- Amelia Toelke works in many media: jewelry, illustration, sculpture, graphic design, etc.

- As an undergrad at SUNY New Paltz, she was drawn to the way metal encompasses utilitarian objects like buckets and spoons, but also ceremonial objects like reliquaries, censers, and jewelry

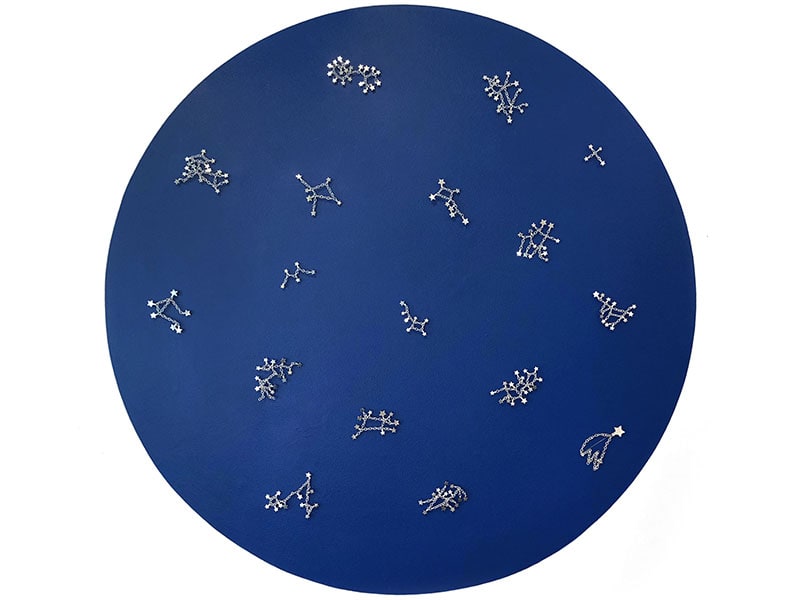

- She designed the logo to celebrate AJF’s 25th anniversary, which we’ve used throughout 2022

Amelia Toelke is a multidisciplinary artist who is fluent in the language of adornment, whether that be in jewelry, painting, or sculpture. Her Gem Face series translates 3D jewelry into humorous 2D paintings, highlighting the emotions and nostalgia imbued in jewelry. Toelke’s practice has taken her abroad to cities such as Lanzhou, China, and Tbilisi, Georgia, to participate in artist residencies. Her work has been published in Metalsmith magazine, The Washington Post, and 500 Enameled Objects.

Amelia Toelke is a multidisciplinary artist who is fluent in the language of adornment, whether that be in jewelry, painting, or sculpture. Her Gem Face series translates 3D jewelry into humorous 2D paintings, highlighting the emotions and nostalgia imbued in jewelry. Toelke’s practice has taken her abroad to cities such as Lanzhou, China, and Tbilisi, Georgia, to participate in artist residencies. Her work has been published in Metalsmith magazine, The Washington Post, and 500 Enameled Objects.

Olivia Shih: When I visited your website, I laughed when I saw the artist portrait you chose—it’s a brilliant illustration your dad did of you as a child and involves a beloved vest, cereal, and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. What was it like growing up in a creative household?

Amelia Toelke: It was wonderful! There were always materials around that my sister and I could use to create our own projects and worlds—cardboard, lots of different kinds of paper, rubylith (a masking film), markers, Letraset sheets, and a photocopy machine. I was probably using an X-acto knife as early as I started using colored pencils. My sister and I were always making things and often we were making things together. Our parents worked at home, and I think that prompted us to keep ourselves occupied. Subconsciously, and for better or worse, there was the idea that home was a place to work.

Also, because our parents were around, we couldn’t get away with just watching television. But it kept us creative (and don’t worry, we definitely watched our fair share of TV). When we both went to art school, our parents were fully on board, almost expecting it! Because our parents were self-employed, it always felt possible to live a creative life—that work and creativity could be connected and that one’s own skills and ambition could be a means of making a living.

Jewelry charms play a prominent role in your work—what is it about charms that is so compelling to you?

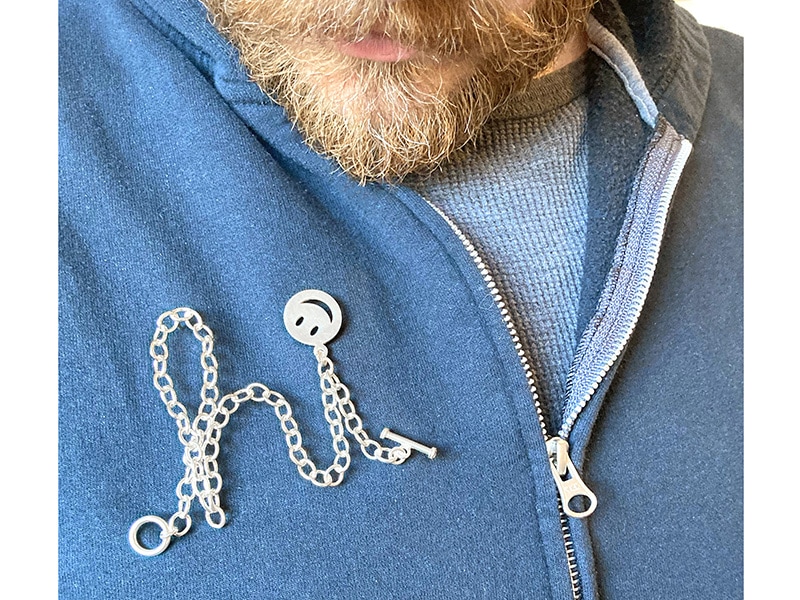

Amelia Toelke: Charms are visual language on top of visual language. They are not only symbols that stand in for complex stories. By being jewelry, they are embedded within personal space, the body, and public and private interaction. I am interested in the way that these layered meanings outline complex narrative. Just like how a word can have multiple meanings depending on context or culture, a charm will evoke different definitions or memories depending on the person wearing the charm or looking at the charm. In that way, their meanings are both collective and individual. They have the power to contain entire stories and experiences. A charm might stand in for a trip abroad, or 25 years of marriage, or a life-long passion for photography.

In my work, I include charms in our vernacular language of symbols. I am also attracted to the notion of cliché and the parameters that determine it. When I use vintage charms in my jewelry, they bring unknown histories and stories with the shapes of the charms as little clues. When I flatten the charms into graphic icons, they are like hieroglyphics or rebus puzzles.

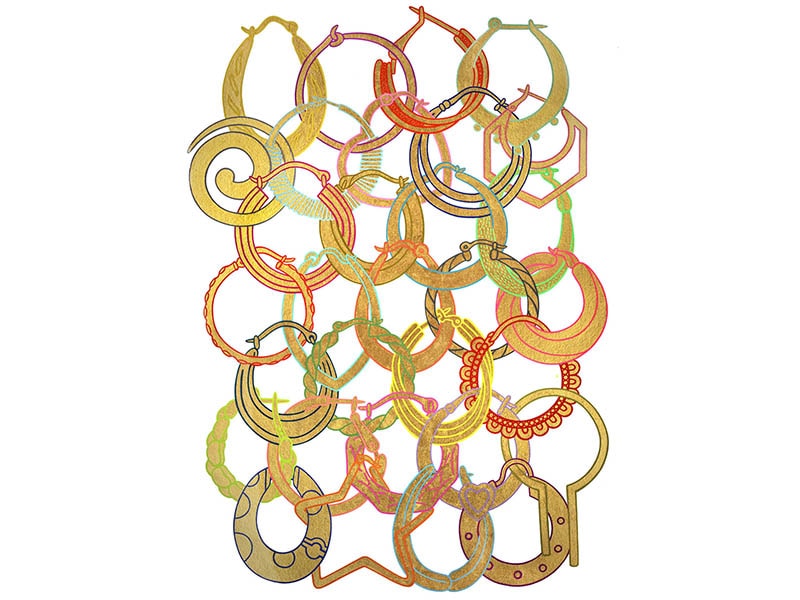

In your Gem Face drawings, you compose expressive faces with jewelry. What inspired you to create this series?

Amelia Toelke: I don’t remember the exact moment. I do remember that at some point I saw a necklace laid out with earrings and thought, “Face!” At the time, I was doing collages with emoji images, so faces were on my mind. When I made the first one, I remember feeling a little self-conscious that it was too silly. But it was such a joy to make and it made me so happy that I figured I should lean into that feeling. There is nothing like laughing while at the studio. Jewelry is also so intertwined with our sense of self. By literally creating expressive faces with jewelry I could put this idea front and center.

How did you choose which pieces of jewelry to depict in this series?

Amelia Toelke: Partly I chose pieces that I felt like would translate well to the page. I am not a trained jewelry renderer or even a painter, so I looked for pieces of jewelry that I felt would work with my more graphic/flattened style of illustration. I thought about color, and sometimes I had an idea of what kind of piece would evoke a specific feeling.

I also intentionally made unexpected pairings. I could have easily used matching sets of jewelry, but I thought it was more interesting visually to create these juxtapositions. It spoke to the true depths of one’s jewelry box and, as such, one’s personality. Most people have jewelry that they wear and jewelry that stays stored away for various reasons. All those pieces describe different aspects of a person and their history. So many of us keep the jewelry from our childhood even though we don’t wear it. Or we might have a really beautiful heirloom treasure that gets worn maybe once every few years. It made sense to create this series using a mix of fine, contemporary, historical, and vintage jewelry.

Speaking of your 2D work, you often blend 24-karat gold leaf into your drawings. Applying gold leaf to paper can be a meticulous, time-consuming chore. Why are you drawn to this technique specifically?

Amelia Toelke: Part of what I like about gold leaf is that it is meticulous and time-consuming! As someone steeped in the world of object making, I am drawn to the historical and tactile qualities of gold leaf. To me, the materiality of gold leaf also brings it into the world of objects. The space between object and image has captured my curiosity for a long time. This is a theme that shows up throughout all of my work, whether it be on the page, on the body, or on the floor. By using gold leaf, I feel like I can create a hybrid object—one that straddles the realms of 2D and 3D.

Gold is also just so magical. It doesn’t tarnish and it is luminescent. While it makes my work impossible to photograph, it really is amazing to see how a piece will suddenly glow. Every time I gold leaf something, I am reminded why we humans love this metal.

Tell us about your training and how you became a visual artist who moves between jewelry, drawing, and sculpture.

Amelia Toelke: My high school art program was pretty bare bones, but I have always loved drawing and making small things. As a kid, I spent a lot of time making beaded jewelry. I also made many tiny objects using polymer clay and paint. I remember making a tiny tube of Crest toothpaste with a toothbrush and a plate with a wee hamburger, a milkshake and french fries. A lot of these objects became pins, but some were just objects.

After graduating, I went to SUNY New Paltz. When I took my first metals class as a sophomore—with the incomparable Myra Mimlitsch-Gray—I fell in love. There was something so exciting about focusing on process and technique. It felt really natural. It was refreshing. At this time, I was not only being exposed to a whole new field of art and art making, but I was also seeing more art in general—art that was witty, subversive, funny, and smart. I was drawn to the way metal encompasses utilitarian objects like buckets and spoons, but also ceremonial objects like reliquaries and censers, and, of course, jewelry.

Having this range of material to work with was inspiring and allowed me to understand how process can be connected to content. It also spoke deeply to what I knew—my parents’ house is an unassuming trove of treasures. It has been richly painted with faux finishes, colorful patterns, and a trompe l’oeil window. It is filled with an eclectic mix of salvaged stained glass, repurposed architectural fragments, and collections of objects old, new, and handmade.

Next, the three-year interdisciplinary MFA program at UW-Madison was such a gift. It gave me permission to explore making more non-functional work (a.k.a. sculpture). I learned so much from working with Lisa Gralnick and Kim Cridle. When the metal grads were assigned a 100-drawing project, I thought about approaching the project modularly as collage. I drew components separately and then put them together, which was more comfortable and was akin to the process of working three-dimensionally. I was hooked. And the best thing: drawing is not bound by the rules of the natural world, and I could create improbable vignettes that didn’t have to contend with gravity. Bringing drawing back into my life in a way that complemented the rest of my work was defining. Since then it has become integral to my practice.

You also create public art, which is exponentially larger than most jewelry and comes with its own set of rules and challenges. What is your conceptual and technical process when creating public art?

Amelia Toelke: In many ways, I consider jewelry to be public art. Both are out in the world, on display, meant to be seen and experienced. Both require the body to play an active role. We might think that jewelry is “quieter” because it is small, but context determines everything. A large necklace might not actually be very large when compared to public art but, when worn, its scale in comparison to the body has a big effect.

The 2020 piece Underpin & Overcoat was a collaboration with my dear friend Andrea Miller. It was a multi-site public work where buildings “wore” large pinback buttons, and I was thinking about the messages we put out into the world through what we place on our bodies. It wasn’t about just making a giant pin, it was also about how these giant pins were so easily and readily at home in a new context.

How do you make a living as a visual artist? Are you a full-time artist, or do you take on other jobs that sustain your practice?

Amelia Toelke: I have always juggled multiple jobs/things at a time to make a living. Currently, I do graphic design and publication layout as a primary means of supporting my practice. I have worked at galleries and done odd jobs. I also take on custom projects/commissions and sometimes teach part-time. I have sort of figured out a way to make it work.

What do you cherish most in the contemporary jewelry field? What is one thing you would change?

Amelia Toelke: I feel incredibly lucky to be part of a field that is also a community. If you don’t know someone, you definitely know someone who knows that other someone, so it always feels like you are in good company. I wouldn’t change anything about the community. I just wish that more folks would see how vibrant contemporary jewelry is!

Lastly, what thought-provoking content have you consumed recently?

Amelia Toelke: I love fiction, so I really enjoy reading novels even if I don’t do it enough. I find that the act of immersion in a story is really fruitful for my practice. I read Avenue of Mysteries, by John Irving, earlier this year. He is one of my favorite authors, and it was the perfect blend of reality, magical realism, absurdity, family, humor, past, and present. Earlier this fall, my husband and I took a trip to Montreal and went to the Contemporary Art Museum. We were blown away by the exhibition on view—Mika Rottenberg. I am late to the game with this multidisciplinary artist who makes surreal videos and sculptures. The videos on view were mesmerizing, lush, with cyclical narrative that blended fact and fiction. Also, very jewelry-adjacent.

Thanks for your time, Amelia, and thanks for creating AJF’s 25th anniversary logo!