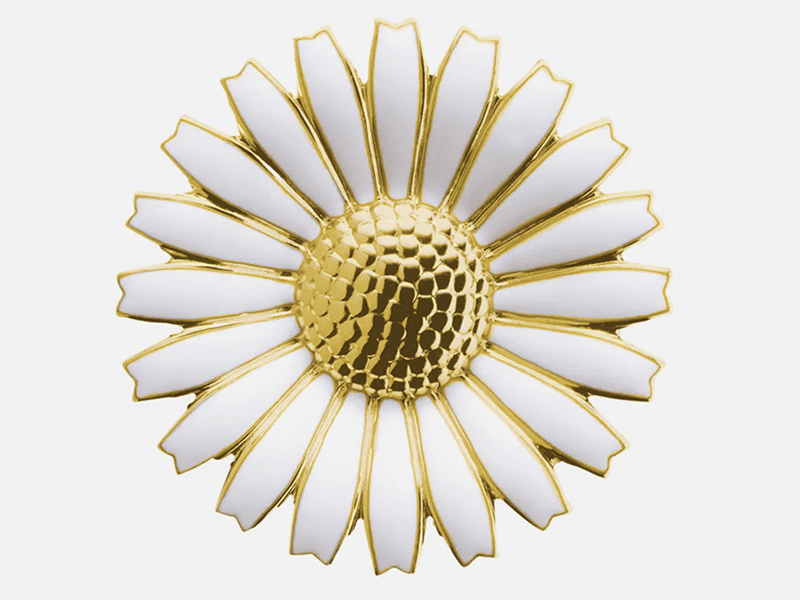

The Georg Jensen Daisy brooch is one of Denmark’s most recognizable pieces of jewelry. It was designed by Anton Michelsen in 1940 to commemorate the birth of Princess Margrethe, now Queen Margrethe II. It has since then become a symbol of Danish pride and unity. Far more than a decorative accessory, the brooch functions as a marker for tradition and collective identity in a country often cited as an example of societal progressiveness. Yet Denmark remains one of the most inaccessible countries for outsiders such as refugees and migrants. This striking contradiction reveals dissonance between the country’s progressive image and its exclusionary practices.

Art and politics often play hand in hand, and jewelry can act as a powerful vehicle for political commentary. Once worn, jewelry allows concepts to break outside the walls of the traditional white cube and enter public life. Danish jewelry artist Kim Buck creates politically engaged pieces by subverting iconic national symbols. Using objects such as the Daisy brooch, he critiques cultural uniformity and the selective memory that shape Danish identity.

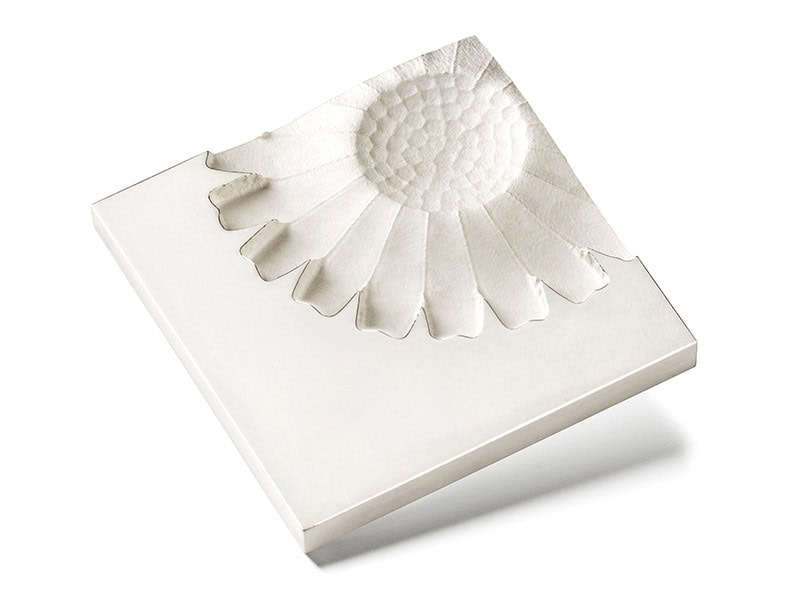

The Daisy brooch, widely owned and mass-produced, reinforces Denmark’s national cohesion. But such symbols can also obscure underlying complexities and contradictions within the national narrative. Notably, this applies to Denmark’s colonial history and the exclusionary aspects of its national identity. Over the past 20 years, Buck has appropriated the daisy motif for several works. His earliest exploration of the daisy motif goes back to 2003. He created a series of three brooches faithfully replicating the Georg Jensen daisy outline and imprint. By doing this, Buck was negotiating notions of ownership when it comes to national emblems and identity construction. Does this specific daisy belong to Georg Jensen, or does it belong to Denmark as a country? As a Danish citizen and subject of the Queen, is Buck allowed to replicate it? Does his nationality and identity bestow him special access to this floral design?

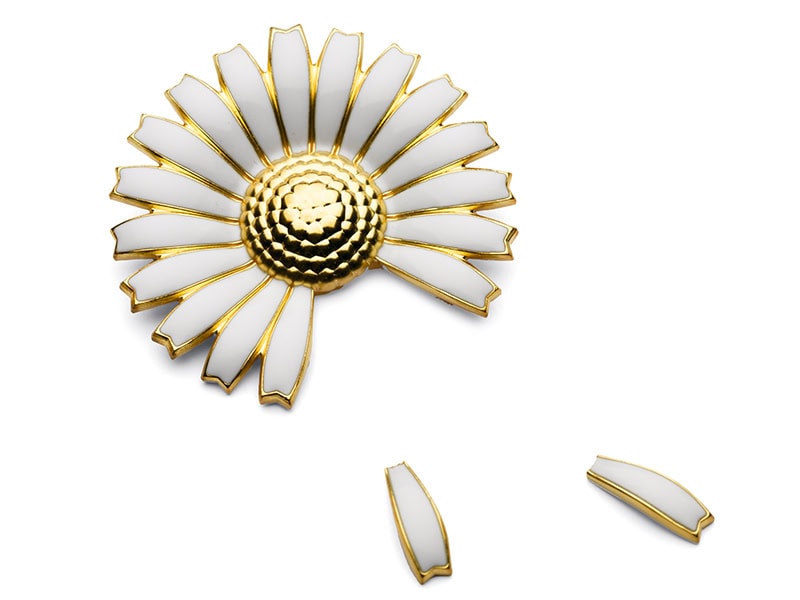

Later, in 2007, Buck escalated this critique. He started using actual Georg Jensen brooches as readymades. One intervention involved stamping his maker’s mark alongside the original brand’s. During the stamping process, some petals fell off. This resulted in the series Loves Me, Loves Me Not. The title, as art historian Jorunn Veiteberg argues, points to “both doubt and ambivalence.”[1] This ambiguity may apply to the brooch as a Georg Jensen product. But it also extends to its symbolic weight as a national emblem and an enduring symbol of the affection Danes feel for their queen. Buck’s intervention thus invites a broader reflection on the ideological underpinnings of Danish identity and loyalty to royal institutions.

To this day, Denmark remains one of the most ethnically homogenous societies in the world. This factor is often credited with fostering the development and perpetuation of a strong, politically stable, and unified nation.[2] But as anthropologist Kusum Gopal argues, this notion of unity translates into a conception of equality that veers toward a preference for “sameness in every respect.”[3] Difference is often met with distrust, whether it relates to cultural background, ambition, or success.[4] It is therefore pertinent to question the Danes’ affection for their queen and their approval of monarchy altogether, which epitomizes elite privilege and unquantifiable wealth.

The Georg Jensen Daisy brooch embodies notions of Danish national identity, as well as the conflation between equality and sameness. The queen wears it. It is also found in most Danish families’ jewelry boxes. In a country that has no official floral emblem, the daisy was even voted Denmark’s unofficial national flower due to its widespread ownership. This contributes to cementing the brooch’s role as an object of national consensus. As an object commemorating Princess Margrethe’s birth, it also functions as a material expression of monarchical reverence. Buck’s appropriation strips the object of its cultural sanctity and reframes it as a commodity. The resulting series, Loves Me, Loves Me Not, provokingly questions the overarching consensus that runs through contemporary Danish society. It challenges not only the monarchy but also the erasure of Denmark’s colonial legacy. By defacing what is arguably the most recognizable symbol of Danish royalty, Buck symbolically confronts the imperial institution that drove a now-dissolved but historically significant colonial empire that has brutally impacted the Caribbean, West Africa, India, and Greenland. These colonial entanglements, often overshadowed by later British Imperialism, remain absent from Danish public discourse and collective memory.[5] Loves Me, Loves Me Not thus embodies Buck’s ambivalence toward Denmark as a nation and the broader culture of denial it sustains.

In Daisy, Freely After Niels Heidenreich (2007), Buck furthers his critique. The series consists of four pendants made by cutting a Georg Jensen Daisy brooch into four parts. The title and the object both point to the infamous theft of the Golden Horns from the Danish royal treasury in 1802 by goldsmith Niels Heidenreich. These Iron Age artefacts were Denmark’s greatest gold treasure. Heidenreich unapologetically melted them into miscellaneous jewelry pieces and poor copies of Indian colonial coins.[6] Buck’s reference to Heidenreich draws a parallel between historical sacrilege and his own transgressive gesture. It questions the legitimacy of altering another designer’s work, but more importantly, an icon of Danish identity. The allusion to the Golden Horns, steeped in romanticized nationalism and imperial nostalgia, underscores how objects can embody symbolic power beyond their material form. Buck’s fragmentation of the Daisy brooch echoes Niels Heidenreich’s vicious act, sacralising the object through violation and solidifying his affront to Danish national identity and patriotism.

Ultimately, Buck challenges the assumption that jewelry must be static, ornamental, and apolitical. Instead, he reimagines it as a dynamic form, capable of being reshaped, reinterpreted, and deployed as a vehicle for political critique. Through humor, he renders his provocations accessible. His use of irony fosters engagement rather than alienation. By appropriating and subverting familiar symbols like the Daisy brooch, Buck invites the public to reassess the values embedded within them. In his hands, a cherished emblem of Danish tradition becomes a tool of resistance and reflection.

Bibliography

Booth, Michael. The Almost Nearly Perfect People: Behind the Myth of the Scandinavian Utopia. New York: Picador, 2016.

Brimnes, Niels. Aarhus University. “The Colonialism of Denmark-Norway and Its Legacies.” nordics.info. Last modified January 7, 2021. https://nordics.info/show/artikel/the-colonialism-of-denmark-norway-and-its-legacies.

Gopal, Kusum. “Janteloven, the Antipathy to Difference: Looking at Danish Ideas of Equality as Sameness.” The Cambridge Journal of Anthropology 24, no. 3 (2004): 64–82.

Veiteberg, Jorunn. The Real Thing: Jewellery and Objects by Kim Buck. Translated by Arlyne Moi. Stuttgart: Arnoldsche Art Publishers, 2021.

We welcome your comments on our publishing, and will publish letters that engage with our articles in a thoughtful and polite manner. Please submit letters to the editor electronically; do so here. The page on which we publish Letters to the Editor is here.

© 2025 Art Jewelry Forum. All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. For reprint permission, contact info (at) artjewelryforum (dot) org

[1] Jorunn Veiteberg, The Real Thing: Jewellery and Objects by Kim Buck (Stuttgart: Arnoldsche, 2021), 78.

[2] Marilena Geugjes, Collective Identity and Integration Policy in Denmark and Sweden (Wiesbaden: Springer, 2021), 13.

[3] Kusum Gopal, “Janteloven, the Antipathy to Difference: Looking at Danish Ideas of Equality as Sameness,” The Cambridge Journal of Anthropology 24, no. 3 (2004): 70.

[4] Michael Booth, The Almost Nearly Perfect People: Behind the Myth of the Scandinavian Utopia (New York: Picador, 2016), 3.

[5] Niels Brimnes, “The Colonialism of Denmark-Norway and Its Legacies,” nordics.info, Aarhus University, last modified January 7, 2021, https://nordics.info/show/artikel/the-colonialism-of-denmark-norway-and-its-legacies.

[6] Veiteberg, The Real Thing, 78.