Like many of Anni Albers’s woven pieces, the 1941 hardware necklace series she made with former student Alex Reed was informed by her travels throughout South America. Reflecting on the incorporation of natural materials in ancient jewelry discovered in a tomb near Oaxaca, Mexico, Albers explained, “The art of Monte Alban had given us the freedom to see things detached from their use, as pure materials, worth being turned into precious objects.”[1] By separating form from function, Albers and Reed created innovative designs using common objects.

Composed of materials found in five and dime stores, the drain and paperclip necklace features a large, circular sink strainer hung by an industrial-looking chain, with paperclips hung decoratively from the pendant.

If Albers and Reed were able to separate the found objects from their intended use, the general public had a harder time making that same distinction. The hardware-store origins were highlighted in newspaper articles and reviews, such as this sarcastic response to The Museum of Modern Art’s 1946 exhibition, Modern Handmade Jewelry, published by Robert C. Ruark in Philadelphia’s The Evening Bulletin:

“My love is like a red, red, rose, and if she is a good girl, I will deck her with nuts and bolts, hang a tired tin can around her neck and ring her wrists with paper clips. And if she hollers “hardware!” I will kick her pearly little teeth out, because friends, this is art, high art.”[2]

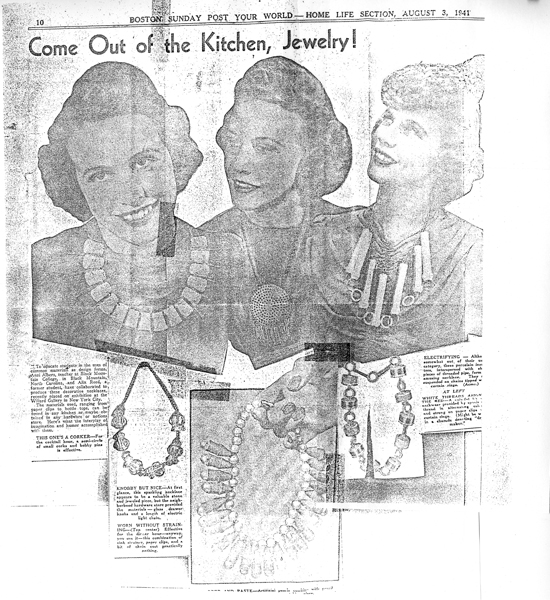

Ruark’s strong reaction to the hardware necklaces reveals a familiar narrative about how jewelry can and has functioned—as a gift whose inherent value lies in its material worth and/or a symbol of power or dominance over the wearer/receiver. His reactionary point of view was not, however, shared by all: The art world condemned Ruark for not recognizing the “advanced thinking” of Albers and Reed,[3] an innovative approach to jewelry that was appreciated in an earlier and unexpected location, the Boston Sunday Post.

In 1941, its Home Life section showcased the hardware necklaces worn by models with perfectly rolled hair, flawless complexions, and pristine smiles. The caption reads:

“WORN WITHOUT STRAINING – Effective for the dinner hours—anyway you use it—this combination of sink strainers, paper clips, and a bit of chain costs practically nothing!”[4]

[1] Anni Albers, speech to the Black Mountain Women’s Club on March 25, 1942.