- Yaksh Verma is a multi- or “non-disciplinary” artist living in Chennai, India

- He trained as a jewelry designer at Le Arti Orafe in Italy

- His Unspoken-1 series of 25 rings showed at Portugal’s Galeria Reverso, April 25–May 20, 2023, as a duo exhibition (Terhi Tolvanen was the other artist)

Anvita Jain as Project Bawra: Tell us about your background and training as a goldsmith.

Yaksh Verma: I grew up in Amritsar (Punjab, India) in a family of jewelers who migrated from Peshawar (now Pakistan), during the partition of British India in 1947. When I was 19, I was sent to my uncle’s jewelry factory in Amritsar for training as a goldsmith. The sudden demise of my father, and being the eldest among my siblings, led me to take over the crumbling jewelry business. At 21, I moved to Chennai, a gold-jewelry hub, to run a jewelry-manufacturing facility in collaboration with a renowned local jeweler. But my design craving took me to Le Arti Orafe, where I got my first introduction to the world of art. Later, a project to design a Belgian art magazine (which never took off) triggered my artistic approach.

You call yourself a “non-disciplinary” artist and don’t stick to making only jewelry. Can you elaborate?

Yaksh Verma: “Non-disciplinary” comes from my rebellious nature. The main thing that attracted me to art was the freedom to create what I visualize. After considering various terms—mixed-media, multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary, transdisciplinary—I didn’t see a reason to choose any, when the idea was to be free.

At Le Arti Orafe, I basically learned to translate my ideas from paper into a three-dimensional form. I felt ready to create anything: sculpture, architecture, jewelry, furniture … The soul is in the concept. The difference between a large-size sculpture and jewelry is only the scale.

Tell us about the Unspoken series. How did it come about?

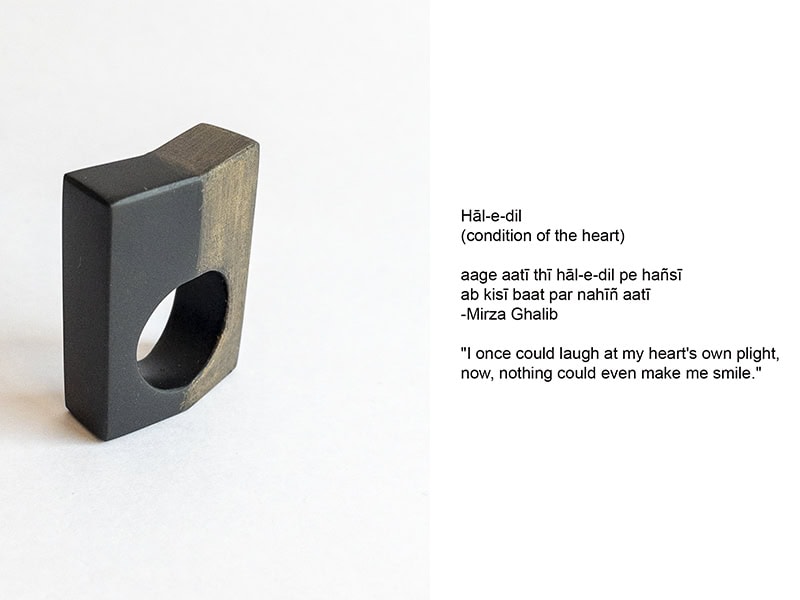

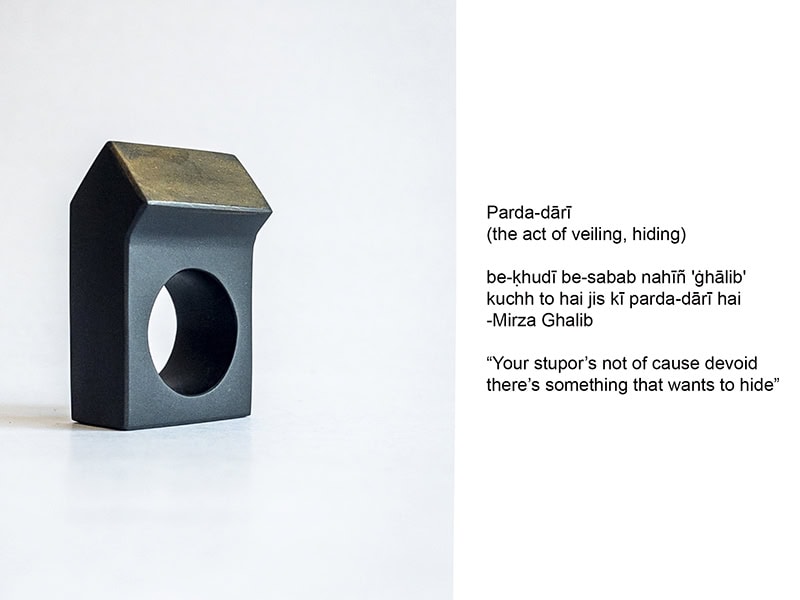

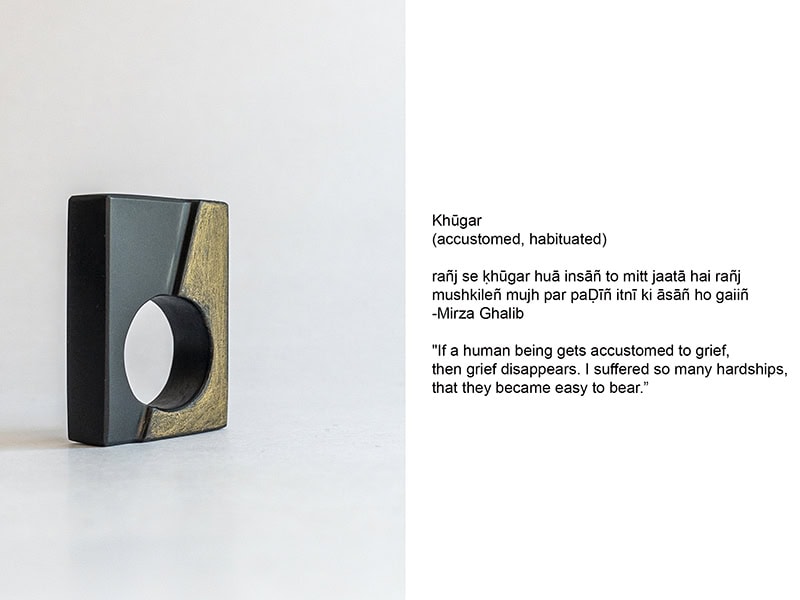

Yaksh Verma: I made a series of rings with Kasauti (a Hindi word for touchstone, a black stone used to test the purity of gold). The rings were sculpted using a monolithic technique. [I drew] on the surface with gold by rubbing and scratching. This silent process requires a good amount of force, pressure, and control. The physical actions would lead to a surge of emotions. While training as a goldsmith, I clearly remember rubbing the gold rods and quietly sharing my innermost thoughts with the stones. I am keen to explore how and why to express the hidden storm behind the silence. As Mirza Ghalib said in one of his poems:

be-ḳhudī be-sabab nahīñ ‘ġhālib’

kuchh to hai jis kī parda-dārī hai

—Mirza Ghalib

“Your stupor’s not of cause devoid

there’s something that wants to hide”

Are the pieces “designed,” or spontaneous expression? Would you say the process of making, specifically the rubbing, was therapeutic?

Yaksh Verma: I’d say they are spontaneously designed. The process transported me to the past, bringing back a lot of hidden memories. Often, during the rubbing process, there was an emotional outpour.

The works are minimalist and architectural. The pieces are ornaments but not ornamented. Minimalism is more of an exception than the rule in India. Do you see this changing? You’re also turning the hierarchy of materials on its head. Do you find it overwhelming to challenge the norm, especially in the context of jewelry in India?

Yaksh Verma: Well, minimalism is not a trend. It’s an attitude and a choice. I personally go in the open fields and look up in the sky to find minimalism in India. When it comes to aesthetics, I feel I am never “Indian.”

Yes, I find it very overwhelming to challenge the norm. I like to object and reject. Except for the temple jewelry from South India, I don’t like ornamental design, though that’s what I was trained to make.

The titles of all the works are taken from Mirza Ghalib’s poems/ghazals. Alongside the works, links to listen to these poems were made available to the viewers in the gallery. In a way, you’ve reduced the works visually but used poetry as a verbal ornament to enhance their meaning and experience. What’s your relationship to poetry?

Yaksh Verma: That’s an interesting perspective on poetry. I think my love for Urdu poetry, ghazals, and nazams comes from my roots in Peshawar and Kabul. A TV series about Mirza Ghalib, directed by Gulzar [an Indian Urdu poet, lyricist, author, screenwriter, and film director known for his works in Hindi cinema], made me fall in love with Ghalib’s poetry.

How was the exhibition conceived and received? Can you talk a bit about the interactive aspect of the show?

Yaksh Verma: I wrote an email to Paula Crespo, the owner of Galeria Reverso, which she read after a year or so and sent me a message on my mobile. In response, I remember I wrote a short poem. And she said, “Oh, so you are a poet and a philosopher, I hope you don’t suffer much.” And I replied, “One cannot become a good poet or a philosopher without suffering.” Then I sent her flowers and we started to talk about this project.

To encourage maximum possible interaction between the public and the work, touchstone and a piece of gold were placed in the gallery, inviting visitors to engage in the same “therapeutic” act of rubbing/drawing. There was a lot of curiosity and interest to scratch the stone.

Paula had to urgently make the scratching device herself, based on a picture I sent her. This item would be too complicated to send through customs from India because of the piece of real gold. [Find more information about this exhibition here. —Ed.]

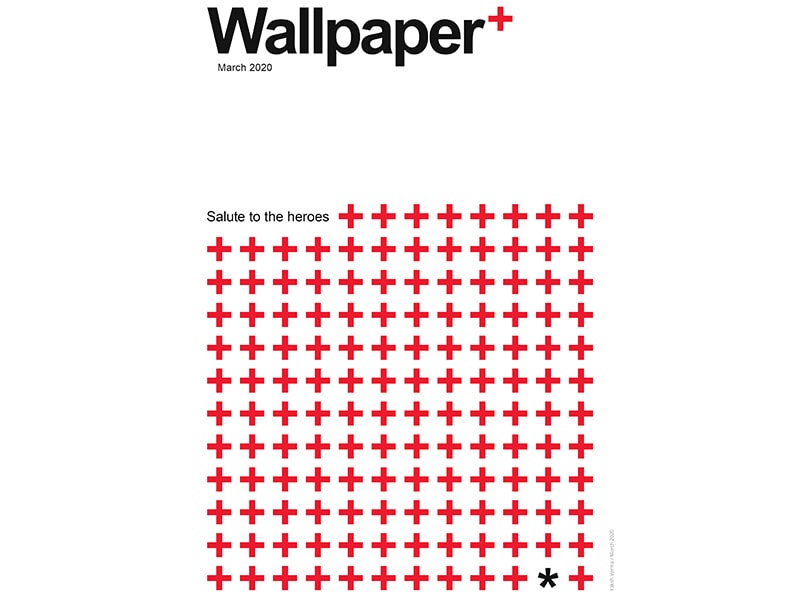

Your design for Wallpaper* magazine’s poster competition was selected among the 50 best. Can you share some of your other works? What projects are you currently working on?

Yaksh Verma: A significant focus is on a series of sculptural/installation works exploring human experiences of resilience and hope amidst adversity and war. One of these uses the Kasauti/touchstone on a larger scale. Alongside my romantic ideas of forms and concepts, I’m eager to explore the intersections of art, activism, and social commentary. For another very exciting project, we’re converting an existing arms manufacturing facility into a toy factory.

The art/design scene in India is booming. What do you think about the future of art jewelry in India?

Yaksh Verma: Conceptual art requires viewers to engage with complex ideas, symbolism, and unconventional mediums or techniques. The traditional mindset often favors forms passed down through generations. The Indian jewelry market is dominated by gold and diamonds as valuable investments and status symbols. Art jewelry, which emphasizes artistic expression over material value, may face challenges in finding its place. To promote its value as wearable art, there is a strong need for education, dedicated galleries, and awareness-building initiatives to bridge the gap.

Which artists do you consider a strong point of reference?

Yaksh Verma: Edmund de Waal, Donald Judd, John Pawson, Richard Serra, Dani Karavan, Tony Smith, Christo.

Thank you so much for your answers and your time.

Yaksh Verma: It was a pleasure to engage in this conversation with you.

We welcome your comments on our publishing, and will publish letters that engage with our articles in a thoughtful and polite manner. Please submit letters to the editor electronically; do so here.

© 2024 Art Jewelry Forum. All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. For reprint permission, contact info (at) artjewelryforum (dot) org