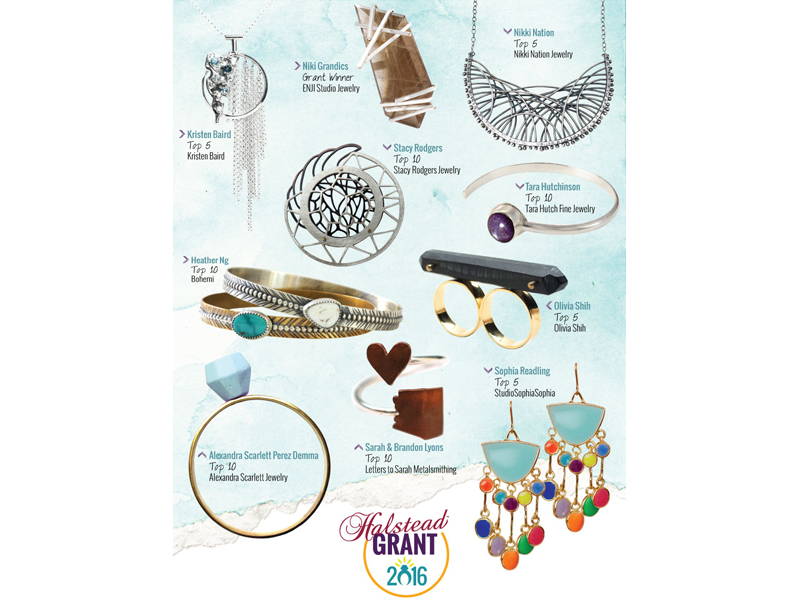

Halstead, a family-run wholesale importer and distributor of jewelry findings, and a corporate sponsor of AJF, just announced the 2016 winner of its yearly award to be Niki Grandics. AJF’s editor takes the opportunity to catch up with company president Hilary Halstead Scott to ask her why she is so keen on growing the next generation of jewelry entrepreneurs.

Benjamin Lignel: Halstead is a family-run business, kick-started in 1973 on the strength of Tom, your father, getting orders for strands of African trade beads he’d brought in to show his colleagues at work. Forty-three years later, the company employs 30 people and is selling chain and findings all over the US. One imagines that your parents’ accidental encounter—and love affair—with beads was matched by an entrepreneurial drive. Was that the case? What sort of challenges did they face to grow the business?

Hilary Halstead Scott: Indeed, my parents were a great team with exceptional entrepreneurial talents. Passion for jewelry in anthropology was certainly one motivator for the business. But the biggest driver was a passion for family and building something for the future; not just for our family but all of the small-business families that make this field so unique. That concept of supporting family businesses in the trade is still at the core of our mission.

Halstead would have never survived without the strengths of each of my parents. My father is full of energy and ideas. He is quick to try new things and generate plans. He was a scientist before stumbling into the jewelry world, so he approaches everything as an exercise in observations and experimentation. My mother is extremely grounded and keen to make sure that everything gets done correctly and on time. She has strong family roots in farming and brought her work ethic and commitment to people to the table.

Both my parents worked incredibly hard but did not start out with any business background. My father had to seek out training and education to that end as the company grew. Those resources fueled the first phase of growth at the company. Business is a constant stream of new challenges from there. We have built an incredible team at Halstead, so our success is a credit to the whole group, not just me and my parents. Every day the market is a little bit different than the day before. You have to pay attention, and you have to respond. A little bit of luck goes a long way as well.

Before devoting their attention exclusively to the distribution of jewelry supplies, your parents sold their own jewelry at craft fairs, one of the primary channels for selling studio work in the 1970s. How has that industry changed, in your eyes, over the years? Put differently, what skills does a young maker need to make a living today?

Hilary Halstead Scott: The company was built on the bead craze of the 70s but rapidly evolved into a more rounded resource for jewelry supplies, chain, and findings. The jewelry industry is fascinating and complex. It is full of different layers and segments that each have their own quirks.

We serve the small artist audience within the world of jewelry. This group made their living through craft fairs in the early years of the company, but that has definitely evolved over time. Artists had to adapt to the rise of the craft gallery model and then later the introduction of the Internet and sales platforms such as eBay and later Etsy. Artists struggled to make the online world work for them and experimented with direct sales and branding concepts. We are now watching the collapse of long-established sales channels as the supply chain from manufacturing to retail is reshaped into something new. That makes the market more difficult since small-scale artisans are competing more directly with mass manufacturers within the same sales channels. It is harder for consumers to navigate options and understand where their purchases ultimately come from.

This new landscape requires an unprecedented level of business smarts from young makers. That makes the skills promoted by the Halstead Grant and other entrepreneurial resources more critical than ever.

Particular emphasis on business accountability and promotional acumen is evident in the choice of your winners. The language in the grant presentation and application form is in fact very clear: You reward entrepreneurs as much as you do creative people. What made you decide to launch the grant, and why the emphasis on business?

Hilary Halstead Scott: We have served small jewelers for 43 years and we see our clients as partners. We are invested in their success. We celebrate their wins and we share in the crushing sadness of failure. Over the years, we watched many gifted makers close their doors and leave the jewelry trade. Over and over again, we saw that these struggles were rooted in a lack of access and/or commitment to sound business principles.

Making great work quite simply is not enough. Success in the world of independent jewelry studios requires two unique skill sets: one in design and craftsmanship and the other in strategic thinking and business execution. The Halstead Grant was launched based on my own experiences with business plan competitions in graduate business schools for my MBA and my master’s in international management. Writing a business plan is incredibly valuable for a start-up in order to establish clear goals and measurable steps toward self-sufficiency. We wanted to bring that concept to the jewelry community and give each new business an incentive to take time away from their bench to plot their course.

The grant also stipulates that the applicant must not have been in business for more than three years: One feels that you really want to give a leg up to designers at the very beginning of their career. Why do you think this is a particularly sensitive time in a business career?

Hilary Halstead Scott: Any small business can benefit from creating a business plan like this one. However, you can have the most impact by changing the thinking of emerging artists and making that business approach a part of their regimen from the start instead of just a one-time project. That is a powerful shift that can help to change an industry for the better. We want talented artists to thrive financially so they can have long, fulfilling careers in the arts. It is a tragedy when a gifted artisan leaves the field to seek more stable employment in another occupation.

One of our grant finalists this year wrote, “The process of writing the business plan has really put everything into perspective for me and I am excited for the future. I would have continued to put that off if it wasn’t for the Halstead application.” I’ve received dozens of emails like this over the years and it makes my heart soar. It affirms everything we hope to achieve with the program.

The grant panel consists in the three Halstead family members, a member of the Halstead marketing team, and one outside party from the industry. One would say this mirrors the “family-run” model. Have you ever been tempted to expand the jury to include more outside members?

Hilary Halstead Scott: Yes, but we face logistical barriers. Grant judging takes more than a month and a number of lengthy meetings, so it is not possible to do remotely. It is a tremendous commitment that is quite different compared to the standard half-day it takes to jury slides for a design competition. Due to the time involved and the need for participation in person, it does not make sense to have guest jurors come for the entire process.

However, we agree that it is important to bring in new insights now that we have established benchmarks for what the grant is all about. This year, we were excited to host our first guest judge for the final week of jurying. We were thrilled to have the perspectives of Cathleen McCarthy, an experienced jewelry industry journalist and founder of The Jewelry Loupe. Cathleen was gracious enough to travel to Arizona for a week to participate in our process. Her contribution was invaluable, and we look forward to including a guest judge each year as we move ahead. The short list for next year is really exciting and we hope to have a commitment nailed down soon.

Tell us about the selection process: How many applicants do you receive on average, and how do you winnow those applications down to five, then to one?

Hilary Halstead Scott: The application process itself winnows down the applicants. Over a hundred candidates begin the process each year, but it is extremely difficult. Any past applicant will tell you that the grant requires time, thought, and research. It is not a quick weekend project. In the end, we usually receive applications from about half of those who begin the process.

Judging happens in several stages. First, we read each complete submission packet and score both the business and jewelry collection on several criteria. The numeric scoring round allows us to make the first round of cuts. Next, judges are instructed to ignore the scores and conceptually group the remaining candidates into cohorts of similar applicants. These are roughly categorized as possible winners, possible finalists, and eliminations. The grouping step shakes out a second round of cuts. After the first two rounds we usually have the field narrowed down to about 15 in most years. This is the point where we have a guest juror join the process.

We then have a series of judging meetings where we discuss these candidates as a whole and their prospects for success given their plans and the current market climate. We compare the strengths and weaknesses of all of them and make a series of decisions that help the final rankings to take shape. It is rarely easy and we have to come to a consensus on all decisions. It requires that all the judges discuss observations and opinions with an open mind. The process works quite well for us and I think the results speak for themselves. Check out past winners and finalists; it’s an impressive group. You will probably see many names you recognize.

Winners get a cash prize (it has increased to $7,500, up from $5,000), a $1,000 voucher at Halstead, and, perhaps most importantly, feedback from the jury and a comprehensive promotional package (that includes press release guidance). Does that tend to translate into a longer working relationship? Do you follow the progress of the award recipients?

Hilary Halstead Scott: Absolutely. Another of our core principles at Halstead is that we think in decades. That extends to how we approach all of our relationships in business, including customers, employees, suppliers, and grant program candidates. I consider myself an advocate for the field overall and especially our past winners and finalists. I buy their work, I promote their work, I pitch them to contacts, and I involve them in industry projects wherever possible.

Most recently, Rebecca Rose, our 2013 winner, is creating the new signature trophy series for the grant program. Samantha Skelton, our 2015 winner, now juries the Halstead Design Challenge that we sponsor through the Society of North American Goldsmiths, along with me and Brigitte Martin. We have had several past winners and finalists visit us in Prescott, Arizona, to teach studio workshops to our staff. When I am at events, I try to host social gatherings with all the attending alumni of the program, including both winners and finalists. We are committed to supporting the long-term success of all of them. I love watching the arc of an amazing career. It is inspiring and it reminds me why I love my job.

From what backgrounds do the winners tend to come? What particular qualities do you think they have in common?

Hilary Halstead Scott: Many winners have a university metals education, but not all of them. Others have come through independent studio schools or apprenticeships. There are many paths to learn the craft. We promote the grant quite a bit through universities and SNAG, so we see a lot of applicants from those organizations.

We look for an identifiable signature aesthetic that can flex with trends and evolve with artistic development. That alone is a tall order. And that is the only part of applicants you can see as an outsider. As jurors, we also have a unique glimpse into their business plans, which gives us greater insight into behind-the-scenes facets of their studios. Winners know their market—and that extends way beyond the demographics of age and income. They have a clear understanding of their brand identity and the women who are attracted to their work. That allows them to develop marketing plans tailored to specific audiences. We also look for financial viability. Artists must think through the numbers of their price points, capacity, and demand to make sure everything adds up to revenue and a regular salary draw that will sustain them in their location. If your business plan has you earning below the poverty line, then there is a problem. Between the lines, we look for drive and hustle. It takes a certain kind of mindset to be a successful entrepreneur. You have to be disciplined and self-motivated to make it. That requires both passion and accountability.

You commented that SNAG was struggling (back in 2014) to “find its footing in a vast field of disparate interests spanning the spectrum between avant-garde art works and traditional bench jewelry.” What role do you think Halstead plays in that spectrum?

Hilary Halstead Scott: Halstead is rooted in sterling silver, so we cater to mid-market artisans in general. We try to give that segment a voice. Though I would not claim it is more or less deserving than other parts of the jewelry spectrum, they each have their place. High-end work and mass-produced brands naturally receive more national-level media attention due to budgets and the influence of fashion powerhouses. Yet there is great design work present in every segment of jewelry ranging through costume, bridge,[1] art, and fine categories.

Some people in the industry are dismissive of the efforts of others if they create work in lower price points or dare to create a production line. But designers have to be pragmatic about their businesses. You cannot earn a living selling one-of-a-kind $50 earrings; the numbers do not add up unless you approach design and production differently. The equation is entirely different when you are working on $20,000 bridal pieces. Jewelry is all about passion, craftsmanship, and fashion. But to feed those fires you have to approach your studio as a business, not just a hobby. You have to balance work that pays the bills with projects that spark your artistic side. That isn’t selling out. That’s called making a living. It is possible to make a good living in this trade with the right talents and education; but it may require you to rethink your approach.

You started the grant in 2006, and you are celebrating its 10th anniversary this year. What have been the grant’s most remarkable successes? Where do you want to take it next?

Hilary Halstead Scott: I am most proud of the success of our past winners and finalists. They have an amazing list of professional accomplishments. They have exceptional distribution partners and exhibitions on their resumes. Several have become wonderful parents while also building their companies, which is a success that deserves more recognition in the world. All but one of our winners are still full-time independent studio jewelers. After 10 years, that says a lot in this business, where so many people quickly come and go. Their work is very different one from another and so are their business strategies, but they are all still making great art as a career.

I think the grant itself has developed into a unique entity. It is very much a part of Halstead, but it also has its own identity and purpose. I am starting to visit studios and universities around the country to speak about the program and business planning in general. I hope that helps to augment the outstanding technical education that metals students receive with some business thinking that will help them to earn their living. My ultimate goal is to develop the grant into a full incubation residency program one day.

If you were to give one line of advice to a maker starting a studio practice, what would it be?

Hilary Halstead Scott: Making requires inspiration and courage. “Making it” requires business skills and a game plan. You can build both, just take one step at a time. The Halstead Grant program is a great place to start.

INDEX IMAGE: Hilary Halstead Scott, photo: Halstead/Jayme White

[1] “Bridge” used to refer to the area between costume jewelry and fine jewelry. For years, that was predominantly silver designs, whether they were one-of-a-kinds or production line pieces. The term “bridge” referred to the mid-level price points that retailers looked to fill between the more commonly defined categories of costume and fine. The term was used less as the art category arose and then other words such as “handmade” began to clutter the space. More recently, traditional segments are blurring as high-end silver work becomes priced near parity with some gold pieces and makers increasingly try to position silver as “fine jewelry.” Times change, and so does vocabulary.