The last of 17 filled-out questionnaires has just landed in my inbox, and once again, I marvel at the availability and professionalism of the organizers of jewelry events (which will be abbreviated as “JEs” in the rest of this article) around the world: All have answered my call, and responded, kindly and efficiently, for information requests regarding “their” event.[1] I also marvel at the variety of respondents. They range from organizations big enough to have outsourced press officers (TEFAF, Collect, Design Miami/) to your typical makers’ collective: large-ish groups of overtaxed, voluntary champions of their local scene, who typically are multitasking their way through exponential hours of unpaid work. They are no less professional: They simply do this between midnight and 3 a.m.

The organizers’ availability may have to do with the fact that I labeled this briefing as a “report for collectors”: “Collectors” means buying power, and this is a sort of power that has often been billed as ageing and fragile, if not frankly endangered. They are an attractive population to have around fairs, and if the surge in jewelry events is anything to go by, people are gambling that the very special ecosystem of international JEs will be too tempting for collectors to pass up.

The reality of the jewelry collectors’ pool is not, however, the subject of this briefing: The marketability of jewelry weeks is. There is a surge—I knew that before I started this research—and it is exciting. But it’s not clear if the surge in JEs actually equates with a solidification of an international primary market for contemporary jewelry. Upon reading in detail about the ambition and program of JEs around the world, only about half turn out to have a primary commercial drive, always spiced up with educational plug-ins. The rest of them started as educational/promotional endeavors, to which commercial projects were later added. As a result, the umbrella expression “jewelry events” I use in this report covers a large spectrum of events that all feature a mix of commercial and noncommercial exhibitions, lectures, and professional development and networking opportunities. The main issue here is readability: The world’s JEs have very different aims, and though the “Jewellery Week” brand seems to be catching on, it doesn’t quite mean the same thing in Munich as in Florence: The purpose of this article is to parse them out, and provide you with a hitchhiker’s guide to the global jewelry agenda.

Before we start, a word on extent: This article only took into consideration recurrent events that feature a substantial element of contemporary jewelry in their program. It does not include the Parisian Louvres des Antiquaires, for example, which showcases extraordinary specimen of historical and fine jewelry but almost no contemporary work, or Grey Area, a spectacular transnational project that took place in Mexico in 2011 and was conceived as a one-time extravaganza. It does include, however, five events that only happened once but are working on their second edition: the Parcours Bijoux,[2] in Paris, Stockholm’s and Athens’s Jewellery Weeks, Melbourne’s Radiant Pavilion, and Tokyo’s Play Jewellery. AJF has reported before on a number of these events: The name of each one in the introductory listing hyperlinks to all the articles we have published on each.

Categories

Out of the 22 jewelry events listed below, only four existed before 1980, and no less than 14 were established—or became jewelry-friendly[3]—after 2005. This is remarkable in several ways. Firstly, because the trend parallels that of the art market: According to The Art Newspaper, in 2015, collectors could choose from 269 art fairs around the world, up from 105 in 2005.[4] Similar statistics would suggest a similar market dynamic, and in particular that jewelry galleries are bowing to a general shift to fairs as the focus of collectors’ interest, and channeling their efforts toward temporary events with global appeal.[5] None of them have abandoned their brick and mortar yet, and in fact, they can’t: Commercial fairs require galleries to have substantial exhibition programs in order to apply and be selected.

The word on the street is that Frame, Design Miami/, SOFA and Collect can function as sales amplifiers, because they are good news for collectors: Heightened competition brings out exceptional work in a small, walkable perimeter. And this is good news for galleries, which can hope to make half a year’s turnover over four days. In theory, the support of well-established commercial machines that straddle multiple fields—such as Miami/, Collective and Spring Masters—could be a game-changer for the sustainability of the jewelry market, but the jury is still out on that one: It is too early to say whether hybrid events will encourage art or design collectors to “diversify” into jewelry, or draw jewelry collectors away from brick-and-mortar galleries and into commercial fairs. The first part on my listing will focus on these fairs, and look at how they compare.

The second part of the listing is devoted to celebratory and educational endeavors: a tight group of four seminal juried exhibitions and two meeting platforms—one of which functioned as talent showcase and transmission tool back in the days when contemporary jewelry was but a speck in the cultural horizon. All of them have now become “fairs” in their own right, but I will argue that their original mission still defines their identity.

The final section covers the new phenomenon of citywide jewelry weeks: the pull-yourself-by-the-bootstraps format of pure statement events that focus on exposure rather than sales. This model has a number of advantages: richer, more daring exhibition formats, more collegial organization, openness to self-driven projects and artist initiative, and a general open-door policy that literally makes these fairs accessible to almost anyone with enough cash to purchase a plane ticket, and the network to support themselves locally… The model also has some disadvantages: This flurry of endeavors does not so much create a market as confuse the issue of marketability, by relying on a large number of nonjuried, self-promotional initiatives. For sure, they are a great way to have direct access to artists and their work, but specialized collectors rely on advisory structures, whether soft or hard: They’ll flock to Frame, because it has a rock-solid legitimacy, but may not be so interested by the Athens Jewelry Week or the Parcours Bijoux, which do not have a well-established brand or support structure, or a sufficiently recognized jewelry scene. We will see what collectors are missing out on—if indeed they are.

1. COMMERCIAL FAIRS FOR GALLERIES

|

COLLECT, LONDON

|

FRAME, MUNICH |

SOFA, CHICAGO

|

|

COLLECTIVE DESIGN FAIR, NY |

DESIGN MIAMI/, BASEL |

TEFAF, NY |

|

DESIGN MIAMI/, MIAMI |

Explicit criteria of excellence, long and strenuous application processes, high exhibitor fees and entry tickets, but also “top-of-the-crop” capsules, lectures, and VIP events: Commercial fairs are in the business of making money from jewelry lovers either side of the counter, and they do so by ensuring that their brand has the right blend of exclusivity, excellence, and support of the arts. SOFA set the tone in 1994—and helped establish the idea of the spectacular craft fair, where exceptional work by living makers could be seen and purchased. Collect followed in 2004, first at the Victoria and Albert, and then at the Saatchi gallery. Its very tight application criteria—both artistic and commercial—give some idea of the dynamics at work:[6] The organizers’ job is to manage desirability in order to create a virtuous circle of value increase that affects the work presented, the exhibiting galleries, and the fair itself. (Collect has thus maintained a very high profile despite recurrent uncertainty about the longevity of its partnership with the Saatchi—and a one-year gap to “regroup and revamp” in 2016.[7])

Over the last decade, two new fairs have been created (Frame, in Munich, and Collective Design, in New York), Design Miami/ has opened its doors to contemporary jewelry galleries, and Spring Masters—where Didier, for example, exhibited last year—has been taken over by TEFAF, the behemoth behind the European Fine Art Fair (Maastricht).

What does this means for collectors? Theoretically, that you can be engaged by high-end artist or contemporary jewelry from early February (in London) to early December (Miami). Are these fairs competing? Not quite. They don’t happen at the same time,[8] and don’t offer quite the same type or amount of wares. Design Miami/ and TEFAF are big ships, but they still carry relatively little contemporary jewelry: You’ll attend because you are also invested in what’s going on in design or art. Collect, Collective, Frame, and SOFA cover similar mixed craft territory (although Collective puts a much stronger emphasis on design), but the two older ones (SOFA and Collect) seem to have lost part of their appeal for contemporary jewelry galleries. These participated when there was no alternative, but may now be reluctant to present cutting-edge work in a fair that has become comparatively mainstream (SOFA) or to travel to London when they have something closer to home, or are pursuing online selling strategies.[9] At the time of writing, Frame continues to be the most exciting destination for specialized collectors: They know that behind the relatively small group of galleries at Frame beckons a citywide glut of exhibitions and studio visits.[10] None of the other commercial fairs can boast of such rich offerings. I am watching out for how Collective will develop: New York came to contemporary jewelry late in the game, but it looks like it wants to seriously establish itself as an East Coast arts/craft/design mecca. The first edition of TEFAF—a European concern that is trying to find a new wind on American soil[11]—will tell us how likely it is to succeed.

COMMERCIAL FAIRS FOR MAKERS

|

JOYA, SPAIN |

SIERAAD, AMSTERDAM |

Meanwhile, in Amsterdam and Barcelona, two commercial “fairs for makers”—i.e., that rent booths to artists, collectives, and schools only—have been showcasing emerging practices for a while, and have steadily grown in size and reputation: Between 2002 and 2015, the number of Sieraad visitors has multiplied threefold, while Joya, founded in 2009, has gone from a 14-exhibitor affair to a program with seven people’s choice awards, 46 individual artists, two collectives, 10 schools, four galleries, 20 selected artists for the Enjoia’t Award, and, finally, 75 artists represented in 22 “off” JOYA galleries. (Attendance also tripled, from 1,200 to 3,300 visitors.)

Makers’ fairs do not seem to attract the same sort of crowd or show the same thing as gallery fairs: Joya and Sieraad clearly serve makers (and not galleries), are easier to get into (even though demand becomes higher every year), and their emphasis on emerging talent means that they gladly partner up with schools and workshop collectives. That makes them an ideal place for looking at young work in the context of its production.

Both fairs have also been nimble at choosing themes or geographical emphases for each edition. Joya has made a point of showcasing Latin American and Asian work, and of turning itself into a platform for “Southern” work. Paulo Ribeiro, one of the two organizers, says: “The main singular essence of Joya is the promotion of Mediterranean and [such] southern European artists as Spanish, Italians, Greek, Turkish, Portuguese, and French, combined with Latin American artists that promote their work in Europe.”[12] This specialized emphasis reflects the surge in fair numbers: There is a call for distinctive features. The mood in Barcelona was vibrant when I visited in 2015, and, for the first time perhaps, I felt as though I was partaking in an event that stood as a credible and distinct alternative to Munich Jewelry week. I’m curious to see whether they will hold to their mission, and how collectors will respond to it.

2. EDUCATIONAL AND CELEBRATORY FAIRS

|

SNAG |

ZOOM |

AJF has often reported on SNAG, and occasionally partnered up with it: It’s the meeting point for studio makers in North America, drawing up to 1,000 paying visitors to its yearly four-day seminar. The roving event is the only case of a primarily educational platform that bloomed into a “jewelry week”: Its plentiful program has long since diversified from a conference into a dense program of workshops, formal and informal talks, and exhibitions, with a particular emphasis on professional development. (It’s worth noting that SNAG exhibitors include a number of tool suppliers, alongside Charon Kransen’s rich bookshelves). Transmission through hands-on practice and post-graduation networking are key, but the recent development of a substantial exhibition program—both on site and off—is turning SNAG into an interesting proposition for jewelry academics and collectors—not just for students and alumni.

The event’s emphasis on nurturing the traditional, craft-based studio jewelry model has made some room for Zoom, which is clearly modeled on SNAG, but whose organizers and participants channel the rise in academic, cross-disciplinary practices. The most recent event was orchestrated by Michael Bernard, held at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, and included a short but intense inquiry on installational jewelry practices by AJF contributor Courtney Kemp. Zoom celebrated its second edition in 2016 (the first edition was masterminded by Nicole Jacquard, at Indiana University), but it’s not yet certain whether it will continue. Both SNAG and Zoom are primarily directed at students, and despite nuances in their outlooks on craft, they provide a similar mix of talks, workshops, and internally juried exhibition and “off” events, all mostly noncommercial and artist-led.

|

LEGNICA FESTIVAL SILVER, LEGNICA

|

TRIENNALE DU BIJOU CONTEMPORAIN, MONS

|

SCHMUCK and TALENTE, MUNICH |

Alongside the two aforementioned educational North American affairs, three European cities have become gathering points for the celebration of gold- and silversmithing, and contemporary jewelry in general: Mons, Legnica, and Munich. All three are invested in selecting “winners” and giving out prizes: These accolades are rooted in tradition—they are the tradition—and lend these three events their authority.

Mons’s Triennale du Bijou happens every three years, and consists of a dialogue with two other countries, to which Belgium plays host: That has ensured a form of diversity and a triangular cultural conversation that defies the more conventional binary system of host + guest. In 2014, WCC-BF invited Italy and Finland, and, for the next edition, in 2017, Sweden and France will be Belgium’s guests. (One wonders why the selection of guest countries should remain exclusively European, given the “W” in WCC. But maybe it’s like the United States’s “World” series). One or two curators from each country are invited to collaborate with the WCC’s own, and put together a large exhibition of 80 artists. Talks, workshops, and the usual “off” exhibitions are there to spice up the main dish.

Like Mons, Legnica is a relatively small city, which nonetheless has done very well by its Legnica Festival Silver, and is steadily becoming more international (Stephen Bottomley reported in 2014 on its seminar—which did not impress him—and the exhibitions—some of which he loved). Neither Legnica nor the Triennale were conceived with collectors in mind: They mean to celebrate good work, and do so on their own terms. The Belgians choose a laureate for each edition, and the Poles award one kilo of silver grain to three designated winners, in a gesture that’s as imperial as it is simple: You are good, go make some more. Both have seminars, and “off” shows where jewelry is for sale, but one senses that they primarily operate as cultural mixers between local and international makers, and then between that hybrid group and a local community of visitors.

The last (and oldest! and most famous!) example of celebratory fair is Schmuck: shorthand for a three-part juried exhibition system comprised of Talente, Schmuck, and Meister der Moderne.[13] The three shows correspond to three career “stages,” recognized as distinct by an organization that believes in the slow maturation of craft skills. Launched in 1959, Schmuck set the global standard for international juried exhibition through longevity, rigor, and excellence. More recently, it has held a singular position at the core of a pulsating “off” program that it unwittingly gave birth to. Schmuck benefits from the presence of Frame around it, and they both benefit from the 70+ museum and artist-led exhibitions taking place in the city of Munich. Self-organised to the core, these “off” events started getting more visibility three years ago thanks to the efforts of the promotional organization Munich Jewellery Week (MJW), the brainchild of magazine Current Obsession (MJW started by providing visitors with a much needed map of exhibitions and events; they are now gearing up to become a supporting logistical body for first timers.) You, dear reader, will have recognized here ingredients from other jewelry events. But Munich simply has them all, and has thus become both a rallying point for dealers and collectors and a creative incubator for the hundreds of students and educators who converge there every year. It’s unlikely that its dominant position will be duplicated by any other fair soon, but, as this briefing shows, this is precisely not the point: We are at a happy stage of global diversification. My own bet is that, moving forward in a more crowded field, those events that play up their singularity—via an alliance with another field, or a good balance between international and local, site-specific and site-resonant projects—will succeed better.

3. MISSIONARY FAIRS

|

ART JEWELLERY, STOCKHOLM

|

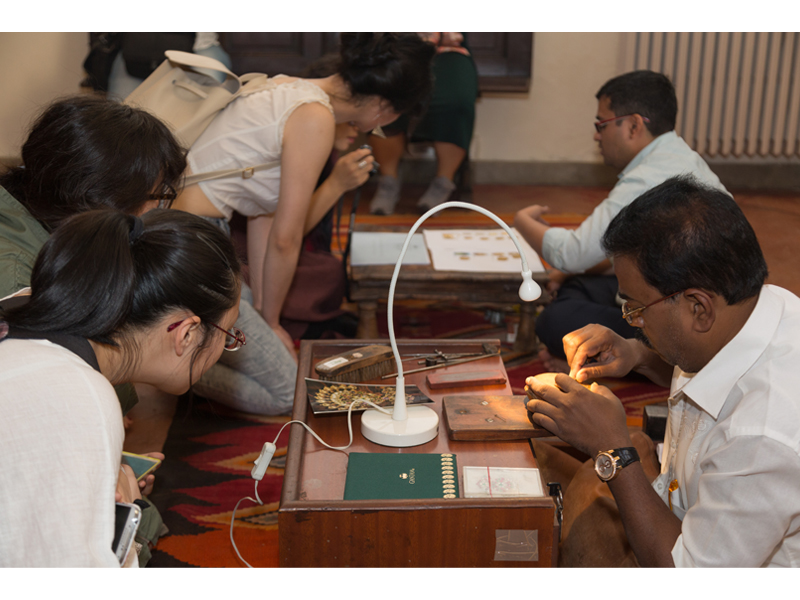

FLORENCE

|

JAM SESSIONS |

|

ATHENS JEWELLERY WEEK, ATHENS

|

MELTING POINT, VALENCIA

|

RADIANT PAVILION,

|

|

PARCOURS BIJOUX, PARIS |

The “missionary” model is defined by a few constant elements: Motivated by a desire to create awareness on a local level, it is shaped in the form of an urban takeover and overwhelmingly initiated by artists, with the support of a cast of commercial, educational, and institutional partners. It is a strategic weapon, meant to turn the lack of exposure of a local community of makers into a promotional opportunity for the field at large. Its glorious predecessor is Ars Ornata Europeana (1993–2007): a transnational “meet” masterminded by artists (and, initially, for artists) that took place every two years in a rotating European city. Some of Ars Ornata’s ingredients survive in its various contemporary avatars: The missionary model favors spread over concentration; it is inclusive, and dedicated to artists’ voices; it is rooted in a philosophy of collective action, and keenly supportive of outreach and educational programs.

Its self-propelled nature also means that the missionary model is more nimble: Some programs, like Play Jewellery and Radiant Pavilion, have serious thematic ambitions, which are given some traction by the organizers’ wide professional networks. In fact, the missionary fair is typically exempt of the decision-by-committee of either commercial fairs or educational ones, and can reflect the special interests of the organizer(s) and channel the specificity of a local scene. Susan Pietszch’s cross-disciplinary approach is palpable in the Play Jewellery program, just as Chloë Powell and Claire McArdle’s is in Radiant Pavillion, which seems to have channeled the inclusive thinking of Roseanne Bartley, Kevin Murray, and Manon van Kouswijk.

It is probably useful, when deciding which to visit, to pay attention to missionary fairs’ various development phases: First editions aim to create addiction through a one-time, massive contemporary jewelry injection. If the organizers survive this phase, they will try to turn the initial splash-out[14]—largely leveled at local jewelry non-initiates—into a sustainable model that makes sense for international participants and visitors. The 2016 Athens Jewelry Week, which showcased 11 exhibitions, one day-long, international seminar, and a workshop, was “an important moment for contemporary Greek jewelry”:[15] It gave contemporary jewelry a visibility in the capital that it never had had before. But it also “set the stage for [Greek jewelry’s] international debut”:[16] Next year’s edition will align itself with Documenta, which is sure to bring a large crowd of art jet-setters to Athens.

Indeed, for their second edition, organizers can be more selective (more people will apply). They might charge a slightly higher fee (having learned the first time around how much time these things take), and look for more upscale or desirable venues. Five of the seven missionary fairs are entering that phase, and they generally have done so with cultural synergy in mind: Athens has paired up with Documenta, the Parisian Parcours du Bijou with a major jewelry show at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, while the Stockholm Jewellery Week is supported by a groundswell of museum participation. These alliances are necessary, and add to these projects’ cultural cred. This is a particularly exciting moment: A huge number of next year’s jewelry exhibitions will in fact be enmeshed in citywide projects that are already thinking in terms of long-term sustainability.

The reports sent to me by their organizers measure the missionary weeks’ success in terms of exhibitors’ satisfaction, the enormous esprit de corps that these voluntary mega-projects always generate, and the excitement and gratefulness of visitors, from within and without, who come to meet an energized community of makers, dealers, and their international friends. These certainly are soft metrics, but accounts from Melbourne, Tokyo, Paris, Athens, or Valencia speak of the rewards of citywide treasure hunts celebrating their own ephemerality, and the joyful unlikeliness of some of the venues: a butcher’s shop, a fan museum, a pedestrian lane. Missionary fairs are generous, inclusive outfits: They aim to please locals but promote a healthy competitions between hosts—who want to make good as organizers—and their guests. They can also have sound commercial prospects: I expect that as they celebrate their second year, these events will attract more for-profit efforts—and who knows, maybe foreign galleries will realize one day that doing a pop-up in Athens, Florence, or Paris is not such a bad idea…

The future is bright, the future is temporary

I know and like the fact that in three years, a similar report will paint a different picture of JEs around the world. The jewelry market will continue to move according to the trends—real or imagined—that push dealers, collectors, and artists into certain patterns of interaction. To understand where things are going, and whether JEs are a good destination, I’ll be asking myself—and trying to answer—the following three questions:

If fairs take over the jewelry scene as the main interface between makers and the public, will they allow us to think through the complexity of contemporary practice? Commercial fairs don’t, and won’t: They’re a point of sale that doesn’t make much room for slow consumption, or the sort of thoughtful overviews that juried, educational fairs often produce, or for intensely curated shows that are the staple of missionary shows.

So for a fix of high-end, blue chip jewelry, I’ll head to Miami. But if I want the quirkier kind of projects—those involved projects that make me think, and give me a sense of where the field is going, I’ll fly over to Melbourne, Paris, or Athens.

The next question is how dealers will adjust to this roving, temporary market. Early adopters like Lachaert, Ornamentum, or Sienna Patti unsurprisingly come from peripheral towns: They always have needed to work more, travel farther, and communicate better than their metropolitan colleagues to reach collectors. Ornamentum, located in the small town of Hudson, New York, was a jewelry pioneer at Design Miami/. And yet paying the rent on brick and mortar and the hefty costs of attending fairs is a punishing proposition: If fairs become a hegemonic platform, a number of smaller galleries will no doubt be decimated, or may have to become more local in their ambitions, and rethink the way they lure visitors and clients in.

The last question is whether jewelry fairs—commercial or otherwise—will continue to make sense in the long run. They’re an incredible concentrate of artistic creativity and occasional curatorial daring, but they’re also a lot of work for visitors: Getting there, staying there, and walking around may not be all that alluring to the smartphone generation, specially if the work on display is also available online. Discretionary income they may have, but they’re also used to getting accessory-sized things shipped to them. Some art fairs have addressed this issue by commissioning site-specific work that can’t be seen elsewhere, and by strengthening their “live” programs (lectures and performances, but also dinners and parties): I imagine this is one way forward. Another exciting model is Amsterdam’s Unseen photo fair, an event that only showcases work never exhibited before. I’d travel to that…

Useful links:

Athens Jewellery Week

Collect

Collective Design Fair

Design Miami/

Florence Jewellery Week

Joya

Legnica Festival Silver

Melting Point

Parcours Bijou

Radiant Pavilion

Schmuck

Sieraad

SNAG

SOFA

Talente

TEFAF

Triennale du Bijou contemporain

[1] I would like to acknowledge—and thank—by name my informants around the world: Grainne Byrne (Collect), Sarah Medford (Design Collective), Andreas Ritter and Frank Neidlein (Frame), Paulo Ribeiro (Joya), Astrid Berens (Sieraad), Gwynne Rukenbrod Smith (SNAG), Nicole Jacquard and Michael Bernard (ZOOM), Nelly Van Oost (Triennale du Bijou), Wolfgang Lösche (Schmuck and Talente), Inger Wästberg (Stockholm Jewellery Week), Demitra Thomloudis (Athens Jewellery Week), Giò Carbone (Florence Jewellery Week), Heidi Schechinger (Melting Point), Brune Boyer & D’un Bijou à l’Autre (Parcours Bijoux), Susan Pietzsch (Play Jewellery), and Chloë Powell (Radiant Pavilion). At the time of writing, the organizers for TEFAF (New York), SOFA (Chicago), Basel Design week (Miami and Basel), and Legnica Festival Silver had not responded to my questions. Information concerning their fairs was gathered through online research.

[2] The first edition, organized under the aegis of Atelier d’Art de France, was called “Circuits Bijoux.” The second edition is organized by the same body—D’un bijou à l’autre—minus the funds of Atelier d’Art de France.

[3] Design Miami/, founded in 2005, opened its doors to Ornamentum in 2008.

[4] As quoted by Judith H. Dobrzynski, Can Maastricht Take Manhattan?, The New York Times, Sept. 26, 2016.

[5] Those pressures are described in some detail by Sarah Douglas’s article, “It Was Like Someone Turned The Faucet Off”: Lisa Cooley On Closing Her Gallery,” in ArtNews, August 29, 2016.

[6] Artistic: “Work exhibited must be present in significant private collections.” Commercial: “It is deemed detrimental to the quality standard of the event to show or sell works below £500.” Sarah Medford, in email to author, August 17, 2016.

[7] See http://www.culturewhisper.com/r/article/preview/4166.

[8] The one exception is Collective and TEFAF New York, whose dates coincide for strategic reasons.

[9] No-gram is the example I have in mind: Theirs is currently the most sophisticated example of an online contemporary jewelry sales platform. They are also doing this against the popular wisdom that one can’t sell contemporary jewelry online. But they are—and that business model is certainly less expensive than a fair.

[10] On average, over the last three years, the MJW “off” program listed 80+ exhibitions and events dedicated to contemporary jewelry. That’s on top of Frame, Schmuck, Talente, Exempla, Meister der Moderne, the Handwerksmesse’s numerous demo booths and jewelry stands, and the city’s plentiful museums, art galleries, bookstores, and beer halls.

[11] Dobrzynski, Can Maastricht Take Manhattan?

[12] Paulo Ribeiro, in an email to the author, August 16, 2016.

[13] Talente selects works by artists, designers, and craftspeople aged 35 and younger. The popular understanding is that Talente is a preamble to more mature greatness—and selection for the jewelry-only Schmuck exhibition next door. The distinction, in recent years, has become a little wishful, as work selected for Talente regularly equals Schmuck selections. Meanwhile, Meister der Moderne showcases the work of a single “master” in a series of dedicated showcases inside the Schmuck pavilion.

[14] Radiant Pavilion, in its first edition, fielded 57 self-managed events, featuring 217 artists from 17 countries in 51 different venues (full program). Meanwhile, Parcours Bijoux boasted over 70 shows (including 3 museums shows) and a two-day seminar.