Jewelry has long been a language, a carrier of hidden meaning, full of symbols. It can be a tool of self-expression, a link to home and culture even from far away, a personal talisman, and a form of resistance.

The 20th century, shaped by change and innovation, made space for bold and new ideas—witness the use of unusual materials and techniques, which bring new forms and meanings. In Poland, this happened in the shadow of war and Communism, deeply shaping how artists worked.

But First, Art Deco Meets Folkloric Charm

In 1923, the first Workshop of Metal Techniques opened at the Warsaw School of Fine Arts, from which a key character originated—Henryk Grunwald. He created designs brought to life by Stefan Chmielecki and Wojciech Jurkowski. Their style, combining folk motifs with the Art Deco aesthetic internationally popular at the time, stayed popular even after World War II.

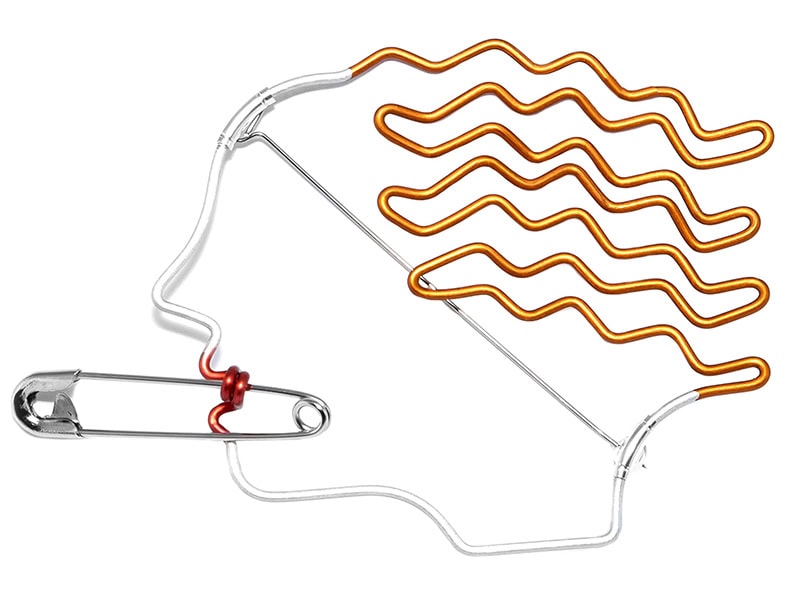

Józef Fajngold also used Art Deco ideas in his jewelry. He was both a goldsmith and sculptor. His graceful and decorative Female Head brooches and sculptures clearly drew on interwar modernism.

Folk Motifs and Socialist Realism

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, artists in countries influenced by the Soviet Union had little freedom under the doctrine of socialist realism. Art must be “socialist in content and national in form.” Even applied arts like jewelry had to follow this rule. The political condemnation of the avant-garde and of abstraction resulted in an emphasis on the figurative nature of representations in art.

The popularity of folk motifs in Polish goldsmithing and metalwork therefore continued. Among them, we frequently see characters from legends: the Warsaw Mermaid, the wizard Mr. Twardowski, and the Dancing Robber. Artists used folk floral patterns, traditional filigree techniques, and local stones such as agate, nephrite, and Baltic amber.

Anything Valuable? Not Available

After World War II, Poland’s economy was in crisis. The state plan to rebuild the country meant many materials were in short supply. Gold was banned, silver was limited. There were no tools or machines for workshops. Jewelers had to adapt and get creative. It thus became popular to use cheaper, readily available metals, such as copper and brass.

Craftsmanship for the People

In the centrally planned economy of postwar Poland, handicrafts cooperatives were created. On the one hand, they allowed the state to monitor jewelry production. On the other, they drew on the ideas of the English Arts & Crafts Movement of the 19th century. They aimed to revive traditional skills and build partnerships between designers and skilled metalworkers.

These cooperatives operated from the late 1940s and 1950s until the political transition of the 1990s, focusing on creating handmade, affordable jewelry for everyday people. Each cooperative had its own style, but overall their jewelry was decorative and full of ornament. Common features included filigree and milgrain techniques (especially in pieces made by the Imago Artis workshop); large rings with cabochon stones such as agate, quartz, amber, coral, or nephrite; and textured metal surfaces, which became a trademark of the ORNO cooperative.

Interestingly, today, after years of oblivion, jewelry from this period has again come into fashion, in tandem with the rising popularity of vintage items. Jewelry from cooperatives such as Rytosztuka, ORNO, Imago Artis, and Metaloplastyka is becoming more and more desirable and expensive.

A New Era of Artistic Expression

In 1959, Lena Kowalewicz-Wegner started a jewelry studio at the State Academy of Fine Arts in Łódź. This was an important step in recognizing goldsmithing as an artistic discipline. The establishment of the jewelry studio at the academy marked a move away from purely craft-based practice toward an artistic and design-oriented approach. Influenced by avant-garde ideas, Lena Kowalewicz-Wegner introduced abstract thinking, material awareness, and experimentation into the field—treating jewelry not only as decoration but as a form deeply connected to the shape and movement of the body, to clothing, and to artistic expression. Today, the Institute of Jewellery in Łódź is the oldest and most active program of its kind in Poland.

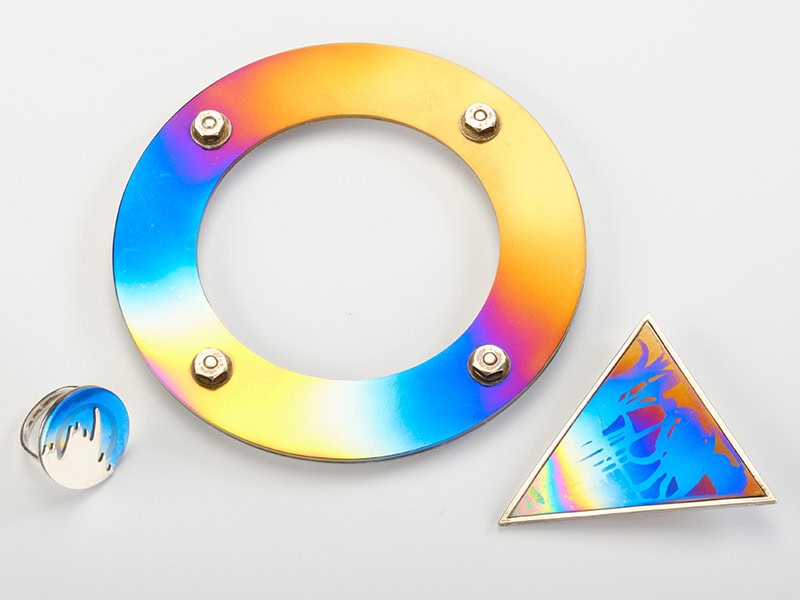

In the 1970s the decorative style of earlier decades gave way to simplicity and abstraction. Artists began to focus on form and explore new ideas and materials like paper, aluminum, Plexiglas, textiles, and plastic—drawing inspiration from trends that were then emerging in Western Europe. Jadwiga and Jerzy Zaremski and the UFO Group—Jacek Byczewski, Jacek Rochacki, Joachim Sokólski, and Marcin Zaremski—were the pioneers of this new wave of Polish goldsmithing. Their work had clean lines and geometric shapes and was made with great care and skill. They influenced the next generation of designers, including Andrzej Bandkowski, Jarosław Westermark, Jerzy Szymula, and Tomasz Mayzel.

A key date for the development of jewelry in Poland was 1974. At that time, the Zaremskis won a gold medal at the Internationale Schmuckschau at the Handwerkmesse Fair in Munich. Their necklace, made from one polished metal sheet, was the first Polish jewelry to win such a prize. It was a major moment not only for the authors but also for the whole goldsmithing community in Poland, as it recognized their innovative and experimental style within the Western European contemporary jewelry scene.

Amber: The Gold of the North

To understand Polish jewelry, one must understand amber. This “gold of the North,” found along the Baltic Sea, has long been part of the region’s culture. In the second half of the 20th century, amber jewelry underwent major changes.

Early postwar amber pieces often had melted, shapeless forms and floral decorations. Artists set large amber cabochons in big rings, bracelets, brooches, and pendants. Over time, a new group of designers, including Jacek Baron, Marcin Zaremski, and Prof. Andrzej Szadkowski, broke away from these traditions. They created modern designs that gave amber a new identity, one which is still being developed today by successive generations of jewelry artists.

A great example of how nowadays Baltic amber can be used in contemporary jewelry in a fresh, innovative way—without any trace of kitsch or vintage clichés—can be found in the work coming out of the Experimental Design Studio at the Academy of Fine Arts in Gdańsk, led by Professor Sławomir Fijałkowski, a jewelry designer, curator, and expert in the field of contemporary art jewelry. The studio’s projects combine amber’s traditional legacy with cutting-edge technologies such as CAD/CAM, VR/AR, and 3D printing.

Jewelry as a Symbol of Resistance

Jewelry is worn close to the body, which gives it the intimate power of using it as a language. It can express things that cannot be said out loud.

One of the most powerful examples of jewelry used as a protest in the Communist period was the resistor brooch. A resistor is a small, widely available component used in electronics. In a play on words, people often wore them as pins to signal quiet defiance. That symbol of resistance against oppressive authority became so popular in the 80s that wearing it was not without risk of harassment, despite the fact that there was never an official ban on wearing them.

A goldsmith, Mariusz Pajączkowski, made several dozen resistor pins framed in silver in the 1980s. The first one he ever made was returned to him 23 years later by the person who wore it. It’s a small object—but full of meaning and memory. Today it is in the jewelry collection of the largest Polish collector of contemporary Polish goldsmithing art—Maria Magdalena Kwiatkiewicz.

In other works, Pajączkowski also used symbols of national resistance to express opposition to Communist rule. He created versions of the Fighting Poland anchor—a symbol used by the Polish underground—made from silver spoons, and he used Polish coins with the national eagle emblem.

In 1980, a year before the imposition of martial law in Poland, silver and copper rings by the goldsmithing couple Lucyna and Marek Nieniewscy received awards at the 2nd National Review of Goldsmith Forms “SILVER.” The rings looked like wall sockets, which was a subtle reference to the former electrician Lech Wałęsa, the leader of Poland’s democratic opposition at the time.

The Enduring Spirit of Polish Jewelry

The fall of the Iron Curtain, in 1989, changed everything. The political shifts of the 1990s in Eastern and Central Europe brought a wave of globalization and rapid technological growth. As the world has become more connected, Polish artists actively seek opportunities to present their work beyond the country’s borders.

Today in Poland there is no shortage of talented and creative jewelry artists. Some of them continue to explore political and social themes in their work. They address issues such as environmental pollution, consumerism, or the women’s protests against the tightening of abortion laws in Poland (2020–2021). Others use jewelry to reflect on personal stories, memory, or cultural identity—confirming its lasting role as a medium for meaning, emotion, and a way of responding to the world around us.

While some artists, like Marcin Bogusław, continue to use traditional techniques and materials such as silver—but in contemporary ways—others take a more experimental approach, often working beyond goldsmithing. Jolanta Gazda uses crochet techniques with silver and copper wire. Michalina Owczarek‑Siwak practices upcycling, incorporating materials like old flyers into her pieces. Sława Tchórzewska merges jewelry with painting. And Małgorzata Kalińska experiments with freely shaped epoxy resin to create sculptural forms.

Many artists explore a wide range of subjects through narrative jewelry, using it to express views on both personal and societal issues. The themes mentioned here—ecology, protest, identity, memory—represent only a small part of the broader landscape. These examples offer a glimpse into the diversity of voices and perspectives found in contemporary Polish jewelry. Arek Wolski, for instance, reflects on ecological concerns and overconsumption. Zofia and Witold Kozubscy created a series of aluminum brooches during the women’s protests in Poland. Sergiusz Kuchczyński, concerned about the rising hostility toward immigrants, designed a series of brooches inspired by the tradition of leaving an empty plate at the Christmas table for a stranger in need.

This kind of conceptual and narrative approach—treating jewelry not just as adornment, but as a form of communication—is supported by key institutions in Poland. The Institute of Jewellery at the Academy of Fine Arts in Łódź is one of the country’s leading centers for jewelry education. Several museums and galleries are also dedicated to supporting and exhibiting contemporary jewelry, including the Gallery of Art in Legnica, the organizer of the Legnica Jewellery Festival SILVER; the Goldsmithing Museum (department of the Vistula Museum in Kazimierz Dolny); and YES Gallery, in Poznań, founded by collector Maria Magdalena Kwiatkiewicz.

Still, jewelry as an art form remains relatively underrepresented in major Polish art institutions. With limited visibility in contemporary art museums and galleries, the field remains overlooked in the broader art discourse. Supporting the international presence of Polish artists and encouraging their involvement in global initiatives is key to building greater awareness—and ensuring that these powerful, wearable stories are seen and heard both in Poland and beyond its borders.

The opinions stated here do not necessarily express those of AJF.

We welcome your comments on our publishing, and we will publish letters that engage with our articles in a thoughtful and polite manner. Please submit letters to the editor electronically; do so here. The page on which we publish Letters to the Editor is here.

© 2025 Art Jewelry Forum. All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. For reprint permission, contact info (at) artjewelryforum (dot) org