Throughout history, jewelry has been social marker and amulet, used to enhance sexual allure, or for ceremony and ritual. Over time, jewelry-making evolved into a fine craft, largely created from precious metals and gemstones—which most still is. Nonetheless, a small but dedicated group of connoisseurs seeks a type of jewelry—termed “contemporary”—that, like painting and sculpture, is a vehicle for aesthetic expression. Its value can come from the exploration of ideas, new technology, and the incorporation of topical issues and even commentary. At times the work is conceptual, even provocative. Often it is very beautiful. Much of it stands out for the use of unexpected materials such as steel, wood, plastic, detritus, textiles, photographs, and even taxidermy.

Several museums specialize in jewelry from pre-history to the present day, but the inclusion of contemporary jewelry in jewelry museums only allows for limited comparison with other eras, locales, and/or formats. Placement at more broad-based institutions, within the context of painting, sculpture, and design, on the other hand, facilitates interdisciplinary analyses; and directors and curators of encyclopedic museums are thus becoming increasingly interested in contemporary jewelry. Maxwell L. Anderson, former Eugene McDermott Director of the Dallas Museum of Art, terms contemporary jewelry a “compelling genre within the broader contexts of painting and sculpture.”

The formidable, if small, group of collectors that has brought this field into the limelight has championed the makers, patronized galleries, funded ambitious exhibitions with erudite catalogs, and supported other publications. They have amassed sizable collections that, though each is different and highly personal (as jewelry would be), represent some of the most significant achievements in the field. Now, a significant number of these collectors is helping some of the world’s major museums build their holdings in the field.

This is, of course, a time-tested path for museums, to build collections from major gifts. But contemporary jewelry is a comparatively new area of inquiry and acquisition for museums—and unique for the modern collecting world in that it is so very personal, art that is best displayed when it is being worn. As such, jewelry is an intimate art, and so collectors often apply their own criteria when considering a piece. Thus, it’s worth understanding just who these collectors-turned-patrons are, since their private taste is shaping what the public will know about contemporary jewelry. Here is a look at nine such collections—and the people who created them.

The contributions of Helen Williams Drutt are inestimable. Her stated objective in pursuing the discipline is to “hold history,” not necessarily to build a collection. She has consistently sought superlative American and international work, not only for her own purposes but also to enlighten others, which she achieves through her lectures, writing, and more. In 1973 Drutt opened an eponymous gallery in her home city of Philadelphia, with contemporary jewelry a chief focus. Through the gallery’s outreach, her own scholarship, reverence for the artists, and curatorial acumen, Drutt spawned a following for contemporary jewelry that would otherwise be inconceivable.

In 2002 the Helen Drutt Gallery closed, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, subsequently accessioned through gift and purchase more than 800 of Drutt’s jewels and related drawings dating from 1960 to 2006. In 2007 the museum organized a traveling exhibition of approximately 300 objects from the collection, 275 of them pieces of jewelry. The accompanying book, Ornament as Art: Avant-Garde Jewelry from the Helen Williams Drutt Collection, along with Drutt’s 1995 book, Jewelry of Our Time: Art, Ornament and Obsession (co-written with the late Peter Dormer), have become standard texts on the subject. The late Peter C. Marzio, director of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, for 28 years, wrote in a stirring foreword to Ornament as Art: “The Drutt Collection attacks traditional academic, art historical categories. This subversive challenge forces us to abandon certain conventional modes of thought and to redefine ideas of sculpture, painting, decorative arts, and so forth.” Wishing to foster international understanding through the sharing of handmade objects, last year Drutt was responsible for the exhibition Gifts from America: 1948–2013—comprising 74 works given to the State Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, Russia, in celebration of the museum’s 250th anniversary. The works were donated by 43 artists and patrons, including Drutt, and featured works by 30 international jewelers. A noteworthy sign that this is a watershed moment is the evident desire by the Hermitage, one of the world’s oldest and largest museums of historical art and culture, to expand its commitment to collecting and exhibiting later twentieth- and twenty-first-century applied art, including jewelry.

Southern Californian Lois Boardman says that her friendship with Drutt led her “down the ruinous path of collecting.” Indebted nonetheless to Drutt for exposing her to the “fun and wonder” of pursuing contemporary jewelry when they first met in the early 1980s, Boardman amassed her own impressive collection of more than 300 pieces, much of which she and her husband Bob are donating to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. An exhibition of selections, Beyond Bling, opened in October 2016 and is accompanied by a catalog.

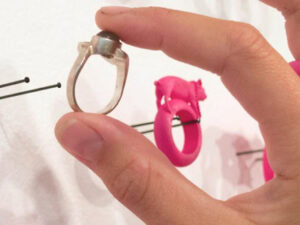

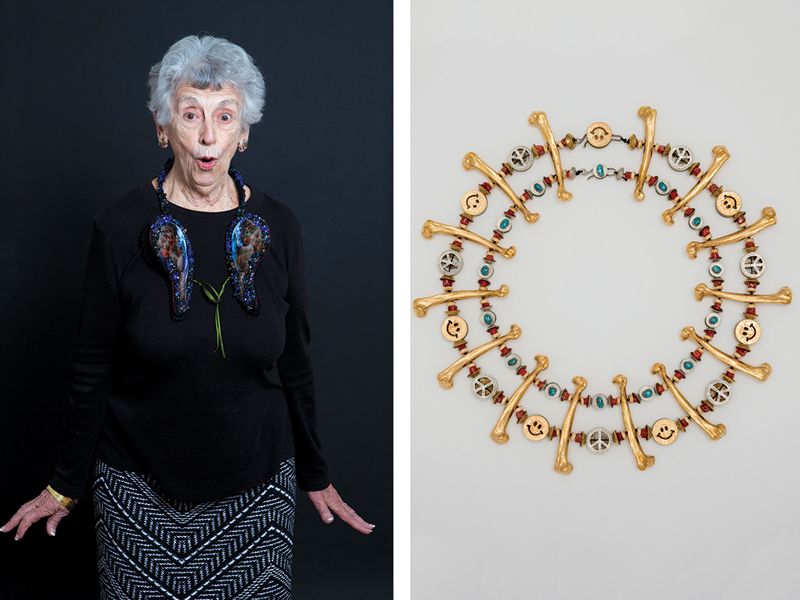

Contrary to what one might think, most jewelry collectors are not daunted by the provocative, humorous, or avant-garde—and Boardman is a prime example. In fact, she welcomes experimentation. Consider Washington state artist Nancy Worden’s gilded cast chicken-bone neckpiece Gilding the Past, or Virginia-based Susie Ganch’s Static Orbital Model #3, a headpiece in the form of a menorah. Boardman says that she has even worn German jeweler Georg Dobler’s necklace with a huge faceted amethyst centered between two hefty cast silver beetles, to Costco. Her strategy is to chart the aesthetic and technical development of each artist she believes is fundamental to the field by purchasing several of their works—although she admits her personal preference is for works in gold.

Former New York resident Donna Schneier, who also began collecting contemporary jewelry in the 1980s, chooses pieces for their concepts and actually wears very few of them. Unlike Boardman, she claims to have no “personal taste in jewelry,” selecting each work with a curator’s savvy and aiming to document the most authoritative objects by the most influential artists of the period. Schneier was initially attracted to “body adornment” being made in England and the Netherlands in the 1980s from atypical materials such as paper, fiber, rubber, tin, and plastic. She purchased several examples, which she displayed in the office from which she ran a business that imported conventional gold jewelry. In 1997 she donated a selection of these nonprecious works to the American Craft Museum (now the Museum of Arts and Design), which organized an exhibition and book around them titled Zero Karat. Then, in 2007 and 2013, Schneier donated some 132 examples of contemporary American and European jewelry to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In discussing the gift, Jane Adlin, former associate curator in the Met’s Department of Modern and Contemporary Art, commented: “I love jewelry … so … [I said] let’s see what we can do about strengthening that part of the [Met’s] collection … I look at contemporary jewelry as part of contemporary design.” In the spring of 2014 the museum organized an exhibition and accompanying catalog, Unique by Design, which spotlighted masterworks by Americans Thomas Gentille, Joyce J. Scott, and William Harper, and Germans Hermann Jünger, Otto Künzli, and Dorothea Prühl, among a panoply of other major international jewelers.

Comfort was a requisite for Daphne Farago when she considered a piece of jewelry for her collection. Farago began collecting in the late 1980s and possesses many stellar contemporary European works that illustrate the cross-fertilization between American and European jewelers during the later twentieth century, as well as mid-twentieth-century examples designed by international painters and sculptors. But her emphasis was on relating the story of American studio jewelry from its inception around 1940—with Alexander Calder’s powerfully wrought jewels of brass and silver—to its maturity at the turn of the twenty-first century. Born in South Africa, Farago made her primary home in Rhode Island, where she founded the Daphne Farago Wing for Contemporary Art at the Rhode Island School of Design Museum in 1993, a gallery that features exhibitions from the museum’s contemporary art collection. In addition, she has given more than 950 pieces of contemporary studio craft in a variety of mediums to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. These include more than 650 pieces of jewelry, many of which were featured in Jewelry by Artists: The Daphne Farago Collection, an exhibition that ran for nearly a year, from 2007 to 2008. A catalog, Jewelry by Artists in the Studio, 1940–2000: Selections from the Daphne Farago Collection, was published by the museum in 2010. Permanent loans and promised gifts from Farago continue to enter the MFA.

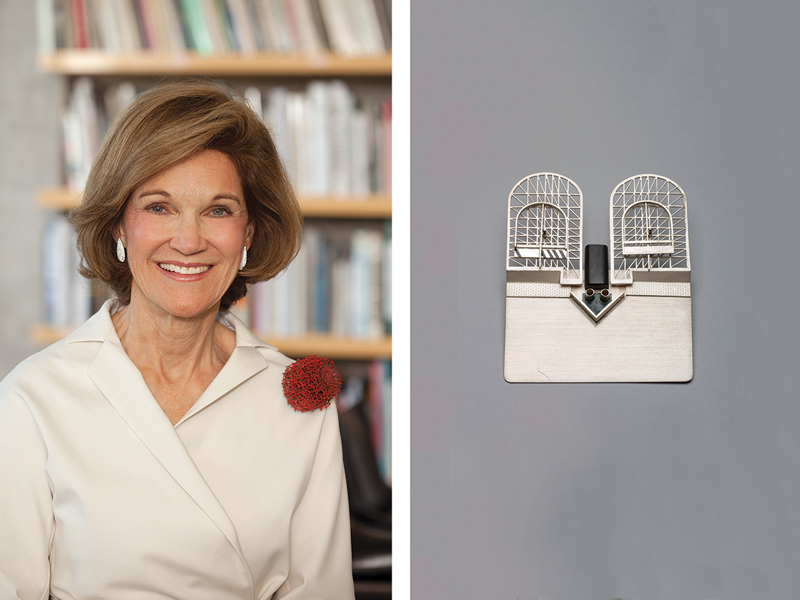

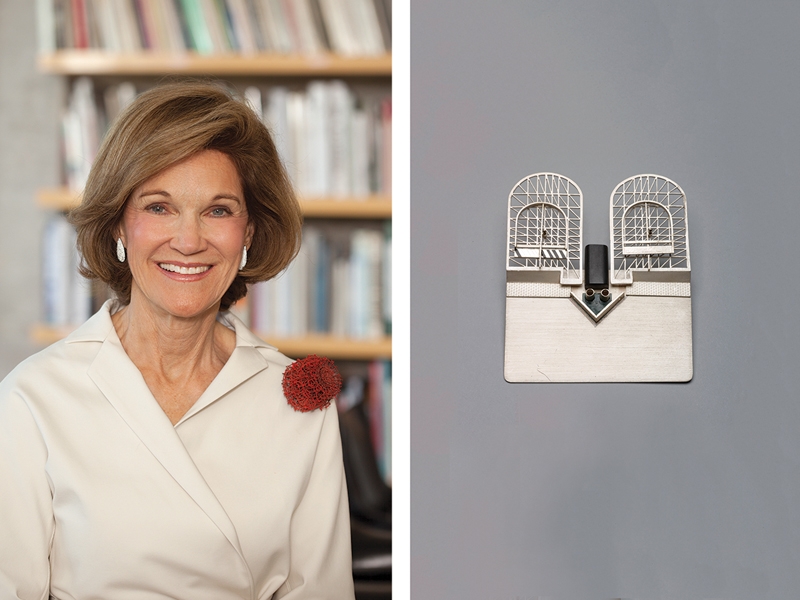

Deedie Potter Rose and her late husband, Edward W. Rose, have collected contemporary painting and sculpture, particularly from Latin America. That collection is earmarked for the Dallas Museum of Art as part of an effort to build a strong contemporary presence there. Deedie Rose became aware of contemporary jewelry accidentally in the early 1990s, when she happened upon images of two geometric stainless-steel brooches by Czech artist Eva Eisler in a magazine article. She pursued Eisler, and never looked back. Like contemporary art, contemporary jewelry, she feels, makes one “think in new ways.”

She has already given several works to the Dallas Museum, including a necklace of thin plastic tubing infused with steel jeweler’s sawblades and a brooch of densely layered watch hands and oxidized silver, both by American Sergey Jivetin. But Rose’s most generous contribution to date is the Rose-Asenbaum Collection, which came about through another chance encounter. In 2012, during a trip to Vienna, where she and her husband were seeking Wiener Werkstätte furniture, Rose was introduced to a spectacular collection of more than 700 pieces by international jewelry luminaries working from 1960 to the present—such as Slovak Anton Cepka, German Gerd Rothmann, Swiss Max Fröhlich, and Italian Francesco Pavan—that belonged to Austrian collector, consultant, and gallerist Inge Asenbaum. The following year Rose purchased Asenbaum’s collection for the Dallas Museum. As Kevin W. Tucker, former Margot B. Perot Senior Curator of Decorative Arts and Design there and now director of the Museum of the American Arts and Crafts Movement in Saint Petersburg, Florida, says, “The Rose-Asenbaum Collection provides special resonance with the DMA’s collection of modern and contemporary art as, freed from the usual constraints of design for practical function, these artists could and did explore conceptual issues, questioning not just style and materials but the very role of the objects they were creating.” A selection from the Rose-Asenbaum Collection is on view until the end of 2016 in Form/Unformed: Design from 1960 to the Present, an ongoing installation of iconic furniture and objects from DMA’s holdings.

The rich jewelry history of the Netherlands is a subject that Dutch art historian Marjan Unger has written and lectured extensively about, including Het Nederlandse sieraad in de 20ste eeuw (Dutch Jewelry in the 20th Century) in 2004. In celebration of her PhD, granted by Leiden University in 2010 for a thesis that addresses theoretical issues involving jewelry, she and her husband, Gerard, donated their collection of almost 500 pieces of Dutch twentieth- and twenty-first-century jewelry to the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. Although they concentrated on the period between 1930 and 1970, the Unger Collection extends the museum’s jewelry holdings to the present day, including outstanding examples by such contemporary masters as Paul Derrez, Robert Smit, and Beppe Kessler. Unger did not set out to amass such a group when she began purchasing modern Dutch jewelry in 1980. Rather she began acquiring through emotion and intellect, stating that her “professional relationship” with jewelry is characterized by “curiosity, complicity and the thrilling feeling of falling in love.”

The late Dutch art collector Ronald Kuipers was introduced to contemporary jewelry through fine art. After his death in 2014, his family donated his jewelry collection to CODA, a museum in Apeldoorn. Through this bequest, CODA added to its already exceptional collection of works by Dutch maker Evert Nijland and acquired significant pieces by Ruudt Peters, Felieke van der Leest, and Jantje Fleischhut, the Italian Marc Monzó, and Australian Helen Britton.

Since 2004 one of the world’s most impressive contemporary jewelry collections has been housed in the Danner Rotunda, a dedicated gallery supported by the Danner Foundation within the Neue Sammlung—The Design Museum in the Pinakothek der Moderne in Munich. The collection, consisting of a permanent loan from the Danner Foundation, as well as private donations, was inaugurated in 1995, when Serbian jeweler Peter Skubic gave 60 pieces—none made by him—to the museum in honor of his sixtieth birthday; the following year this core collection was buttressed by contributions from Austrian jeweler Sepp Schmölzer and German jewelers Marianne Schliwinski and her husband, Jürgen Eickhoff, owners of Munich’s Galerie Spektrum.

Peter Skubic also played a seminal role in the jewelry collection of Austrians Heidi and Karl Bollmann, a portion of which was exhibited at MAK, the Österreichisches Museum für angewandte Kunst/Gegenwartskunst (Austrian Museum of Applied Art/Contemporary Art) in early 2015. The Bollmann Collection of more than 1,000 objects began in 1972, when Karl Bollmann inherited some diamonds and commissioned Skubic to incorporate them into a jewel for Heidi. Bollmann believes that jewelry possesses “universal validity” in communicating thoughts and feelings. The Bollmanns regard the MAK exhibition and its splendid catalog, Jewellery 1970–2015: Bollmann Collection, as a “thank you” to the makers who have so enriched their lives.

Swiss nationals Sonja and Christian Graber recently donated an in-depth collection of jewelry and objects by countryman Bernhard Schobinger to the Kunsthaus Zug in Zug, Switzerland—along with photographs by Schobinger’s Zug-born wife, video artist and photographer Annelies Štrba, and paintings by Zurich’s Adrian Schiess. Known for his paradoxical jewelry made from precious materials and rubbish, Schobinger creates work that is simultaneously confrontational and mystical. Many of the works were published for the first time in the catalog that accompanied the exhibition Adrian Schiess, Bernhard Schobinger, Annelies Štrba: The Gift of the Graber Collections, held at the museum in the fall of 2015.

Thanks to an enthusiastic welcome from numerous museums and the gracious generosity of its growing collectorship, contemporary jewelry has a public platform. When asked about the importance of contemporary jewelry collections and the collectors who facilitate them, Glenn Adamson, Nanette L. Laitman Director at the Museum of Arts and Design, said: “One reason that we prize jewelry so highly at MAD is the way that it concentrates an artist’s ideas in such a condensed form. The opportunity to build a definitive collection of these objects is still more powerful, because it demonstrates the enormous range of the medium’s possibilities. And at the end of the day, museums and collectors are working together toward this shared goal, to communicate and preserve the work of artists we respect so highly.”

Reproduced with kind permission from Modern Magazine and the author.

INDEX IMAGE: Sam Kramer and Carol Kramer, Lovers, 1949, brooch, silver, turquoise, garnet, 114 x 83 x 25 mm, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Daphne Farago Collection, photo: Museum of Fine Arts Boston

La joyería contemporánea se pronuncia

Por Tony Greenbaum

Foto 1. A la izquierda Helen Williams Drutt con aretes collar, broche, brazalete y anillo de su colección privada. Foto: Andrea Baldeck. A la derecha: Gijs Bakker. Broche “Waterman “1990 PVC, fotografía y diamantes 152 x 67 x6mm Museo de Bellas Artes de Houston, Colección Drutt. Foto; Artis/ARS NY.

A través de la historia, la joyería ha sido el indicador social y un amuleto usado para realzar el encanto sexual, para la ceremonia o para el ritual. Con el tiempo, la fabricación de joyería evolucionó en artesanía fina, en gran parte creada a partir de metales y piedras preciosas, tradición que aún se mantiene. Sin embargo, un grupo pequeño pero dedicado de conocedores busca un tipo de joyería llamada “contemporánea”, que, como la pintura y la escultura, es un vehículo para la expresión estética. Su valor puede provenir de la exploración de ideas, las nuevas tecnologías, y la incorporación de temas de actualidad e incluso comentarios. A veces el trabajo es conceptual, incluso provocativo y a menudo es muy hermoso. Gran parte de ella se destaca por el uso de materiales inesperados como el acero, madera, plástico, debris, textiles, fotografías, e incluso taxidermia.

Varios museos se especializan en la joyería desde la prehistoria hasta la actualidad pero, la inclusión de joyas contemporáneas en los museos de joyería sólo permite una comparación limitada con otras eras, lugares y / o formatos. El ubicarla en instituciones más amplias, dentro del contexto de la pintura, la escultura y el diseño, facilita los análisis interdisciplinarios; y los directores y curadores de los museos enciclopédicos están cada vez más interesados en la joyería contemporánea. Maxwell L. Anderson, ex director de Eugene McDermott en el Museo de Arte de Dallas, califica a la joyería contemporánea como “un género irresistible dentro de los contextos más amplios de la pintura y la escultura”.

El formidable, aunque pequeño, grupo de coleccionistas que ha puesto este campo en el centro de atención ha abogado por los creadores, patrocinado galerías, financiado exposiciones ambiciosas con catálogos eruditos, y apoyado otras publicaciones. Han acumulado colecciones considerables que, aunque cada una es diferente y muy personal (como sería la joyería), representan algunos de los logros más significativos en el campo. Ahora, un número significativo de estos coleccionistas está ayudando a algunos de los museos más importantes del mundo a construir sus colecciones en este campo.

Construir colecciones a base de regalos importantes constituye un camino ya transitado por los museos. Pero la joyería contemporánea es un área comparativamente nueva de investigación y adquisición para los museos -y única para el mundo de la colección moderna ya que la joyería es tan personal, que es un arte que se muestra mejor cuando está en uso. Y es así como la joyería es un arte íntimo, por lo que los coleccionistas a menudo aplican sus propios criterios al considerar una pieza. Por lo tanto, vale la pena entender quiénes son estos coleccionistas convertidos en clientes, ya que su gusto personal está configurando lo que el público sabrá acerca de la joyería contemporánea. Aquí hay una breve mirada a nueve colecciones de este tipo y las personas que las crearon.

Foto 2: A la izquierda Pieza de Stanley Lechtzin “Torque 22-D” gargantilla 1971. Plata Sterling y resina de poliéster 229x241x64mm. Museo de Bellas Artes de Houston Colección Drutt. A la derecha Pieza de David Watking “Bisagra Bucle” gargantilla con 3 barra 1974. Acrílico y Plata Sterling, 26.7 x 13.3x 1.3

Las contribuciones de Helen Williams Drutt son inestimables. Su objetivo declarado al perseguir la disciplina es “mantener la historia”, no necesariamente construir una colección. Ella siempre ha buscado trabajos superlativos americanos e internacionales, no sólo para sus propios propósitos, sino también para orientar a otros, lo que logra a través de sus conferencias, escritos y más. En 1973 Drutt abrió una galería epónima en su ciudad natal, Filadelfia, cuyo foco principal eran las joyas contemporáneas. A través de la divulgación de la galería, su propio conocimiento, la reverencia de los artistas, y la perspicacia de su curaduría, Drutt logró un gran número de seguidores de la joyería contemporánea que de otra manera sería inconcebible.

En 2002 se cerró la Galería Helen Drutt y el Museo de Bellas Artes de Houston posteriormente adquirió más de 800 joyas de su pertenencia así como dibujos relacionados que datan de 1960 a 2006. En 2007 el museo organizó una exposición itinerante de aproximadamente 300 objetos, de los cuales 275 eran piezas de joyería. El libro que acompañaba, Ornament as Art: Avant-Garde Jewelry from the Helen Williams Drutt Collection, (Ornamento como Arte: Joyería de vanguardia de la colección de Helen Williams Drutt) junto con el libro de 1995 de Drutt, Jewelry of Our Time: Art, Ornament and Obsession (Joyería de nuestro tiempo: Arte, Ornamento y Obsesión), co-escrito con el fallecido Dormer, se han convertido en textos estándar sobre el tema. El difunto Peter C. Marzio, director del Museo de Bellas Artes de Houston, durante 28 años, escribió en un emocionante prefacio a Ornament as Art: “La Colección Drutt ataca a las categorías académicas tradicionales e históricas del arte. Este desafío subversivo nos obliga a abandonar ciertas formas convencionales de pensamiento y a redefinir las ideas de la escultura, la pintura, las artes decorativas, etcétera“. Deseando fomentar la comprensión internacional mediante el intercambio de objetos hechos a mano, el año pasado Drutt fue responsable de la exposición Gifts from America: 1948–2013, (Regalos De América: 1948-2013) exposición que abarcó 74 obras entregadas al Museo Estatal del Hermitage en San Petersburgo, Rusia, en conmemoración del 250 aniversario del museo. Las obras fueron donadas por 43 artistas y mecenas, entre ellos Drutt, y contó con obras de 30 joyeros internacionales. Un signo notable de que este es un momento decisivo, es el deseo evidente del Hermitage, uno de los museos de arte y cultura históricos más antiguos y más grandes del mundo, de ampliar su compromiso de recolectar y exhibir arte aplicado en los siglos veinte y veintiuno, incluyendo joyas.

Foto 3: A la izquierda, Lois Boardman con collar titulado “Gane mis alas”, Pieza de alas de perico disecadas del artista Afke Golsteijn 2013, foto de Miriam Künzli/Art Aurea. Derecha: Nancy Worden Guilding the Past cobre con baño de oro y monedas de plata, hueso, coral, turquesa, bronce y algodón. 438x451x19mm. LACMA regalo de Lois y Bob Boardman. Foto: Museums Associates/LACMA

La californiana Lois Boardman dice que su amistad con Drutt la condujo por ¨el ruinoso camino de coleccionar”. Sin embargo agradece a Drutt haberle enseñado la “diversión y maravilla” de perseguir la joyería contemporánea cuando se conocieron a inicios de la década de 1980. Boardman amasó su impresionante colección de más de 300 piezas, muchas de las cuales ella y su esposo Bob, están donando al Museo de Arte del Condado de Los Ángeles. Una exposición de selecciones, Beyond Bling (Más allá del brillo), se inauguró en octubre de 2016 y está acompañada por un catálogo.

Por el contrario a lo que uno podría pensar, la mayoría de los coleccionistas de joyas les atrae la provocación, el humor o la vanguardia, y Boardman es un excelente ejemplo. De hecho, ella le agrada la experimentación. Prueba de ello lo constituye el collar de huesos de pollo dorado mediante el proceso de fundición de la artista del estado de Washington Nancy Worden, titulado Gilding the Past o la pieza del artista de Virgina Susie Ganch, Static Orbital Model #3, una pieza para la cabeza en forma de una menorah. Boardman dice que incluso ha llevado piezas que van desde el collar con una gran amatista facetada centrada entre dos escarabajos de plata del joyero alemán Georg Dobler, hasta joyas de Costco. Su estrategia es trazar el desarrollo estético y técnico de cada artista que ella cree es fundamental para el campo comprando varias de sus obras, aunque admite que su preferencia personal es por las obras en oro.

Foto 4: Caroline Broadhead (1978) collar de Plata, Algodón y Nylon. 203x203x10mm. Museum of Art and Design , New York donación de Donna Schneier. Foto John Bidelow Taylor

La ex residente de Nueva York Donna Schneier, quien también comenzó a coleccionar joyas contemporáneas en la década de 1980, elige las piezas por sus conceptos y en realidad viste muy pocas de ellas. A diferencia de Boardman, afirma que no tiene “gusto personal en la joyería”, seleccionando cada trabajo con la habilidad de un curador y con el objetivo de documentar los objetos más autoritativos de los artistas más influyentes de la época. Schneier se sintió atraída inicialmente por el “adorno corporal” hecho en Inglaterra y Holanda en la década de 1980 a partir de materiales atípicos como papel, fibra, caucho, estaño y plástico. Ella compró varios ejemplos, los cuales exhibió en la oficina de un negocio de importación de joyería convencional de oro que dirigía. En 1997 donó una selección de estas obras de materiales no preciosos al American Craft Museum (hoy Museo de Artes y Diseño), el cual organizó una exposición y un libro alrededor de estas titulado Zero Karat. Luego, en 2007 y 2013, Schneier donó unos 132 ejemplares de joyas americanas y europeas contemporáneas al Metropolitan Museum of Art de New York. Al comentar el regalo, Jane Adlin, antigua curadora asociada del Departamento de Arte Moderno y Contemporáneo del Metropolitan, comentó: “Me encanta la joyería … así que … [Dije] veamos qué podemos hacer para fortalecer esa parte del [Metropolitan]…veo la joyería contemporánea como parte del diseño contemporáneo”. En la primavera de 2014 el museo organizó una exposición y un catálogo para acompañarla, Unique by Design, que destacó las obras maestras de los estadounidenses Thomas Gentille, Joyce J. Scott y William Harper, y los alemanes Hermann Jünger, Otto Künzli, y Dorothea Prühl, entre un conjunto de otros grandes joyeros internacionales.

Foto 5.Bruno Martinazzi, “Goldfinger” 1969 Brazalete Cuff de oro amarillo de 20 quilates y oro blanco de 18 quilates, ancho 65mm. Museo de Bellas Arte de Boston Colección Farago. Foto: Museo de Bellas Arte de Boston

La comodidad era un requisito para Daphne Farago cuando consideraba una pieza de joyería para su colección. Farago comenzó a coleccionar a finales de los años 1980 y posee muchas obras europeas contemporáneas estelares que ilustran la fertilización cruzada entre los joyeros americanos y europeos de finales del siglo XX, así como ejemplos de mediados del siglo XX diseñados por pintores y escultores internacionales. Pero su énfasis estaba en relacionar la historia de la joyería americana de estudio desde sus inicios alrededor de 1940 -con las poderosas joyas de cobre y plata de Alexander Calder – hasta su madurez a principios del siglo XXI. Nacida en Sur Africa, Farago hizo su residencia principal en Rhode Island, donde fundó el Daphne Farago Wing for Contemporary Art en el museo del diseño del museo de Rhode Island en 1993, una galería que ofrece exposiciones de la colección del arte contemporáneo del museo. Además, ha entregado más de 950 piezas de arte de estudio contemporáneo en una variedad de medios al Museo de Bellas Artes en Boston. Estos incluyen más de 650 piezas de joyería, muchas de las cuales se incluyeron en la exposición Jewelry by Artists: The Daphne Farago Collection una exposición que se desarrolló durante casi un año, de 2007 a 2008. Un catálogo, Jewelry by Artists in the Studio, 1940–2000: Selections from the Daphne Farago Collection, fue publicado por el museo en 2010. Los préstamos permanentes y las donaciones prometidas de Farago continúan incorporándose en el Museo de Bellas Artes de Boston.

Deedie Potter Rose y su difunto esposo, Edward W. Rose, han coleccionado pintura y escultura contemporánea, particularmente de América Latina. Esa colección está destinada al Museo de Arte de Dallas como parte de un esfuerzo para construir una fuerte presencia contemporánea en ese lugar. Deedie Rose descubre la joyería contemporánea accidentalmente a principios de los 1990, cuando encontró imágenes de dos broches geométricos de acero inoxidable de la artista checa Eva Eisler en un artículo de la revista. Ella persiguió a Eisler, y nunca volvió atrás. Comenta que al igual que el arte contemporáneo, la joyería contemporánea, te hace “pensar de maneras distintas”.

Deedie Potter Rose ha donado varios trabajos al Museo de Dallas, incluyendo un collar de tubo de plástico delgado con sierras de joyero de acero imbuidas y un broche de manecillas de reloj de capas densas y plata oxidada, ambos realizados por el estadounidense Sergey Jivetin. Pero la contribución más generosa de Rose hasta la fecha es la Colección Rose-Asenbaum, que surgió a través de otro encuentro casual. En 2012, durante un viaje a Viena, donde ella y su marido estaban buscando muebles del Wiener Werkstätte, Rose fue introducida a una espectacular colección de más de 700 piezas de joyería internacional de luminarias que trabajan desde 1960 hasta la actualidad como el eslovaco Anton Cepka, el alemán Gerd Rothmann, el suizo Max Fröhlich y el italiano Francesco Pavan, que pertenecían al coleccionista austríaco, consultor y galerista Inge Asenbaum. Al año siguiente, Rose compró la colección de Asenbaum para el Museo de Dallas. Como dice Kevin W. Tucker, ex curador principal de Artes Decorativas y Diseño del Museo de Arte Margot B. Perot y ahora director del Museo del Movimiento Americano de Artes y Oficios en San Petersburgo, Florida, “La Colección Rose-Asenbaum ofrece resonancia especial con la colección de arte moderno y contemporáneo del Museo de Arte de Dallas, libre de las limitaciones habituales del diseño para la función práctica, estos artistas pudieron explorar cuestiones conceptuales, cuestionando no sólo el estilo y los materiales, sino el papel mismo de los objetos que estaban creando“. Una selección de piezas de la Colección Rose-Asenbaum estuvo expuesta hasta finales de 2016 en Form/Unformed: Design from 1960 to the Present, una instalación de mobiliario icónico y objetos de las propiedad del Museo de Artes de Dallas.

Foto 6: A la izquierda Marjan Unger con collar de Robert Smit “Sketch for Sleeping Beauty II” 1990. Foto de Michaël Ferron Rijksmeseum , Ámsterdam de la colección Unger. A la derecha “Cara” 1994 de Paul Derrez , Plástico aluminio y caucho 70x60x25mm Rijksmeseum , Ámsterdam de la colección Unger. Foto: Rijksmeseum

La rica historia de la joyería de los Países Bajos es un tema sobre el que la historiadora de arte holandesa Marjan Unger ha escrito y ha dado conferencias, incluyendo Het Nederlandse sieraad in de 20ste eeuw (Joyería holandesa en el siglo XX) en 2004. En la celebración de su PhD, concedido por La Universidad de Leiden en 2010 para una tesis que aborda cuestiones teóricas relacionadas con la joyería, ella y su esposo, Gerard, donaron su colección de casi 500 piezas de joyas holandesas del siglo XX y XXI al Rijksmuseum de Ámsterdam. Aunque se concentraron en el período comprendido entre 1930 y 1970, la Colección Unger extiende las posesiones de joyería del museo hasta nuestros días, incluyendo ejemplos destacados de maestros contemporáneos como Paul Derrez, Robert Smit y Beppe Kessler. Unger no se dispuso a acumular tal grupo cuando empezó a comprar joyería holandesa moderna en 1980. En su lugar, empezó a adquirir a través de la emoción y el intelecto, afirmando que su “relación profesional” con la joyería se caracteriza por “curiosidad, complicidad y el emocionante sentimiento de enamorarse.”

Foto 7: Felieke Van Der Leest “Incognitos Anónimos” 2011. Collar y objeto plata cuentas de vidrio tejido, cuero, plástico . Ancho: 168mm, Alto: 50mm. CODA Apeldoorn. Donación de Ronald Kuipers. Foto: Nasjonalmuseet/Frode Larsen

El coleccionista de arte holandés Ronald Kuipers fue introducido a la joyería contemporánea a través de arte. Después de su muerte en 2014, su familia donó su colección de joyas a CODA, un museo en Apeldoorn, Holanda. A través de este legado, CODA añadió a su ya excepcional colección de obras del fabricante holandés Evert Nijland y adquirió piezas significativas de Ruudt Peters, Felieke van der Leest y Jantje Fleischhut, del italiano Marc Monzó y de la australiana Helen Britton.

Desde 2004, una de las colecciones de joyas contemporáneas más impresionantes del mundo ha sido alojada en la Danner Rotunda, una galería dedicada a la joyería con el apoyo de la Fundación Danner dentro del Neue Sammlung-El Museo del Diseño en la Pinakothek der Moderne en Munich. La colección, consistente en un préstamo permanente de la Fundación Danner, así como donaciones privadas, fue inaugurada en 1995, cuando el joyero serbio Peter Skubic entregó 60 piezas – ninguna hecha por él – al museo en honor a su sexagésimo cumpleaños; al año siguiente, esta colección central fue reforzada por las aportaciones del joyero austríaco Sepp Schmölzer y de los joyeros alemanes Marianne Schliwinski y su marido, Jürgen Eickhoff, propietarios de la Galerie Spektrum de Munich.

Foto 8: Otto Künzli “Big American” Collar de 1968 de Acero inoxidable. Neue Sammlung

Peter Skubic también desempeñó un papel fundamental en la colección de joyería de los austríacos Heidi y Karl Bollmann, una parte de la cual fue expuesta en MAK, el Österreichisches Museum für angewandte Kunst / Gegenwartskunst (Museo Austriaco de Arte Aplicado / Arte Contemporáneo) a principios de 2015. La colección Bollmann de más de 1.000 objetos comenzó en 1972, cuando Karl Bollmann heredó algunos diamantes y encargó Skubic para incorporarlos en una joya para Heidi Bollman. Bollmann cree que la joyería posee “validez universal” en la comunicación de pensamientos y sentimientos. Los Bollmann consideran la exposición MAK y su espléndido catálogo, Joyería 1970-2015: Colección Bollmann, como un “agradecimiento” a los creadores que han enriquecido sus vidas.

Los suizos Sonja y Christian Graber donaron recientemente una colección que aborda en profundidad las joyas y objetos de su compatriota Bernhard Schobinger a la Kunsthaus Zug in Zug, Suiza, junto con fotografías de la esposa, artista de video y fotógrafo Annelies Štrba de Schobinger y pinturas de Adrian Schiess de Zúrich. Conocido por su joyería paradójica hecha de materiales preciosos y basura, Schobinger crea trabajos que son simultáneamente confrontativos y místicos Muchas de las obras fueron publicadas por primera vez en el catálogo que acompañó la exposición Adrian Schiess, Bernhard Schobinger, Annelies Štrba: El regalo de las colecciones de Graber, que se celebró en el museo en el otoño de 2015.

Gracias a la acogida entusiasta de numerosos museos y la generosidad de su creciente coleccionismo, la joyería contemporánea tiene una plataforma pública. Cuando se les preguntó sobre la importancia de las colecciones de joyas contemporáneas y los coleccionistas que las facilitan, Glenn Adamson, director de Nanette L. Laitman en el Museo de Artes y Diseño, dijo: “Una de las razones por las que premiamos tanto a la joyería en MAD es por la manera en que se concentran las ideas de un artista en una forma tan condensada. La oportunidad de construir una colección definitiva de estos objetos es aún más poderosa, porque demuestra la enorme gama de posibilidades del medio. Y al final del día, los museos y coleccionistas están trabajando juntos para alcanzar este objetivo compartido, para comunicar y preservar el trabajo de los artistas que respetamos enormemente“.

Foto 9: A la izquierda Habicht pieza en madera de olmo de Dorotea Prühl 2006. A la derecha Karl Bollman con Broche Grafiti de Annamaria Zanella, 1990-1999

Reproducido con el permiso de la Revista Moderne y la autora

Toni Greenbaum es una historiadora del arte que se especializa en joyería y metalistería de los siglos XX y XXI. Ha escrito innumerables artículos de revistas, capítulos de libros y catálogos de exposiciones, y es autor de Messengers of Modernism: American Studio Jewelry, 1940-1960. Ella enseña internacionalmente y enseña Teoría y Crítica de Joyería Contemporánea en el Pratt Institute en Brooklyn, Nueva York.

Translated from English by Andreína Rodriquez, with support from Barbara Magaña and Marina Acosta.