with selected objects from Ellen Lupton’s visual essay. Lupton draws heavily upon Jacques Derrida’s ideas about supplemental forms, drawing out the relationships between the picture frame, the pedestal, and the liminal zone, between letters on a page as tools that both bind and stage in much the same way an art jeweler creates a setting. (Lupton 11) Several of the artists included in Framing* provided work for Touching Warms the Art in direct response to Rebecca Scheer’s Metalsmith review cited earlier, in which she raised a question regarding the invitation to artists to create work to be handled by the public-at-large.

Certainly, there was a campy performance and dress-up element of play involved in this exhibition – particularly with the addition of the camera and ability to photograph. But what was truly exciting was the boundary crossing that occurred. Most intriguing – people talked to one another. Strangers conversed as they encouraged each other to touch a piece, to try it on, shared their surprise at textures, materials or processes and paid attention to how objects looked on each other. When is the last time you casually conversed – for an extended period of time – with other visitors at a contemporary art exhibition? From babies to teens to the middle-aged to the elderly and between girls and boys to women and men, all ranges of ages and genders actively participated in the exhibition. Visitors found new and unexpected ways of wearing the jewelry.

After seeing Flickr photos of how her work was being engaged, artist Gail Ralston remarked on her blog: ‘The really great part is that the museum has set up a camera to take pictures of people wearing the jewelry, so the artists get to see people interacting with their pieces. Here are a few shots of my “bracelet” being worn. I’m beginning to think I should have made it a headpiece.’ (Ralston) By making the Flickr archive publicly available, the images provide critical connections between artist and audience as much as between audience and the museum as the site of experience.

Visitors embraced the dialogic aspects of the exhibition, inventing ways to allow two or even four people to collaboratively wear a single piece. Sometimes it was less about what was worn than about how much could be piled on at one time. The kiosk often functioned like a photo booth, where visitors were clearly taking a souvenir shot to document a shared day and unique experience. The performative aspects of art jewelry were clearly understood, as many tried on different personas triggered by the art jewelry being worn.

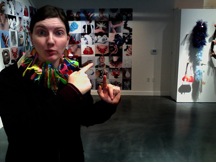

Still others not only performed, but used the camera as a special tool. Here, Lindsay Huff uses her hands to frame the picture of herself wearing her gelato spoon charm necklace – while taking a new picture of herself adorned. Animator Jason Giglio took a series of stills to create a stop action film from his Flickr photos with Cristina Dias’s work, inviting YouTube comments on his new hat. Eleven fashion designers from Portland selected works from the exhibition, using them as inspiration for the creation of one-of-a-kind garments – including Portland’s own Leanne Marshall, winner of a season of Project Runway. Where visitors downstairs physically put their hands behind their backs or clasped them in front of themselves, upstairs anything was possible. (oye)

One reviewer of the exhibition wondered, ‘If an object is created for a specific purpose, but it never gets to fulfill that purpose, if it’s never used or touched (never imbued with memory), does it become something else? Does it lose its true meaning?’ (Verzemnieks 2008) Rather than create props or rely on imagined experiences, our exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Craft placed studio art jewelry directly into the hands of visitors of all ages and a broad range of educational backgrounds. Centralizing the unique aspects of craft at the center of an experiential exhibition pushes museum practice to engage in what Glenn Adamson argues for: the museum treatment of craft ‘as a subject, not a category . . . not something to be pushed into the background or seen in relationship to other objects, but rather a topic for conceptualization.’ (Adamson 110)

Returning to the original image and argument that the shift in museums in recent years has been from the presentation of objects as markers of experience to experience itself, it seems clear to me that museum curators today have easily mastered the ontological types of presentations. Touching Warms the Art then swings the pendulum far, far into engagement. Now the opportunity remains to do something in between – or perhaps entirely new – that brings exhibition practices into a new middle ground where the socio-cultural contexts of making, wearing, protecting and displaying contemporary art jewelry may be better explored.

In conclusion, I would like to extend an idea proposed by Robert Storr from art museums to craft museums. (Storr 14) While Storr argues that ‘Showing is telling’, I believe that this exhibition demonstrates that ‘Showing is telling, but with art jewelry, touching might tell you more.’

This essay was first delivered on a panel ‘Touch in Contemporary Art’ at the College Art Association, Los Angeles, in 2009, through travel funds provided by the Society of North American Goldsmiths. The paper was further developed into a lecture and presented at SOFA Chicago in November 2009 and subsequently presented at University of El Paso, Texas (2009), Pacific Northwest College of Art, Portland, Oregon (2009) Evergreen State College, Olympia, Washington (2010) and the University of Illinois, Champaign-Urbana (2010). The lecture has been modified to meet the format and needs of the AJF website.

Three exhibitions demonstrate the shift that Hein describes. The first example is a room dedicated to porcelain at the Seattle Art Museum, a contemporary update of the cabinet of wonders, the model on which many of our capital ‘M’ museums are based. In this type of exhibition, objects are presented as examples of things made by humans – objects as categories of being, so to speak.

The next example is from Mining the Museum, a groundbreaking exhibition Fred Wilson created at the Maryland Historical Society in Baltimore in 1992. While Wilson was certainly not the first artist to critique the institutional context of a museum, his project used standard curatorial procedures to reveal a racialized American history. As Holland Cotter noted in the New York Times in 2004: ‘because museums tend to be conservative places, the stories are frequently soft and predictable, telling us things we basically already know and like to hear. Mr. Wilson, however, chose unusual, often unpretty things, and made them even more unusual by the way he combined them. The results were, in their undemonstrative way, eye-opening. In one vitrine, labeled ”Metalwork 1793-1880,” he placed ornate silver goblets and pitchers and iron slave shackles side by side. Elsewhere, he tucked a vintage Ku Klux Klan mask into an antique baby buggy. And in an installation titled ”Cabinetmaking 1820-1960” – reconstituted at the Studio Museum – he had four fancy parlor chairs attentively facing a cruciform wooden whipping post once used at a Maryland jail.’ (Cotter 2004)

And finally, the phenomenological experience as represented by an image of an Olafur Eliasson installation at San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. I saw this exhibition installed at MOMA in NY (Take Your Time: Olafur Eliasson, 2008), and found this image particularly compelling as the photograph makes solid what was a magical experience with light and color. It functions as a document of the exhibition but it does not, in fact, capture the sensation of being bathed in a slowly changing, light-filled room. It makes tangible an experience that was simultaneously personal and public.

However, the objects exhibited at the museum at which I work are craft-based, meaning that physical engagement with the materials by the maker – and often by the ‘viewer’ – is vitally important. ‘Viewing’ – a term used to describe the way a visitor engages a painting – does not adequately encompass experiences with a craft-based object. For example, physically holding or turning over a painting or photograph does not typically alter one’s interpretation or experience of the such objects in a way that is critical to understanding the image itself. Turning over a piece of jewelry, however, can reveal a wealth of information, such as how the materials and physical form link the maker and the wearer’s body as a physical or imagined space, a critical element in understanding conceptually focused contemporary art jewelry.

A curator’s ‘toolkit’ for the display of objects, craft and non-craft alike, includes a number of basic elements: covered pedestals, wall cases, plinths and shelves, or casework, all modified to set a particular stage and choreography of movement through an exhibition setting.

In recent jewelry exhibitions at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, University of Oregon, San Francisco Museum of Craft + Design and Museum of Contemporary Craft, Portland, elements from a curatorial ‘toolkit’ clearly protect objects and fulfill their function and purpose of placing objects on view, but also present interactive work in a mode designed for the display of objects to be looked at or viewed. These props also reify the role of the museum as a mediator between the displayed objects and the museum visitor. In most art museums, a docent or a guide, then, serves as a critical conduit for communication between the visitor and both the unseen artist and the artist’s object on display. Playing a crucial role as educator and interpreter of object and experience, interactions of such a kind further distance audiences from the actual experience of handling or wearing art jewelry.

At three encyclopedic museums – the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston – curators of decorative arts enact critical roles in collection stewardship, leading exhibition and collection building programs through recently established and vitally important curatorial positions. The role of these institutions is to establish and to present a canon of visual arts in which the institution collects and presents examples of works that are agreed upon by many curators, scholars and artists to be the finest examples of particular visual works.

Regional art museums across the country are playing a critical role, too – including such institutions as the Racine Museum of Art, Wisconsin, the Mint Museum, Charlotte, North Carolina and Tacoma Art Museum, Washington. These museums place the regional within national and global contexts, serving an important documentary yet different need and focus than the larger institutions. Such institutions add another dimension and layer to discourse, as well as critical primary research to document regional differences.

Although museum curators are trained to exhibit work in particular ways, the individual missions and focus of each kind of museum require different kinds of exhibition practices. In other words, museums are not all alike and they can’t – nor should they – each present work in the same way. From encyclopedic to contemporary, academic to media-specific, each institution serves a vital role in the diverse ecosystem of the visual arts. And curators these institutions have been able, in recent years, to actively shape the way craft – art jewelry in particular – is exhibited within the institutional context of museums.

First, I’d like to discuss how large, encyclopedic museums most often present collections. In this installation view of the Daphne Farago Collection as presented at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, we see how this kind of museum enacts its mission and imperative to steward objects in perpetuity. Enshrined in a series of brightly lit cases within a darkened room, this exhibition setting creates a sense of awe and wonder, highlighting the preciousness of the works on view. What this exhibition creates is a feeling that contemporary art jewelry is an artifact.

The layout and presentation of objects within the cases of such museum installations as that at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston remind me of the types of visual displays used in the nineteenth century to show jewelry from around the world – as seen in this page for an international exhibition held in London, United Kingdom, in 1862.

Which brings me back to the first exhibitions I mentioned: the porcelain room at the Seattle Art Museum, and Fred Wilson’s installation. If we curators are showing contemporary work in the format of the wunderkammer or the cabinet of curiosities, what does that mean? What kinds of colonial discourses and anthropological associations are inadvertently constructed? How are we structuring the experience and understanding of contemporary art jewelry? In ways that define it as art, artifact, or something in between?

While the installation of the jewelry collection at MAD, New York, does allow circumnavigation of the objects on view, the design here, too, is still is laid out in much the same anthropological, artifact style. What this exhibition format does is turn three-dimensional objects into flattened two-dimensional works to be looked at and contemplated – like paintings. When installed in this way, we curators ask visitors to engage contemporary art jewelry in the same was we engage precious artworks in a museum which cannot be touched.

Even the way we represent objects in photographs linked to museum exhibitions removes them from almost all contexts, again presenting them as isolated artifacts or objects as seen on the website page documenting Ornament as Art. Isolation in exhibitions or photography works for contemporary sculpture because such works are meant to stand alone and to be looked at. Contemporary art jewelry, on the other hand, has sculptural qualities, but the relationship each of these objects has to a real or implied body makes these works something more than objects to be merely looked at. While much contemporary art jewelry deliberately challenges the idea of wearability or touch, for the sake of this paper and the argument I am constructing to encourage curators to re-define and re-think the exhibition of such works, I am limiting my focus here to a category of contemporary art jewelry which clearly relates to the historic forms of jewelry as adornment.

Yet when we photograph the work, present it for distribution in print, it is isolated from all the richness that went into its making, with the assumption that viewers will be interested enough to engage the work beyond a cursory glance. The removal of traces of making, wearing, or other contexts results in an image of an object that resists engagement beyond the subculture of those educated about both contemporary art and/or contemporary art jewelry.

The third example is taken from Equilibrium: Body as Site, Metalsmith magazine’s 2008 exhibition-in-print turned into an exhibition-on-view at the Rubin Center, UTEP. Co-curated by Kate Bonansinga and Rachelle Thiewes, the exhibition centers around the idea of the five senses in what the co-curators describe as privileging ‘the sensorial over the intellectual, bucking the tide of the past several decades of art interpretation, which has favored the intellectualization of art practice and experience.’ (Bonansinga and Thiewes)

In contrast to art and/or craft museums, science centers are often understood to offer a less passive and differently mediated experience. According to Hilde Hein, science center exhibits are ‘designed to provoke and gratify inquisitiveness rather than to institute awe.’ (Hein 27) To create meaning, Hein argues, the visitor must ‘interact both physically and mentally with an exhibit in order to complete its performance and render it meaningful.’ (Hein 27) This raises an interesting question. How might a museum focused on the visual arts offer an interactive experience that rewards physical and mental engagement? Knowing that kinesthetic knowledge is a vital element in the creation of a craft object, how can a museum provide an experience that recognizes the importance of physical touch while still preserving its collection for future generations?

And then, too, in comparison with such exhibitions as AngloMania: Tradition and Transgression in British Fashion, an exhibition organized by the Costume Institute at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (2006) we might ask how curators can bring a socio-cultural context back into our understanding of craft-based objects. What models might be found in these types of alternative, historically-influenced yet updated dioramas, upon which we can draw?

As curators who present exhibitions of contemporary art jewelry, we run the risk of forgetting not only the artists and the processes of making but the experiences of those who have the exquisite privilege of wearing this kind of work in their everyday lives. Such women as Daphne Farago and Helen Williams Drutt are just two examples of many women who collect avant-garde and contemporary art jewelry, wear it and have now made sure that their collections are housed in museums where the works can be preserved and shared with future generations. As a marker of identity – and, in the case of Peggy Guggenheim’s deliberate adornment of one earring by Alexander Calder and another by Yves Tanguy to an opening in 1942, a marker of the politics of aesthetics – contemporary art jewelry is broadly recognized as portable art. (Walsh) For the majority of the public-at-large, however, the opportunity to handle, let alone wear or collect contemporary art jewelry is out of reach, raising important questions about how the presentation of exhibitions in publicly-focused museums must provide imagined experiences to many who have little personal experience to translate what is on view into a real experience.

So how did we at the Museum of Contemporary Craft work to create an exhibition in response to many of these critical conundrums? In response to these questions, the Museum of Contemporary Craft developed Touching Warms the Art, an interactive and collaboratively executed exhibition. (The title of this exhibition is a play on signage used in the Tacoma Art Museum and adopted by the Museum of Contemporary Craft in 2005 to help visitors understand why handling artwork is discouraged: Touching Harms the Art.) Paired with Framing* The Art of Jewelry, an exhibition in print curated by Ellen Lupton for the Society of North American Goldsmiths and published in Metalsmith magazine, the presentation of these two exhibitions together provided visitors with three primary ways in which studio art jewelry is most often experienced today: in print, in exhibition and through interaction.

Touching Warms the Art was developed in response to a third, earlier exhibition, Beyond the Body: Northwest Jewelers at Play (2005), organized by Rock Hushka, curator at the Tacoma Art Museum. Prompted by Rebecca Scheer’s review of the exhibition published in Metalsmith magazine, a friend and colleague who is both a studio jeweler and an instructor at Oregon College of Art and Craft, Touching Warms the Art developed out of, in response to and in dialogue with questions and issues from both Beyond the Body and Scheer’s provocative questions. In her review, Scheer examined the ways in which Beyond the Body addressed the challenges involved in the exhibition of art jewelry. She noted that: ‘The labels warning visitors not to handle the jewelry in this exhibition read “Touching Harms the Art.” Apparently, the curator finds this statement applied to jewelry ironic (albeit necessary) and included an interactive component welcoming visitors to ‘experience what it feels like to wear studio art jewelry.’ Four sculpture students from the Tacoma School of the Arts were invited by the museum to make jewelry for visitors to handle. . . .’ (Scheer 53)

Scheer revisited these issues in the conclusion to her review, with a direct challenge to both makers and exhibitors of art jewelry. She wrote: ‘Here’s a heavy thought about the audience response to the touchable work: imagine if each of the studio jewelers created a non-precious piece for visitors to handle. Could we professionals even achieve such working freedom? Does it devalue what we do? Painstaking craft and hand-worked detail may be the forte of the craft artist. Nevertheless, these values generate preciousness, ultimately dividing the masses from experiencing the pleasure of “real” studio jewelry first-hand.’ (Scheer 53)

Scheer’s review reminded me that curators and artists often view the same art environment and experience very differently. From my perspective, the Tacoma Art Museum offered a viable solution in Beyond the Body – an interactive display of art jewelry created by sculpture students working under the guidance of noted art jewelry Nancy Worden. Engaging an artist from the exhibition to create a related, interactive feature is an approach which extends the conceptual aspects of the exhibition while protecting the collection. But Scheer’s review revealed that such features may not function as intended – particularly in terms of craft-based artwork. Scheer described the same interactive feature in her review as a ‘petting zoo’, lamenting the way it distracted and diverted visitors from the artwork on view. (Scheer 53) Her comments were a provocative reminder that substitutions for first-hand experiences may not always succeed as educational devices within a museum setting. She rightly points out that interaction can be far more rewarding than an imagined experience. She notes, too, that the substitution of ‘amateur’ work for ‘skilled’ work does not necessarily provide an adequate visitor experience. Her challenge asked artists to put craft back into the hands of everyday people, to democratize what has become the privileged realm of the elite and for museums to consider what it means to provide an experience that matches the high level of craftsmanship and the unique conceptual and physical qualities of the objects being presented.

Together, Scheer and I established a general working premise for this exhibition that art jewelry is meant to be worn – touched. Artists were invited through a call for entries to put aside precious and fragile materials and instead to create designs using unexpected materials and construction techniques. Selected works needed to withstand physical handling by museum visitors over a period of several months, and, after the exhibition, works would become the foundation of the museum’s teaching collection. Working together, we reached a compromise by which visitors could directly experience the relational aspects of art jewelry – interaction between the object, wearer and the spectator.

The design of the installation needed to match the exhibition’s conceptual focus as well. Constructed with re-usable honeycomb cardboard, typically a packing material, we created an open, inviting, and non-hierarchical installation. Pegs on walls held neckpieces, while rings, brooches, and bracelets resided on cardboard ‘tabletops’ resting on sawhorses.

Using images submitted by participating artists, wallpapers were created to provide a backdrop for the exhibition and to help visitors by serving as a visual ‘cheat sheet’ for possible ways to wear the jewelry.

Extending individual experience further, an ‘art bar’ – fully stocked with materials, tools and books – was also available for visitors to try their own hand at making and wearing art jewelry.

Returning to the original image and argument that the shift in museums in recent years has been from the presentation of objects as markers of experience to experience itself, it seems clear to me that museum curators today have easily mastered the ontological types of presentations. Touching Warms the Art then swings the pendulum far, far into engagement. Now the opportunity remains to do something in between – or perhaps entirely new – that brings exhibition practices into a new middle ground where the socio-cultural contexts of making, wearing, protecting and displaying contemporary art jewelry may be better explored.

In conclusion, I would like to extend an idea proposed by Robert Storr from art museums to craft museums. (Storr 14) While Storr argues that ‘Showing is telling’, I believe that this exhibition demonstrates that ‘Showing is telling, but with art jewelry, touching might tell you more.’