- Mahnaz Ispahani Bartos has roots in Persia and South Asia, where she was raised. There, jewelry is interwoven into every life ritual

- Her gallery, Mahnaz Collection, specializes in original jewelry made by transformational, independent jewelers active from the mid-20th century to the present

- The gallerist also feels a deep connection to the American Southwest and is drawn to the work of Native American jewelry artists

Olivia Shih: During your childhood, you sincerely appreciated jewelry, especially since your family gifted it as a gesture of love. Tell us more about your early relationship with jewelry.

Mahnaz Ispahani Bartos: Many families gift jewelry to their daughters out of love, but they also do so because often jewelry is usually a woman’s only financial asset.

I learned early how meaningful jewelry can be. When I was about seven, living in Chittagong, a port city in what was then called East Pakistan, my Bombay (Mumbai)-born, Iranian-origin grandmother gifted me two Burma ruby, diamond, and turquoise pendants in star and paisley designs, as well as a pair of delicate emerald bead and seed pearl hoops. I couldn’t wear them myself until I got older, so I displayed the hoops on the ears of my favorite doll. During the revolution of 1971 that turned East Pakistan into the new nation of Bangladesh, and the accompanying war that broke out between Pakistan and India, the Indian Navy sank the ship carrying all our possessions—my doll and my grandmother’s earrings ended up at the bottom of the Indian Ocean. Those buried jewels memorialize the terrible times we lived through.

My other grandmother, an Iranian sophisticate, taught me about my Persian heritage and gave me sky-blue Nishapur-quality Persian turquoise jewels. She imbued me with a love for the beauty of turquoise and its protective and healing qualities. Turquoise has been long and widely used: in Persia and ancient Egypt, among the Aztecs, and among the Anasazi people who inhabited the southwestern US from about 350 BC. I am a devotee.

My mother, born into an old-world Lucknow, India, family, was unusual in her time and place: a cosmopolitan intellectual, a patron of young and women artists, she was genuinely avant-garde. She mixed my father’s gifts of Tiffany diamonds and fine Swat emeralds with huge Mexican costume earrings she bought herself when visiting the 1964 World’s Fair. When I was barely a teenager, her gift was a trendy, single-stone 18-karat gold and cabochon cat’s-eye signet ring—a somewhat nontraditional girl’s gift in 1970s Dhaka.

I moved homes after the war to live in Karachi, Pakistan. I elected to have my nose pierced when I was 13. Later, traveling back to Karachi from the US, my friends and I would treat ourselves to a visit to our favorite jeweler. We endlessly discussed the details of the design of a new jewel while chatting over cups of dark-brewed tea. I still own the fiery red enamel and 22-karat gold bangles that emerged from several such visits. In those years, I loved stacking silver bangles. I wore about 100 of them on my right arm for several years. I finally had them cut off; the arm had visibly shrunk.

London was the home base for my mother for much of the 1970s and 1980s, so the fashion styles there influenced my youth look. Women wore swinging sautoirs and jewelry made of yellow gold and colored stones inspired by the Beatles’s visit to India. Peace and zodiac sign pendants were omnipresent. Later, costume jewelry was all the rage. I wore the original Kenzo jumpsuits—with an Andrew Grima for Omega watch given to me by my mother.

With a PhD in international relations and a BA in the liberal arts, you built a career in international security policy and professional philanthropy over 25-plus years. Why did you decide to launch Mahnaz Collection?

Mahnaz Ispahani Bartos: It’s complicated. When I started Mahnaz Collection, one of my sisters asked, “What took you so long?” Those who had only known me professionally thought I had taken leave of my senses. My history and family compelled me to pursue foreign affairs and national security service professions, as I saw them. We had suffered through the two bloodiest revolutions of the 20th century, in Bangladesh in 1971 and in Iran in 1979. I had a duty to contribute to studies of why wars occur, which weapons, identities, ideologies, and geographies matter most, and to help influence policies that avoid violence, resolve wars, and protect lives, i.e., that generate greater peace and well-being than harm. Then late in life, I had a daughter. She got me thinking somewhat differently.

When she was young the Afghan war was still in high gear, and the dark cloud of ISIS had appeared. At the Council on Foreign Relations, these were my concerns. At home, however, I longed to set those aside and show my child another side of human nature—the one passionate about creating expressive art, joy in making, and the beauty of being part of communities that created rather than destroyed cultural legacies.

The catalyst for the career change was the shattering of my diamond engagement ring. This loss meant that my husband and I visited dozens of jewelers in New York and across Europe to find a replacement. I looked at more jewelry than I had in decades. And I learned that you cannot replace an engagement ring. I was, however, reconnected to jewelry, to a joyful art, and decided to start Mahnaz Collection. We are celebrating our 10th anniversary this year.

What challenges did you encounter in the jewelry industry as a woman of color? Do you still face those obstacles today?

Mahnaz Ispahani Bartos: I was born and raised in a male-centric, super-stratified brown society formerly colonized by the British. I am familiar with prejudice and policies based on race, religion, caste, gender, class, and colonial hierarchies. While color is an essential basis for many of us, it is not always the sole signifier for everyone. In America, too, the discourse is different than elsewhere.

When I went to work as a professional in the US foreign policy and national security field, I faced obstacles, but I also had allies, male and female. Armed with my PhD, I entered a field comprised almost entirely of white men. There were almost no other “trifectas”—immigrant women of color—in my field’s tiny cohort of women in 1980. I had to insist upon being taken seriously.

People prioritize their multiple biases and prejudices differently at different times. Since March 2020, I have been disabled. As a survivor of extreme COVID, I am attached to an oxygen machine to breathe. It took me years to walk again. I see the world differently now.

I learned some time ago to speak my mind and hold my ground. I sit on boards, chair meetings, and build my gallery as best I can today. Mahnaz Collection is woman-founded, woman-managed, with a diverse all-woman team from different countries and backgrounds.

I was ready for the jewelry industry. The diamond, antique, vintage, and estate-jewelry business could be more hospitable to women dealers of all colors. It is a capital-intensive, still largely family-based world. Barriers to entry are high. Personal trust networks operate. Independent women dealers/owners do operate but mainly on a smaller scale, and the truly successful ones are a tiny minority. Jewelry dealers or gallerists who are women and of color are rare. As such, we have a special responsibility to lead differently. Beyond selling the branded fine jewelry now owned by large corporations, we must support the best work among independent jewelers, jewelers lost to history, and transformative indigenous makers. At Mahnaz Collection we always try to do some of these things.

Mahnaz Collection is best known for its jewelry collection from the 1960s and 1970s. What is it about jewelry from those decades that fascinates you?

Mahnaz Ispahani Bartos: The late 1960s and 1970s have yet to recede as important style influencers, whether in jewelry or fashion, art or architecture. Brutalism was introduced as the new architectural style in Britain in the late 1950s and it is seeing a resurgence of interest today. Pop Art also emerged in the late 1950s and flourished in the 1960s. High and low cultures began a long overdue conversation. The space age began.

Women went to work in vastly larger numbers. They started to wear pants. My mother was one of them. They asked for a different kind of jewelry. So, jewelry changed—earrings became day-to-night, swingier, and more casual, using a palette of more affordable hardstones, Indian carved gemstones, and yellow gold. This is not only aesthetically pleasing but historically important jewelry, and highly collectible.

New jewelry designers emerged in this era. Emigré jewelers, fleeing the devastation of the Nazis, settled in London. Many worked in Hatton Garden, London’s equivalent of New York’s jewelry district. They joined London artists like Wendy Ramshaw and David Watkins, the flamboyant American-Brit Charles de Temple (who designed the wedding ring for the James Bond films), and their elegant leader, Andrew Grima, to create a new avant-garde jewelry design movement. It sought to align with the radical new contemporary art and architecture movements. The experiments the jewelers undertook—texturing rich yellow gold, leaving stones in an almost natural crystal state, using paper, found objects, and hardstones, and creating bold organic and architectural designs—altered notions of what jewelry could be.

If you are interested, I wrote a long essay in our London Originals catalog about this fecund time in modern British jewelry Excitingly, we have two new catalogs and two exhibitions scheduled for the 2023–2024 Fall/Winter season, one on modernist jewelry in Brazil and one on artist jewelers in Italy.

In 2018, your gallery held the exhibition Material Beauty: Modern Hopi, Navajo, and Pueblo Artist Jewelers and published an accompanying catalog. What draws you to jewelry made by Indigenous artist jewelers?

Mahnaz Ispahani Bartos: Influential, diverse forms of modernism emerged in the Southwestern United States led by the Hopi ceramicist, artist, and master jeweler Charles Loloma. These artists dreamed up entirely original compositions based on their otherworldly landscape and ancient motifs, yet employed new forms, metals, gems, textures, and techniques to create jewelry different from anything that had come before. Loloma’s legacy is evident in the work of several successive generations of jewelers. How could this work not excite me? Its radical beauty is undeniable.

What draws me to Indigenous jewelry today is the diversity of work being pursued alongside the continued incorporation of elements of historical culture in jewels. The work of the revivalists, the modernists, and the techno-transformationalists all incorporate references to an earlier or sacred thread. For me, this is a precious aspect of the accreted history of jewelry. Artists who make the jewelry we work with come from the most significant jewelry-making Native American peoples, the Hopi, Navajo, Zuni, and other Pueblo communities of the American Southwest. (“Native American jewelry” comprises a much larger group.)

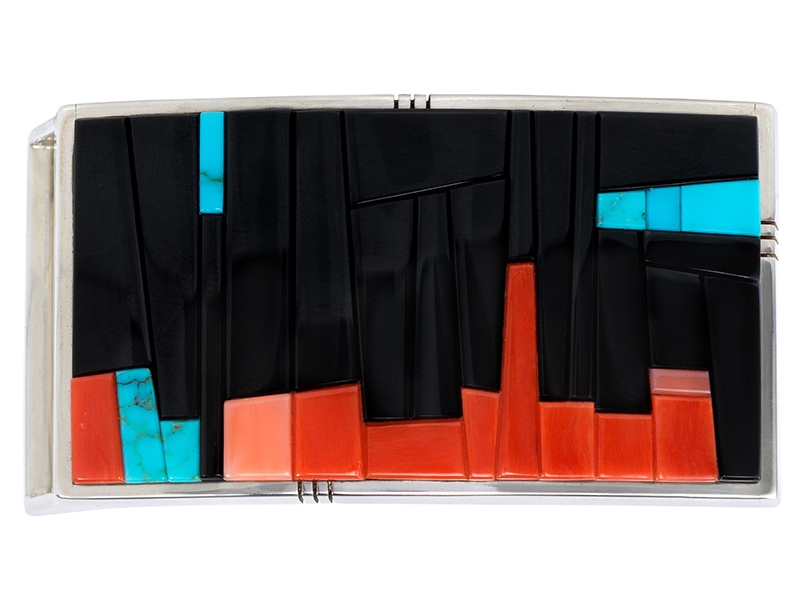

My personal, deeply felt connection is to the Southwest landscape. I have traveled often in the Four Corners area, including Arizona, Utah, and Nevada, and spent over 15 years in New Mexico annually. In these mythic landscapes, the red skies are inescapable, as is the stillness and spirituality of the earth, the vastness of geologic time. In these forbidding high mesas and buttes, this indomitable landscape, the Hopi, Navajo, and Pueblo peoples live and make jewelry. A belt buckle by Richard Chavez expresses this source of their inspiration.

My love of turquoise also drew me to Indigenous works. The Anasazi people who once lived here mined it to trade with Mexico, to make beads, and for mosaic inlay on shells. Turquoise is revered and appears almost omnipresent in Southwestern Native American jewelry today. American turquoise comes mainly from Nevada, Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, California, and Colorado mines. Only a small amount of high-quality natural American turquoise is coming to market now, as most mines are no longer operating. So be careful of the fakes, stabilized, dyed, or reconstituted stones which abound. Beautiful natural turquoise still exists in old jewelry, though, and remains available for new specialty pieces.

At Mahnaz Collection, we believe in the excellence of Indigenous artist jewelers. It seems ridiculous that the likes of Julian Lovato, Charles Loloma, Raymond Yazzie, Preston Monongye, Jesse Monongya, Richard Chavez, Lee Yazzie, Verma Nequatewa, McKee Platero, Edith Tsabetsaye, Pat Pruitt, and so many other former and current masters of the jewelry arts remain unacknowledged by mainstream buyers, auction houses, and even art jewelry collectors.

As an avid traveler, you often visit private jewelry collections or artist jewelers at their studios. What are those trips like?

Mahnaz Ispahani Bartos: My visit to Richard Chavez and Jared Chavez’s shared studio in San Felipe Pueblo, near Albuquerque, NM, was a memorable experience. Richard, the father, uses a mini architects’ drafting table, while the son uses a larger, fully equipped jewelers’ bench. I learned how Richard made each ring or necklace—the perfectionism, the hands-on, start-to-finish involvement with each artwork. He showed me an exceptional chunk of hardstone he had recently selected and the minimal tools he used to turn it into a jewel of Bauhaus beauty. Being with Richard in his shared studio with Jared gave me a far deeper understanding of the relationship between his spare, disciplined design, lapidary, and overall making processes and the clean, Bauhaus-influenced Laguna Pueblo jewelry designs that emerge.

One other memorable experience comes to mind: I spent a few days at the elegant library of Goldsmiths Hall in London researching our planned London Originals catalog and exhibition. I could visit the Silver Vault, with its extraordinary treasures—about 8,000 examples of renowned British silver from 1350 onward, some of it made by the leading silversmith-jewelers of the 60s and 70s, whose work I recognized. It was awe-inspiring, magical. In the room leading in and out, much-needed silver polishing was going on.

What is a day in your life like as a gallerist? Describe your daily routine.

Mahnaz Ispahani Bartos: No day is the same. Every day is busy. The team sits down together for a meeting. The doorbell rings. FedEx requires a signature. Simultaneously, the phone rings. Our policy is that a client needs to give us a quick call to make an appointment to visit the gallery. The doorbell rings. A longtime client shows up without a call. Bell rings again. A client with a scheduled appointment comes in. Diplomacy ensues. My team is very professional. They handle everything smoothly. I had hoped to have a quiet afternoon planning our two upcoming exhibitions scheduled in the winter season and researching some jewelry I might want to buy for one of the collections we build in-house. Anyway, all my plans for the day have come to naught. I leave my office to go in to join one of the clients. It is past 5 p.m. when we start our real day: the team meeting begins at last.

What do you think about contemporary art jewelry made during the past two decades? Do you have any favorite jewelry artists?

Mahnaz Ispahani Bartos: For those in AJF’s world, perhaps the relevant jewelry Mahnaz Collection sells is by Friedrich Becker, Klaus Ullrich, Ettore Sottsass, Pol Bury, Giampaolo Babetto, Torun, and Tapio Wirkkala, among others. We have a very fine Nordic early modernist collection. Since the mid-80s, I have personally collected the Forever rings of Bettina Dittelman and Michael Janks from Ellen Reiben, at Jewelers’Werk Galerie, in Washington, D.C. They are pure, brutalist, sensual, color-rich, and endless. I wear them all the time.

I know there is stress in the contemporary art jewelry world today as galleries shrink and artists find it harder to show work. A small number of makers show at multiple galleries at once. Yet several artists’ exciting heritage and current work make me optimistic. Collectors have given significant bodies of work to museums, and more are promised. The collector Susan Lewin introduced me to Annamaria Zanella’s work. Zanella was a thrilling, subtle, transformative artist. I like to explore her work along with that by Babetto, Ramon Puig Cuyàs, the late Kadri Mälk, Jacqueline Ryan, Giovanni Corvaja, Liv Blåvarp, Daniel Kruger, Helen Britton.

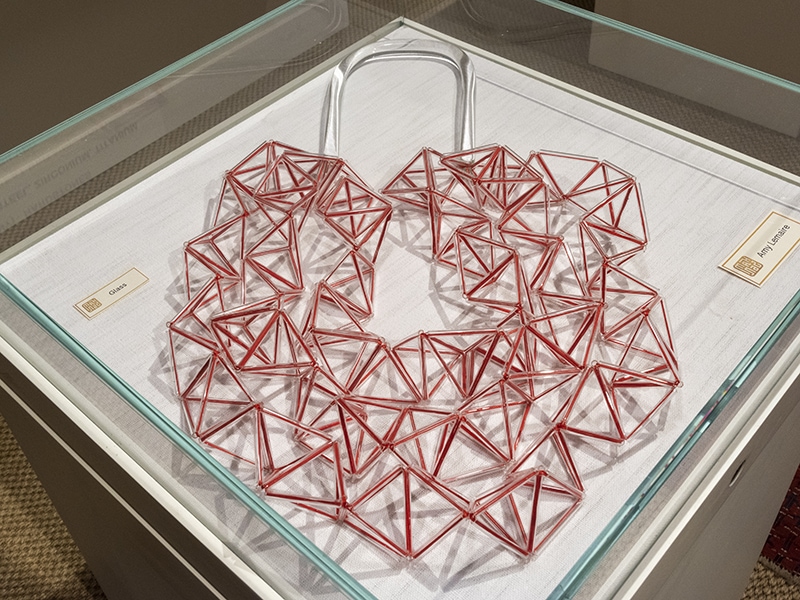

How can one not feel confident in the future given the jewelry of Veronika Fabian, John Moore, Kim Nogueira, Pat Pruitt, Kaori Juzu, Peter Hoogeboom, Lola Brooks, Vera Siemund, Sam Tho Duong, Terhi Tolvanen, Craig McIntosh, and so many others. I would add Julia Obermaier, Christopher Thompson Royds, and Amy Lemaire, who (along with Pruitt) we recently showed as a group.

I’m not always sure where the boundaries of art jewelry lie. Some jewelers, like Ted Noten, are successfully conceptual, while Helfried Kodré rejects that notion. I admire the artistry of both. Conceptual jewelry, when done poorly or over-intellectualized, seems to me the least successful jewelry.

I am impressed by the technical proficiency and radically imaginative use of new and older materials by many contemporary art jewelers, often used to avoid unsustainable, harmful practices. Furthering sustainability is an absolute today. In such areas, these contemporary art jewelers lead the way admirably and need to share lessons more widely.

Jewelry allows you to communicate an identity. Contemporary art jewelry’s experimentalism benefits from this, and its experimentalism benefits the broader jewelry world. Yet, in some instances, simply abandoning gold or other “precious” materials to take up cloth, paper, or tin, or embellishing metal with literal political messages, may not be the historically durable path. Let me give myself away as I did with my child: We need a strong dose of beauty and joy in this harsh world. Can contemporary art jewelry survive if defined solely as a protest movement against the “precious,” or can it evolve into another transformative yet enduring form of jewelry—part of our ancient history of adorning the body?

The field could welcome more diversity. Despite having an active East Asian component, it is Eurocentric, with some influential American makers. It might need to encourage new entrants, let some air in, link arms with broader communities of artist-makers of color, tribe, and creed, and open itself up.

Finally, what does contemporary art jewelry heaven look like to me? I can think of two possibilities: contemporary art jewelry has restored the brooch to its rightful place in the pantheon of jewelry. For this I am ever grateful. From Barbara Paganin to Ramon Puig Cuyàs to Kaori Juzu come works to die for… The second possibility: quite often, a stunning, spiraling, huge, fake, diamond, rude, tiny, gold, inscribed, ruby, up-in-the-air, glass, brutalist, jolie-laide Karl Fritsch ring comes along, standing out amidst his voluptuous output—I’m sure my other contemporary art jewelry heaven must be full of thousands of joyful Fritsch rings like that!

© 2023 Art Jewelry Forum. All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. For reprint permission, contact info (at) artjewelryforum (dot) org