- By exploring forms and color and using base materials, Annamaria Zanella radically innovated the language of jewelry

- An expert gold- and silversmith, she also excelled at the techniques of enameling and niello

- She won the prestigious Herbert Hofmann prize twice, in 1997 and 2006

- The Italian maker studied under Francesco Pavan, Graziano Visintin, and Renzo Pasquale, who later became her life partner

On November 8, 2022, the jewelry world lost a magically gifted artist who changed the shape of contemporary jewelry. Annamaria Zanella was an exceptional individual whose spirit and courage were inspirational.

A native of Padua, Italy, Annamaria trained at the prestigious Istituto Statale d’Arte Pietro Selvatico there, under Francesco Pavan. She then studied sculpture at the Academy of Fine Arts, Venice, graduating in 1992. Renzo Pasquale, another teacher at the Istituto who later became her partner in life, was a devoted admirer and supporter of her work. Annamaria and I called him “Il Salvatore” because he was her steadfast protector.

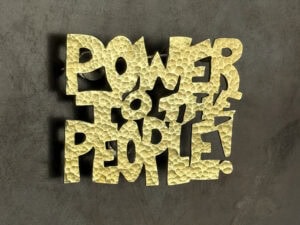

Annamaria revolutionized the classical jewelry traditions in Italy by introducing shocking new figurations using unexpected juxtapositions of materials and colors. While embracing the aesthetics and masterful workmanship for which the Padua School is renowned, she combined precious metals with humble materials inspired by the masters of Arte Povera, a movement in post-World-War-II Italy. She made stunning jewelry featuring salvaged rusty iron, wire mesh, broken glass, or bits of cork and scratched enamel, thus enriching the language of contemporary jewelry.

The stories behind a material she used were important for Annamaria. For example, after she suffered an automobile accident, a shard of glass from the broken windshield became a striking ring featured in an exhibition I curated; the Champagne bottle wire in a necklace was a reminder of friendship and celebration; her use of dyed metal to create malleable pleats in her jewelry reflected her love of elegant Fortuny fabric.

In her hands, simple cubes of lightweight cork became a sensuous necklace of brilliant gold facets against deep blue lapis lazuli, which was her signature color. Her work frequently emphasized her enduring love for the deep blue ceiling and frescos by Giotto in the Arena Chapel (also known as the Scrovegni Chapel) in Padua, which she greatly enjoyed taking visitors to see.

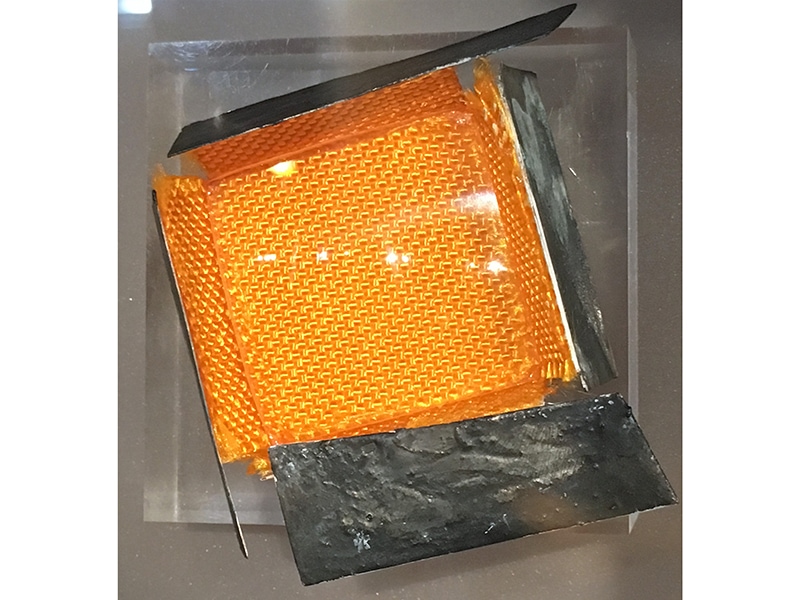

Annamaria had multiple sclerosis, a long and debilitating illness that confined her to a wheelchair when she traveled. But she was indefatigable, and I have fond memories of joining her in Venice for her exhibition at the Fortuny Museum, and on many occasions in Munich for the annual Schmuck jewelry week celebrations, where she was twice awarded the prestigious Herbert Hofmann Prize. Despite the protests of her friends, she even ventured to Lago Iseo, a lake in the Lombardy region of Italy, to experience the wonder of Christo’s and Jeanne Claude’s orange Floating Piers, made of a textile Zanella later used for some of her own works. In 2019, the Padua Municipality honored her with the Seal of the City in conjunction with an extensive exhibition of hundreds of her works at the Oratory of San Rocco.

Zanella garnered international recognition for her works, which are included in numerous permanent collections, including the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Palais du Louvre, Paris; the Victoria and Albert Museum, London; Le Gallerie degli Uffizi, Palazzo Pitti, Florence; National Museums Scotland, Glasgow; Kunstgewerbemuseum, Berlin; Die Neue Sammlung (The Design Museum), Munich; Schmuckmuseum Pforzheim; Swiss National Museum, Zurich; and the Cooper Hewitt Museum and the Museum of Arts and Design, both in New York. Her splendid monograph, La Poesia de la Matiera (The Poetry of Matter), published in 2018 by Arnoldsche Art Publishers, in Stuttgart, bears a lasting testimony to her outstanding talent and influence on contemporary jewelry, demonstrating why she became one of its most admired creators.

On a personal level, Zanella was a profound humanitarian. She greeted everyone with a welcoming smile and what I perceived to be a deep look into a person’s soul. She was empathetic with the fragile and those to be defended. Of the many qualities that gained her international fame, first and foremost for me was her unique ability to imbue her pieces with extraordinary strength and her love for life and art.

FURTHER READING

- Roberta Bernabei interviewed Zanella for AJF in 2017. Read their conversation here.

- Watch Zanella in AJF Live—Gallery Loupe: One World/40 Artists Respond to COVID-19. Zanella and her husband, Renzo Pasquale, are introduced at the 44-minute mark.