Rosemarie Jäger had been noticing how many couples there are in the jewelry world, and suddenly one day, she realized that it was a great idea for a series of shows. This one, with Beate Klockmann and Philip Sajet, is the first, and appropriately it is called Frühling or “Spring” and is the beginning of the series. It is fascinating that there are so many couples working together or at least living together. It will be fun to interview some of them and understand better how that works. I am very curious.

Rosemarie Jäger had been noticing how many couples there are in the jewelry world, and suddenly one day, she realized that it was a great idea for a series of shows. This one, with Beate Klockmann and Philip Sajet, is the first, and appropriately it is called Frühling or “Spring” and is the beginning of the series. It is fascinating that there are so many couples working together or at least living together. It will be fun to interview some of them and understand better how that works. I am very curious.Susan Cummins: Please tell the story of where you were born and raised and how you became interested in making jewelry.

Beate Klockmann: I was born in the GDR (German Democratic Republic) and raised up in a little town in Thuringia in Ilmenau. Johann Sebastian Bach lived in this area, and I like that because I feel connected to his music, but I have no musical talent at all. My father and my mother both worked in the porcelain industry, and I got my drawing talent from my grandmother. She was a workaholic, making cloth the whole day long with a lot of creative ambitions, but she did not have a lot of possibilities during the war. I decided to make jewelry spontaneously after seeing a slideshow that was shown to introduce different departments of the Burg Gibichenstein, Hochschule für Kunst and Design, Halle, Germany. I remember I was touched by a photo of a classically made little precious box with blue enamel and golden animal inlays. I hadn’t looked at jewelry before.

Philip Sajet: I was born in Amsterdam and raised by a French mother of Russian descent and a Polish-American (step) father. We travelled to Djakarta, Indonesia, where I saw a lot of Chinese antiques—so beautiful, so magnificent. I love tradition. I think that 96-percent of what I do is based on accumulated knowledge. Well actually, I am being very presumptuous here. I should have written 98.7 percent.

I was very fascinated by these small objects with colors and colored stones and enamels. Their (heavy) weight felt so powerful. I think I fell love with these objects several times—When I saw the jewels in the palace of the shah when I was 13 (1966), and then when I saw Egyptian jewelry. But the time that made me decide to also do it was when I saw the jewelry of Giampaolo Babetto and Francesco Pavan. That was in 1977 in Gallery Nouvelles Images. I remember the first question I asked my teacher Karel (Niehorster): “How do they get that intense yellow color?” “Well, by using gold” he answered. But it was so expensive—8 Dutch guilders a gram (2.5 US dollars)!

How did you meet?

Beate Klockmann: In 2001, I was a student in Halle Burg Gibichenstein and busy with my last pieces for my final exam. Philip was supposed to teach, but because of certain circumstances, his students had to finish another project and didn’t appear the first days of the workshop. So Philip focused on the only person available, and that was me. He was sitting next to me and was solving problems for me that I didn’t have days before. And I liked to solve these new problems with him.

Philip Sajet: Now, here the accounts may differ. I was in Halle in 2001 in March. I was doing a workshop in Burg Gibiegenstein. The class I was guiding was the year before last. There was a girl (young woman, of course) who was preparing her final year’s work. She threw the red-hot metal in the pickle. That made a sizzling sound. I explained that the silver or gold doesn’t like getting a shock like that, and coincidentally, neither did I. My request to refrain was met with a somewhat diminished fire/fluid encounter. It wasn’t red hot anymore but still warm enough to make a sound. Funny enough, a week ago Beate did the same thing again, 12 years later. I discovered that Beate’s horoscope was a fire in water and a water-in-fire dominated constellation. I don’t know what that means, but I thought that it was remarkable. Beate also made a piece called Fire on the water, and I made a ring for her with rubies and aquamarines.

In the beginning, I had the impression that wherever I was standing Beate stood in front of me. I made an appointment with Rudolf (Kocea) in a bar, and all over sudden, Beate was sitting between us. I actually suspected that Beate threw that hot metal in the pickle to attract my attention. But she has never given me a definite confirmation of this suspicion.

I know that her account of our meeting was that wherever she was sitting, I happened to stand behind or next to her. So, what this proves is that history should always be taken with a certain measure of suspicion.

Beate Klockmann: Since 2012, we have lived in a little village next to Hanau in Frankfurt. We are both strangers here. We work in the same studio. Our studio is always changing. There is a continuing discussion about how it should be organized.

Philip Sajet: In Bruchköbel, near Hanau, where Beate teaches in the Hanau Zeichen Akademie. But, a few months a year I live in a house we own in Latour de France, a winemakers village where we lived for many months in the past. Funnily enough, the wine of that region can actually be bought cheaper in supermarkets near Munich. We have made the living room of our house in Germany into a studio.

Do you use the same equipment?

Beate Klockmann: In general, we use the same equipment. There are only a couple of instruments that are personal.

Philip Sajet: We share the big tools, and we use our own smaller pliers and files.

Beate Klockmann: Our days are not really divided into studio time and relaxing time. The studio is the center of our house. So, everybody is doing things there, such as listening to music or reading books. We discuss things there as we paint, often with our daughter. Philip also has apprentices, and he makes music there, too. The studio is also the place where the birds are living. So, there is a lot of interaction. If all goes well, it creates a good atmosphere for making jewelry along with other things.

Philip Sajet: Our hours differ. I am a daytime worker, and Beate likes the nights. In a way, we work shifts. We do interact, of course, but usually it is small talk. We do ask each other for advice, but more often than not, it is not followed. But, a major thing we give each other is courage. When one of us wants to make a piece, we spend a lot of materials and time in making it very particular, which turns out to be very expensive as well. So, there is an inclination not to do it, but we say to each other, “you really must make that piece.” That is very nice.

Give us a description of how your workday goes.

Beate Klockmann: Because I am a teacher at the Zeichen Akademie in Hanau, I have only one to two days a week to work in the studio on my own work. I like to work together with Philip, and sometimes with an apprentice, but the daytime can be very chaotic because of our daughter Jura. That’s why I like to work during the nighttime so much. I have the illusion that I have endless time to work, and I can be alone with my work for a while.

Philip Sajet: I have the luxury of getting a late start. I wake up at 8:30am, have coffee in bed, then shower and do administrative chores. At around 12:00, I might finally start working. Then, two hours later, I make lunch. Right now, the daily meal is brown rice in the Japanese rice cooker, peeled aubergine, tomatoes, sesame paste, seaweed, eggs, sesame seeds, sunflower seeds, pepper, thyme, garlic in the peel (en chemise, as it is called in French), and at the end, I add oil olive and sea salt. It’s so easy. Just throw these ingredients in, close the lid, and half-an-hour later, it’s done. I try to get a full six hours of work. My best hours are my last one-and-one-half. If I get that a minimum of five days a week, I can reach my aim of an average of one piece a week.

What questions do you ask yourself when preparing to make a piece?

Beate Klockmann: I look at my messy table and ask, or better, I try to feel which piece motivates me to work on it, and then I simply start to work on it. In general, I am just happy if I am working, so I try not to think about it too much before I start.

Philip Sajet: Is it technically feasible? Is it pretty or ugly? (Not that one or the other might decide an outcome.) How high are the investment costs? Will it fall well on the body? Does it have a meaning? Is there a necessity?

You both seem interested in unusual materials and stones. How do you decide, for example, to use the sole of a shoe in a necklace?

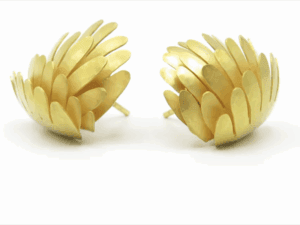

Beate Klockmann: Once in a while, I like to take bigger risks in my experiments, also in choosing materials—such as glass, textile, enamel, paper—but after a while, I always go back to working with gold.

Philip Sajet: In my case, in my mind’s eye, I put everything I see in a circle. So, the inside curves of the soles placed that way make an almost perfect, big new circle. Then, the next thought is, “Oh this is really too awkward, and nobody will ever wear that!” There is also a reference to the Paul Simon song (I recently discovered that we have the same initials) Diamonds on the Soles of Her Shoes. Well, diamonds would have been a lot of investment, so I went with rubies, and it was a more affordable one. Also, the color went well, the red with brown.

Do you think you influence each other, and if so, how?

Beate Klockmann: Sure, we influence each other. The good thing is that I always have a highly critical public in the house. So, I feel well trained in handling the different reactions when I exhibit my work. On the other hand, Philip gives me special compliments if I have a bad day. In general, we both try to support the other in whatever strange thing we are doing. If we didn’t, then everything would become boring.

Philip Sajet: Yes, definitely. We maintain a high level of quality, and we judge how major a piece is and whether it is boring or not. We aren’t shy about saying what we think to one another.

What have you seen, read, or heard lately that has excited you?

Beate Klockmann: I read a little book called Montauk by Max Frisch. I liked it because it was full of wisdom and very nicely written. But really, to be honest, the highlights I get at the moment are the intelligent expressions of our daughter. At six-years-old, her drawings, conversations, and so many essential things are on the table, and with such a surprising clearness, that I enjoy it a lot.

Philip Sajet: Lion Feuchtwanger’s The Oppermann’s is deeply disturbing and dramatically describes the destruction of a family in an intolerant totalitarian regime. But there are so many magnificent books. American Psycho by Bret Easton Ellis is also a magnanimously written novel about a very ugly person.

The music I listen to a lot lately is from Nils Frahm, and always Bach, of course.

I know it’s very fashionable, but I love (almost) all the movies from the Coen brothers.

My absolute favorite is No Country for Old Men, and my absolute favorite scene is where Anton Chigurh (Xavier Bardem) confronts the gas station man by flipping “his” traveling quarter.

Thank you.