Francesco Pavan passed away peacefully in his sleep in Padua, Italy, on July 17, 2025, at the age of 87. Born in Padua on October 13, 1937, he was one of the masters and pioneers of the Padua School, whose identity and recognition he helped forge by elevating jewelry into a conceptual art form, redefining the technical possibilities of gold, and spreading its poetic language across the world.

A celebrated artist, honored by institutions and collectors alike, his works are housed in prestigious collections such as the Kunstgewerbemuseum (in Berlin); the Musée des Arts Décoratifs (Paris); the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; the Schmuckmuseum (Pforzheim); and in the private collections of patrons such as Marzee and Helen Drutt. Pavan was the recipient of numerous awards: the Goldmedaille, at the Internationale Goldschmiedeausstellung, in Munich, in 1968; the Herbert Hofmann Prize, in 1973, 1985, and 1989; and the International Jewellery Art Prize, in Tokyo, in 1986. Yet, above all, he was a generous teacher whose gravitational center was the Pietro Selvatico Institute of Padua—first as a student, graduating in 1955 with a diploma in metal and repoussé arts, and then, from 1961 to 1999, as a beloved instructor in the newly founded goldsmithing department.

Pavan devoted his life to teaching—not just as the transmission of techniques and knowledge but as a profoundly human exchange. His love and passion for the craft, his willingness to share, touched generations of students who remember not only his goldsmithing mastery but his kindness, patience, and gracious spirit. One of his most brilliant pupils, Stefano Marchetti, commemorates him in these words:

“I was fortunate to meet Francesco Pavan as soon as I arrived at the Selvatico. He was my teacher of techniques, and our meeting proved decisive—for my artistic formation, and as a human anchor. Great artists are often protective of their connections, but Francesco was incredibly generous. He introduced me to his collectors and galleries, gave me wise advice, and was always by my side.”

Pavan’s journey in goldsmithing began under the mentorship of Mario Pinton, first at the Selvatico Institute and then in Pinton’s atelier. Pinton’s participation in the 1951 IX Milan Triennale—where he presented a repoussé gold bracelet and a cast vegetal composition—launched the Padua School with a radical reimagining of jewelry, no longer as mere technical or decorative craft but as an integrated art form, echoing contemporary expressions. From Pinton to his gifted pupils, Pavan and Giampaolo Babetto, and through the generations of goldsmiths nurtured at the Selvatico, the Padua School became an international movement—Italy’s most significant contribution to postwar research art jewelry.

This artistic vision, founded on geometric clarity and compositional rigor, forsook ornamental flourish to celebrate the intrinsic power of gold: molded, mastered, made meaningful. Pinton also built bridges between the Milanese artistical milieu and Padua’s goldsmiths, bringing Pavan into contact with artists including Lucio Fontana and the Gruppo N, which led him to many collective exhibitions—including the 1964 and 1966 Venice Biennales (32nd and 33rd editions), where he was featured in the Decorative Arts section.

From this vibrant Italian artistic ferment of 1960s, Pavan distilled into his jewelry a language of formal abstraction, conceptual rigor, and sculptural purity. Ornamentation gave way to essence. This purity was accompanied by a relentless technical exploration—one of his most fruitful obsessions. “My research, my project, lies in building the jewel until it becomes form,” he said recently. In this evolution of forms, his artistic language reveals itself through three principal directions: the module, the weave, and the enamel.

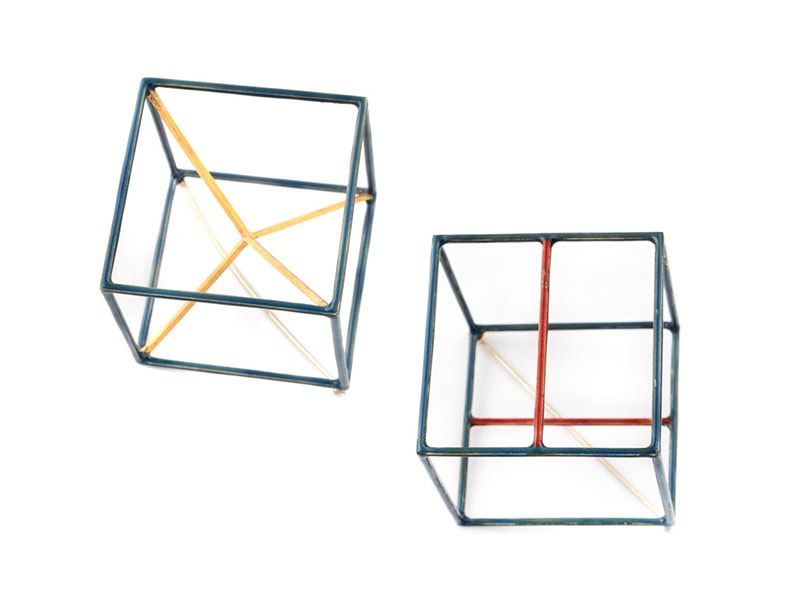

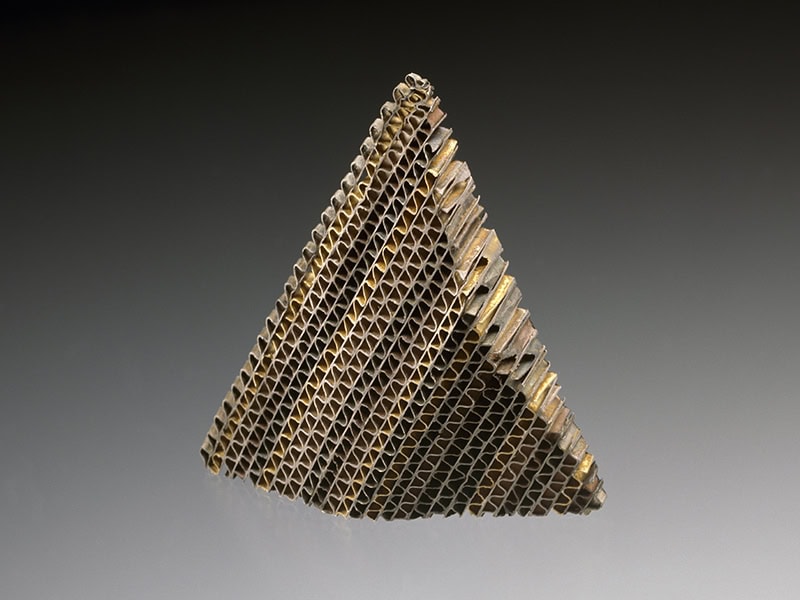

His early works introduced the geometric purity and Cartesian clarity—squares and structures in opposition to the organicism of traditional jewelry—that became a sign of the Padua School, which he interpreted with elegance and restraint. But it was through weaving metals that Pavan achieved full artistic maturity and a distinct visual grammar. These woven works—crafted from gold, silver, copper, and nickel silver, hammered and threaded—radiate luminous chromatic intensity and a kinetic depth. Deeply connected to the women of his life—his wife, Lella, and daughter, Chiara—Pavan began weaving metals in the 1980s, while his daughter was studying textile arts at Selvatico. It was a fusion of affection and creativity, intersecting tools, mediums, and disciplines in a way that only true artists can achieve.

The third and final phase of his oeuvre saw him turn to enamels. At the threshold of the new millennium—his artistic legacy just very well affirmed—he boldly reinvented himself, exploring enamel not as a surface but as a volumetric element. Using enamel as a luminous border, he brought out its transparent hues with rare poetic insight. This fearless experimentation—across technique, material, and form—defined Pavan’s spirit: curious, humble, determined, tireless.

I have always deeply admired both the artistic and human qualities of Francesco Pavan—a reserved and discreet man, yet immensely generous and gifted. A gentle soul, with smiling eyes and elegant manners, a man of few words but of immense heart. When I was curating the Art Room at the Vicenza Museum of Jewellery, it was deeply important to include one of his works—both to honor the Museum’s connection to its region and to pay tribute to the Padua School’s masters. He had no works available at the time, but he yielded to my insistence by finding a magnificent necklace in gold and niello that perfectly embodied his powerful artistic language—a dance of light and shadow, transforming jewelry into fluid and elegant sculptures for the body. His vision was one of threads and textures, of voids and volumes—a conceptual pursuit defined by force and purity.

Thank you, Francesco, for your art and for your gentle heart. You will be dearly missed.

We welcome your comments on our publishing, and we will publish letters that engage with our articles in a thoughtful and polite manner. Please submit letters to the editor electronically; do so here. The page on which we publish Letters to the Editor is here.

© 2025 Art Jewelry Forum. All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. For reprint permission, contact info (at) artjewelryforum (dot) org