I am sitting at the table in the shared office at Objectspace where all the staff sit together in one open room that infamously has no natural light. The architects who refurbished the 1980s industrial unit that we call home gave the building a striking steel and light façade. It is the singular architectural feature of the gallery, but its cost was the windows it covered in its design. The staff endure the office lighting with varying degrees of animosity, and on a day like today, a beautiful summer late-afternoon in early February, I wouldn’t know if it is still light outside.

To my left, at the end of the large worktable are some make-shift trestle tables, covered in the remnants of weeks spent crating hundreds of pieces of Warwick Freeman jewelry to ship to Munich for his survey exhibition. There are Tyvek scraps all over the floor, bags of rubbish, hot glue guns, and a large container filled with countless different versions of the packing list.

In the hectic flurry of the last six weeks, I have thought often of the momentous scale shift between Objectspace and the Die Neue Sammlung – The Design Museum at Pinakothek der Moderne in Munich. Objectspace is small. When the gallery started 20 years ago, it was very small. It began with one staff member in one room and bit-by-bit the gallery has grown. Warwick Freeman was part of the group of people who created Objectspace. It was to be the first and only public gallery in Aotearoa New Zealand dedicated to craft and design, and it still is today. We don’t have a collection and we don’t sell work. We exist to make exhibitions, publications, and events. Now nine staff run our Auckland gallery, with three more in our little satellite space in Christchurch, in the South Island of New Zealand. Warwick was the first chairman of the Objectspace board and there has only been one more since him. I too am only the second director the gallery has ever had.

Warwick could have picked a much larger institution than us to be his New Zealand partner for his retrospective. Our national museum Te Papa Tongarewa, in Wellington, holds the largest collection of his works, some of which are in this exhibition, and there are others, too, who showed interest. They likely could have offered more money, and they definitely would have provided staff with the experience and expertise (and actual conservation departments) to send a complex exhibition to the other side of the world. But Warwick never entertained it, he wanted Objectspace to do the job.

The detritus of the crating is very fresh. The crates have only recently been collected, and I cannot bring myself to clean it up. Seventy-two hours before the work’s departure, we jumped through a series of last-minute customs requirements. The Latin genus and species needed to be added to every relevant item in the packing list. Warwick’s materials list spans six decades and well over 500 individual objects. All told, it is a vast and incongruous map of the natural world that centers around the geography and biology of Aotearoa New Zealand, but also leaps out into the Pacific and much further afield. There is of course the multitude of minerals—scoria, basalt, argillite, jasper, greenstone, lapis lazuli—but it’s the animals where it gets tricky. Materials like turtle shell and whale bone can’t easily be moved across borders. For Warwick, compiling the details needed for freight required an impossible process of remembering—trying to locate 40-year-old sources for where a piece of shell or bone might have come from. There was a seed from Fiji and a beautiful lustrous black shell indigenous to the Philippines that eluded us for days.

There are a few works that haven’t made it to Munich due to their insurmountable customs challenges. Dead Set is one of these. First made across a three-year span (2003–2006), it consists of 121 silver-capped pendants made from animal parts, Warwick installs the work in an imposing 46-inch (1200 mm) wide circle. He collected the animal parts from up and down Aotearoa New Zealand, some picked up off the side of the road or from along our coastlines. The work documents an array of indigenous and introduced animal species as well as parts from the only two animals in Aotearoa New Zealand that provide any threat to humans: the wild pig’s tusk and the shark’s tooth.

Just last week I was in Warwick’s studio and pulled open a drawer to find the head of a gannet and an albatross foot. Both sent to him by a friend, they are waiting for the next Dead Set edition.

Perhaps it’s unhelpful to write about Warwick’s exhibition with a work that won’t be seen, but his use of materials is bound up so tightly with his jewelry identity. In curating the show for an international audience on the other side of the world, we have talked about this often. How does Warwick tell his story without it being misunderstood? How does it remain his jewelry story, and not get swept up into a broader, all-encompassing tale of New Zealand-ness?

When we first began working on this exhibition, my colleague Bronwyn Lloyd (co-curator with myself and Petra Hölscher, at Die Neue Sammlung), spent 10 hours a week archiving Warwick’s practice. It would take more than two years to complete. Frustratingly for Bronwyn, Warwick’s one stipulation was that she organize the archive alphabetically by title of work. This system (which was abandoned very quickly) brought with it a jumbling disorganization of date, material, or form. Warwick’s point was that a chronology neither interested him nor felt like a useful reflection of how he works.

There are some periods in Warwick’s work that are particularly time stamped, that you could look at and quite accurately pick when they were made, but for the most part the more striking recognition is how much of his work resists dating. The narrative arc of a retrospective exhibition told chronologically is certainly compelling. It tidies things up, draws works together, and proclaims that things are all connected in an orderly line. But Warwick describes this as having “all your work ending up behind you.” Where, then, do you go next? Instead, if you look closely across five decades of work, he returns with striking consistency to a palette of materials, signs, and symbols. Because he works in editions, the forms he began making in one decade may well reappear 30 years later.

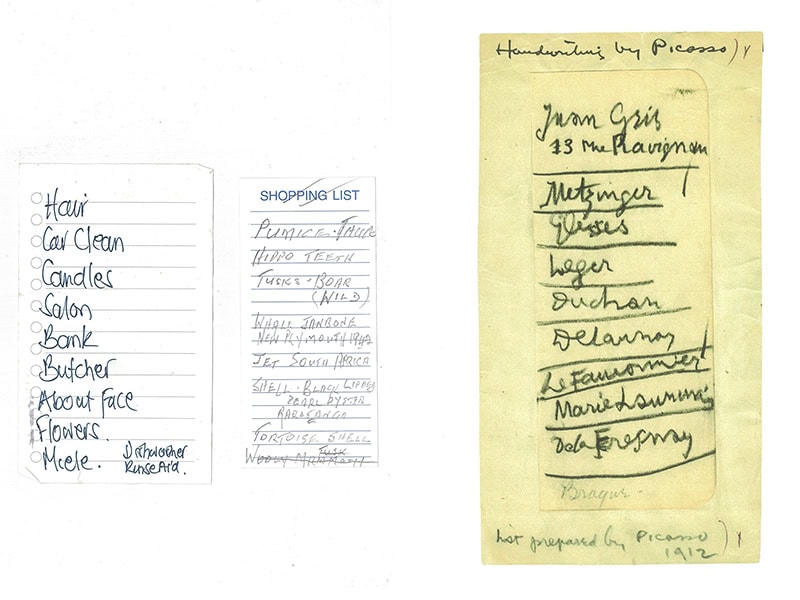

When you walk into the exhibition space on the second floor of the Pinakothek‘s rotunda you will see a tall list of words, 24 in total. This list has become the exhibition’s organizing structure. Twenty-four emblematic groups. Each one articulates an aspect of Warwick’s archive that is an enduring or useful way to see his work. This word poem isn’t at all new. Warwick has long played with language. There is a folder named Lists in his paper archive, with copies and originals of lists, some collected and some his own. There is a to-do list, perhaps picked up off the ground: “Hair, Car Clean, Candles, Salon…,” beside a material list of his own, “Pumice, Hippo teeth, Tusk…” The next list is a copy; written in graphite and dated 1912 it belongs to Picasso and famously lists his artist commendations for the first international exhibition of modern art in the United States.

Over the course of three years of working with Warwick in preparation for this exhibition, we have come to understand his jewelry best as a language he is building. A vocabulary of forms that are open to being read, with suites of emblems sometimes brought together into what he calls “sentences.” We have built the exhibition around this idea; you can feel it in the name of the exhibition: Hook Hand Heart Star.

For the exhibition Warwick has created four new sentences of work. He first made a sentence called Insignia in 1997, which appears in this exhibition. It draws together a sequence of six brooches. The work reads (from left to right): a sandstone and quartz Shield; a jasper Red Spot; a greenstone Karaka Leaf; a pearl-shell Eye; a turtle-shell Bird; and a tilted Skull made of cow bone. Together, the works look like glyphs.

The four new sentences are longer than Insignia and other sentences in Warwick’s archive. They punctuate four equal points of the Pinakothek’s rotunda. Bringing his works into these linear groupings, Warwick invites the viewer to draw their own meaning. It is a very different experience from looking at a single piece of jewelry. An emblem like a heart or star may be universal, but others are recognizable only within the bounds of its country or as a niche cultural reference.

I have watched people read Warwick’s sentences in front of him. They are always hoping he will unlock its secret message, but his curation isn’t literal. The arrangement could be motivated by a visual or verbal sensibility or material. He sometimes describes this as “what looks right.” It is an intuition we all possess about things that belong together.

Several months ago, we were mocking up case layouts. Watching Warwick assemble each of the 24 groups into arrangements was confounding. Every approach he made to composition and layout I couldn’t have predicted, and I never could have emulated. Besides his sentences, there were very few linear formations. He would draw two works together and push others away at a distant angle, and he would let works drift and shift across the cabinets. It felt like a true expression of the intimacy between the maker and their work. Warwick knows what looks right.

A persistent knotty challenge for this project has been its exhibition design. It is no small thing to ask jewelry, with its handheld scale, to hold its own within the Pinakothek’s second floor gallery, with its natural light ceiling, towering walls, and circular floor plan. We have pushed around ideas that feel torn between what’s right for the jewelry and what’s right for the architecture. But in the last couple of months, we have found a way through, arriving at a conceptual loop that circles (quite literally) Warwick’s entire career.

In 1982 Hermann Jünger, then professor at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, visited New Zealand as a guest of the Goethe-Institut. Warwick, along with other jewelers, took part in a week-long workshop he led. Petra Hölscher writes about this visit in the book Hook Hand Heart Star as a turning point for some New Zealand jewelers, with Jünger inspiring critical ways of developing ideas and pushing jewelry further. Warwick describes the impact of meeting Jünger as less about what happened in the workshop. Rather it was experiencing the seriousness with which Jünger approached the work—it was seeing the difference between “jewellery maker and artist,” as Warwick puts it.

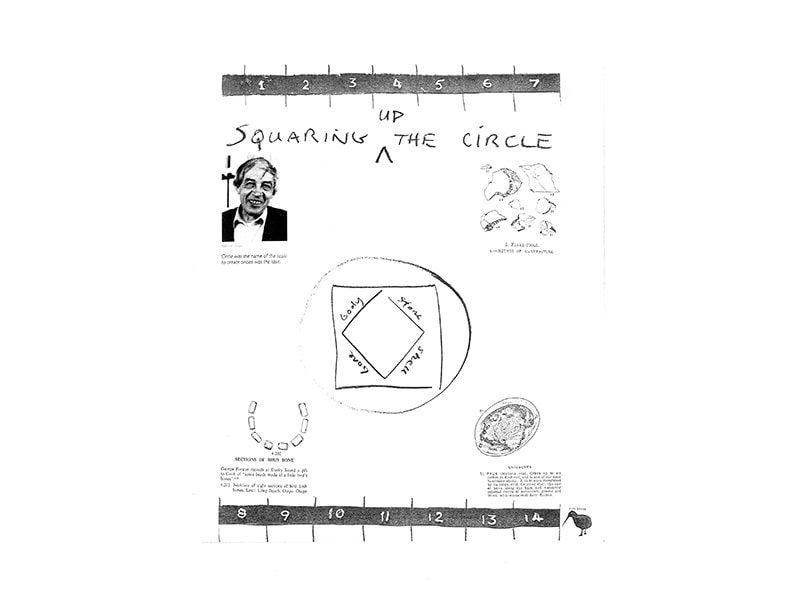

For one of the workshop assignments, Jünger invited participants to simply consider the circle. Six years later, Freeman’s drawing Squaring up the Circle (which includes an acknowledgment to Jünger) was the precursor to three seminal works that featured in the 1988 touring exhibition Bone Stone Shell. The exhibition formalized a decade’s worth of examination by jewelers of materials sourced from the natural environment, and has come to be understood as the most significant contemporary movement for the New Zealand jewelry field. The drawing can be found in the Hook Hand Heart Star catalog and within the exhibition space.

For Hook Hand Heart Star we are revisiting the squaring of the circle inspired by that 40-year-old connection. It is a simple execution that traces a line between Aotearoa New Zealand and Munich, marking two points in Warwick’s career and the work that has been done between them.

Just last week Warwick commented in passing that he is surprised by some of the choices we ended up making for the exhibition and book. Attention is paid to some lesser-known work, and some of his best can only be found amidst the density of his Sentences. Perhaps this reflects the outcome of avoiding chronology. The story to be found in this exhibition will not signpost to the viewer the best, the most iconic, or the most important of Warwick’s work. Instead, it draws a life’s worth of work together as a living breathing thing and asks you to see the myriad connections that are still firing.

It’s up to the viewer how they navigate their way through Warwick’s word poem. It seems to me a generous and open thing that he has allowed the exhibition to develop as a conversation. He has weighed his own beliefs about his jewelry with all of ours. He knows these works cannot ever entirely exist in the vacuum of their own making. There is a quote drawn from Warwick’s archives that I use on the very last pages of my essay for the book that accompanies the exhibition, and again I’ll use it here:

I have had a working lifetime of seeing my work co-opted into people’s lives. Badly worn—occasionally upside down. Whatever my precious conceptual imagination had intended for it—whatever the intended narrative I had attached to it, the owner often has other plans. Rather than feel bruised or abused mostly I get to feel the love.

We welcome your comments on our publishing, and will publish letters that engage with our articles in a thoughtful and polite manner. Please submit letters to the editor electronically; do so here.

© 2025 Art Jewelry Forum. All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. For reprint permission, contact info (at) artjewelryforum (dot) org