The news of Karen Pontoppidan’s nomination as the successor to Otto Künzli at the head of the Munich academy’s jewelry department was viewed—with excitement, surprise, joy, and worry—as a tidal change. She was picked from a wide cast of artists with excellent reputations, each of whom would have brought something singular to the Akademie, and shaped the next generations of Munich alumni in a very different way than she will.

To this outsider to the selection process, her nomination indicates a desire on the part of the selection jury to put pedagogical acumen on a par with artistic recognition, thus challenging the idea that art teachers should be artists first, and educators second (if at all). Pontoppidan does have a solid track record as a jewelry artist, but she is not as recognized as some of her peers as an artistic “leader.” But as the interview below makes amply manifest, being a “leader” is antithetical to Pontoppidan’s teaching philosophy: She means to challenge authority, if that authority does not posit the speaker’s truth as relative.

Meanwhile, she has hopped from promotion to promotion as an educator, is extremely appreciated by students, and takes teaching very seriously. Picking her may simply have had to do with the fact that other centers of educational excellence now exist in the world (South Korea’s Kookmin University, New Zealand’s Handshake program, North America’s Cranbrook Academy). A long and successful teaching experience and an inclusive approach to education may be safer guarantees for Munich’s continued preeminence in the field.

When I asked her for an interview, my primary goal was to get a fuller picture of Pontoppidan’s approach as a teacher, and provide the “new head in Munich” with a platform to share what she would about her method. I got more than that. The interview, conducted live in February 2016 and then via email over three months, shows how both her artistic output and her teaching are governed by urgent questions about normativity, leveled at a field that often confuses diversity with inclusiveness.

Part I

Benjamin Lignel: How can one teach contemporary jewelry to students?

Karen Pontoppidan: My concept of being a teacher is based on the fact that students are already artists before they start their education. My task is therefore to support them in developing deepened insights and a professional attitude toward their chosen profession. My starting point for tutorials in general is the intention of the individual student, which I use as a lens for tutorial and reflection.

A key element in my teaching is the awareness of the relativity of one’s point of view. There is not one truth—for example: that of the teacher—therefore every step in the process must be seen in context.

Incoming students might feel stressed by the fact that I do not posit my experience with jewelry as a kind of solution for their search, but instead encourage them to question my solutions and to question the truth spoken by more experienced generations. I am, however, convinced that each generation of artists has specific issues to deal with, and the current students will have to develop insights that might not correlate with the insights of previous generations. All incoming students at the academy do have previous educational/professional experience, which should help them contextualize jewelry, and most students are between 24 and 28 years old when they start at the academy, so they benefit from their previous life experience.

One of the characteristics of the Munich academic system is that there is no actual teaching. There are, however, regular encounters with students: Every Wednesday, we have a class meeting, where one student presents her or his work, which then is discussed for a couple of hours by the group.

Tuesday afternoons, we sometimes schedule thematic discussions. The subjects are varied, and can be basically anything which the students or I find relevant in the present moment, for example “Professionalism and Galleries” or “Purpose of Jewelry.” I will normally introduce each session with a short presentation, which serves as a starting point for a collective discussion. It is however not mandatory for the students to participate in this kind of event, since the education always focuses on the individual development of each student’s work, and therefore the students must decide what is relevant to their current pursuits.

I do not give the students assignments, or engage in other ways in “top-down” lecturing. In the academy system, there are no grades, or exams, or credit points. Only at the beginning and at the end of the education does an evaluation by the professors take place: first, in order to be accepted, and last, in order to be awarded the diploma.

The quality of this system is that each student will face the challenges and issues necessary for their development as an artist, at the moment when they are relevant for their work, and not as something that is forced upon them through a course schedule.

How well do you think this system compares to others?

Karen Pontoppidan: I personally believe that there is no better learning environment than the one of the academy, for several reasons: It offers an open frame for individual aspirations, the study is free of charge, it gives plenty of time to nurture artistic development, and, in the case of the Munich academy, a privileged location in a hub of contemporary jewelry gives students many opportunities to experience the reality of working in the field firsthand. The students can choose to finish and complete their diploma after three years—but most of the students want to stay longer (up to six years), which for me is a good indication of the freedom and opportunities the education offers to them.

Since the students are not given assignments or otherwise confronted with tasks, they, from the very beginning, work independently on the subjects of their choice, and thereby they are responsible for time management as well as for driving their process further. In this way, the education mirrors the reality of working as a professional; the only difference is that students are embedded in a very supportive environment.

How does your own teaching platform differ from, say, Ädellab, where you taught for nine years?

Karen Pontoppidan: A main difference is that the teaching staff is much smaller here. Except from Matthias Mönnich, who is the workshop-leader, I am currently the only teacher at the department. This fall (2016), Jasmin Matzakow just filled a half-time position as assistant professor, but in comparison, at Ädellab I had a team of six teachers working with me on education.

Another difference is that I have less influence on budget decisions at the academy than I used to at Ädellab. For example, we hardly have a budget for guest teachers.

So in general it is a lonelier position. The fact that I am on my own means that there is only one so-called “expert”—and as you know, I don’t favor a “single truth” environment. Having a team with different competencies within the education, as I did at Ädellab, made it easier to communicate the wide range of jewelry approaches to the students. Here at the academy, the students have to visit other departments in order to widen their perspective beyond what I can offer.

Why did you become a teacher in the first place?

Karen Pontoppidan: Like many jewelry artists, early on I experienced that my work was not met with enough critical feedback or with enough financial success. I decided to support my practice through teaching, and this had two benefits. Firstly, I could create without the burden of having to relate my artistic approach to the market. Secondly, I realized when I started teaching that the social interaction and the critical discourse with the students is a source of nourishment: I found myself permanently challenged and inspired by their questions. I would claim that the discourse with the students also makes me a better artist. It is not actually their artistic work which inspires me; rather, it is the challenges of being a teacher that makes me define my own artistic practice more precisely.

From the very start of my career as an educator, I made a clear distinction between my own creative practice and that of the students. I work with the students in the awareness that I am paid to support their practice. The students are of course welcome to show interest in my work, if they find it relevant for their development, but I don’t usually bring my work to class. I emphasize a system where the students do not “follow the master,” since I don’t find it a relevant or contemporary approach to education.

How do you think your educational model differs from that of your predecessors—if indeed it does?

Karen Pontoppidan: In my opinion, one of the qualities of the past generations of professors in the jewelry department at the academy has been that their approaches were anchored in the cultural reality of their time. Their approaches were relevant for the development of independent artistic positions, which would be reflecting the current discourse of the surrounding society. My goal is the same. What is different in my teaching methods, in comparison to my predecessors’, is therefore rooted in the differences between the developments of today’s society in comparison to the developments of society 20, 40, or 60 years ago. Clearly issues of gender, class, and ethnicity need to be included today. Also a wider range of theoretical discourse is present. Or, to give another example, as much as economic prospects have changed for artists within the field, so must education react to a changing market.

How do you think the “independent artistic profession” model has evolved over the last 20 years, and how might it evolve moving forward?

Karen Pontoppidan: I think it is important while thinking about artistic professions to distinguish between the developments of artistic professions in general, and the changes within the specific field of jewelry.

In general, I think it is necessary for contemporary artists to fight against the rather romanticized image of “the artist” which has been promoted and exploited by many in former generations. I hereby refer to the artist as some kind of sensing genius, living in HIS own universe, in which the private and the professional are seldom separated. Today’s artists need to be multitasking in a different way. They need to be strategic, have a sense for business, speak several languages, and so on. They cannot afford to focus only on making art; they need to develop homepages, develop their lecturing skills, etc. Of course this is a general observation. In individual cases the emphasis might be placed differently and the artistic careers still develop well, but the expectations on younger artists today include the issues mentioned above.

The current situation within the contemporary jewelry field also demands the artist’s awareness. I recently had a gallery owner explain to me what my task, as a professor, should be. I find this very interesting, since it exemplifies the ongoing power negotiations within the field. In times where such power battles are so apparent, artists need to be able to contextualize their work and their professions, otherwise the art work will suffer under the political maneuvers of the “extended field players.”

I would like to clarify my thoughts on this matter The field needs a vivid discourse, and in order to achieve this, all positions within the field need to speak out—gallery owners, art historians, philosophers, collectors, curators, and artists. In this process, it must be possible to fail occasionally, as for example happens when art historians start writing manifestos on behalf of artists. However, in order for all positions within the field to be heard, artists need to be recognized as what they are: the most essential and front-developing players within the field. It is therefore crucial that the skills of the artist be developed accordingly. This is what I aspire to at the moment.

Would you ascribe—and this is a sexist question, whichever way one puts it—your sensitivity to relativity to the fact that you are a woman?

Karen Pontoppidan: I do—being a woman makes one more sensitive to the relativity of truth, and also to the power structures that surround us. In general, it seems to be the privilege of the ones designated as “the other” to be able to comprehend the hidden power structures of society. A paradox of our culture is that women—half the population—still figure as “the other.”

Within the field of jewelry, this is by no means different. If we make a moderate estimation; more than 80% of European jewelry artists are women, but this number is not reflected in museum collections, or in jury memberships, or in the statistics of winning awards. And if we would examine our field in relation to the known disadvantages of minorities in society, much worse statistics would probably become manifest.

I therefore believe that being a female artist has forced me to develop other strategies than those my male colleagues have needed. And it has made me more aware of normative thinking structures.

The reason I called the last question “sexist” is that it presupposes that there are masculine and feminine ways to do things, and that that behavior is tied to our biological sex. But thinking in terms of gender implicitly undermines that link, and posits gender as something that is socially produced. Do you agree with this view, and do you think that jewelers can contribute to that conversation?

Karen Pontoppidan: Absolutely, but it is important to keep in mind that on most levels of society the concepts of gender and sex are seldom separated, and since the idea of gender relativity is quite new, it can be difficult to comprehend its potential and consequences. But exactly because body appearance is an important means of confirming, or challenging, normative gender perspectives, I believe that jewelry could become a very powerful medium to disrupt the existing structures.

There is very little contemporary jewelry that engages directly with the concept of gender. Why do you think this is the case?

Karen Pontoppidan: I often experience, when I use the words “gender” or “normativity” in lectures, that my audience rarely has a clear understanding of the concepts behind the definitions. The concepts of gender and normativity are apparently not that present as subjects of urgency in central Europe and tend to be confused with the question of equal rights. It is therefore not surprising that few jewelers embrace these themes in their artistic work, since a deepened awareness is generally not present.

Part II

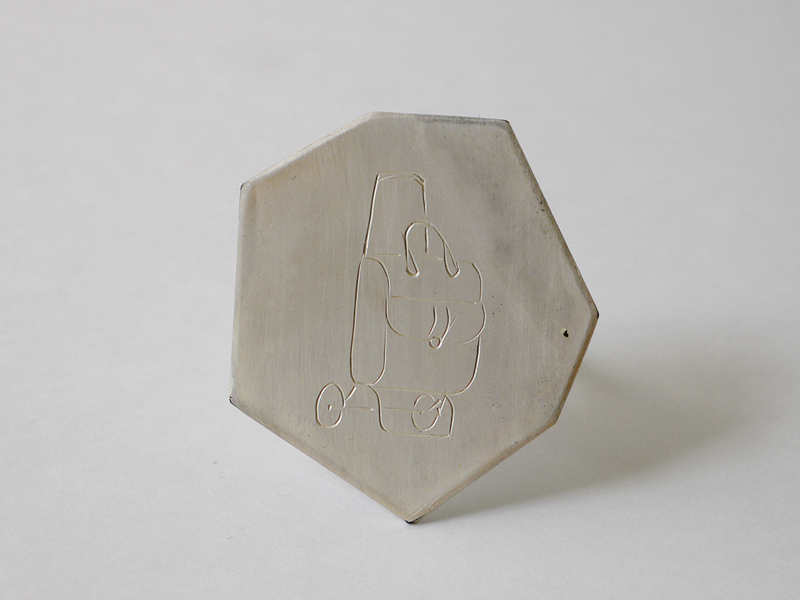

I would like to take a leap from here, and discuss your work—two aspects of it in particular. One of them is what I would call the keyhole view of the domestic and familiar. A number of your works, made over the last 20 years, feature simple—occasionally childlike—sketches engraved on metal. These sketches are innocuous: a shoe, a shopping cart, a car, a steam iron. Maybe because I have edited a book on her work, these remind me of the cartoonish drawings of Ida Applebroog—an American painter who has worked around the representation of domestic violence since the mid 70s. But this is one of many possible connections. So, first of all, what genealogy do you, personally, place your drawings in?

Karen Pontoppidan: In the series of work you refer to (Untitled,1997–2007), I investigated normativity within Western jewelry traditions. The motifs engraved on the pieces were chosen for their ability to challenge jewelry with unusual or disturbing narratives. I believe I was influenced by the work of the German artist Rosemarie Trockel during that period, but I can relate to the association with Ida Applebroog’s work, too, although I was not familiar with her work at the time.

In retrospect, my awareness of the relevance of my drawings was in some way limited, as I struggled to find a language for myself outside the possibility of making jewelry. Although now I can formulate the discourse I was striving for also in thoughts and words, in that period I relied mostly on my hands.

Can you tell us a little about the specific range of things, and people, you have represented in these sketches? There is something singular about the economy, and framing, of these vignettes: They often seem to freeze-frame a larger scene (something is always happening next). This is both very evocative and quite dry. Isn’t there a danger that viewers will just take these images at face value—and not reconnect them to the wider context they (may) belong to?

Karen Pontoppidan: In all my works up to today, the main interest has been to investigate an aspect of what could be described as “the other.” In this case it refers to the otherness of certain objects, animals, people, or situations within jewelry. The dryness of the images, or the often out-of-center placements of my drawings, are a means to disturb the habit of celebrating motifs, which is often found in jewelry.

Since I am aware of my own limited perception of things, and often also of my limitations in comprehending artistic work, I am seldom disappointed if viewers do not immediately relate to my intentions. Clearly, as an artist, I have an intention—a story—I want to communicate, and it would be fantastic if everybody would understand, but I also believe it is in the nature of working with the subject of normativity that only some will understand it immediately. I have often experienced that customers will relate to and start buying my work years after their first encounter with it.

These drawings, because of their simplicity, seem to avoid a specific stylistic signature: They are everyone’s and no one’s. How does that help you investigate the question of the “other”? Is this a way to create a form of verfremdung, or alienation?

Karen Pontoppidan: The drawings are “motifs placed on jewelry.” They represent objects, people, etc. Like pictograms, they are not made with any artistic intention besides that of serving the jewelry piece. Photos inspire some of the motifs, some are freehand drawings, and occasionally I have used drawings by others as a starting point for a motif.

By using different sources, I avoided creating an artistic handwriting in the drawings, and by reducing lines to the minimum needed to be recognizable motifs, a certain kind of loneliness or alienation takes place. This is important to me, since my intention was to investigate “otherness” within jewelry. The motifs—for example a toilet—are hence not placed in “their” scenery—like a bathroom—but stand alone, and thereby create a contradiction to the jewelry piece.

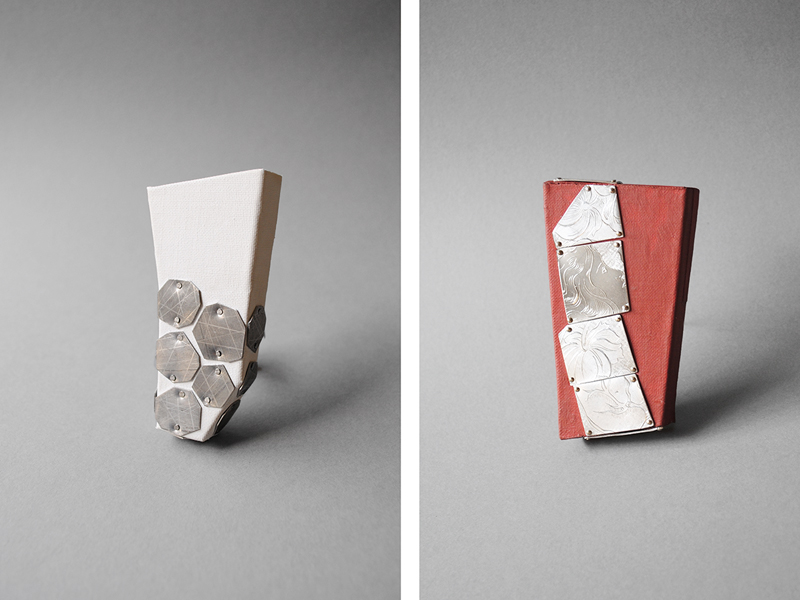

A second aspect of your work that I’d like to speak about is “context.” This obviously refers to your 2014 series of outsourced brooches, but also to your more recent Cash series, in which you rolled down silver coins and painted them yellow. Both strategies—outsourcing and painting over precious metal—undermine some of the core values of craft.

Let’s start with outsourcing: Why were you interested in having your work made by others? Does that have to do with your reticence vis-à-vis the cult of the author? (But if so, why sign them?)

Karen Pontoppidan: Context is the second part of the trilogy Canvas, Context, Cash, where I investigated concepts of craft in relation to the fine arts.

In the group Canvas, my intention was to use my goldsmithing background as a lens for decision-making. After I finished the Canvas brooches, I wondered to what degree, during the working process, I had given my inner goldsmith precedence over my artistic intentions. Although I absolutely love the making process, as an artist I am convinced that the making in itself cannot and should not be the aim of my work. I therefore decided to continue examining the material canvas in jewelry, but with a process that excluded me from the manufacturing.

Signing the brooches, as my only act in the production, was a slightly ironic blow toward the art/craft discourse. And, yes, this includes a blow toward the cult of authorship and artistic handwriting.

“Collective authorship,” “collaboration,” “participation” are buzzwords in the art and craft worlds, but they don’t have the same implication depending on how one defines their practice. Why do you think they are popular in craft circles, and what can we learn from them?

Karen Pontoppidan: My focus is always on the objects created. The author is the source from which the objects come, but the objects must be able to exist and function without the author. Whether an object is made by a group or by an individual is therefore of no great significance. Either way, the author/authors of objects must carry the artistic, the environmental, and the ethical responsibilities for the product.

Important for me is a general change in perspective: Instead of evaluating contemporary jewelry as a matter of personal artistic expression, I prefer to view contemporary jewelry as an important cultural phenomenon, and therefore cooperation is as valid as individual work.

But in the process of questioning stale concepts of authorship, collaborations can function as a very meaningful tool.

In your Cash series, your artistic gesture hinges partly on erasing the face value of the coins you use—in effect flipping them into the value system of art. This is reminiscent of other defacements: Otto Künzli’s Change, Lauren Tickle’s Currency Converted series, or Robert Rauschenberg’s Erased de Kooning Drawing. I suspect your motivations were quite different from theirs. Why are you interested in playing with value systems?

Karen Pontoppidan: The series Cash is the last part of the trilogy mentioned above. The silver coins I used represented monetary value, as this series intended to comment on the economic imbalance within the art/craft paradigm. My intention with the work was specifically pointing toward the art market, and did not focus on the political power structures that coins also represent. Wearing coins as jewelry mainly for their monetary value has a long tradition, in particularly outside of but also within Western culture. For me it was attractive to quote these traditions in my work, since the monetary value is simultaneously a myth and a burden for jewelry today.

Where do you see the future of jewelry?

Karen Pontoppidan: I think we are at an interesting turning point in the field. Most contemporary jewelers like myself have a background in learning craftsmanship. Most of us have then studied at university level, where our teachers have developed their careers from a similar background. The field therefore has a strong connection to craftsmanship, which to some extend has become a burden. The lack of jewelry-specific theory by professional writers adds to this, and creates a gap between artistic practice and the understanding of jewelry as a cultural phenomenon. Based on such considerations, I find it urgent to contextualize our field in a broader sense, in order to understand and question our own history. By doing so, I believe great potential will reveal itself.

I think we also need more honesty about the fact that not all makers within the field of contemporary jewelry have the same goals and ideals. Some makers are committed to material aesthetics and wearability, others are making jewelry investigations, where references to the body are more important than actual use. Within the field, there are people striving to make a living through their work, and others who find such considerations irrelevant for their artwork. Some jewelry artists orient themselves toward the design field, others toward jewelry traditions and craftsmanship, and yet others strive for the fine art market. Claiming that we are all moving together in the same direction is simply wrong. I think that a maker needs to define who she or he wants to be. The field would gain strongly from clarifying positions—not hierarchical, but different, equally valuable positions.

Can you say a little more about this? Does this have to do with choosing a market? Are you suggesting that your role (and by extension, that of all jewelry educators) is to help students distinguish between genres and settle for one?

Karen Pontoppidan: For me, it is mainly about defining yourself as a professional of a field, instead of just being a “maker of something.” Choosing to be a jewelry artist by profession includes developing a vision for your professional life, from which fruitful choices can be made according to your aspirations. A professional vision must, in some way, relate to the market, as well as to the specifics of an artistic talent and to other influential cultural realities.

The issue of defining positions has become urgent to me, because the makers within the field of contemporary jewelry for sure have very different needs depending on their professional aspirations. Whereas for some professional careers craftsmanship or technical innovation are crucial aspects, for other artists theoretical discourse on the Everyday or object-subject relations might be much more urgent. Some artists strive to develop wearable, fantastic jewelry for customers, other artists strive to provoke or research or change the world, and these different directions deserve to be supported better. It is not just a question of two artists taking different paths: These different directions should be differentiated also within the grant systems, jewelry competitions, curatorial work, etc. I believe the field of contemporary jewelry would gain a lot if we would stop comparing “apples” with “pears,” and instead focus on developing the depths of both.

Sometimes, when I talk about defining different positions, people believe that I wish to create “boxes” in which their artistic freedom will be limited. But freedom, from the very beginning, only exists within defined spaces. No matter how big a “freedom space” might be, borders are present, which society has created. My wish is to analyze the different positions, and therefore strive for a deepened understanding of the given limitations and borders. Through this understanding, we can not only improve education for individuals but, more importantly, we can redefine freedom spaces and fight for our artistic merits.

Thank you!

INDEX IMAGE: Karen Pontoppidan, 2015, photo: S. Dell