Leslie William LePere was a rare golden soul. He was 24 karat. He was grade “A.” He had a solid #2 lead spirit, woven with originality, wit, and pure magic.

One of the great creative forces of his time, Les left behind a legacy that runs deep in the soils of eastern Washington and spreads far beyond—through illustrations, enamel works, friendships, and the countless people he inspired. On August 1, 2024, Les passed away peacefully in his sleep after a series of health issues. He was 78.

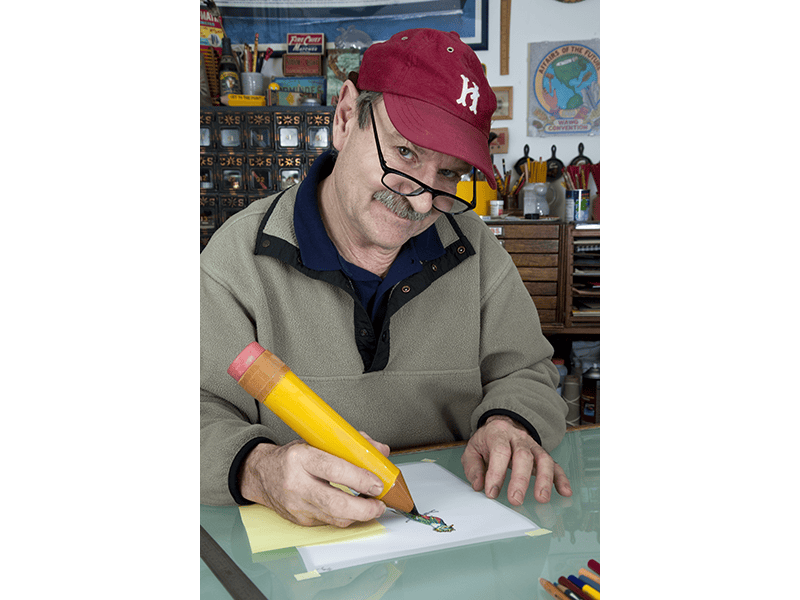

In his own words, Les “was a wheat farmer with an art habit” and a man who stored plenty of hats on his hat rack: wheat farmer, pencil wrangler, tractor mechanic, mustard connoisseur, Airedale lover, culinary wizard, observant European voyager, color swatch enthusiast, gearhead, and puzzle master, to name a few. Most importantly, he was a brother, uncle, teacher, artist, and trusted friend.

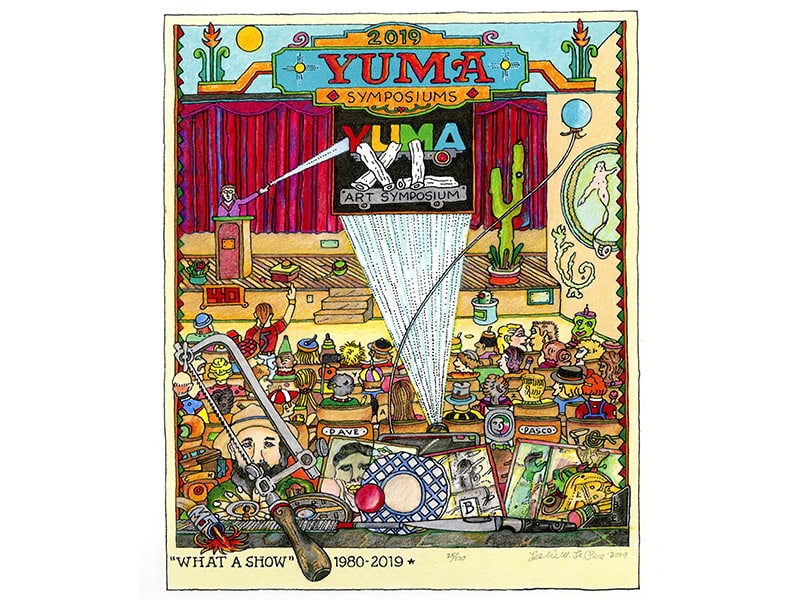

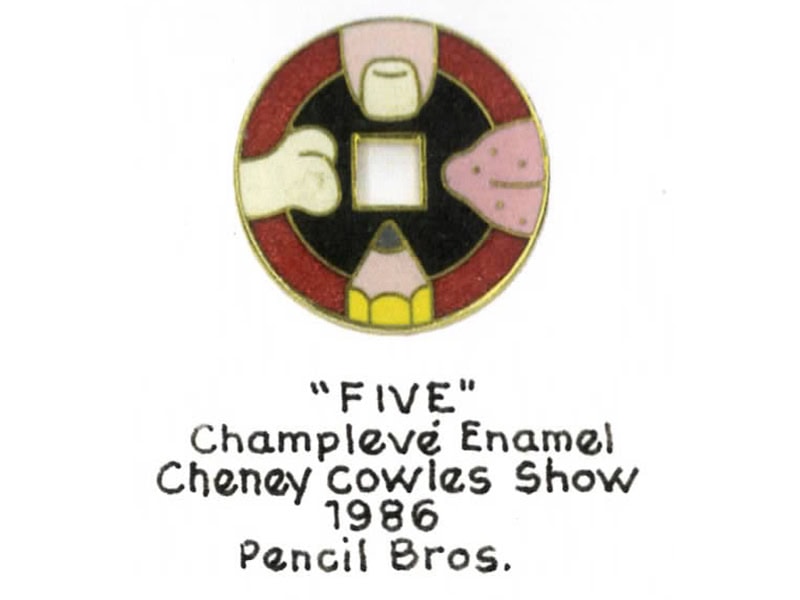

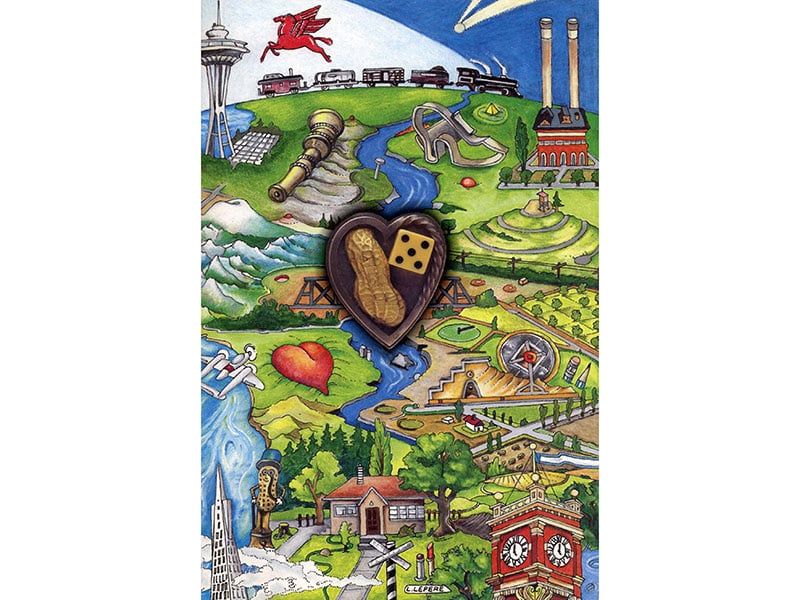

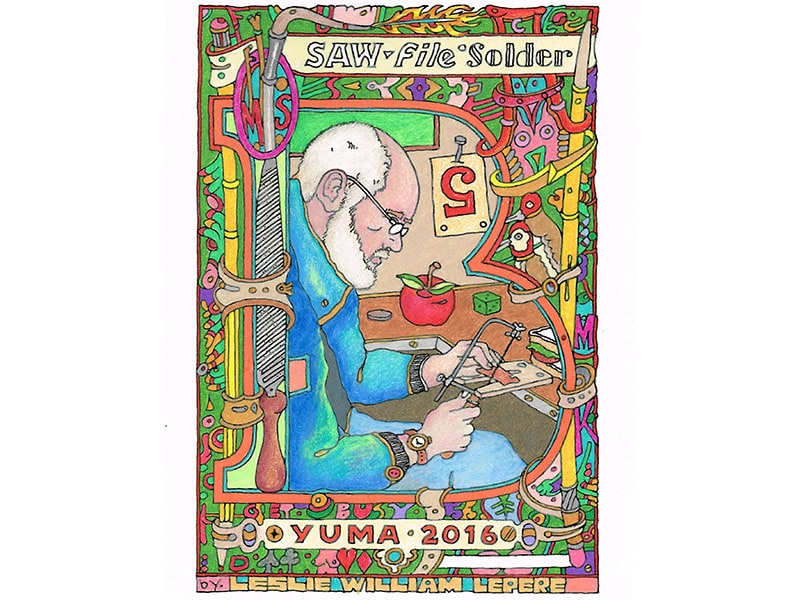

Les has left a lasting visual impact through the course of his rich and spirited career. Metalsmiths and lovers of contemporary enameling may recognize his illustrations from the poignant and symbolically rich work of the Pencil Brothers, a collaboration between Les and his creative soulmate, Ken Cory. Their champlevé enamels and illustrations have inspired many enamelists—Marissa Saneholtz, Zachery Lechtenberg, and Laura Fortune, to name just a few. And Les’s recent reconnection to the metalsmithing world inspired vibrant illustrated announcements for events like Smitten Forum, Yuma Art Symposium, ECU Material Topics Symposium, and The Bench Symposium, in Santa Fe.

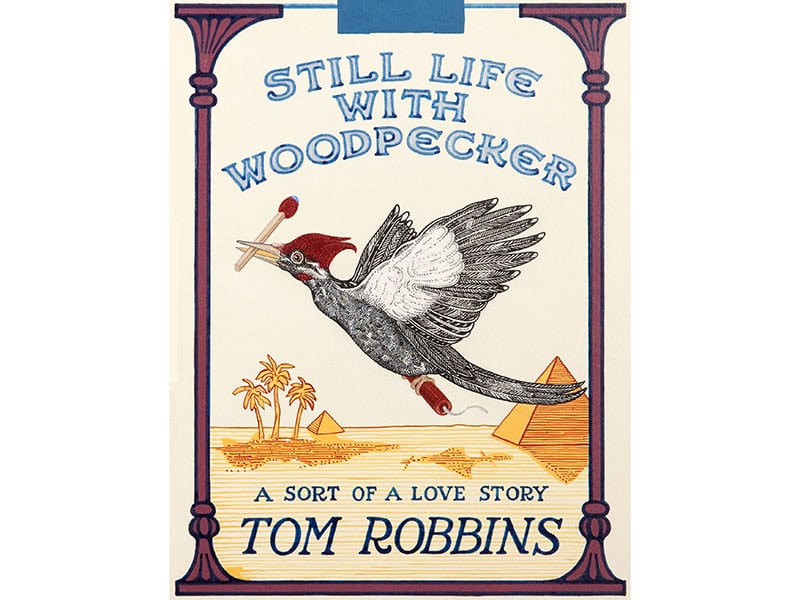

If you’re a bookworm, Les’s illustrations may have danced in your head. Most notably, the legendary Still Life With Woodpecker book jacket is widely recognized and celebrated by Tom Robbins fans around the world.

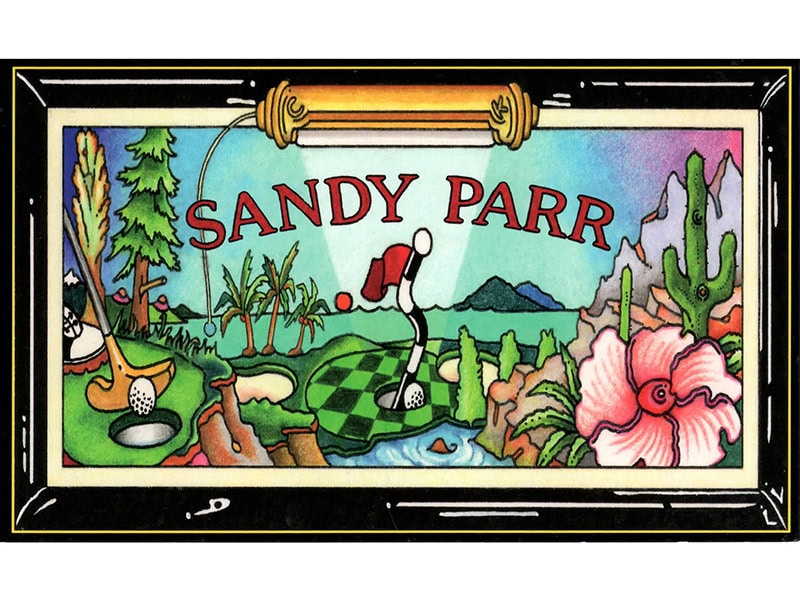

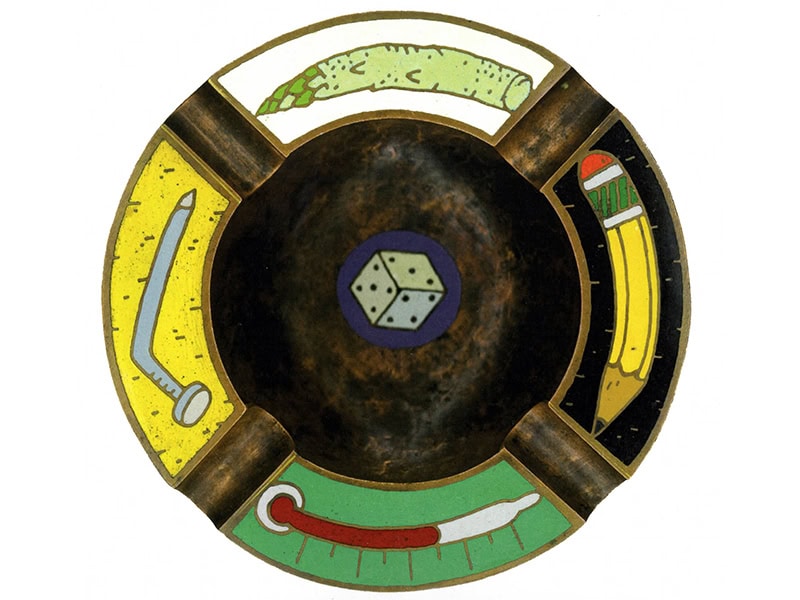

Or you may wear work from Sandy Parr, a collaboration between Les and his good friend and business partner, Charlie King. Their distinctly intricate hard-fired champlevé enamel lapel pins, golf-ball markers, and belt buckles (with backs just as interesting as the fronts!) highlight the representational narrative for many clients’ anniversaries, fundraisers, non-profit organizations, golf clubs, and ski resorts. They are highly revered by recipients around the country.

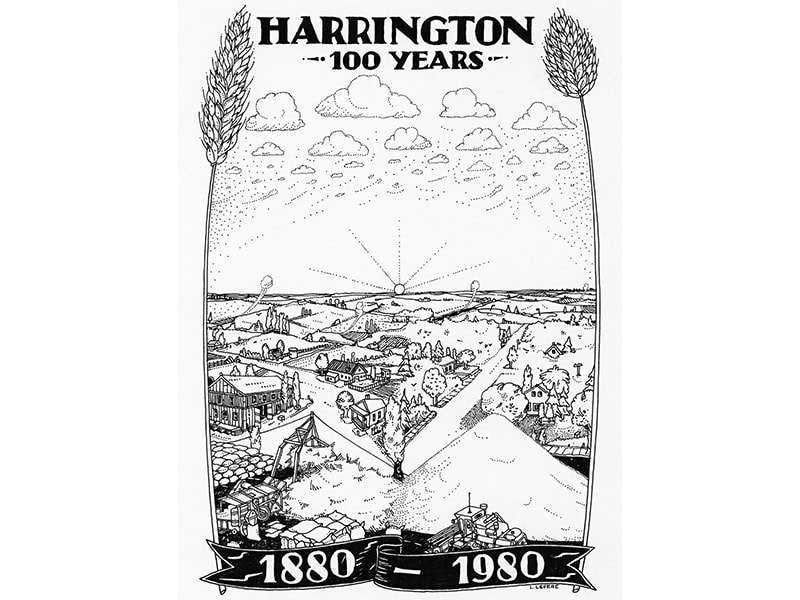

And if you grew up in the Northwestern United States, chances are you’ve seen regional advertisements brought to life by his electric illustration style. Les was the creative force behind many celebrated regional works including his iconic 1973 poster for the Bumbershoot Festival held in Seattle, or more recent logos for The Post & Office or Electric Hotel in Harrington, WA. But his graphic portfolio varies widely, with many logos, packaging designs, announcements, and posters leaving an impression on both individuals and businesses nationally.

I first met Les in the registration line at the 2015 Yuma Art Symposium, in Arizona. He was a tornado of energy and zest! Every conversation with him sparkled with wisdom and wit. I had admired his work for years. One of my metals mentors, the late Nancy Worden, had introduced me to the book Play Disguised: The Jewelry of Ken Cory, which Les and Worden created together to honor their mutual friend and creative collaborator. (If you haven’t seen this book, go find it! It does not disappoint.)

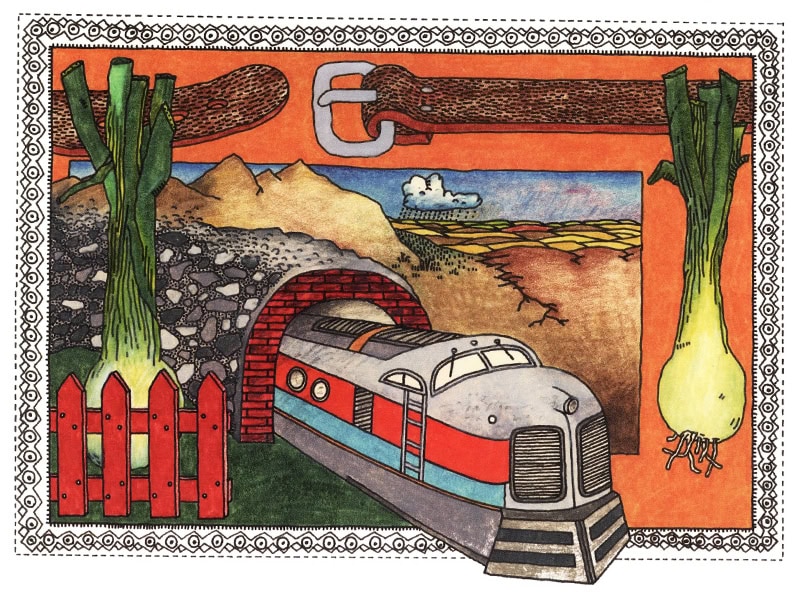

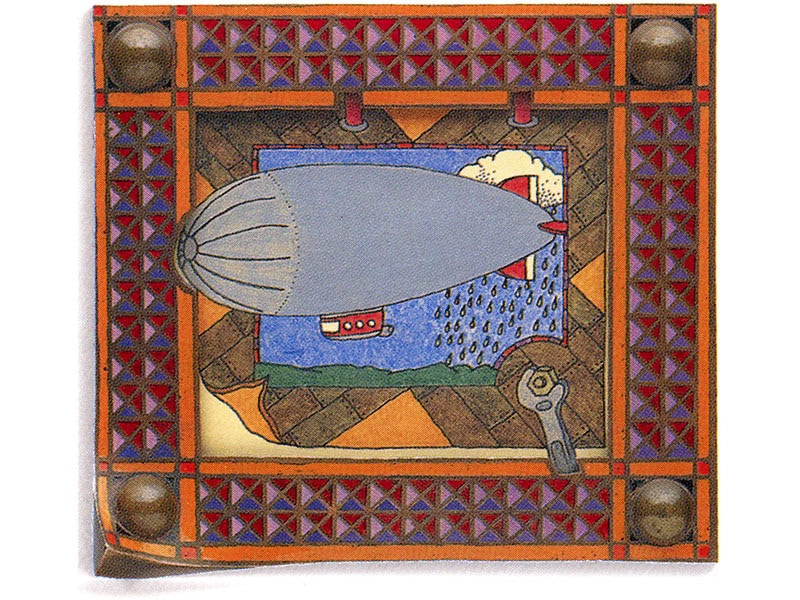

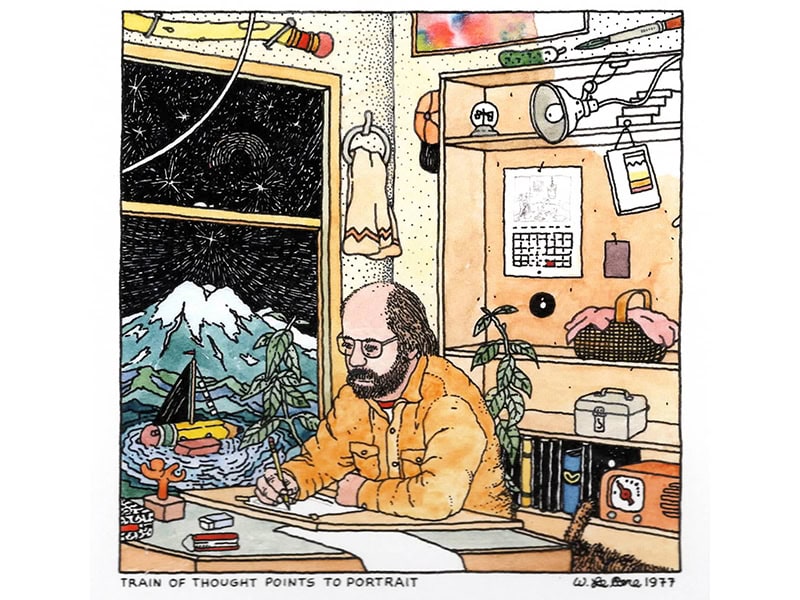

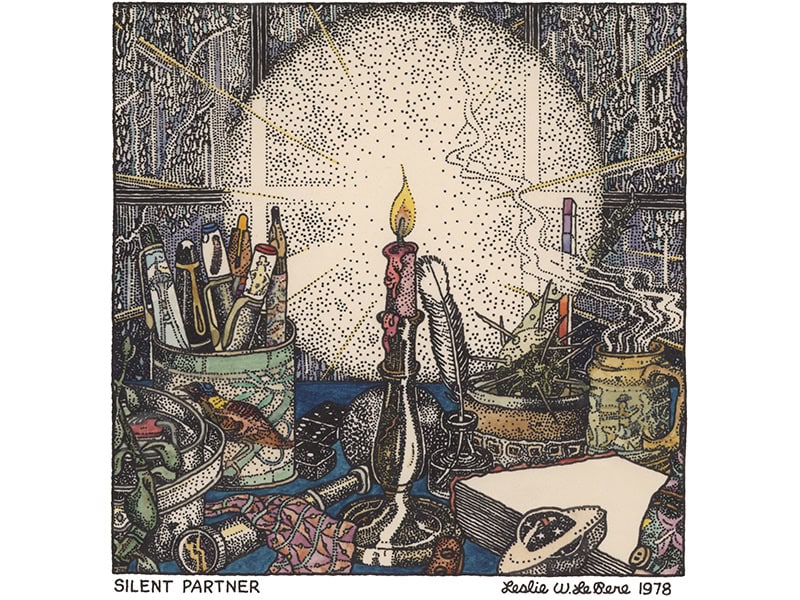

The Pencil Brothers section of the book captivated me. I would sit for hours poring over the illustrations, discovering all the small details, intelligent whimsy, and symbolism baked into every inch of Les’s drawings and the collaborative champlevé enameled frames.

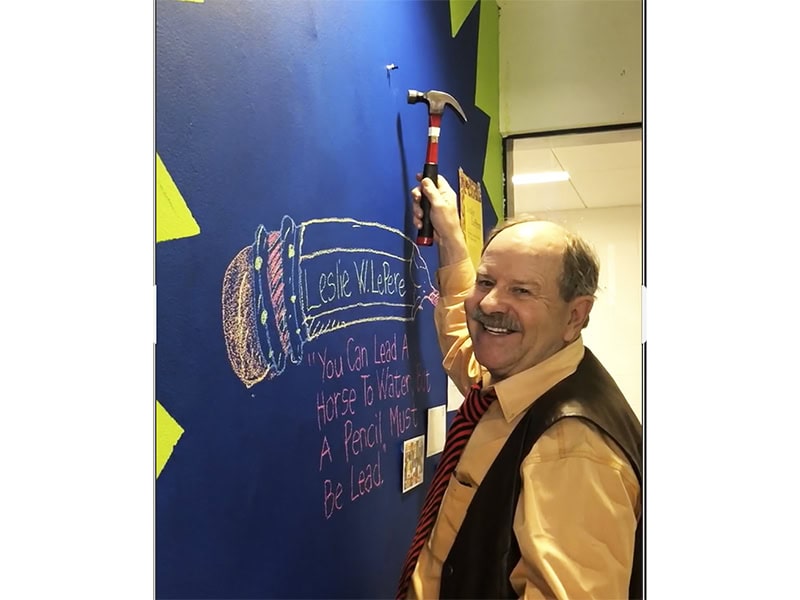

We got to be great friends over the next few years, talking every few days. I would often giggle with delight when I heard his voice on the phone. Les had a certain flair when speaking, drizzling in quirky conversational additions, like the “evers”: everwho, everwhat, everwhen, everhow. He called the computer the “confuser,” as it often left one in a state of confusion. “It surely would, Shirley!” And in a “moment of seriousity” it was a “lead-pipe cinch” to call Les a friend.

Other quips regularly heard from him: “You can lead a horse to water, but a pencil must be lead,” “It’s about as interesting as a spud sandwich,” and “Don’t forget, there is ‘art’ in the middle of ‘earth.’” He would often end his letters with the closing “Pencillistically.”

I loved to hear his recollection of dashing through the rain at Puget Sound to deliver the original acrylic painting for Still Life with Woodpecker. As he ran, a giant pileated woodpecker swooped down in front of him—the very bird featured in the painting under his arm! Les believed in signs like that and in the puzzles the universe laid out for us in life and in art. After he passed, I found a missing puzzle piece on my living room floor—one I thought he had stolen as a prank years ago! I couldn’t help but smile.

Les was born in Spokane, WA, US, and raised in a wheat-farming community in nearby Harrington. From a young age his mom encouraged him to be artistic, always supplying colored pencils and crayons for him and his sister, Louise. But he had only one art class before college, in which he made a pair of enameled cufflinks.

Les enrolled in architecture classes at Washington State University. Due to a bad ruler and a stiff environment, he struggled in his architectural drawing class and quickly became frustrated. The cookie cutter ideology and design methods were about as interesting as a spud sandwich to young Leslie.

Disappointed and confused, he looked to his sister for advice. Louise Kodis, now a well-known textiles artist living in Spokane, encouraged him to change course and take some art classes. So Les signed up, and the new direction provided him with the supportive environment he needed. His instructors praised his inexactitude. His individuality was nurtured and even encouraged.

After undergraduate, Leslie applied to, and was accepted by, University of Washington, Pratt, and WSU for graduate school. He chose to remain at WSU to take advantage of a teaching scholarship.

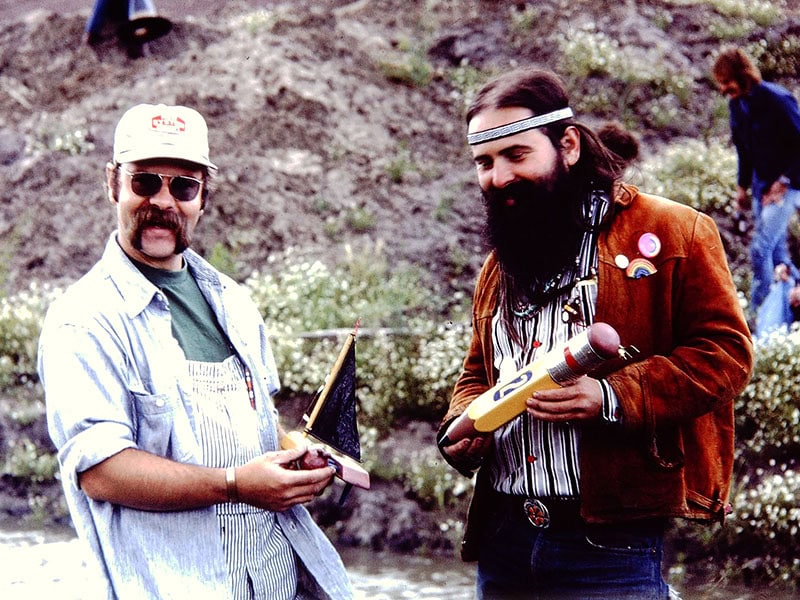

In 1966, during a summer ceramics class, Les found one of the greatest adventures in his life, his friendship with a long-haired metalsmith named Ken Cory. They bonded over the creation of a Jungian jug, car culture, and a fond distaste for the current art school flavor: abstract expressionism. Cory would be Les’s best friend and collaborator for many years, until his untimely death in 1994.

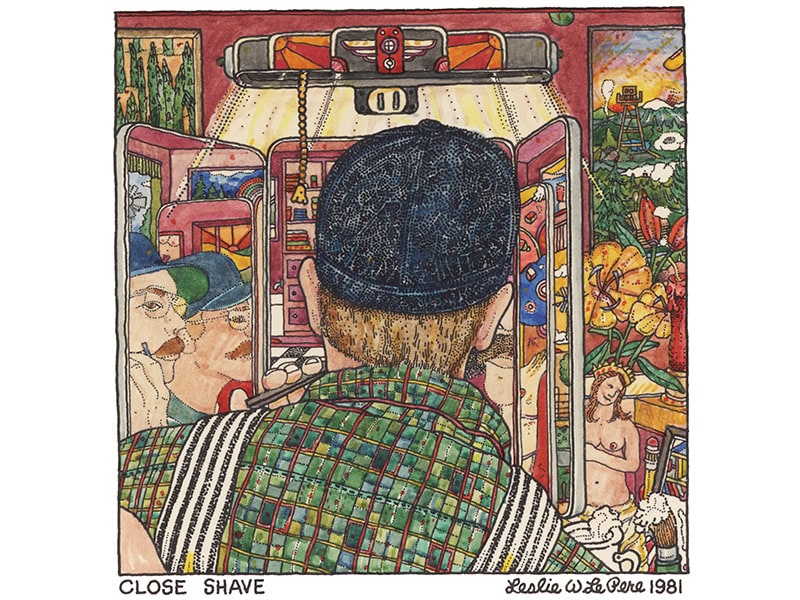

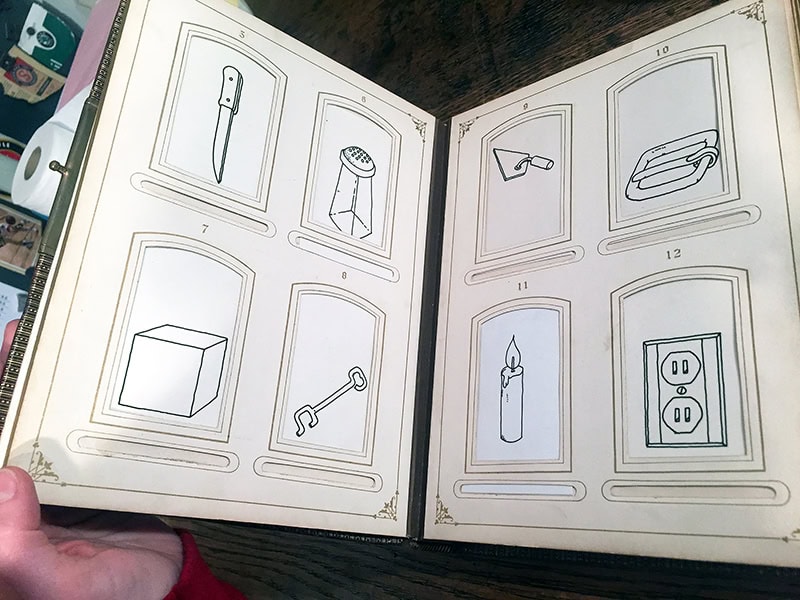

During their time at WSU they rebelled against abstract expressionism. In a lecture, Les later recalled, “We loved objects and things … so we reacted by being the opposite of large, colorful, and abstract. Our work was small, detailed, and representative.” All of which the establishment frowned on. To annoy their instructors even further, they produced their artwork as a collaboration.

They often picnicked in the woods with their cameras, sketchbooks, and jackknives to create sculptures out of sticks, assemble beach pebbles into portraits, decorate earth mounds with tiles. They even modeled each other’s likeness into sterling silver salt and pepper shakers. “Teachers at WSU were flabbergasted!” Les told me. “Musicians jammed together and so did we. We enjoyed our time together in creative exploration, not pandering to the museums and shows.”

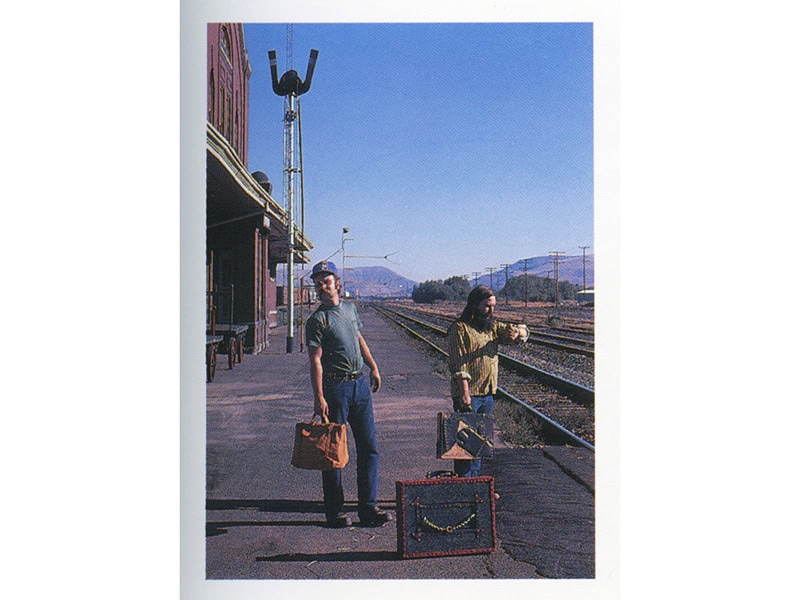

After graduation from WSU Les moved to Seattle to teach at a private school and began doing local graphics work, signing his name as “Pencil.” He and Cory continued their creative relationship on weekend visits.

Les would take the train to Ellensberg to see Cory and they jammed in the studio—illustrating on asphaltum with a manipulated ruling pen and etching down copper with ferric chloride “that would burn the hair off a hog at 50 feet!” He laughed when he told my students that, and then promptly reminded everyone to use a vent! He recounted traveling back to Seattle with no fingerprints because of the abrasive nature of the stoning process.

When they could not meet in person, they used USPS. Sometimes Cory mailed a metal frame to Les, who would then match it to an illustration, usually 4 x 4 inches (10.2 x 10.2 cm) in colored pencils and ink. Other times, Les mailed an illustration to Cory, who matched it with a frame. This occurred with the works Camel, Blimp, and Train.

They began signing their work as “Art Team” but found it “academic, dull, and dry!” Les often joyfully recalled the day he and Ken were reveling in the beauty and skill the car industry employed to create the hard-fired enamel Dodge Brothers radiator cap that Cory had found at a junk store.

Cory said, “Look at this emblem, LePere. Maybe we should be the Pencil Brothers. You can be Lead, I can be Red. Better Red than Lead!” Les spoke of his friend often, and with great reverence. Their collaborative works can be found in many museums around the country, including the Racine Art Museum, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Tacoma Art Museum, and Los Angeles County Museum of Art, among others. Their work has lit the creative torch for a whole generation of metalsmiths and enamelists.

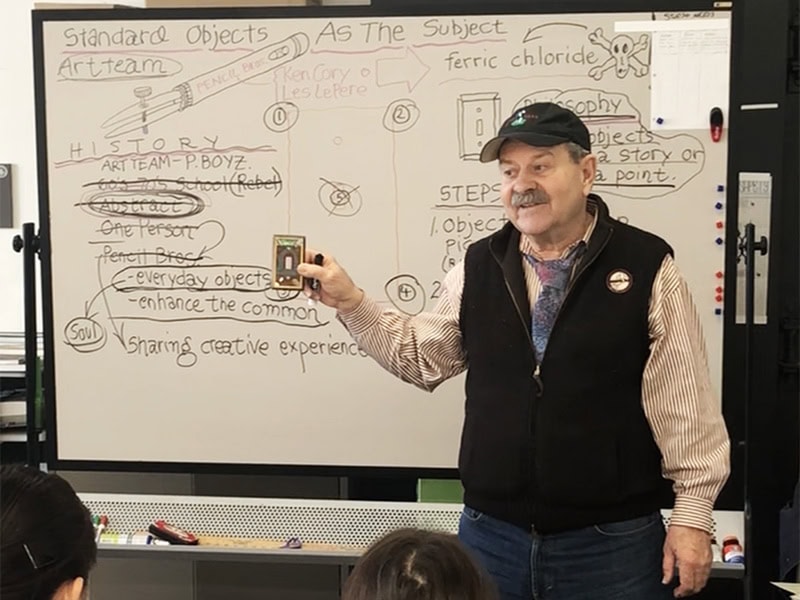

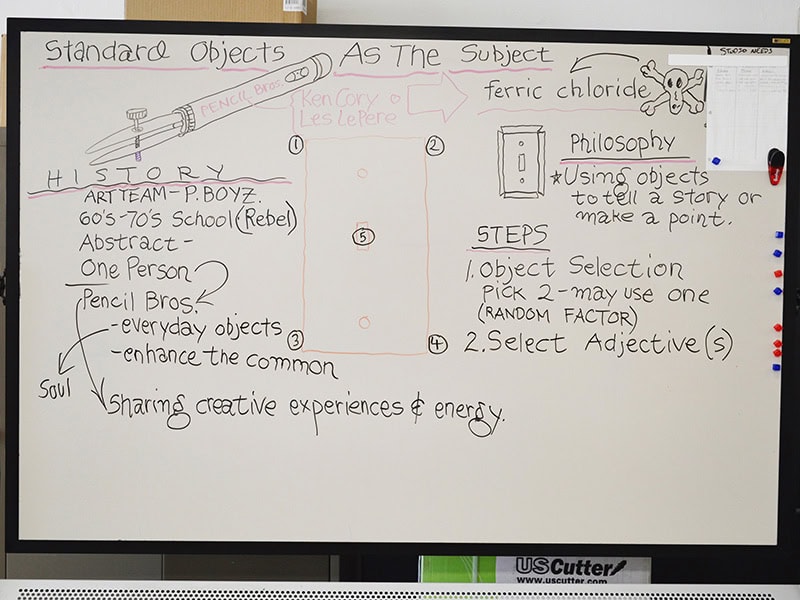

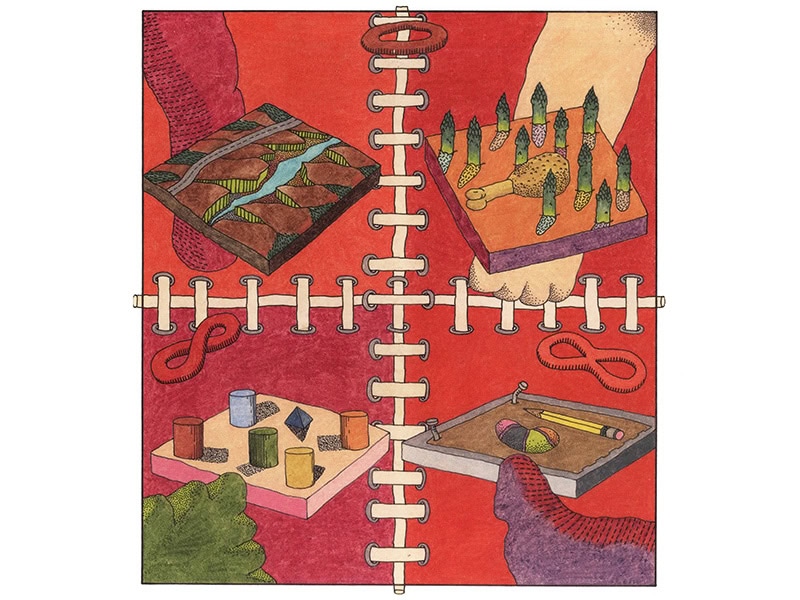

In 2018, Les visited my students at Western Michigan University. We spent months planning out his visit. The Pencil Brothers, representational imagery, and decorating functional objects to convey a narrative had ignited our fuse.

Les wanted to give them a framework, but leave them creative choice and a place to make their own path. Using his own graduate school object drawings as a base for exploration, students used decals with liquid enamel to adorn light switch plates for their homes. They were “shedding light” on the process of enameling, Les said. Beyond enamel, the 3-D design class used his drawings to inspire life-size sewn objects, and the advanced metals students created Pencil Brothers–inspired champlevé enamel frames depicting their personal narratives.

Les was an excellent instructor. He told my students how he once tried a new texture experiment with India ink and it went dreadfully wrong. He could have thrown his pencils across the room but instead designed his way out of it. “One thing we will always deal with in life is fixing something we break. You will need to course correct or adjust for your mistake. Always leave yourself an out! Be able to avoid and divert.”

He believed in the magic of collaboration, and how collective curiosity forged new paths and matured efforts in both projects and friendships. He believed in making time to study, researching your interests, and most of all, allowing yourself time to play. “Curiosity did not kill the cat! Cats love curiosity, it keeps them alive!” he said. “The sense of play is the backbone of serious work. The unknown and mysterious time with yourself coloring can open doors previously unknown to you. Allow yourself the time to look around and discover that you might just have what you need right in front of you. All is fair in love and art. Make it. Do it. Don’t stop.”

In 1980 Les returned to his family’s 3,000-acre wheat farm in Harrington to “play in the dirt,” as he called it. “I came back to Harrington because I knew I could use farming to support my art habit,” said LePere in a 2018 article for the Spokesman-Review.

Les led a full and creative life, devoted to the playful path, even when riding his combine through the rolling white wheat fields of eastern Washington. He described it as “driving to New York City and back every year at 4 mph!”

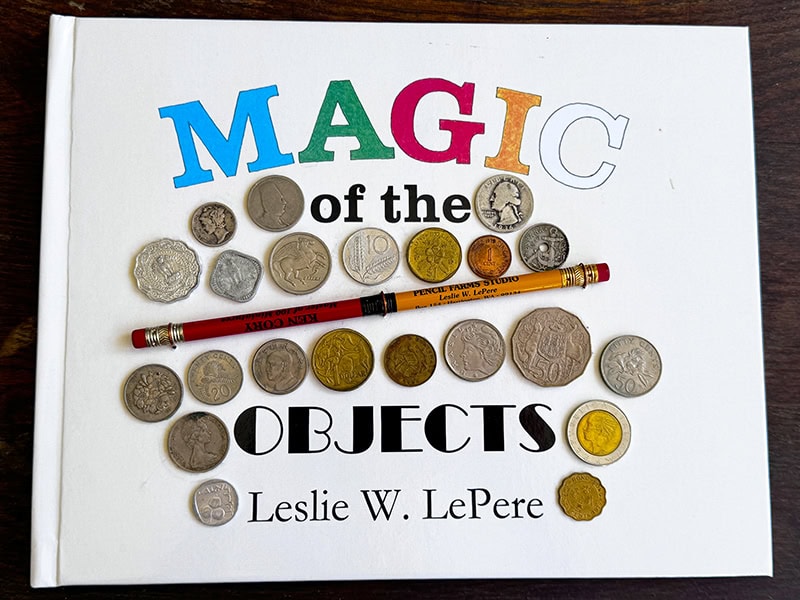

Les always kept pencils and paper in the combine cab, harvesting ideas along with the soft white wheat. When he got home at night, he would unpack those ideas and bring them to fruition in what used to be his mother’s dining room. He was a farmer by day and an artist by night. “It absolutely put a smile on my face and a song in my heart to know that I was able to combine both loves and passions,” Les told the Spokesman-Review in 2013, for an article coinciding with his retrospective Magic of the Objects, held at Jundt Art Museum, at Gonzaga University, in Spokane.

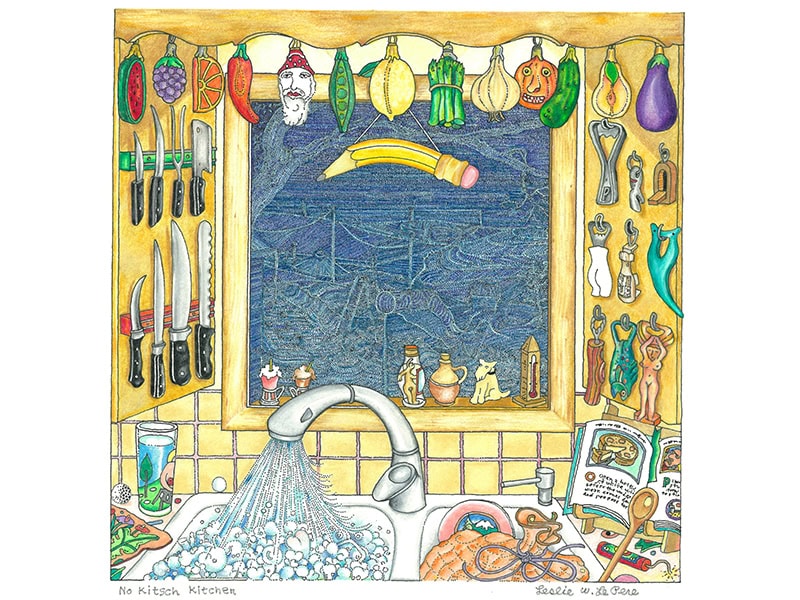

Les’s illustrations radiated an electrified reverence for his environment and the objects within it. His images—distillations of personal experience—were often laced with hidden meaning and set against vast landscapes, like wheat fields stretching to a broad horizon. He credits his life in Harrington with helping to mold his artistic vision. As he told the Spokesman-Review in 2013, “I think maybe growing up on the farm, where form follows function, had a great deal to do with it. I found myself falling in love with objects and shapes and recognizable things. To me, each of those recognizable things has a life, a karma, almost a philosophy of its own—thus magic.”

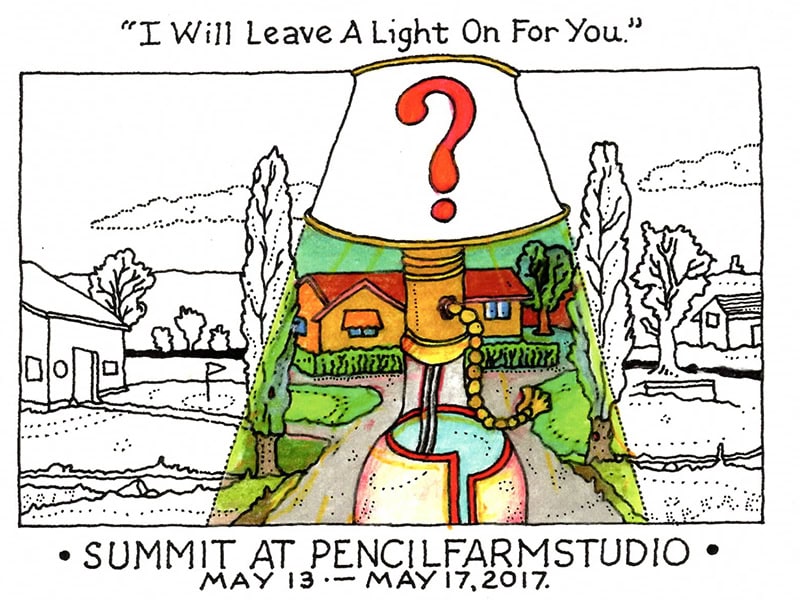

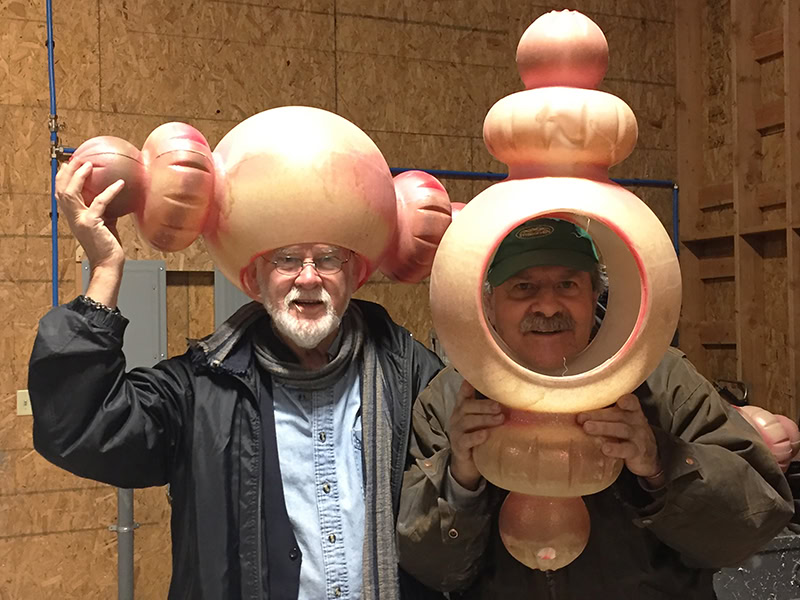

Les was generous with both his time and spirit. In 2017 he hosted a small creative residency at his “Pencil Farm” barn studio. We were all eager to step into his world, and had a blast in the studio doing it. Never one to take the obvious route, Les devised a group project: decorating lampshades. It wasn’t rooted in metalsmithing or illustration, which meant the creative playing field was wide open. We were free to explore, experiment, and simply enjoy making together. Les had spent weeks thoughtfully planning a fabulous lineup of local experiences to help us savor the spirit of Harrington. He was proud of his home, his community, and his roots. His hospitality went above and beyond anything we could have imagined. That was Les: ever inventive, ever inclusive.

Exploring the farm on that visit, I felt I was walking through one of his illustrations. The incredible collections of objects throughout his home adorned every surface like small altars igniting memories and connection to his past, silently conveying his stories around every corner of the room. The clouds in Eastern Washington really did look cartoonish—his pencils did not lie! And the random asparagus shoots poking up throughout the property made total sense now! I had always wondered about their presence in his illustrations. Gazing out over the expansive wheat fields, it was crystal clear where he drew inspiration.

Les LePere led a life full of grit, grace, humor, and wild creativity. He wasn’t afraid to challenge convention. He adored the handmade and the heartfelt. He was deeply rooted and wildly imaginative.

To know Les was to be inspired—and to laugh. And to miss him now is to carry forward the joy, curiosity, and artistry he brought to the world.

His legacy lives on in every person who picks up a pencil, pauses to appreciate a well-designed object, or believes that beauty belongs—even in a wheat field.

Additional information about Leslie and his artwork

LePere, Leslie W. Magic of the Objects: The Artwork of Leslie W. LePere. Jundt Art Museum, 2013

https://www.spokesman.com/stories/2013/oct/25/artist-captures-everyday-magic/

https://www.legacy.com/us/obituaries/spokesman/name/leslie-lepere-obituary?id=55876320

https://www.ruralrevival.co/stories/2019/8/27/there-is-art-in-the-middle-of-the-earth

https://hechoamano.org/post/13218-a-creative-excuse-31-leslie-lepere-re-release

https://www.spokesman.com/stories/2018/may/17/artist-leslie-lepere-continues-to-find-magic-in-th/

We welcome your comments on our publishing, and will publish letters that engage with our articles in a thoughtful and polite manner. Please submit letters to the editor electronically; do so here. The page on which we publish Letters to the Editor is here.

© 2025 Art Jewelry Forum. All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. For reprint permission, contact info (at) artjewelryforum (dot) org