Reigning Men: Fashion in Menswear, 1715–2015

April 10–August 21, 2016

Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA)

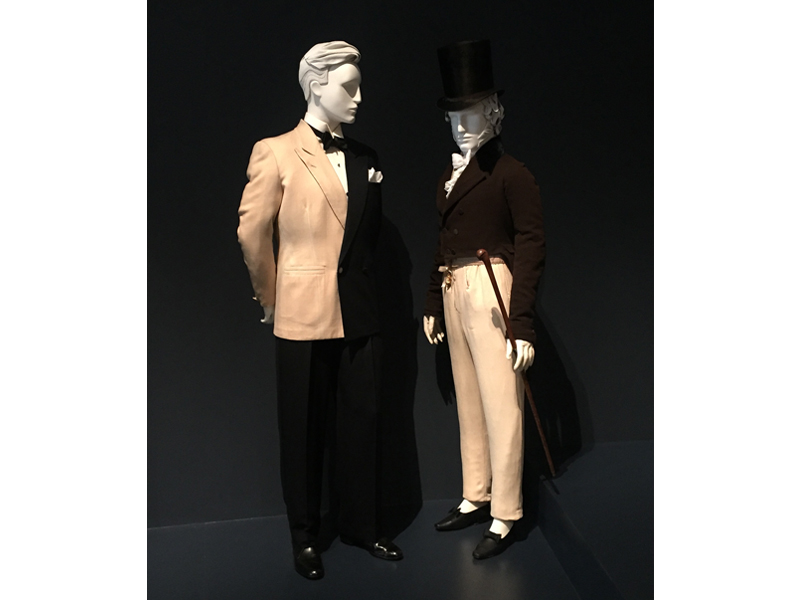

Whether we consciously adopt a particular style or fashion, or thoughtlessly throw on clothes, our identity is communicated through our appearance. This extends to the details: the angle a hat is positioned, whether or not a shirt is tucked in, five bracelets or just one. Our style can be a signifier of our personalities, interests, and economic situation. And so when planning a museum exhibition on clothing, curators must consider the nuances of style and find ways to incorporate this visually onto a static mannequin. Jewelry, and other accessories, can complete a particular look and convey a depth of ideas.

In LACMA’s current exhibition, Reigning Men: Fashion in Menswear, 1715–2015, the particulars of each look have been researched and implemented with care by a team of curators and installation specialists. As a newcomer to this particular branch of the museum world, I had the good fortune of observing as curators debated the proper break in the leg of trousers, the correct-sized knot in a cravat, or the proper placement of a shoe buckle. Historical accuracy is paramount in creating an exhibition focused on dress, but the styling details and accessories—a silk nosegay, a pocket watch, or a lace cravat—do more than just place a look in a specific decade. The way the clothes and accessories are interpreted onto the mannequin can reflect an attitude or spirit of a time, highlighting the larger social issues that are inherent to dress and ultimately resulting in a more exciting, engaging presentation.

With over 130 mannequins included in the show, the team at LACMA sourced a variety of nonaccessioned or prop items to complete the looks. These included custom wigs, shoes, shoe buckles, lace cuffs, shirt collars, and of course jewelry. The curators made every effort to use period-appropriate items, but in some cases it was impossible to find extant objects through dealers, auction houses, or in other museum collections. Items such as shoes or shirt collars rarely survive, so the curatorial staff commissioned custom pieces to complete the appropriate silhouettes.

In other instances, such as with the early jewelry pieces, the curators chose to use reproductions, not because they didn’t have such objects in their collection, but rather because they couldn’t display valuable 18th- and 19th-century pieces on a mannequin without the security of a case.

Although the pieces displayed are not museum objects, the curators relied on paintings, drawings, prints, fashion plates, sculpture, relevant contemporary writing, and photography from each time period to inform the designs of the jewelry. Being in Los Angeles, the curators took advantage of their proximity to Hollywood and commissioned work from the preeminent jeweler and metalworker to the silver screen, Maggie Schpak. As owner and operator of the Metal Arts Studio in Glendale, California, Schpak has created some of the most iconic metal jewelry and accessories seen in film and television.

Schpak’s work uses the symbolic nature of jewelry to move plotlines, invoke past historical periods, and ultimately to enrich characters. She began her career in the ladies wardrobe department of Western Costume, a full-service costume shop catering to the film and television world. Established in 1912, Western Costume continues to provide designers and costumers with costume rentals, custom tailoring and dressmaking, a millinery shop, and a research library. In the 1960s, Schpak and her ex-husband, a fellow artist named Tom Browne, transferred to the metal shop, maintaining the costume house’s holdings and fabricating specialized pieces. After over 10 years there, they made a decision to break away from Western and start their own metal shop. Despite their quick success, Schpak claims that they had no real knowledge of the craft and were simply “young and dumb.”

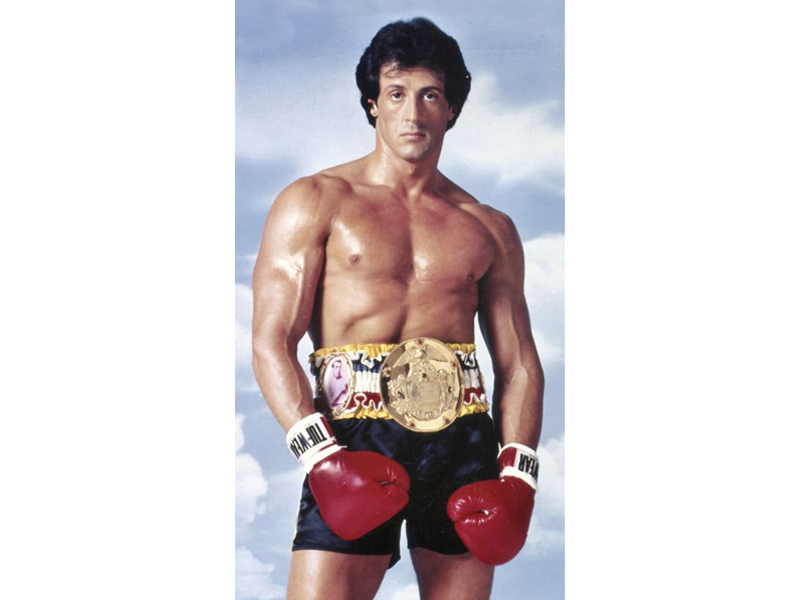

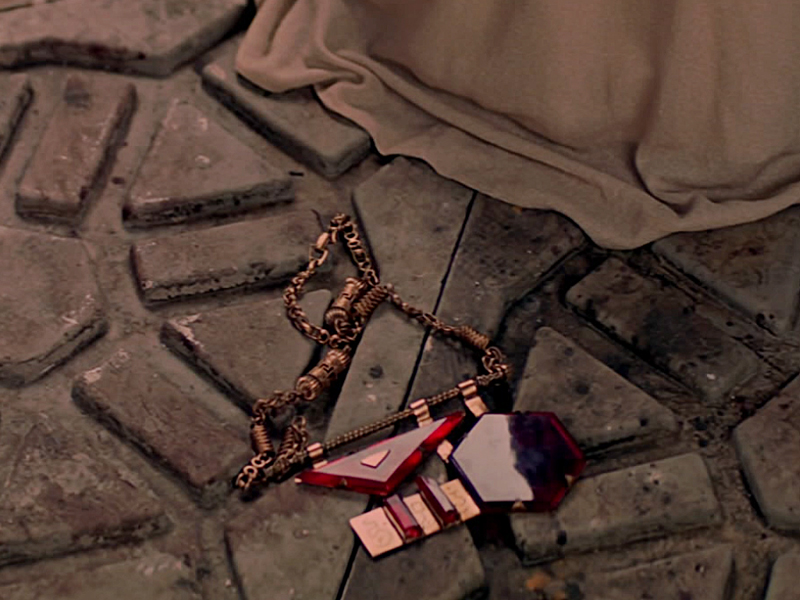

Schpak has owned and operated the Studio Art Metal Shop for more than four decades. In that time, her varied body of work reflects some of the changing cultural interests and styles portrayed in television, film, and popular culture. In the 1980s, Schpak’s projects have the excessive, outsized quality one associates with the Reagan era. Her pieces function as a centerpiece, meant to attract attention: from the armor worn in Masters of the Universe to the championship belt in the Rocky films to the accessories worn by Michael Jackson during his 1987 Bad tour. The continuing interest in science fiction has provided Schpak with steady work. She and her former husband and business partner collaborated with costume designer Bob Fletcher in designing and fabricating jewelry and insignias for the Star Trek films. Schpak, favoring the pieces meant for Vulcans over those for Klingons, drew inspiration from Art Deco styles to create a retro vision of the future.

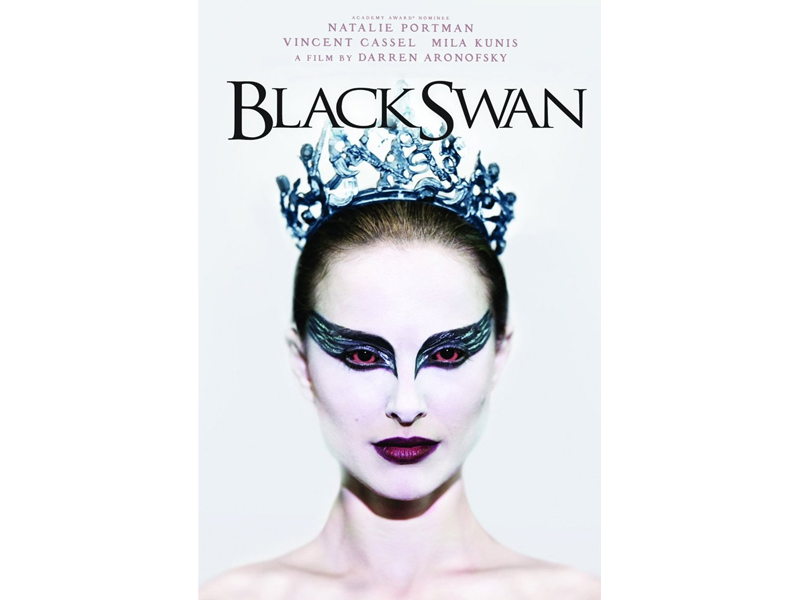

The restraint of the 1990s and early 2000s necessitated commissioned jewelry that was central to the storyline. Schpak made tiaras worn by Julie Andrews and Anne Hathaway in The Princess Diaries and one for Natalie Portman in Black Swan. She made a pocket watch for Tom Hanks’s character in Castaway. More recently, the surge in high-production television has benefited Schpak, and she has made historically appropriate pieces for the Showtime series The Tudors and the Cinemax series The Knick. The design and fabrication of metal police badges seen on countless television and film productions has provided Schpak with the steady income needed to keep a small business like hers afloat. She calls the custom police badges the “bread and butter” of her business as they allow her the financial freedom to accept more creative and challenging work.

Schpak has never advertised, nor does she have a website, but word of mouth has provided her with unexpected clients. Schpak works with the California-based fashion label Rodarte, creating belts, earrings, necklaces, and hair ornaments that are essential to the runway looks. The designers and creators of the label, sisters Kate and Laura Mulleavy, are known for creating dreamy, romantic, and unconventional clothing that has garnered the attention of the fashion and art world.

In addition to their fashion line, the Mulleavy’s have created costumes for the stage and screen and designed clothing explicitly for museum installation. In 2012, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s Costume and Textiles department acquired and displayed a group of gowns designed by the sisters, entitled Rodarte: Fra Angelico Collection. Intended as art objects rather than functional clothing, the garments were displayed on custom invisible mounts suspended from the ceiling within a gallery of Italian Renaissance art. Schpak’s commissioned pieces for this collection have considerable visual impact, providing the garments with dimensionality and texture and strengthening the connection between the gilt in the Renaissance paintings with the Rodarte garments. The jewelry and accessories Schpak made for the Fra Angelico collection served as her introduction to the curatorial team in the Costume and Textile department at LACMA.

In the very early stages of planning Reigning Men, curators Sharon Takeda, Kaye Spilker, and Clarissa Esguerra decided that each mannequin would show a fully accessorized example of menswear and that this look would include jewelry when applicable. For many of the looks, prop jewelry was found and purchased, but for the earlier pieces a custom reproduction from Schpak was needed. According to curator Esguerra, one of the first looks developed for the exhibition was the “macaroni male,” an extravagantly clad British youth of the 1760s and 70s. After taking the “grand tour” throughout Europe, these young men of means returned to England donned in the latest fashions, with a taste for the then-exotic Italian pasta, macaroni. The macaroni man was a popular target for satire, and the team at LACMA used original caricature illustrations to cull together a fully dressed representation. The equipages hung from either side of his waist, which Schpak fabricated for this exhibit, were meant to aide the wearer in gracefully extracting his pocket watch out of narrow pockets. Esguerra explains that wearing two equipages, instead of one, represents the “gratuitous display of jewelry for a man who was considered the ultimate example of conspicuous dressing.”[1] The macaroni’s unusually colored, Italian-cut suit would have been enough to set him apart from his peers, while the inclusion of a high wig, corsage, and double equipages on the mannequin signal the extremity of his style to both contemporaries and the modern museum visitor.

Schpak also created jewelry for the representative of the Beau Brummel-esque dandy of the 1820s. Unlike the macaroni, restraint and detail were paramount to the dandy’s identity, and his fashionable appearance was well documented in fashion plates and discussed in written source material. The fob on display has only a seal and a watch key and is secured with a simple white ribbon for a subtle, utilitarian effect. To create the jewelry, Schpak raided her vast supply of metal findings, customizing each one by cutting and soldering different pieces together. She used brass hexagonal tubing to create delicate watch keys, which were hung from ribbons or chains. Guiding her process was the research provided by the curatorial team; together, their objective was to create historically accurate pieces that contributed to the overall look without distracting from the garments on view.

As proprietor of the Studio Art Metal Shop, Schpak is dependent not just on making a beautiful object or an interestingly designed object; her success is reliant on her ability to further ideas and themes through jewelry and metal objects. When asked if she sees herself as an artist, a designer, or a craftsperson, Schpak responded, “I think some jobs I’m an artist. I figured it out. I know what it looks like. They didn’t have any idea—I did and everybody’s crazy for it.”[2] With other jobs, like the jewelry pieces in Reigning Men, the finished product is the result of a collaborative relationship, one where she lends her expertise and the client reaps the benefits. Schpak’s work is rarely credited, yet it continues to give dimension to characters, whether on screen or on a museum platform, lending a stylistic authenticity that audiences unknowingly appreciate.