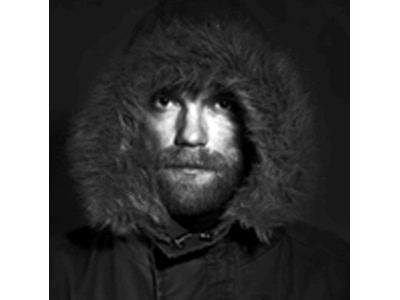

How do you measure a person’s size? Maybe in the echo that stays behind when an actor has left the stage? Kadri’s echo is loud, as is only possible with an extremely talented, passionate, and hard-working performer.

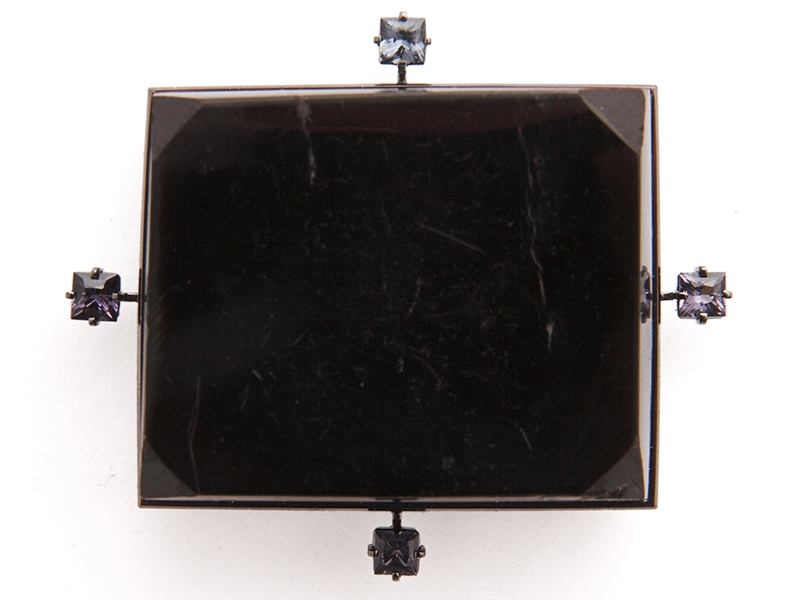

As a dedicated and fearless creative nature, Kadri had a talent that pulsated until her last breaths, unstoppable and playful. Each emotionally charged piece of jewelry she made reflects a personal experience shaped into the language of symbols.

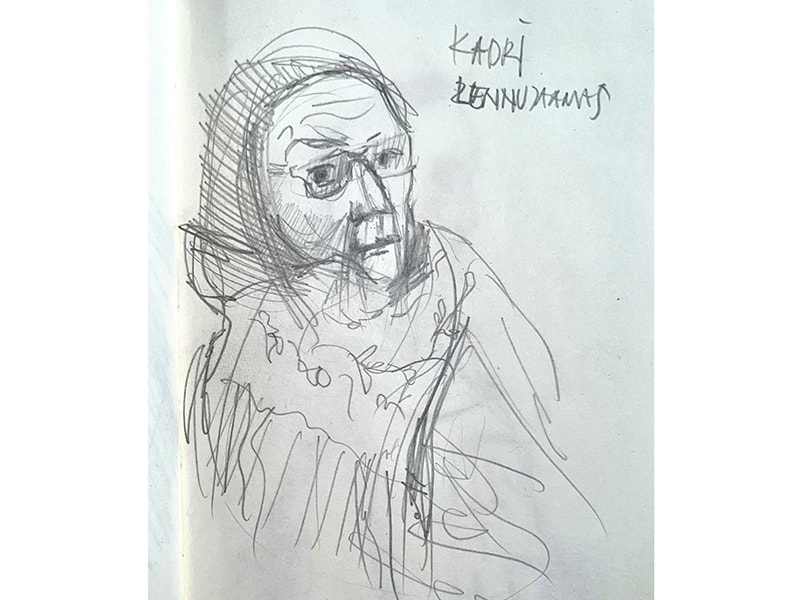

Kadri’s last exhibition, at the HOP gallery, was unexpectedly non-celebratory, an honest window into her home, her everyday life. The air in the gallery was thick with the smell of medicines, the walls and tables covered with her memorabilia. A guestbook from her parents’ home, leaflets advertising heart medicines, receipts, candles. Kadri was shamelessly sentimental. Sentiment as a personal flicker of experience, a feeling felt.

Kadri’s every move—the result of which could be a piece of jewelry, a bit of writing, a conversation—bore the strong stamp of her personality. For Kadri, everything was one. I remember the disdain in her voice when someone talked about style or beauty in Kadri’s work. Her darkness was not a style. Her whole being was permeated with a fatal sadness, the visible traces of which were jewelry.

“For me,” she said, “beauty was (and still is) mainly in thinking and feeling. I saw beauty in the way my mother baked a cake. Or how she embroidered, how much love she put into it. Or how my father sorted his portfolio so that he had all the materials/books for the lecture. Or how the turtle ate a cabbage leaf. In everyday life, in short.”[1]

A meeting with Kadri always left a mark. One was never the same afterward. Kadri, as a person with a deeply ritual-laden sense of life, selected the most talented people and consecrated them as part of her universe. She considered the education of ethics important. “Shared values are an important component of the work,” she said. “You don’t always have to agree. A weaker goal, an attempt to get rid of attitude/centeredness in order to reach the structures of big problems through the form of a work of art—from there, only through there, is the way.”

At her core was a human—mysterious, inexplicable, and dark. Kindness can be understood in many ways, but for Kadri it meant the Estonian painter Eerik Haamer’s saying that you can be an artist, but you have to be a human. Kadri’s specialty was gifts, ritual gratitude. These might manifest as a book adorned with a dark red velvet ribbon, a jar of onion jam, or the paper-thin mushroom pie she used to bake on Three Kings Day. But her care for others could take extreme shades. There were moments when it would seem demanding, autocratic.

As an intellectual creator, Kadri admired the feral. The themes of Mowgli reflected her desire for sincerity. Honesty matters. During the entrance exams to the Estonian Academy of Arts, she tried to find wild talents, uncut diamonds. Kadri was not fooled by someone’s agility and polished beauty. Country boys who smelled of the forest got bonus points. “My first encounters with beauty came from the countryside,” said Kadri. “Wild slopes, strawberry fields, Abja Manor and [its] park, dark ponds, arched bridges swinging over them, wolf canes … all this wild charm is hypnotizing. And silence. I was an only child and could only play by myself.” Due to her extraordinarily large presence and intellectual capacity, Kadri was no stranger to loneliness in later life. Aware of her value and strength, she kept her focus on the thin air of the high mountains. You are alone at the top.

Kadri mastered the word. I just checked. I have over 2,500 emails from her in my inbox. Opening them randomly now, I came across some wonderful puns. A personal and sharp way of writing, symbolism like in her jewelry creations. And irony! For all her gloominess, Kadri appreciated humor very much. Her letters were full of long, ironic vignettes in which she ridiculed stupidity, bureaucracy, political correctness, and modern technology.

She liked the contradictions of punk, the confirmation of artistic freedom where the difference between a king and a fool depended only on the point of view. “When the big and colorful traveling circus tent [was erected] next to the department store,” she wrote, “my father brought me from the country to the city to see this miracle. It was powerful! Bears rode on wheels and waved and whatnot. And those clowns! I firmly decided that when I grew up, I would become a clown myself.”

The source of Kadri’s magic was the desire to make the invisible visible. “There are things in life that no mere mortal can understand,” she said. As a creator, she knew the paradox of her task, but this constant stranding triggered her, the hope that, if the blind man consistently describes the elephant from different angles, the animal can finally be put together.

Such organic fragmentation characterizes the entire journey of Kadri’s work. She did one thing all her life, the next act growing out of the previous one. No series with beginnings and ends, no conceptually constructed bodies of work. Kadri was a mist scientist, the tamer of elusiveness. “And fog! My forever friend. Where did it come from, where did it go? How was it able to wrap everything around it? I still look at it with incomprehension and awe.”

I have always admired Kadri’s fearlessness. How was it that she was fresher and punkier in her creations and statements than her creative children? Kadri constantly surprised with crazy ideas, unconventional moves. She liked rebellion and adversarial people with noble principles. She shaped her life and work with a convincing stubbornness.

The all-encompassing nature of her selfhood terrified others at times. “I … [have] a hypertrophied sense of duty, which was probably inherited or cultivated. You have to!” If Kadri wanted something, she worked hard to get it. When it came to disagreements with others, she would find precise notes from 10 years ago in her archive, lobby behind the scenes to defend her position, and use all her skills and experience, so that when it came to battling her her opponents could only grasp at air at such strategic thoroughness. Kadri implemented her teacher Leili Kuldkepp’s teaching that profound preparation is the guarantee of victory.

A good upbringing and aristocratic ideals were central for Kadri. Democratic input from others was a daily inevitability, and despite it she navigated with all her might to establish her ideals and values. It might have seemed incomprehensible to the administrators in the academic machine who were shaping art education into a factory. Kadri hated administrative rules and did everything to ridicule them. She gave intellectually limited officials no mercy. Having sacrificed her life for the jewelry and blacksmithing department at the Estonian Academy of Arts, she observed the bureaucratization of education with special horror. She had come up in a time when a charismatic and tipsy professor could take a nap during his/her lecture. It was education as the school of humanity in all its complex variety. The gifted were forgiven much more easily then.

Kadri was a force, a visionary who brought her airy visions to life with wisdom, work, and dedication. Beware if someone tried to stop her or expressed doubts whether something was possible. Kadri’s flights of fancy had no limits. She thought big, her projects on a huge scale, unbothered by technical details or banal minutiae.

Kadri was a night owl. Among other things, she judged her friends based on who answered her 4 a.m. phone calls. Friendship was incredibly important to Kadri. She kept her friends, ready to throw herself into the fire for a loved one. “It’s all good when it’s new, but a friend—that takes time.” As a people person, Kadri could not keep apart from her friends. Even in the last months of her life, with the help of doctors, we tried to convince Kadri to give up her European tour. But in my heart, I understood Kadri’s desire to hug her soul mates one last time. So as the end neared, she took trips to Lisbon, Amsterdam, Munich, Padua, Tartu, all while confined to a wheelchair. Kadri could romanticize solitude and seclusion, but she could not live without people. There was always an invisible thread of human relationships around Kadri—friends, loved ones, students, soul mates. She had a small gift for everyone, a supportive card, three lucky stones.

When I went to study in Amsterdam, in 1997, Kadri gave me three unpolished diamonds so that I would stay free from the temptations of the big city. Kadri considered staying true to herself most important, and she couldn’t stand people-pleasing losers. That winter, she came to visit me in Amsterdam to make sure I was okay. At the academy’s Christmas party, she had a good time blessing everyone present—she dipped a red rose into a goblet of water and then spread it on everyone’s forehead as an invocation. Europeans aren’t used to ritualistic practices, irrationality, and sorcery. It created confusion. But it was as just such a shaman that Kadri established herself. A crazy woman of darkness from somewhere in the northeast.

Note: Kadri Mälk founded the charitable foundation Noor Ehe/Young Estonian Jewellery in 2008 to support the work of new, outstanding young jewelers in Estonia. Every bit of donations made to it go toward scholarships for young artists. To contribute, visit the foundation’s website or email Tanel Veenre, who is currently managing it. The foundation is grateful for every donation.

[1] The quotes in this remembrance are from Kadri’s letters, her book The Teacher, and an interview we started in November 2021. Unfortunately, the interview remains unfinished.