Patti Bleicher and Eileen David started Gallery Loupe in Montclair, New Jersey, United States, six years ago. They show a roster of both established and emerging international artists and are interested in furthering the dialogue that contemporary jewelry evokes. In February they asked Kiff Slemmons, an established American artist, to show her most recent work in an exhibition called Huesos. I caught up with Kiff and asked her a few questions about her work and her interests.

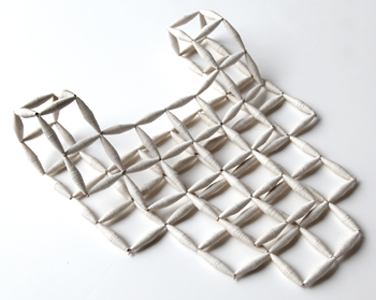

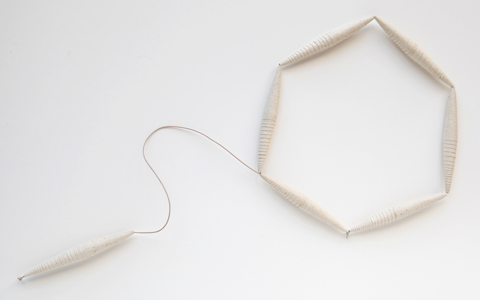

Kiff Slemmons: These pieces emerged from an art residence at Arte Papel Oaxaca. The artist and members of the atelier did the work together. Early pieces referenced African jewelry with discs built up into sculptural bead forms. Later pieces exhibit the techniques of folding, cutting and hollow-punching, rolled and formed paper pulp. The atelier is dedicated to ‘reviving the pre-Columbian tradition of making paper from natural fibers.’ The result of this project is a collection of paper jewelry, which is highly sculptural and utilizes indigenous plants, fibers, natural and synthetic dyes.

Talking about paper in Oaxaca involves countering assumptions about the material, its fragility versus strength, the metaphoric implications of paper in this regard, in relation to books and the culture at large. What paper meant in pre-contact culture in Mexico, its magnified significance after conquest and its current place in culture today. How I came to work as I did there means looking at my previous work, how it might have led to such a project which involves a kind of world view through jewelry and writing. My work is really not technique determined, even with the paper. It’s ideas that interest me first and the possibility of being poetic in a visual language.

Patti Bleicher and Eileen David started Gallery Loupe in Montclair, New Jersey, United States, six years ago. They show a roster of both established and emerging international artists and are interested in furthering the dialogue that contemporary jewelry evokes. In February they asked Kiff Slemmons, an established American artist, to show her most recent work in an exhibition called Huesos. I caught up with Kiff and asked her a few questions about her work and her interests.

Kiff Slemmons: These pieces emerged from an art residence at Arte Papel Oaxaca. The artist and members of the atelier did the work together. Early pieces referenced African jewelry with discs built up into sculptural bead forms. Later pieces exhibit the techniques of folding, cutting and hollow-punching, rolled and formed paper pulp. The atelier is dedicated to ‘reviving the pre-Columbian tradition of making paper from natural fibers.’ The result of this project is a collection of paper jewelry, which is highly sculptural and utilizes indigenous plants, fibers, natural and synthetic dyes.

Talking about paper in Oaxaca involves countering assumptions about the material, its fragility versus strength, the metaphoric implications of paper in this regard, in relation to books and the culture at large. What paper meant in pre-contact culture in Mexico, its magnified significance after conquest and its current place in culture today. How I came to work as I did there means looking at my previous work, how it might have led to such a project which involves a kind of world view through jewelry and writing. My work is really not technique determined, even with the paper. It’s ideas that interest me first and the possibility of being poetic in a visual language.

I wanted to see what we might have to say about paper, about simplicity and elaboration, about structure and design, about durability and the ephemeral, about the value of material and idea in jewelry, the possibilities of improvisation and collaboration, about the spirit of invention in usual and unusual circumstances with limited but focused resources. All of which would never have happened without the combined effort and skills of all of us.

I was thinking of how we could reaffirm the use of paper in jewelry and of jewelry in art.

You were in New York recently for the opening of your show at Gallery Loupe and to give a talk at the 92nd St Y. I know you take these talks very seriously and they are as much about being creative for you as is making a piece of jewelry. Can you tell us a bit about this one?

Yes, I always put together talks as a kind of scripted performance. Making a talk is very much like making a piece of jewelry. And I want to wear it well if I’m out. I’ve often thought I wanted to write and ended up making jewelry as if it were writing, both in a narrative and a poetic sense. I want to communicate something about jewelry, its importance in the culture and at the same time include it seamlessly into the purview of art. There is an element of the subversive in the way I talk about jewelry, partly by being both poetic and plain speaking in my approach. I like to build up access to more complicated ideas through these layers. Form and structure are powerful tools.

I began the talk by saying how after 35 years experience working as an artist, I now can be an anthropologist – a cultural and material anthropologist of my world of work. I go on to talk about seeing the collection of jewelry from Tomb Seven at Monte Alban near Oaxaca in 1966. I said: ‘This collection of jewelry was diverse and layered and highly symbolic. It was both representational and abstract. Made from all kinds of material in addition to the more expected gold and silver – shell, coral, amber, pearls, turquoise, jade, obsidian, bone. Evidence of a culture. Not on the scale of the pyramids but powerful in its COLLECTIVE presence and in its suggestion of something larger than the scale of an individual piece. Though I didn’t know the specific layers of meaning in these pieces, they left an impression, including the threads that I can now seeing running consistently through my work: the idea of scale, the power of the small; the language of materials, their possibility for metaphor; and the idea of array, exploring in fragments and variations, more than one to make one.’

I then talked about these threads in different bodies of work as well as the importance of exhibition as site for the work, almost more than the body as site for jewelry. For me it is not so necessary that jewelry be worn, though most of my work is quite wearable, but rather it is the implied site as jewelry that must remain. I like that they be shown as a collection of pieces. Their presence and what they are as art requires a collection of them. And though I cannot ‘afford’ to keep them together, the exhibition allows once again this particular presence.

While you were in New York, what did you see of interest?

I say in my talk that I’m trying to create a kind of geology of presence and certainly New York is that, with all its layers.

I know you were an English major in school and have a continuing interest in reading. So I am always interested in hearing about what are you reading?

In school I was aimed toward comparative literature – French and Russian. I ended up with a double major in French and Art. The art part was the last year of school when I took only art courses since I had enough credits already for a major in French.

When did you move from Seattle to Chicago?

We moved in 2002.

Do you think your move affected your thoughts about what you wanted to do with jewelry?

What is the thread of thought that runs through all your work? Can you talk about how it continues through from your earlier work in Seattle to this series of paper pieces?

Three threads that have run through my work over many years – scale, the language of material and the idea of more than one to make one – coalesced once again.

What are your ambitions?

I like to use the strength of the diminutive to counter assumptions about jewelry, to add to ideas about art and to contribute to the continuing worth of the physicality of ideas. Jewelry is not a usual site for art, though it often appears in museums as indicators and identifiers of past cultures. It is the unexpectedness of jewelry as art that has held my attention all these years.