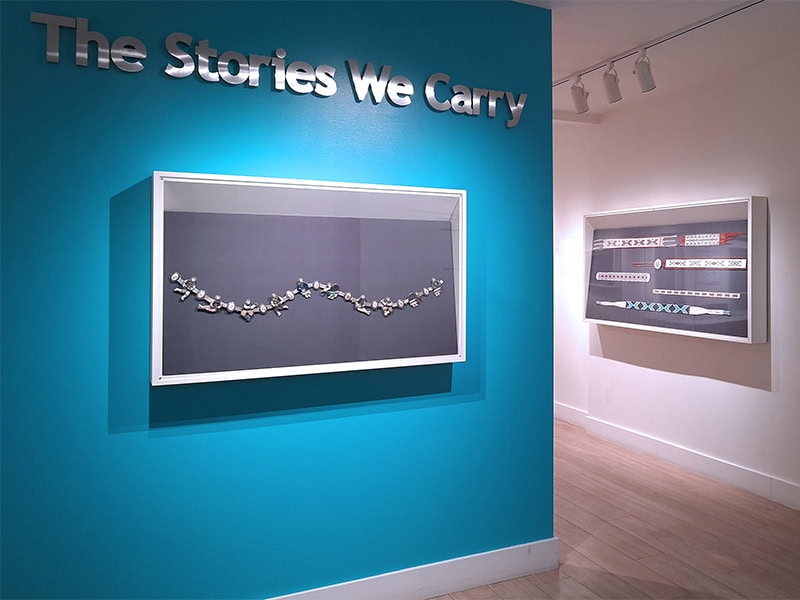

This week, AJF goes to Santa Fe, NM, US. There, the travelers will take in The Stories We Carry, on view at the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA). The exhibition’s curator, Brian Fleetwood (Mvskoke Creek), will give us a special tour of his show.

There isn’t a monolithic “Indigenous jewelry,” states Fleetwood. Each culture and nation brings its own traditions, imagery, themes, materials, etcetera. In other words, there’s Hopi jewelry, and Tlingit jewelry, and Ho-Chunk jewelry, and Mvskoke jewelry, and Oneida jewelry, and hundreds of others. The Stories We Carry highlights more than 100 contemporary Indigenous artists across the permanent collection of the IAIA Museum of Contemporary Native Arts’ (MoCNA). In this interview with Noelle Wiegand, Fleetwood takes us through his curatorial approach, the rich meaning embedded throughout Indigenous craft, and how one might begin their own Indigenous jewelry collection.

The Stories We Carry remains on exhibit through March 21, 2028.

Noelle Wiegand: The Stories We Carry features over 100 Indigenous makers. How did you approach this from a curatorial standpoint? What key factors were you looking for when choosing which works to include?

Brian Fleetwood: First, I’d like to acknowledge the curator of collections at MoCNA, Tatiana Lomahaftewa-Singer. Tatiana contributed a great deal of work and expertise to the development of the exhibition and should be recognized as co-curator. The Stories We Carry wouldn’t have happened without her.

The primary theme of the exhibition is exploring the relationship between Indigenous jewelry and storytelling. The exhibition focuses on artists who have ties to IAIA, with most of the works coming from MoCNA’s permanent collection. We looked at the recent history of Indigenous jewelry and the way that the Institute has acted as a hub for contemporary Native artists, and how the works of the artists presented engage with the purpose and functions of jewelry, particularly from an Indigenous perspective.

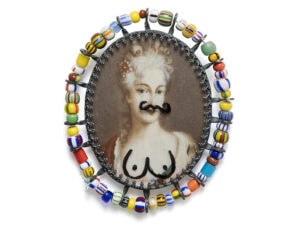

Originally, I had around twice as many selections as eventually made it into the exhibition. I really wanted to get as close as possible to engaging in the full depth and breadth of North American Indigenous jewelry practice with the exhibition, looking at material, process, region, culture, and more. This is an impossible task for a single exhibition, of course, but I have a real interest in pushing back against the preconceptions and generalizations that people tend to have regarding Native culture and art. The selections we settled on were works that I felt were unusual, illustrative, or essential, especially within the show’s premise that jewelry is intimately tied to personal storytelling.

My definition of jewelry is broader than most. Jewelry is, as far as I’m concerned, any adornment or modification of the body for the purpose of expression or the reification of the self. The things we wear and the way we present ourselves are powerful tools for creating and telling our own stories. The jewelry we choose to place on our bodies reminds us of where we come from and who our people are. It communicates to the world our achievements, values, allegiances, and how we would like to be seen. Storytelling is central to so much of Indigenous cultural practice, and jewelry serves as a kind of container for our stories and identity, which allows us to carry them with us, and to rewrite them as desired or necessary. The pieces featured in The Stories We Carry are all works that relate to this idea; jewelry is a vessel for narrative.

What does this collection as a whole say about the IAIA community, its history, and future?

Brian Fleetwood: I’m generally hesitant to speak broadly about anything, and especially Indigenous people and culture, which are so often flattened and generalized by the broader dominant culture. There are over 500 federally recognized tribes in the United States alone, all with specific and unique histories, cosmologies, and cultures. With dozens of tribal nations represented on the IAIA campus at any given time, individual students, staff, and faculty hail from Indigenous cultures that range from North of the Arctic Circle to South America, and even around the world.

I would argue the diversity of cultures, material histories, and traditions of making within the IAIA community is richer than essentially any other institute of higher education in the country. This wealth of perspectives and histories feeds a dynamic, creative atmosphere, where ideas, knowledge, and understanding are shared and traded from individual to individual and culture to culture as students, staff, artists-in-residence, faculty, visitors, and more come to terms with their place in that incredible conjunction of creative and ideological forces. The works in the exhibition reflect this diversity and dynamism.

I tell my students that traditional and contemporary works are not at odds with one another but are essential to one another. Everything we consider traditional was an innovation at some point, and everything we consider contemporary relies on the work and insight of all the people who have come before. The work in the exhibition reflects this diversity of experience, perspective, intent, material, process, and form.

Material processes, community, and storytelling are all pillars throughout Indigenous jewelry. Describe how you approached the layout of the exhibition to communicate these ideas.

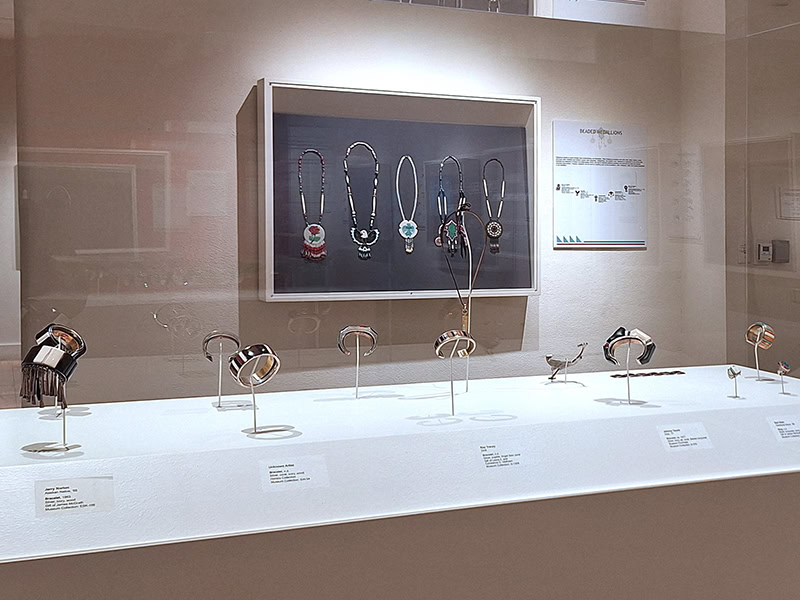

Brian Fleetwood: The exhibition is loosely divided into three rooms that address each of those themes individually.

As one enters the first and largest room, they are greeted by the title wall, mounted with Denise Wallace’s Craftsperson Belt. This segmented belt made of silver, a variety of stones, and walrus ivory, with meticulously constructed figures and scenes, depicting culturally based craft practices, introduces the audience to the first theme: process. This space is dedicated to specific forms and processes common to Indigenous jewelry practice. Cases feature such processes as tufa casting and lapidary. This room also features processes not so closely tied to European metalsmithing practice, like beadwork, and those less commonly associated with Indigenous jewelry—enameling, for example.

The middle room is the smallest and most intimate of the three. This is the community room and focuses on the IAIA community in particular. This space contains the work of past faculty, including a couple of unconventional Charles Loloma pieces. Also featured here are the works of a number of former artists in residence, each engaging in thoughtful, bitingly contemporary work that is nonetheless deeply connected to historical cultural practice. The artists featured include Wayne Nez Gaussoin, Jodi Webster, Kenneth Johnson, and Kevin Pourier. However, the real focus of this room is a large floor case with the work of current and recent students. These young jewelers are working with a diverse set of materials, themes, forms, and processes, and it is exciting and humbling to be able to work with them. Some standout works include those by Carly Feddersen, Jerome Nakagawa, Jeremy Red Eagle, and Jaycee Custer.

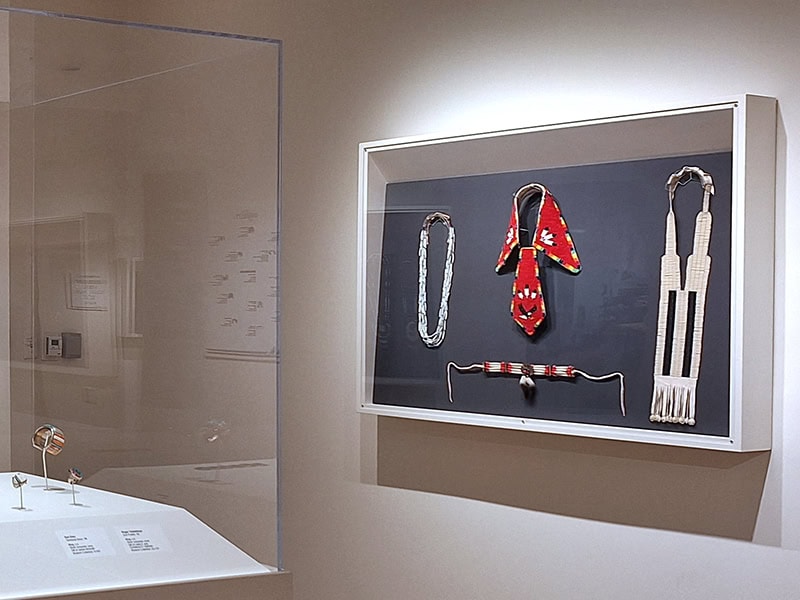

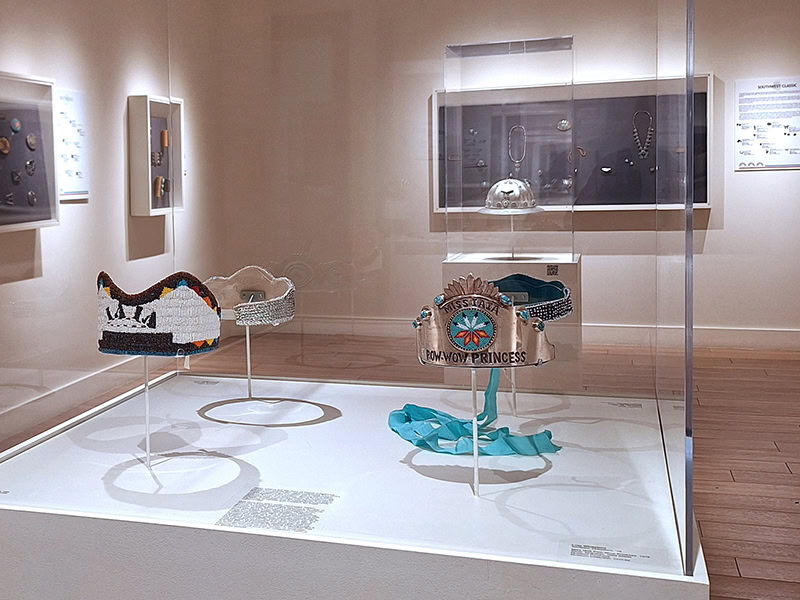

The final room focuses on storytelling, and it contains cases that each focus on regionally or culturally specific work, such as that made in the Southwest, Northwest Coast, and by members of the Native American Church, as well as work that serves certain cultural functions, such as crowns for Native pageant royalty, cowboy/Western culture, and conceptual and political work.

Landscape or relation to the land is a critical theme throughout Indigenous jewelry, but it is not always depicted via a picturesque landscape. Give us an example of a piece in the exhibition that showcases landscape in a more abstract manner.

Brian Fleetwood: Relationships with the land are a fundamental component of Indigenous culture, broadly speaking, and recognizing and honoring those relationships is central to much Indigenous cultural practice. Works do sometimes depict literal landscapes, but much more often this relationship to the land is reflected in the choosing and handling of materials.

Indigenous cultures often conceptualize the land itself as a body, often one of which we humans are literally a constituent part, with agency and rights just the same as any body—not simply place, but being.

Nicholas Begay, a Navajo artist and IAIA alum, has a number of works in the exhibition that comment on mining practices on his people’s reservation. Among these are repousséd and chased copper pieces that mimic the contours of strip mines. Though beautifully made, these pieces, when worn on the body, look almost like wounds.

Are there any pieces in the exhibition that have received a surprising or controversial response from attendees?

Brian Fleetwood: I’m not aware of any particular controversies, and I’m pretty tough to surprise, but I have enjoyed the responses to Indian Chief Headdress, by Richard Glazar Dinay. This piece is an aluminum hard hat embellished with, among other things, buffalo nickels and a Bureau of Indian Affairs Police badge. People seem somewhat bemused at its inclusion in a jewelry show. This reaction is a fantastic opportunity to talk about the backstory of this piece, the reaction to which is often very fun to watch as well. In a tongue-in-cheek reference to tribal police, Glazar, who is Mohawk, seems to be using the hard hat as an allusion to his people’s reputation as ironworkers. Called “skywalkers,” these Indigenous metalworkers are considered among the most skilled in the world and are responsible for huge swaths of North America’s most famous skylines.

What does the public commonly misunderstand about Indigenous jewelry? How would you respond to that misconception?

Brian Fleetwood: The biggest misconception I encounter is a reductive view of what constitutes Indigenous jewelry, although this is true of Indigenous arts and culture more broadly. It’s important to recognize that there isn’t a monolithic “Indigenous jewelry.” Rather, there’s Hopi jewelry, and Tlingit jewelry, and Ho-Chunk jewelry, and Mvskoke jewelry, and Oneida jewelry, and literally hundreds more. Each culture and nation has its own traditions, imagery, themes, material inclinations, and so forth. Recognizing this diversity and complexity is frankly a moral necessity, but it also makes for a richer understanding of Native jewelry, as well as art and culture more broadly.

What makes a piece of jewelry exceptional, and where should one start if they were to begin collecting Indigenous jewelry?

Brian Fleetwood: What makes anything exceptional is such a broad and difficult question. I suppose it depends on the work, but demonstrations of technical skill, design or storytelling acumen, or innovations in material, process, and technology are all indicators of work worth noting.

I would encourage folks interested in collecting Indigenous jewelry to first see if there is a tribal museum or cultural center near where they live. They are more common across North America than you might think. These often have exhibitions or shops that feature the works of tribal members, and staff are typically very knowledgeable and enthusiastic about talking about this kind of work.

The Native art market circuit would be my next suggestion. The most famous of these is Santa Fe Indian Market, organized by the Southwestern Association for Indian Arts, though there are many more across the US, including Mvskoke Art Market, the Heard, the Autry, Eiteljorg, and a great deal more. These are a fabulous way to see a diverse array of artists from a number of tribal nations, as well as to meet and talk to the artists themselves.

Lastly, do your research and collect what you love. Ultimately the jewelry you collect and adorn yourself with is a part of your story, and that’s your story to tell. Who am I to say how you should tell it?

Are you seeing any common trends in emerging Indigenous artists?

Brian Fleetwood: I see lots of trends, but few common ones. Emerging Indigenous jewelry artists are bearing their respective cultures into the future and tending their own personal practices alongside. The diversity and disparity of the multitude of cultures informing these jewelers’ work makes it very difficult to pin down commonalities.

I make no claims as to what Indigenous jewelry will look like in 15 years, or 30, or five. But I am very excited to be surprised.

Can you please share with our readers any discoveries that you have recently made pertaining to Indigenous jewelry art?

Brian Fleetwood: I don’t know how comfortable I am with the framing of discoveries, but I have been doing quite a bit of research on bolo ties in the last couple of years. I think they are underrated and maybe a bit maligned in some circles, but they seem to be having a bit of a cultural renaissance in the US and beyond. The history of the cultures, subcultures, and countercultures who have adopted it as a part of their dress is absolutely fascinating. I worked on (along with my co-curators Ana Lopez and Hannah Toussaint) a traveling exhibition informed by some of this research called Everybody’s Bolos. It is currently at Fuller Craft Museum, in Brockton, MA, US, through June 8, 2025, and will be on view at the gallery Hecho a Mano, in Santa Fe, NM, the summer of 2025.

We welcome your comments on our publishing, and will publish letters that engage with our articles in a thoughtful and polite manner. Please submit letters to the editor electronically; do so here. The page on which we publish Letters to the Editor is here.

© 2025 Art Jewelry Forum. All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. For reprint permission, contact info (at) artjewelryforum (dot) org